This is part of our special feature, Decolonizing European Memory Cultures.

This is part of our special feature, Decolonizing European Memory Cultures.

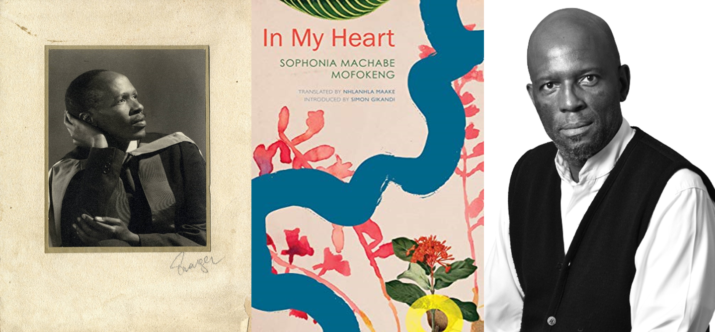

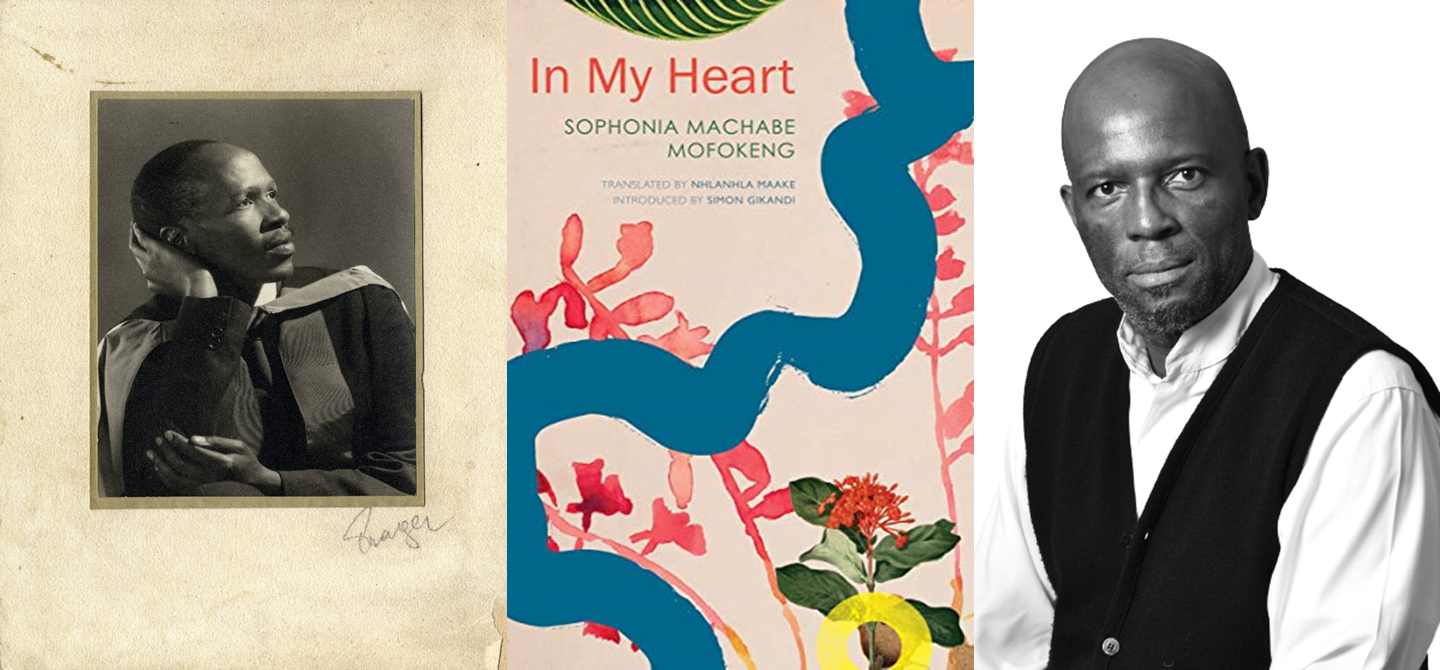

Translated from the Sesotho by Nhlanhla Maake.

The River

My home is on the border between Lesotho and Free State. When I opened my eyes, I already knew how to say, ‘Lesotho is on the other side of the Caledon River.’ It is something that I knew so well, just like drinking water or eating. It was something that I was used to. And when you are used to something, my friend, it is not often that you think of it. You start thinking about it a lot only when it disappears or when you arrive where it does not exist. Isn’t it that even this mysterious thing that we call life, we are so used to it that we do not think about it? But the day one of us kicks the bucket, it is only then that we ask ourselves what it is exactly that went out of him.

That is how it was with me. I never thought that there could be any other boundary between two countries except a river. I had already visited the Cape Colony. When I left Free State, I found a huge boulder of a river called Orange River, which was a boundary when one crosses into the Cape Colony. After I came back from the Cape Colony, I prepared to go Johannesburg, and there I found that Transvaal was separated from Free State by the Vaal River. In another year I went to Natal, thinking of holidaying at the sea. I thought that I would see the boundary between Natal and Transvaal, because I used to hear my friend saying that the border is a small wooden notice written ‘NATAL’ on one side, and on the other ‘TRANSVAAL’. I did not believe it, just as much as I did not believe what was written in the atlas. But I was unfortunate because the train passed that place at night.

A few days ago, I got a big fright. I was going to Swaziland. I was driving a car, my small map told me that we were approaching, and I stopped, got my documents ready and proceeded. In my head I was already imagining a river, and a bridge, and on the other side of the bridge a Customs office and next to it a pole wearing a Swaziland flag. While I was imagining these things, I suddenly saw ‘You are now in Swaziland.’ I stopped the vehicle. I looked back, because I thought that I had missed the river. I found nothing, I mean not even a neatly woven little fence. I stood there surprised.

No, today I am no longer surprised. I also know why nations keep on fighting, quarreling over boundaries. It is because of such borders. These things are not even boundaries; they are just a mockery. The day they want to pick up a fight, one will wake up and yank that useless pole from the ground, and hoist it ten miles from where it was, and then war starts. Yes, today I know that the real boundary of peace between countries is a river. Today I know why the French and Germans keep quarreling about ‘natural boundaries’, which is the Rhine River. A river is the real boundary. Today I understand why people talk about ‘the Jordan Valley . . . ’ as the hymn says. Jordan separates earth and heaven and I remember pictures that I used to see in many families when I was still a child (nowadays I no longer see them, as I enter this and that house I see the picture of the head of the household and his wife standing pompously!), pictures of people disappearing in the Jordan, and when they appear yonder they appear wearing clothes that are as white as snow.

When you are standing on the bank of a river, you see yourself reflected twice, my friend. You do not only see your shadow, but you see your humanity and that of other people, because a river is just like us. Where you are standing, you see water flowing, passing by. You do not know where it comes from, and where it is going, where it has passed, what it has done on the way; you do not know where it is flowing to and what it will do on the way; who it will help and where it will end up. Life also flows that way. I say, just like the person that you meet at the crossroads—which you do not know where he is going, where he comes from, what he does and where he will end up. It does not resemble a person only through its flow, but even humanity exists in it. When you are standing at the bank of a river, you think it is deep, my friend, whereas it is only a puddle. Or you think that it is not deep because the water is clear and you can see rocks at the bottom . . . whereas these rocks are not close. When it is empty, it makes a lot of noise on stones, like a person who has shallow knowledge and annoys us with self-praise. When it is full, it flows without making noise, like a real expert who does not make noise about his knowledge. When you are standing there on the bank of the river, it is like traveling with a person that you do not know what is in his heart, because even with the river, you do not know whether it is teeming with fish or snakes, mythical snakes.

Sophonia Machabe Mofokeng (1923–1957) is the first scholar in South Africa to receive a PhD in Sesotho from the University of the Witwatersrand. He wrote the stage play Senkatana (1952), Leetong: On Pilgrimage (1952), and Pelong Ya Ka (published posthumously in 1962).

Nhlanhla Maake is an academic, fiction, and non-fiction writer and translator. He writes in Sesotho and English and has published more than twenty books. His works have won ten literary awards, inter alia, Best Translators Award in 2013 and 2014 of the SALA (South African Literary Awards) for translations of his novel and play, Letters to my Sister and welcome to the Twin-Dogs Party respectively.

This excerpt from IN MY HEART was published by permission of Seagull Books. Copyright © by Sophonia Machabe Mofokeng. English translation copyright © by Nhlanhla Maake, 2022.

Photograph Sophonia Machabe Mofokeng from archival source, T.D. Mweli Skota Papers, Historical Papers Research Archive, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. With the permission of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Photograph Nhlanhla Maake: Private

Published on February 21, 2023.