This is part of our special feature, Decolonizing European Memory Cultures.

Translated from the German by Jon Cho-Polizzi.

Among the Toothless

Totope, March 1459

No matter how tightly Mami Ashitey held me in her hand, no matter how quickly she swung her arm or how often she spun me about, she did not succeed in hurting Ada with her blows. Which, of course, gave me a certain pleasure.

In 1459, I was – as yet – unable to choose which object I would become, but as a brushwood broom, I still possessed a bit of leeway. At that time, at that place, my role was utterly uncomplicated. Most of the time, I lay about outside in a shady corner beside four or five clay pots and several piles of charcoal. I was put to use at least several times per day, but the space between the three small houses on the property was quite manageable. Even those who made the utmost effort to shirk from further household chores could sweep the dust, the chicken shit, and the fish scales together and haul them to the waste heap in no more than the span of two work songs. Naa Lamiley usually managed it in only a few breaths. And since it was typically her task to keep things clean around the yard, I had a lot of time on my twigs.

It was in just such a quiet hour, as I lay sun-drunk and dreaming, that Mami Ashitey put me to use. She swept and laughed and swept-laughed more, and I suspected no ill will. I remember that my twigs were all quite stiff and orderly – this was something in which I took particular pride. The toothless ones liked to tell one another that I looked so good because I was made of palm fronds while all the other brooms had been made of coconut leaves. And until that morning, I had had no cause to convince the women of anything to the contrary.

Mami Ashitey paused. I noticed that she was growing angry, as her grip around me tightened. A low rumble issued from her lips. And in the next moment, I flew through the air towards Ada’s shoulder.

“What is wrong with you?!” I heard Mami Ashitey cry. Her eyes squinting as her mouth twisted in rage.

“For! The! Last! Time! Use! The! Right!” Each word was emphasised with another whack.

Naa Odarkor nodded to her wife, her otherwise placid forehead distorted by her narrowed brow. Although she was typically considered the more lenient of the two, it had grown customary for even Naa Odarkor to smack Ada on the upper arm with her stick rather than remind her at every opportunity – whether eating, cooking, or in greeting– to use only her right hand.

“Be quiet!” she would threaten. “Otherwise, I’ll give you a real reason to cry, o!”

The women of Totope treated Ada as though she had emerged from Mami Ashitey’s own loins. In their eyes, her daily floggings were glowing proof of familiarity and love.

I was not pleased to be misused for such purposes, and so I always slowed my flight just before I was to strike Ada. And while Mami Ashitey continued demonstrating her love for Ada with ever-growing eloquence, a stranger was approaching the compound.

* * * * *

Guilherme Fernandes Zarco, an ill-tempered (and now for more than two years, insolvent) Portuguese merchant, had clambered down that very morning from the deck of the São Cristóvão and swum with great effort to the mainland. (How I knew of this, I will explain to you all in good time. I beg for your patience here: But let’s stay with Guilherme for the moment.) As he stood upon the edge of the sea and glanced back at his ship, it seemed as though the freshly mended topsail rose directly from the depths of the blue water. Except for the fluttering sails, there was nothing but a great emptiness, a rustling and swirling, a spiral of blue and dazzling green, and sunlight gleaming like scattered diamonds on the surface of the waves. An endless shhhhh. . . it could all have seemed so peaceful – but for his suffering.

A few short days earlier, Guilherme had gambled away his every possession – lost everything but the clothes upon his back and the black sword at his side. He had tinkered his last shirt into a poor excuse for a sunhat to shield his bald head, his ears and even the tip of his disproportionally long nose. Everything else – especially his shoulders, chest, underarms and legs – had been surrendered to the merciless heat. As the São Cristóvão had approached the Costa do Ouro, his skin had smouldered as if in warning to the other so-called explorers: “Do not tarry here on pain of death!”

Guilherme’s every unnecessary movement resulted in a harsh punishment for whomsoever caused it, or if the culprit were not at hand, for whomever came within his reach. He had become a wandering pillar of pain, and why oh why oh why had he not remained lying aboard the ship? Why had he agreed in the first place to embark upon this journey? Africa? A second voyage? He gnashed his teeth as he thought about his creditors. Guilherme suppressed all too gladly any reminder that he had been forced back upon the high seas to escape his many debts.

The village in which Ada lived lay less than half an hour by foot through the rainforest from the coast. Of course, Guilherme could not have known this. But he supposed that the people who had laid their fishing nets upon the beach could not live far away. He kneeled down and rubbed one corner of a net between his fingers. It was stiff and warm, and obviously well maintained. Here and there, a few patches glittered a vigorous green from freshly woven strips of tree fibre. But where were their boats? He shielded his eyes and frowned. There was nothing to be seen to his left; to his right, only a single, sun-bleached canoe. From a distance it looked like nothing more than an odd piece of firewood.

Guilherme would have preferred to leave for the settlement at once. He was not sure how long it would take for his remaining colleagues – at least those who still had the strength to swim ashore – to reach the beach. Their heads bobbed up and down on the surface of the water, their arms straining against the distance. And where was Afonso? Had he leaped from the São Cristóvão at all? As soon as he had identified the tiny figure among the struggling swimmers, Guilherme turned away from the commotion, stabbing with his sword into the sand. If they were all so useless as to drown immediately, he at least did not wish to observe the spectacle.

But there was no reason for Guilherme to maintain such thoughts. The sailors were all especially motivated – believing, as they did, that their mission was all but complete. They had set out in search of a certain Mansa Uli II and were of the opinion they were mere hours from their goal. Early that morning they had all already congratulated one another on their success. Everyone but Guilherme. He had folded his arms across his chest and scowled tight-lipped at his comrades – the paupers could not be dissuaded from this abstruse idea.

Their obsession was the direct result of the persuasive power of Diogo Gomes de Sintra, “Navigator, Explorer and Writer”. This recently disgraced customs official had convinced them all to come along on the journey to Africa in the first place, promising that they would return with unimaginable quantities of gold. His claim – that this Mansa ruled over the entire continent – was an inauspicious embellishment of an otherwise carefully constructed lie which danced along in parallel to the truth of things. According to Gomes, Mansa Uli II was nearly as fabulously wealthy as the esteemed Mansa Musa, well known to be the richest person of all time.

And so, the men who were now labouring to drag themselves one by one onto the beach could not be convinced otherwise that – even if Africa were, in fact, simply one kingdom – its king would not necessarily condescend to trade with a simple captain like Gomes. And even if this could, against all odds, be achieved – for after all, nothing is quite so consistent as constant change – it remained unthinkable that this Mansa would be found on a measly island or an impoverished coastal strip on the far margins of his empire.

Months later, Gomes would grind his teeth in recognition that Guilherme had been right. Years later, in the closing hours of his life, Gomes would cast the entirety of his career as an explorer in a favourable light in his memoirs. And decades after that, it would be forgotten entirely that Diogo Gomes de Sintra, “Navigator, Explorer and Writer”, would never have given up his search along the coast and set out on his march into the interior of the continent, had it not been for Guilherme and his distinctive obstinacy.

Nevertheless, the incorrigible captain had cried “Lançar âncora!” on that fateful morning. And so they had dropped anchor a third time, at random, in the Gulf of Guinea.

The first sailor reached land as Guilherme’s sword gleamed dry as a bone. But it still took several more minutes before all the men had assembled before him – Afonso hung back at the rear of the group. Only then was it conveyed to Guilherme that Gomes, due to “health complications”, had remained onboard the ship. Guilherme suppressed a disparaging snort, for it was no secret that Gomes – in frustration – had emptied the final keg of wine during the night.

Guilherme did an about turn and began his march. He carried himself as though he were the rightful owner ofthe entire land. The remaining sailors, all on the continent for the first time, struggled to keep up with his unyielding pace. They would first need to acquire something of his conduct: He soon left them behind, and that was fine with him. Guilherme slogged his way alone through the humming underbrush. Battered shrubs and mangled trees crashed to the earth behind him. Distraught parrots lamented in shrill tones as they took shelter in the crowns of neighbouring trees.

When he reached the dusty path which led from the jungle to the village, Guilherme’s laboured breathing calmed. Pearls of sweat cooled his brow and glittered on his chest. He had left the others far in his wake, and he could no longer hear their voices. He continued along in the direction of the settlement and remained standing when he reached the edge of the first plot. He watched as Mami Ashitey punished Ada with the help of the broom. He shaded his eyes with his right hand, grateful for the distraction – the screeching and chattering. His gaze swept over the oddly familiar terrain.

Three tiny houses arranged about a round plot of land. Rounded cob walls, garments spread out to dry on the thatched roofs, and a freshly swept courtyard. The light – peaceful and clear – was unperturbed by the wisps of smoke rising from the coal stove. Strains of sound, rhythmic and shrill; a quiet breeze which caressed and embraced Guilherme where he stood. And untold quantities of fish. Smoked herring, dried sardines and fried shrimp: gleaming and aromatic, ready for the market stands.

He had only wanted to whisper “articulately”, but as he turned, seeking, at the very least, for Afonso, he found himself unable to keep his voice under control. He felt the hunger in his belly all too persistently, was too tormented by the waves of heat upon his face; it had been much too long since he had issued a command in anything resembling a normal tone of voice: “AFOONSOOO!” he cried.

About time! I thought. It was important that Ada and Guilherme met before the storm broke.

And so, the toothless ones became aware of his presence. They stared at Guilherme with huge eyes and open mouths. Mami Ashitey held me in mid-swing, high above her head, her gaze fixed upon the white man. Ada fell silent.

Guilherme removed his provisional headdress and glanced down at the dirt. In doing so, he caught a glimpse of the beads on the bracelet Ada still held in her hand. Perfect, I thought. Now it shall begin at last! The golden hue of the beads did not shine with their usual splendour and pretence: They glowed, rather, with the humility of moonlight. Guilherme had never seen such quality, not even in the mines of Obuasi. He took a step forward.

“Eh-eh!”

He understood nothing else.

Mami Ashitey raised her eyebrows.

This he understood at once.

Guilherme glanced about himself once more to be certain that his boys had not yet caught up with him – of course not, where were they anyhow? – then he began. Somewhat half-heartedly, he pointed with his right index finger at his chest:

“Guilherme Fernandes Zarco.”

Nothing happened. He coughed. Still nothing. He pointed to himself once more:

“Eu – Guilherme Fernandes Zarco – GIL-YER-ME.”

The jaw muscles of the toothless ones moved up and down; Naa Odarkor, squatting beside the fish, clutched her knife more tightly in her fist. Guilherme exhaled through pursed lips. Although this was certainly not the first time that men like himself had come ashore on the Costa do Ouro, these women still had not learned to speak properly.

As Guilherme drew his breath to begin anew, a flood of sounds streamed forth from Mami Ashitey. She gesticulated, rhythmic and frantic, as if to ask him why he had not brought someone with him who had mastered both his own vernacular, as well as hers. He had decided, at least, to interpret her many hand and finger movements so.

Guilherme sought after Afonso one final time in vain. (But actually, it was not ordained for him to appear on this page of the book.) Guilherme’s movements pleased Mami Ashitey even less than before. Her tone became more forceful, the individual syllables shot forth staccato from her mouth. The other toothless ones agreed. Guilherme’s gaze swept from one elder to the next. He watched as their thin eyebrows danced up and down across their foreheads, how their grey heads turned to and fro, their fine lips barely keeping time with the unrelenting pace of their words. Most of all, he observed that they were not truly angry, but seemed, rather, motivated by some exaggerated anxiety. Some kind of threat.

The baby, now uncovered, was attracting all manner of flies which danced around his nose. Mami Ashitey struck Ada one final blow to bring the matter to a decisive end, and placed me back in my corner. Ada rubbed her head discreetly as Mami Ashitey bent over the body, swatting at flies and reaching for the white cloth once again.

It was shaken vigorously, this cloth. And he was inspected thoroughly, this Guilherme. A wad of spit flew conspicuously from her mouth and landed a few inches from his feet. It frothed boldly on the red dirt floor before disappearing, bubble by bubble, in the dust. Guilherme acted as though he had not noticed. However, the baby’s corpse received a bit of the spit as well. Mami Ashitey bent down once more, this time to envelop Ada’s child in the cloth. As she rose, Guilherme saw tears in her eyes. At first, they were only a few drops which vanished swiftly against the heat of the ground. Or perhaps he was mistaken? The heavy sky seemed poised to release an impressive display, of this he could be certain. Behind the delicate blue, coal-black strands of gossamer were gathering.

And then the rain broke loose with such fury that Guilherme could hardly make out his own outstretched hand. Water ran frantic red around the coal stove, between the stones, over the ants, pooling in puddles. He had not caught the swift transition from a reluctant “What was that?” to a rash “Let’s go, o!” The hens, the goats, the lizards had all vanished in an instant. The toothless ones had made their way at once into the shelter of one of the small houses, salvaging nearly all the food along the way – a single fish head failed to make the exodus from the courtyard to the cover of the buildings and sulked alone, forgotten in the mud.

Ada had not stirred from her seat. The storm rain pelted against her eyes, her chin, her cheeks, but she remained seated next to her son. Soon he will be completely free, she thought. The beads of her bracelet would protect him on his final journey. Yet she laboured to tie it around him, the cloth clinging to his body like a second skin. And as Guilherme – hope in his heart – signalled to her with a few hand gestures that he could lift the child in order to ease her task, she nodded. And as Guilherme – corpse in his arms – signalled to her with a few movements of his head and shoulders that he knew a good final resting place, she nodded again, grateful that Ataa Naa Nyɔŋmɔ – or whosoever – had sent Guilherme to her. Perhaps it was relief I felt as Ada struggled to her feet: relief because my work for this part of the story had been done. Ada stumbled along behind Guilherme, and he carried her treasured belongings away from the hut.

And the toothless ones were not alone among the living to observe this strange scenario from a rain-sheltered hiding place.

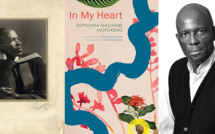

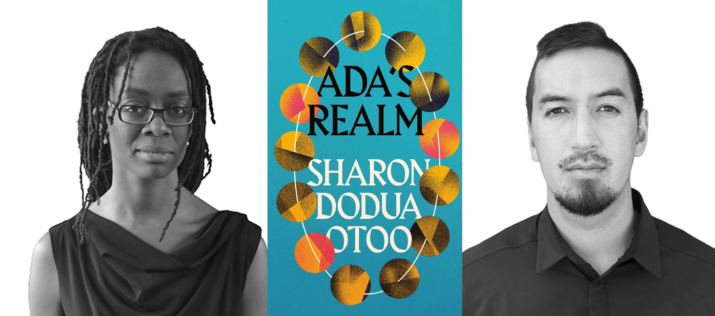

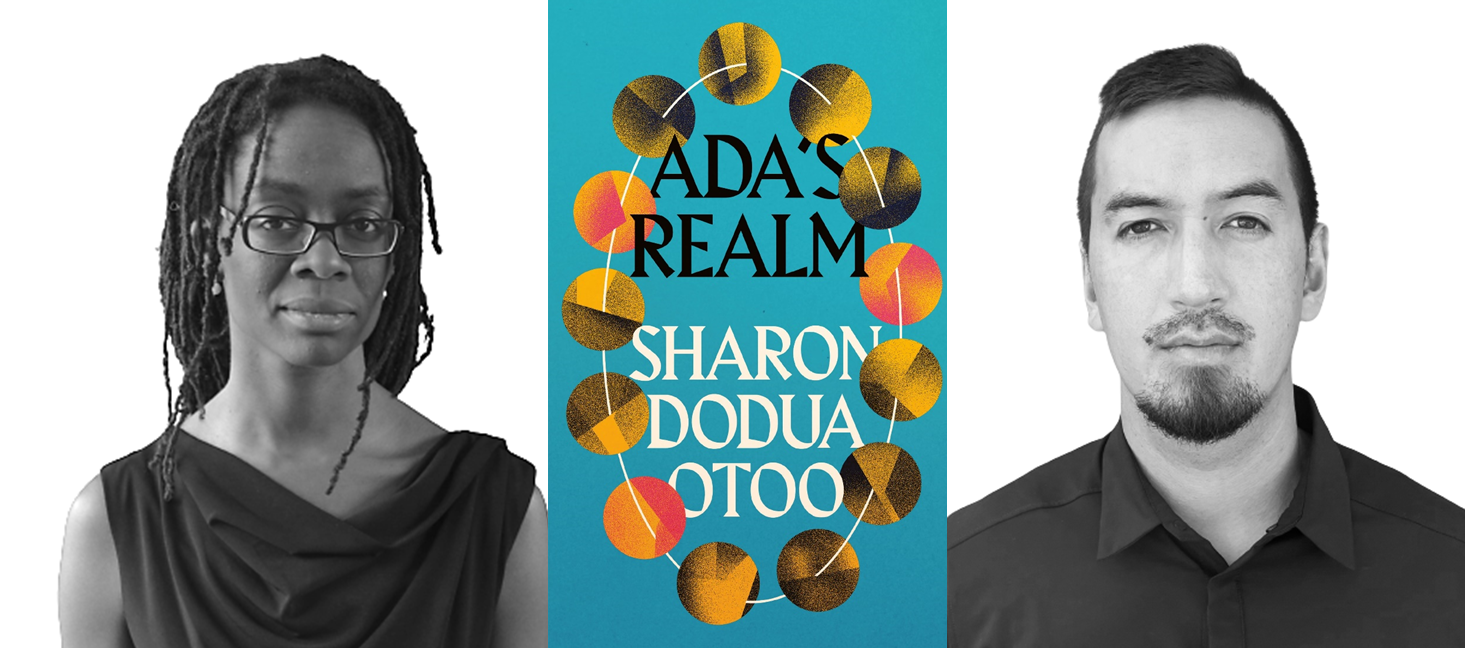

This excerpt from ADA’S REALM was published by permission of MacLehose Press. Copyright © by Sharon Dodua Otoo, 2023. English translation copyright © by Jon Cho-Polizzi, 2023.

Photo Sharon Dodua Otoo copyright © Ralf Steinberger.

Photo Jon Cho-Polizzi copyright © Jon Cho-Polizzi.

Published on February 21, 2023.