An introduction to our special feature, Decolonizing European Memory Cultures.

An introduction to our special feature, Decolonizing European Memory Cultures.

Since 2020, the global Black Lives Matter movement has directed attention to the ubiquitous reminders of European colonialism in public spaces and institutions. Protesters toppled the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol and applied red paint to statues of King Leopold II across Belgium and of General Lyautey and Voltaire in Paris; others drew graffiti on statues of the Reich Chancellor Bismarck in Germany.[1] These actions drew connections between the racist violence to which people of color in Europe are subjected daily—many of them citizens of the different European countries in which they live, others migrants and refugees—and the longer histories of European colonialism. These histories are in many ways nationally distinct, but also part of a shared, virulent heritage across the continent, including in places that did not have colonies, or that were even themselves colonized as part of the Hapsburg, Ottoman, or Russian empires. The larger colonial histories that have now come more sharply into view struck many Europeans as new, because school curricula have until recently either ignored these histories or offered only self-flattering narratives of them.[2]

At the same time, academic specialists, artists, activists, and museum professionals have engaged for at least two decades in the project of “decolonizing” the memory cultures that shore up European identity. In this special feature, we approach “decolonizing European memory cultures” in two ways. First, we focus on the ways in which cultural institutions—especially museums—and practices have been fundamentally shaped by colonial and neocolonial relations in ways that have become naturalized and unremarkable, and thus difficult to see. Second, we understand the decolonizing of European memory cultures as the steps necessary to painstakingly undo the institutional protocols in which racialized inequality and hierarchical relations with the Global South are inscribed. The focus on cultural institutions requires consciousness-raising, to which scholars and artists can contribute. Indeed, scholars can promote new understandings of these unequal relations through historical research, while artists tap into different ways of knowing and working beyond the limits of what the historical archive yields. The strategies used in this decolonizing refers to material transformations as the implications of this consciousness-raising are drawn out and changes are implemented. Moreover, other professionals in the cultural sector, as well as legal professionals, also partake in the decolonizing of memory cultures, as they work toward altering institutional protocols, policies, and laws.

A growing body of scholarship over the last fifteen to twenty years has explored and detailed both the ideological and material aspects of decolonizing European memory culture.[3] A substantial number of these studies have been concerned with the large ethnology (now called “world culture”) museums that first positioned themselves consciously as postcolonial. Indeed, these museums have sought to shed the colonialist associations embedded in their histories and collections. For example, the Musée du Quai Branly opened in Paris in 2006 as an alternative to the Musée de l’Homme; the Royal Museum of Central Africa was revamped as the AfricaMuseum in 2018 in Tervuren, Belgium; the Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration in Paris opened in 2007 in one of the former sites of the 1931 Colonial Exposition; the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool also opened in 2007; and the Humboldt Forum in Berlin opened in 2020.[4] Other recent developments such as the comprehensive report commissioned by President Emmanuel Macron in France on “The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics” (2018) and the 2022 agreement by the German government to restitute many of the Benin Bronzes held in German museums are among the many actions animating public debates in various countries about what it means to decolonize European cultures. These actions appear to reverse the truculent stance adopted by self-proclaimed “universal museums” in their notorious “Statement on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums” (2004) and tracked over several decades by Bénédicte Savoy in Africa’s Struggle for its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat (2022). However, this stance has begun to crumble. Its erosion has been hastened by activists’ and artists’ interventions that have framed purportedly benign, colonial-era acquisitions as looting.

This special feature delves into the different ways in which “artivists” have attempted to decolonize the memory cultures of Europe. Cresa Pugh contributes to the debate by framing restitution as “unlooting.” Her essay about a rogue performance artist reveals the wavering line between the language of law—according to which colonial looting was legal but present-day unlooting is a crime—and a decolonial ethics legible in the public performance of theft. Several other contributions in this feature likewise highlight the work of artist-activists, whose “intrusions” and interventions in museums, archives, and sites of memory have triggered a fruitful transnational debate. This feature also sheds light on the regional specificity of decolonizing endeavors on the European continent, revealing some of the differences between Western and Eastern Europe and highlighting the voices of artists and academics of color in the decolonizing debate. Importantly, the feature brings into dialogue the perspectives of academics, practitioners, curators, and artists, who all bring distinct forms of expertise to the project of activating colonial pasts for contemporary antiracist commitments.

Archival intruders

While art museums have become objects of decolonizing inquiry by numerous scholars and activists, the significant impact that artists have made as interlocutors of museums and other cultural institutions remains underresearched. As Katrin Sieg has shown in Decolonizing German and European History at the Museum (2021) and as we illustrate here, artists sometimes act as hostile intruders but are also often included as partners in museum’s decolonizing endeavors.[5] Likewise, in this feature, we have invited a number of artists to share their thoughts and work.

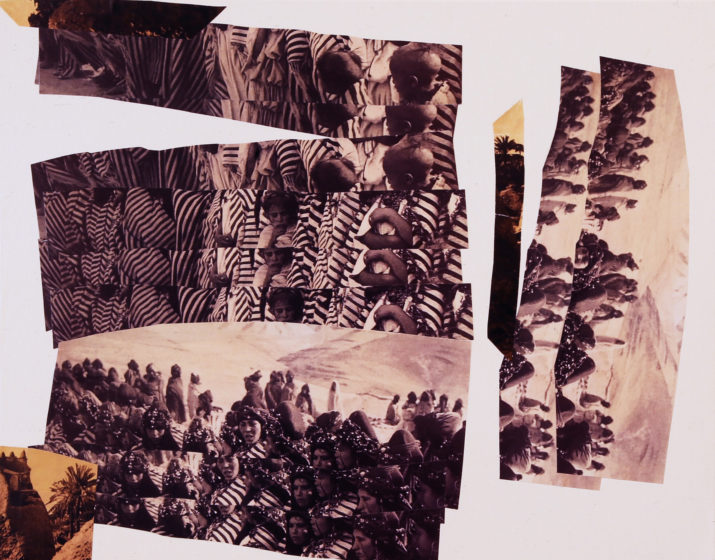

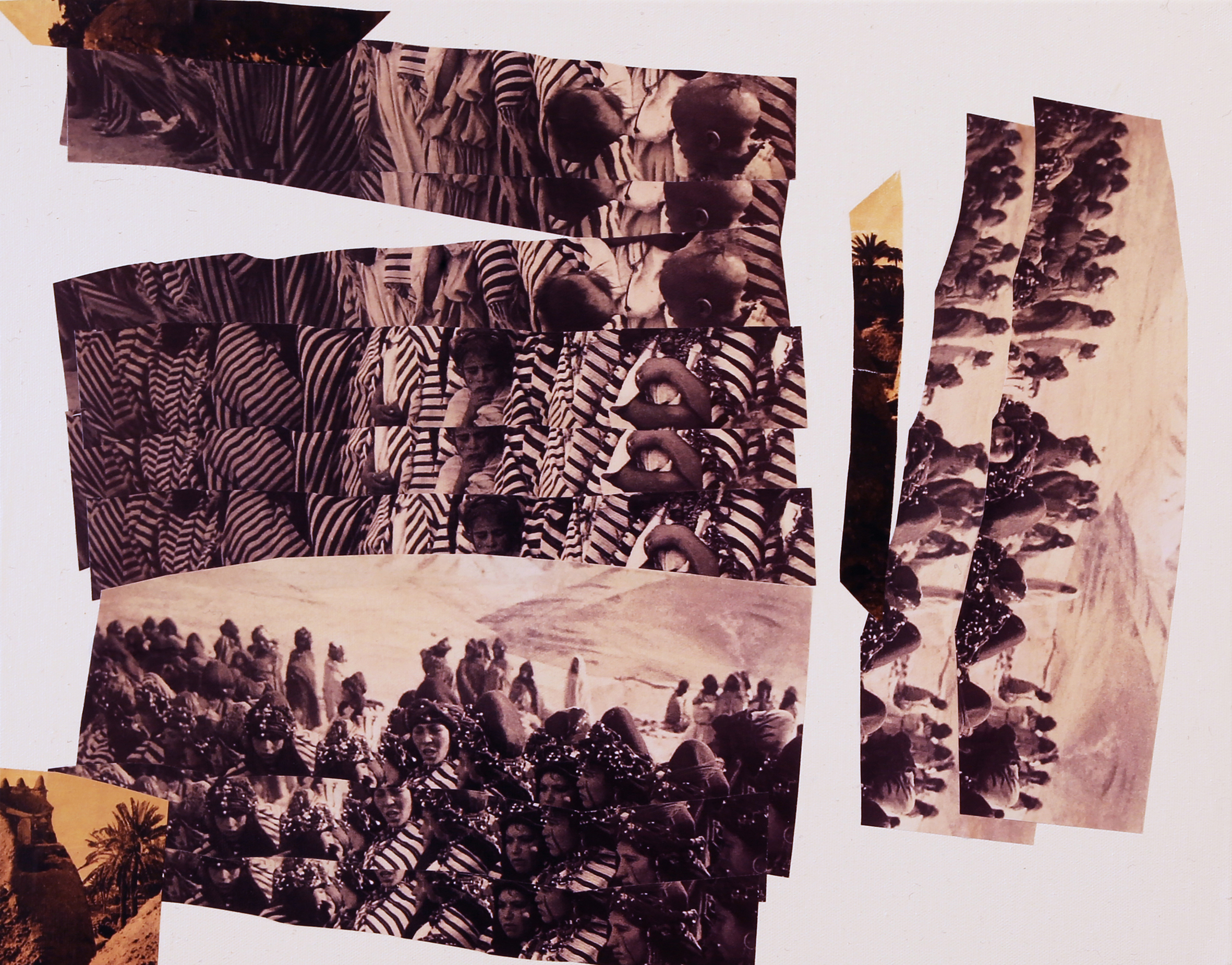

The visual exhibit associated with the feature presents two artists who have tackled the topic of decolonization in their work through the re-use and alteration of “anthropological” photographs. These images highlight a history of oppression and the essentialist gaze once directed at colonial subjects—whether these subjects were located within Europe or without. Tomas Colbengtson, a Saami activist-artist, uses archival images to cast light on the annihilation of the Saami people and their cultural practices by superimposing images in which landscapes and individuals take on an ethereal presence and the land plays a key role. Drawing on the mineral qualities of glass, he often positions these images in situ, on the land from which the Saami were displaced. Colbengtson’s work conveys a palpable history of loss (of livelihoods, culture, language, and religion) and pain that has endured to the present, although glimpses of hope emerge. To contextualize Saamiland, Alexandra Birch helps historically situate the Saami experience as a twice colonized northern European Indigenous people whose cultural spaces have been confiscated, coopted, expropriated, and contaminated. The second artist in our visual exhibit is Amina Zoubir, who also used photographs. Zoubir is an artist, filmmaker, and video art curator based in Paris and Algiers, whose works have entered the permanent collection of the Museum of African Art (MAU) in Belgrade, Serbia. Her montages both expose and exorcize archival images. Her approach is characterized by an iconoclastic impulse that aims to destroy or deconstruct the colonial visual archive.

The projects of the artists writing about their work in this special feature go beyond iconoclasm and experiment instead with methods of what Saidiya Hartmann calls “critical fabulation.”[6] The performances devised by Laura Frey and Vincent Bababoutilabo and Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński are firmly centered in the perspectives of Black Europeans and colonial migrants. Their audio and visual works are based in rich and rigorous archival research, but they dance at the limit of the archive: they refuse to be reduced to it while also not quite venturing into pure fabrication. Historian Laura Frey and theater artist Vincent Bababoutilabo, both based in Berlin, collaborated on two web-based projects that delve into Berlin’s Black history. The artists collaborated with the local museum to research the lives of colonial migrants and produced an audioguide and a visual, web-based project accessible to visitors. These audio-visual materials help viewers turn their stroll through a park where a colonial exhibition took place in 1896 into an encounter with colonial history and trigger a reflection on today’s Black Berlin. Frey and Bababoutilabo’s work illustrates how artists can benefit from the access to museum archives, but the team’s “critical fabulation” also exists in productive tension to the museum’s documentary approach.

Similarly, our interview with Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński, a Vienna-based artist, highlights how she makes an important contribution to decolonizing exhibitionary formats through her video installations A Letter (2019) and Fleshbacks (2021). The former is inspired by a remarkable letter written in Ga by a performer in an ethnological display (today often referred to as a “human zoo”) and published in a Viennese newspaper.[7] The letter, which indicts such displays, constitutes one of the few documents expressing a performer’s perspective on this widespread practice, which brought foreign people into close, often titillating, proximity with European visitors, while inserting maximum cultural distance and hierarchy between subjects and objects of the gaze. Through her video installation, Kazeem-Kamiński wrestles with the question of scant and hostile colonial-era archives and meditates on how these archives can provide comfort and courage to contemporary Black artists based in Austria. Like Frey and Bababoutilabo, Kazeem-Kamiński mines the archive to assemble genealogies of Black resistance, succor, and joy.

Our second interview underlines how decolonizing the museum also relies on collaborative projects bringing together local communities, academics, and museum curators across borders. In explaining her work as associate curator of the recent exhibition “Black Indians of New Orleans” at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, Kim Vaz-Deville reveals how these kinds of projects are generated and what their intended and potential outcomes are. Vaz-Deville shows how the little-known history of the Mardi Gras Black masking Indians and the figure of the Big Chief transcend the context of New Orleans to serve as a rich cultural and mnemonic bridge between Africa, Louisiana, and the European history of slavery in the Americas. Indeed, the exhibition highlights the connection between slave ports in Louisiana and European cities, which relied on the trade for their development in the eighteenth century and have only timidly started to publicly interrogate their role in the transatlantic slave trade. For example, in Bordeaux, the third largest slave port in France and departure point for 508 slave ships, the Musée d’Aquitaine inaugurated two permanent exhibitions in 2009 to relate the city’s role in the slave trade; moreover, a statue of Modeste Testas (1765-1870), an enslaved woman from East Africa, was unveiled, facing the river, in 2019.

We include here excerpts from two works of fiction recently made available to Anglophone audiences. Sharon Dodua Otoo’s first novel, Ada’s Realm (translated from the German in 2022), is grounded in the braided histories of European colonialism, racism, antisemitism, and misogyny, but invents new literary forms of transhuman, transhistorical storytelling to imagine antiracist, Afrofuturist possibilities. Otoo is a prominent Black British author, editor, activist, and public intellectual who lives in Berlin, writes in German, and received the prestigious Ingeborg Bachmann prize in 2016. Ada’s Realm has already garnered considerable critical acclaim.[8] The excerpt we selected is part of the chapter that narrates the theft of a golden bracelet with which Ada, a bereaved mother on Africa’s Gold Coast in the fifteenth century, had adorned her dead baby’s body. The bracelet is stolen by a Portuguese merchant named Senhor Guilherme. Throughout the book, Ada, Guilherme, and the bracelet reappear in different constellations over the ensuing five centuries up to the present, repeating and varying situations of colonial, racialized, and misogynist violence. Only in the present does Ada, now a Black British computer programmer looking for a home for herself and her unborn child in Berlin, appear able to navigate the violent histories she has inherited with a degree of Afrofuturist hope. At the end of the novel, Ada encounters the gold bracelet in a German museum exhibition catalogue and debates with two old Afro-German women whether to request its restitution, only to dismiss the idea. Their decision reflects the misgivings of decolonial intellectuals who, like Achille Mbembe, fear that restitution will close rather than open up the debate about what obligations arise from colonial extractionism.[9]

The second literary excerpt, recently translated from the Sesotho, was written in 1962 under the title Pelong ya Ka by Sophonia Machabe Mofokeng, an influential South African thinker who has often been relegated to the role of a mere local anticolonial essayist writing in a minor African language. In fact, his novel here provides illuminating glimpses into the knowledge realms and social relations of the colonized. In the excerpt, what comes through is a critique of the European notion of “border” and the idea of mobility, which also resonates with Tomas Colbengtson’s work. The book’s publisher, Seagull Press, initially founded in India by a theater practitioner, has been instrumental in the ongoing effort to widen the scope of literary and theoretical production to include “postcolonial” voices and decenter the humanities. In their introduction to the book, series editors Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Hosam Aboul-Ela describe their mission as advocating for “the scandalous notion that the literary figure of the Global South is as human as the European, complex, subject to the dynamism of history, fluid, unrepresentable, and impossible either to essentialize or reduce to any glib counter essentialism.” The main goal of the series has been to translate theoretical approaches outside the Anglo-American and European metropolitan spheres, to offer readers texts emanating from various (often postcolonial) literary cultures and spaces to “point out how each is singular in the philosophical sense, namely, universalizable, though never universal.”

Situated decolonizations

Kazeem-Kamiński’s engagement with fin-de-siècle Viennese culture raises the question of how European countries or regions that did not engage in overseas colonization, such as the Habsburg empire, should position themselves vis-à-vis the discourse of decolonization. This question is taken up in Marie-Laure Allain Bonilla’s article on decolonizing art museums in Switzerland, a country where the lack of state involvement in colonial ventures was long taken to mean that decolonizing efforts do not apply. And yet, as Allain Bonilla mentions, not only have scholars long identified the historical participation of Swiss missionaries and merchants in colonial endeavors, but Swiss banks and corporations have actively pursued neocolonial extractivism, to which public art museums have in turn contributed by providing an ideological foundation promoting a Eurocentric, white-supremacist construction of the canon. Allain Bonilla shows that the struggles to decolonize Swiss art museums have been ongoing and have involved a range of actors. Further, former socialist and non-aligned countries in east-central and southeastern Europe have complicated relationships to colonizing projects and to decolonization, which are mapped by three contributions to this issue. Political elites in these countries share Switzerland’s defensive stance that the absence of state-sponsored colonialism in the past exempts them from decolonizing efforts in the present; in addition, eastern European countries were themselves colonized and, during the Soviet era, subscribed to anticolonial ideologies and solidarity with the “Third World.” These articles grapple with colonial afterlives in European countries that were not colonial metropoles and the need to think about decolonization as a geographically and ideologically specific, i.e. situated, endeavor.

Eastern Europe, comprising the East-Central European (ECE) region, is the focus of Erica Lehrer and Joanna Wawrzyniak’s essay, and Yugoslavia (now ex-Yugoslavia) is the subject of contributions by Ana Sladojević and Emilia Epštajn. This region encompasses territories historically ruled by the Habsburg, Ottoman, and Russian empires that are located in the historic “bloodlands,” where German and Soviet empires violently clashed in the twentieth century.[10] Moreover, serfdom—sometimes compared to plantation slavery—endured longer there that in the western part of the continent. Erica Lehrer and Joanna Wawrzyniak explore what this complex situation portends for the task of decolonizing museums in the East-Central European (ECE) region, while Ana Sladojević grapples with anticolonial museology at the Museum of African Art (MAU) founded in the ex-Yugoslavia in 1977. Lehrer and Wawrzyniak ask what it means to describe this region as shaped by “colonial violence.” To complicate matters, ECE countries, as part of the erstwhile socialist world, subscribed to official anticolonialism and practiced anticolonial solidarities with African liberation struggles. How does this complicated history shape notions of race? How to account for the fact that stridently anticolonial rhetorics are now often harnessed by elites in this region for right-wing nationalist causes and sometimes wielded against the EU? Lehrer and Wawrzyniak explore what this complex situation portends for the task of decolonizing museums in the East-Central European region, while Ana Sladojević grapples with the anticolonial museology at the Museum of African Art (MAU) founded in Yugoslavia in 1977. That museology was inspired by Yugoslavia’s non-aligned status and foreign policy. Sladojević reflects on the conditions for reconnecting the decolonizing discourses with which museums in the region have been concerned since the 2010s to the historic anticolonialism embodied by the MAU. She argues that this past might offer a foothold for decolonizing projects that cannot be imported wholesale but must be carefully situated in regional and institutional histories. Emilia Epštajn complements Sladojević’s article by reporting on an international conference that was hosted at the MAU in 2022 on the theme of “An Anticolonial Museum.” The conference conveyed the impressive diversity of actors engaged in bringing anticolonial and decolonial approaches together in provocative and playful ways.

The contributions by artists, academics, activists and curators in this feature reveal the decolonization of European memory cultures as a situated, geographically specific process. The work of literary, visual, and performance artists underscores the need to listen and look beyond the violent material collected in colonial archives to imagine antiracist futures for Europe. While our feature cannot offer an exhaustive picture of the field, we are thrilled to contribute to a growing area of politically engaged art and scholarship. The decolonizing initiatives included here spotlight some of the exciting work on European memory cultures undertaken across the continent. Future research will hopefully direct more attention to memorials, which have been so central to the recent wave of colonial memory and antiracism activism in the public sphere. Moreover, we see an urgent need for future research that reflects the full regional diversity of decolonizing endeavors in Europe. We hope that the present feature will inspire readers to confront the afterlives of colonialism, along with Europe’s anticolonial and antiracist histories, and to investigate other regions, other media, and other political movements and activist spaces. Finally, we would like to thank Maureen Porter (University of Pittsburgh), who helped to conceptualize this issue, even though life intervened and prevented her from participating as co-editor of this issue.

Research

- “Cocoa Beans Do Not Grow in the Swiss Mountains: Swiss Museums of Modern and Contemporary Art and the Winds of Decolonial Change” by Marie-Laure Allain Bonilla

- “‘Bandits Into Militants’: Unlooting and the Legitimacy of Plundered Cultural Heritage Removal” by Cresa Pugh

- “Remembering Early Twentieth-Century Colonial Migrants in Berlin through Performance” by Laura Frey, Vincent Bababoutilabo, and Joel Vogel

- “An Anticolonial Museum” by Ana Sladojević

- “This is Saamiland: An Alternative History of Solovki and the White Sea” by Alexandra Birch

Commentary

- “Decolonial Museology in East-Central Europe: A Preliminary To-Do List” by Erica Lehrer and Joanna Wawrzyniak

- “Conference Dispatch: An Anticolonial Museum” by Emilia Epštajn

Visual Art

Fiction

- In my Heart by Sophonia Machabe Mofokeng, translated from the Sesotho by Nhlanhla Maake

- Ada’s Realm by Sharon Dodua Otoo, translated from the German by Jon Cho-Polizzi

Interviews

- “Haunting Austrian Archives of Race through Black Feminist Art and Performance: An Interview with Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński” by Katrin Sieg

- “Black Maskers of New Orleans in Paris: An Interview with Kim Vaz-Deville” by Hélène B. Ducros

Book Reviews

- British Muslim Women in the Cultural and Creative Industries, reviewed by Mary Vogl

- Performing New German Realities: Turkish-German Scripts of Postmigration, reviewed by Azadeh Sharifi

Campus

Campus Round-Up

Katrin Sieg is Graf Goltz Professor and Director of the BMW Center for German and European Studies at Georgetown University. Her research sits at the intersection of critical race studies, performance and museum studies, and postwar European culture. She is the author of four monographs, most recently Decolonizing German and European History at the Museum (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021).

Hélène B. Ducros, JD, PhD, is a human geographer whose research has focused on place-making through heritage-making, landscapes of remembrance and commemoration, and the circulation of cultural models of heritage preservation. Her latest publication is Justice in Climate Action Planning (co-edited with Brian Petersen, Springer Nature, 2022).

[1] For more on this topic, see, for example, Les statues de la discorde, by Jacqueline Lalouette (Editions Passés Composés, 2021).

[2] For Belgium, see Geert Castryck, “Whose History is History: Singularities and Dualities of the Public Debate on Belgian Colonialism” Europe and the World in European Historiography, ed. Csaba Lévai (Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2006) 71—88. For Germany, see Florian Helfert, “(Post-)colonial Myths in German History Textbooks, 1989-2015,” German Politics and Society 39:1 (March 2021) 79—99.

[3] Here only a selection of German sources: Hannimari Jokinen, Flower Manase, Joachim Zeller, eds., Stand und Fall: Das Wissmann-Denkmal zwischen kolonialer Weihestätte und postkolonialer Dekonstruktion (Berlin: Metropol, 2022); Ulrich von der Heyden, Joachim Zeller, Kolonialismus hierzulande: Eine Spurensuche in Deutschland (Erfurt: Sutton, 2008); Joachim Zeller, Kolonialdenkmäler und Geschichtsbewusstsein: Eine Untersuchung der kolonialdeutschen Erinnerungskultur (Frankfurt: Verlag für Interkulturelle Kommunikation, 2000); Manuela Bauche, “Postkolonialer Aktivismus und die Erinnerung an den deutschen Kolonialismus,” Phase 2: Zeitschrift gegen die Realität 37 (2010) np.

[4] See for instance the anthologies published by the EU-funded research cluster Museums in the Age of Migration (MELA), publicly accessible at https://www.mela-project.polimi.it/index.htm; about the Musée du Quai Branly, see Sally Price, Paris Primitive: Jacques Chirac’s Museum on the Quai Branly (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007; about the Royal Museum of Central Africa/AfricaMuseum: Véronique Bragard, “’Indépendance!’: The Belgo-Congolese Dispute in the Tervuren Museum,” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 9:4 (Fall 2011), 93—104; about the International Slavery Museum, Liverpool: Silke Arnold-de Simine, Mediating Memory in the Museum: Trauma, Empathy, Nostalgia (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013); about the Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris: Sonia Labadi, Museums, Immigrants, and Social Justice (London: Routledge 2018); about the Ethnology Museum Berlin/Humboldt Forum: Friedrich von Bose, Das Humboldt-Forum: Eine Ethnographie seiner Planung (Berlin: Kadmos, 2016

[5] Katrin Sieg, “Artists in/against the Archive,” Decolonizing German and European History at the Museum (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021) Françoise Vergès, “The Slave at the Louvre: An Invisible Humanity,” Journal of Contemporary African Art 38-39 (November 2016): 8-13; David Joselit, Heritage and Debt; Carol Duncan, “Art Museums and the Ritual of Citizenship,” Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Display, eds., Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine (Washington: Smithsonian Books, 1991) 88-103; Alice Procter, The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story of the Art in Our Museums and Why We Need to Talk About it (London: Cassell, 2021).

[6] Saidiya Hartmann, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe Number 26 (Volume 12, Number 2), June 2008, 1-14.

[7] The term was popularized through the exhibition (later a documentary) Human Zoo: The Invention of the Savage (2011) at the Musée du Quai Branly, curated by Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boetsch, and Nanette Snoep.

[8] Sarah Colvin, “Freedom Time: Temporal Insurrections in Olivia Wenzel’s 1000 Serpentinen Angst and Sharon Dodua Otoo’s Adas Raum,” German Life and Letters 75:1 (January 2022): 138-165; Jolanta Pacyniak, “Things travelling through time and space: The role of it-narratives in Sharon Dodua Otoo’s novel Adas Raum,” Acta Germanica 50:21 (December 2022) 117-125.

[9] Achille Mbembe, “The Truth is that Europe took things from us that it will never give back,” Le Monde (December 1, 2018)

[10] Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin (Basic Books, 2012).

Image from the Archaeology of the colonized body series: Mamounia. Collages on canvas, from the photographic collection of the Markk Museum Hamburg, 2021. © Amina Zoubir, ADAGP.

Published on February 21, 2023.