This is part of our special feature, Decolonizing European Memory Cultures.

Who is the splendidly dressed man in a blue-feathered suit whose image was placarded all over Paris last fall? What is his story? Kim Vaz-Deville, professor at Xavier University of Louisiana, gives us the answer. She was the associate curator for the exhibition that took place at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac on “The Black Indians of New Orleans.” In this interview, we delve into how the exhibit came about and how the main themes were developed to best translate local New Orleanian culture for a European audience. We discuss how issues of race, enslavement, and spirituality came together to create the tradition of the “Black maskers,” which is little known outside of Louisiana. The story of the maskers Vaz-Deville tells reveals how they take great care to conceive, design, and create their suits, influenced by Native American ceremonial attires but also incorporating African symbols and more recent cultural signifiers. This complex process of cultural fusion, resulting from meticulous and intentional borrowing, adopting, and adapting of specific markers finds its physical realization in the suits sported by characters who are created to participate in the walking and carnival traditions of New Orleans. Vaz-Deville teaches us to read the maskers’ suits as texts that map a history of oppression, resistance, resilience, and rejuvenation, a trajectory that also mirrors the history of the city of New Orleans—from its role as the largest slave market in the US to the destruction and despair the city faced in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Beyond enlightening us about the artifacts themselves, Vaz-Deville brings to the fore important questions about the “making of” art exhibits and the ways in which cross-border and cross-cultural collaborations can be fostered to yield a mutual enrichment. In telling the story of how the New Orleans maskers came to Europe, Vaz-Deville not only addresses the way in which international collaborations in the art sector can be imagined and implemented but also underlines that it is crucial to encourage and facilitate the circulation of cultural artifacts from collections to collections. Indeed, as objects circulate, so do ideas, generating unexpected synergies that help in confronting difficult and painful histories that are rooted in place.

—Hélène B. Ducros for EuropeNow

EuropeNow You were recently the associate curator for the superb and thought-provoking exhibit at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris-Jacques Chirac entitled “The Black Indians of New Orleans.” How did it start? How did you imagine this exhibit and collaborate with the French museum?

Kim Vaz-Deville The way the two worlds—Paris and New Orleans—came together is the result of different conjunctures. Some time ago, I went to the Louisiana State Museum Presbytère because I was interested to curate an exhibit on spirituality and African American Mardi Gras. The first thing Karen Leathem, the historian there, mentioned was that Steve Bourget, from the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, was interested in doing an exhibit on Black Indians. He would be in New Orleans soon and able to attend my meeting with the Louisiana State Museum. That allowed us to work together from the inception of the Black Indians exhibit.

The particular exhibit I had conceptualized was broader than the Black masking Indian tradition; it was centered on spirituality, which I had begun to investigate in our walking traditions, which include our Baby Dolls, Black Masking Indians, and Skull and Bone traditions, as well as in our parading traditions. The latter entail flatbed trailers that are decorated according to specific themes. I was looking at how, for many of the people in those walking traditions, the sacred is part of everyday life. For them, Mardi Gras is not simply some event but a culmination of the way in which they express spirituality in material culture, textiles, and accessories, as well as through performance. Others in the more secular masking and carnival traditions, such as the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, were also reminiscent of African practices. For example, they had the “witch doctor,” who embodied a medicine man in the African tradition and who would be completely connected to the world of the spirit and the world of healing. His role was undoubtedly caricatured, but it was crucial. Very often, African Americans could only hold on to their African culture precisely through caricature, and I thought that it was an important inflexion point to say that part of this African thinking is still present. There were other personalities, as well as issues of governance, that were reflected in the characters of the Zulus. Back in the 1910s, these practices were some of the few ways through which African Americans could stay connected to their African heritage.

The more modern krewes[1] started in the mid-1980s, and some of the people involved had probably little connection with the spiritual aspect of the Yoruba, but they nonetheless chose Oshun as their goddess because they looked at what the European-American krewes were doing, in terms of their use of Greco-Roman gods. They thought they would use African deities, as well as the implements that went along with those gods. For example, Oshun loves mirrors, peacock feathers, fine jewelry, or beautiful hair combs. These items constitute very special throws during Mardi Gras. Throws are the distinct things that are given out during Mardi Gras and are symbols of each krewe. I also knew that there were members of the Louisiana Voodoo community who were involved in Mardi Gras; so I became interested in them as well. There have been other religions represented. For example, some Black maskers wore Mardi Gras regalia, or “suits,” that reflected the Nation of Islam, which is a more recent religion that African Americans became drawn to in the 1930s and that reached its zenith in the persons of Malcom X and Elijah Muhammad. It is still an important force.

I began to recognize all those symbols in the suits worn by the Black maskers. Those in very traditional Black masking tribes have typically used Native American representations and symbols, such as red faces, beads, and feathers, but also the figure of the United States soldier, usually portrayed as being victorious over outside forces. Some maskers from these traditional masking tribes have also sought to step outside of those representations to incorporate religious themes. For example, Devon Moore, the gravedigger of a group called the Golden Comanche goes along with a shovel, which is highly ornate to match his suit; when he comes across another tribe—these tribes usually meet and have symbolic contests about who looks the best—he confronts the members of that tribe and acts as if he digs their grave if their suits do not exceed their tribe’s artistry.

Moore also found out about certain cloaks that are used in ancestor reverence rituals in Benin and Nigeria (Figure 1). He adopted some of these traditions and the idea of the mask. He had to wear a mask because the spirits’ faces are always covered since they are too powerful for human eyes. However, the idea of his particular mask also came from the Korean TV series “Squid Game.” In the end, so much of the masking has to do with death, although this may be subconscious on the part of the maskers.

The overall conception of spirituality, as it flows through these different dimensions of Mardi Gras and Mardi Gras related activities was the core of the show I organized at the Louisiana State Museum, “Mystery in Motion: African American Spirituality in Mardi Gras.” We were able to look at the collection catalog of the Musée du Quai Branly and selected pieces to incorporate in the show in New Orleans. The pieces we chose highlighted the symbolic aspect of the artifacts that the New Orleans maskers use.

For example, in that show, we included a Big Chief who made three different suits to represent Haile Selassie, who, when he was Emperor of Ethiopia, gave artifacts to the President of France, which are kept at the Musée du Quai Branly. These artifacts were loaned to us to put on display, along with some Yoruba Shango implements and a beautiful Haitian drapeau of the Haitian Vodou loa, Guede, who is the guardian of the cemetery, from which the North Side Bone & Skull Gang start their parade. These implements also connect to the Louisiana Voodoo heritage, which is different from the Haitian Vodou tradition.

Therefore, early on, there were already those linkages between the Musée du Quai Branly and the Louisiana State Museum, which were established through this first collaboration. Moreover, through the programming of Mystery in Motion, we had joint talks about why we selected certain items from these collections, what they represented, and what these items meant for the maskers. Unfortunately, COVID-19 happened, and Steve Bourget, the Director of the America’s collections at the French museum was not able to come back to the US. He had been collecting material and meeting with chiefs to decide what he would like to present in the exhibit in Paris. In the end, he chose some of the artifacts from the Louisiana State Museum Mystery in Motion and brought them over to Paris because we already had relationships with those maskers. As a consequence, the show in Paris on the “Black Indians” was imbued with the spirituality element that had been present in Mystery in Motion.

EuropeNow How does the history of “Black Indians” in New Orleans help us better understand the history of European colonization in the Americas? What were the main axes of reflection that led you throughout the making of the exhibit?

Kim Vaz-Deville Steve Bourget thought that European audiences needed contextualization about the history of France in the Americas. Therefore, the exhibit included an in-depth history of the French presence there, from the search for gold and other natural resources to the thirst for cotton, which of course all drove the slave trade. The show explains how enslaved Africans were brought to the Americas and first came into contact with Native Americans, with whom they shared experiences, especially in terms of rituals and music, as well as the idea of moving in harmony with the environment. The Europeans were successful in exploiting both those groups; therefore, Native Americans and enslaved Africans found a common cause. However, in some other ways, they did not, since there were Native Americans who in fact owned slaves and retained anti-Black attitudes. However, there were indeed some Native Americans who lived in Maroon societies with the African enslaved. In fact, there were many intermarriages, intermixing, and cultural exchanges at that time, which gave rise to a unique African American masking tradition. Notably, Africans developed their own masking traditions in New Orleans because they were not allowed to participate in Mardi Gras celebrations. Drawing on their own historical memories, they brought items together to develop unique practices that used materials like animal horns, feathers, or beads. African beading practices are different from Native American beading practices. All these aspects of material culture have been mixed in the masking traditions of the Black masking Indians of New Orleans.

EuropeNow In what ways do you think the exhibit succeeds in connecting a mostly French public to New Orleans as a city and to the people of New Orleans, as well as in triggering self-reflection?

Kim Vaz-Deville Steve Bourget wanted to tell European audiences about the Louisiana purchase, the continual violence perpetrated against the enslaved people, and the way in which this violence continued to keep them marginalized. New Orleans became the most notorious and largest slave market. There has been this long history of disenfranchisement of African American people even after emancipation. Moreover, the 60 or so years of the Jim Crow era kept African Americans in New Orleans in a subjugated position. Integration caused the deindustralization of the city proper and brought a lot of despair to communities. These communities have continued to use expressive arts to talk about the conditions of their lives, and every generation updates those performative customs.

The reason that Black Indians exist has to do with the idea that African Americans were made to feel like they could not identify with Africa, and they, of course, were not welcome to identify with the European and Western culture. However, the one way that they could fight back against that kind of oppression was to adopt a Mardi Gras personality that would allow them to fight white people without being murdered. They could “play” Native American quite openly on the streets on Mardi Gras day and thus challenge white people if they came by. Moreover, oppression can cause people within the same group to fight, so people who were already angry for any reason could use Mardi Gras to express that aggressivity toward each other. There is always the stereotype that Black people are violent toward each other, and this idea has haunted the Black masking Indian tradition. Black men singing and dancing in tempestuous rituals looks frightening to white people.

The idea that the tradition is an homage to the Native Americans who sheltered enslaved people has been widely circulated. I think this explanation is recent; I do not remember that it was brought up in the 1970s. In fact, people liked to play Indians; that is what they called it when white people were then not paying attention to it. Therefore, they did not have to explain what they were doing. In the 1980s, people started paying more attention to the Black community and the community felt pressed to provide explanations. On their end, the Native Americans did not understand the nature of the practice and sometimes thought that Black people were making fun of their culture. So, creating an explanation that drew from a connection between Native Americans and Blacks and pointed to the practice as an homage attempted to answer questions about the complicated meaning of Black Indian traditions. Personally, I am not convinced by this argument. I am more convinced that African Americans loved to borrow artifacts from Native Americans. African Americans love the ornate and ostentatiousness, which is not seen as a negative trait. Black people like things that shine in the sun, twirl, whirl, and sway in the wind, and they embellish clothing and accessories based on this aesthetic. Anthropologist and writer, Zora Neale Hurston, called it “the will to adorn.” Black people were fascinated with the highly ritualized Native American suits and aesthetics. At the same time, the practice allowed them to take on other identities, be combative, and confront white oppression in ritualized ways. And they could to it every year at Mardi Gras.

Something that I perhaps was not able to communicate to visitors and reporters was that I found out that the French use the word “costume” to translate “suit.” People in the Black masking tradition do not call what they wear a “costume.” That term is offensive to them. “Regalia” might have worked better, if such a word exists in French. The Baby Dolls do not use that word either, because what they wear is not a disguise. Embedded in the Black culture, the idea of a suit is a formal thing that is imbued with special elegance. It is something special and sacred.

Some maskers were able to come see the exhibit, perform there, and participate in the symposium that was held in conjunction. For example, Victor Harris, probably the most esteemed Black masking Indian was invited. Moreover, his suit was bought by the museum and is now part of the permanent collection. Other maskers were also there, such as the Medicine Man, whose image was all over Paris. They saw the show, and they felt marvelous. We love our culture, but we did not realize how much our culture is loved elsewhere too. We were shocked at how much people loved it, related to it, and got joy from it.

We also learned that the maskers use items that are very specific to the Louisiana environment, such as moss or fish bones, and incorporate those in their suits. Consequently, we encountered some problems with getting clearance for some of the materials. Not being able to get items through custom is another way that things get lost in translation. Some of these materials are very important to the maskers but they have to be sanctioned by the government to get out of or into a country. That is another limitation on what can be shown to audiences outside Louisiana. Moving these suits across borders is also physically difficult. Professional art packers were hired. The portage of these suits was complicated and the museum invested a lot in getting them to Paris. Some were damaged during transport, and they made a mini-documentary about the repair, which became part of the exhibit media. These experts took a lot of care with all of the material.

EuropeNow As a scholar specialized in the African-American cultures of New Orleans, living yourself in New Orleans, and a participant in the cultural masking practice (Figure 2), what unique perspective were you able to bring to shape the narrative presented to visitors of the exhibit?

Kim Vaz-Deville I think I brought the angle of spirituality, which might have been missed otherwise. Most of these practices are truly spiritual, so if you do not analyze them from the perspective of spirituality, you miss the entire history of the Black Pentecostal Church. These Pentecostal practices have African elements in them such as being ridden by the spirit, speaking in an unknown language, or playing the tambourine, which took the place of drums when these were outlawed. The exhibit does address this facet in one of the sections where most of the suits displayed have an explicit spiritual dimension, even if the interpretive labels did not go in details about it. Still these suits were important to give a political perspective that made people connect the suits with the Black maskers’ explicit spirituality, for example through the image of the Black Hawk.

EuropeNow How different would this exhibit have been if presented to an American audience?

Kim Vaz-Deville A white American audience would need the same contextualization as Europeans. It is difficult to read all these symbols. We do not score well in the US on knowing that kind of culture. The focus was to stress how centuries of exploitation have been manifested through material and performative culture. With the onslaught of critical race theory and the banning of certain aspects of African American studies, audiences will increasingly need this sort of contextualization, even here in the US. Moreover, New Orleans does not necessarily translate well in other parts of the country. People do not know about this tradition, so contextualization would be needed for an American audience, although there could be less about history and more about the practices and traditions. Even Blacks outside New Orleans may not know about the practice. The reason is that this tradition is anchored in the neighborhoods of the city. It only really became popular since Hurricane Katrina. In the 1960s, people disregarded the culture because integration destroyed neighborhoods where these traditional cultures had been created, practiced, fostered, and perpetuated. So, they were seen as passé; folk culture died with the younger generations. Katrina, as the whole city was dying, brought the fear of losing the culture. As a result, we have approximately forty Black masking tribes today, while there were only a dozen of them from the 1920s to the 1950s.

EuropeNow How do you think we can foster these sorts of multidirectional cultural exchanges in the future? What other conduits do you think might open the conversation?

Kim Vaz-Deville There was an interesting moment recently, when President Macron came to New Orleans and gave a speech at the New Orleans Museum of Art. Nick Cave’s soundsuit was in the background. So that the whole time Macron was speaking about the French language in Louisiana, you also could see the suit that was created after the beating of Rodney King and that symbolizes a protest against the dehumanization of Black people. In a way, it echoed the mystic Medicine Man whose suit objects to European colonization and whose image you could see on the building of the Musée du Quai Branly with the Eiffel Tower in the background (Figure 3). I think that these kinds of synchronicities are interesting to notice.

EuropeNow Scholars in different fields have increasingly considered the concept of “decolonizing” the arts and museums, especially in Europe where many countries were imperial powers. How do you understand that concept and the work it does?

Kim Vaz-Deville It is important to display material culture to encourage a conversation. However, the one problem in museography and museum studies is that not enough people of color are hired, sit on boards, or are in key positions. Therefore, you are missing people who have the necessary training and sensitivity to face those issues and have the relationships with the communities at stake. If these people were involved, it would prevent institutions that want to display other peoples’ artifacts from making all kinds of mistaken assumptions. I think that all of these institutions could do a much better job at integrating local communities into the work that they do. For example, I had no idea that in Paris, not that far from the Musée du Quai Branly, live large African and North African communities. Why weren’t they part of our programming? I think that in many ways, the exhibit was intended for white Europeans, as opposed to Europeans of color.

EuropeNow What is next on your agenda? What can we look forward to in your work?

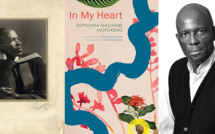

Kim Vaz-Deville I am currently writing the authorized biography of the former president of Xavier University of Louisiana, Norman Francis. Francis was president from 1968-2015, making him the longest serving head educational administrator in the nation. Most importantly, he was at the cusp of every aspect of the civil rights movement, allowing us to see Black history from the perspective of someone in the deep South. I also won the 2023-2024 National Endowment for the Humanities Faculty Award and a Louisville Institute Sabbatical grant to write a book on the art of spiritual resistance in Black Mardi Gras. I will be participating in a panel on creolization that will take place in Vienna, Austria, in May. I will speak about the Baby Doll tradition, aesthetics, and performativity. And finally, I am also involved with the Women in Carnival Research Network, a group of women who focus on African American women or women of African descent in Caribbean and English carnivals. The network includes both scholars and practitioners. Much is happening in this field, and New Orleans is considered to be within the Caribbean scope.

Kim Vaz-Deville, professor of education at Xavier University of Louisiana, curated Louisiana State Museum’s exhibition entitled “They Call Me Baby Doll: A Mardi Gras Tradition” (2013). She is the author of The ‘Baby Dolls’: Breaking the Race and Gender Barriers of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Tradition (LSU Press, 2013) and the editor of Walking Raddy: The Baby Dolls of New Orleans (University Press of Mississippi, 2018). She also brings personal experience with Black masking traditions. Her St. Martha the Dragon Slayer suit, which she wore as part of the Golden Feather Hunters tribe in 2020, was featured in the Louisiana State Museum’s 2021 exhibition “Mystery in Motion: African American Masking and Spirituality in Mardi Gras” at the Presbytère in New Orleans and in the 2022 exhibition titled “The Black Indians of New Orleans” at the Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac Museum.

Hélène B. Ducros, JD, PhD, is a human geographer whose research has focused on place-making through heritage-making, landscapes of remembrance and commemoration, and the circulation of cultural models of heritage preservation. Her latest publication is Justice in Climate Action Planning (co-edited with Brian Petersen, Springer Nature, 2022). She is founding chair of the Critical European Studies Research Network at the Council for European Studies and teaches at Xavier University of Louisiana.

[1] Krewes are organizations involved in the preparation of parades or other performances during a carnival celebration. In the US, krewes are especially associated with Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

Images of the exhibit by Hélène Ducros

Published on February 21, 2023.