This is part of our special feature, Decolonizing European Memory Cultures.

British Muslim Women in the Cultural and Creative Industries examines the role of Muslim women in media, fashion, and the visual arts in Britain. Although the book offers glimpses of the creative work itself, its focus is on the creators, their labor, agency, and influence, as well as on the challenges they face as Muslims, women, and members of ethnic minorities. The author argues that gender and class have been studied as social factors in Britain but that religion and faith have been taken out of the equation. Muslim women are still significantly underrepresented in the British paid workforce, yet they have increasingly contributed to the fast-growing “Islamic” cultural and creative industries. An intersectional approach that draws on the theories of Kimberlé Crenshaw and others helps this study present a nuanced picture of British Muslim women’s multiple identities. This book describes these women’s struggles against social and economic marginalization, often citing their own words gleaned through interviews and diaries. It also offers uplifting examples of their success in creative endeavors, advocacy, and community building.

British Muslim Women in the Cultural and Creative Industries examines the role of Muslim women in media, fashion, and the visual arts in Britain. Although the book offers glimpses of the creative work itself, its focus is on the creators, their labor, agency, and influence, as well as on the challenges they face as Muslims, women, and members of ethnic minorities. The author argues that gender and class have been studied as social factors in Britain but that religion and faith have been taken out of the equation. Muslim women are still significantly underrepresented in the British paid workforce, yet they have increasingly contributed to the fast-growing “Islamic” cultural and creative industries. An intersectional approach that draws on the theories of Kimberlé Crenshaw and others helps this study present a nuanced picture of British Muslim women’s multiple identities. This book describes these women’s struggles against social and economic marginalization, often citing their own words gleaned through interviews and diaries. It also offers uplifting examples of their success in creative endeavors, advocacy, and community building.

Author Saskia Warren, a Senior Lecturer in Human Geography at the University of Manchester, holds a doctorate in cultural geography and art theory and a Master’s in art gallery and museum studies. According to her website, her research focuses on social and spatial inequalities. In the book, Warren makes frequent reference to concepts such as the “geographical glass ceiling,” by which artists or fashion designers in communities outside major metropolitan areas find themselves under-resourced and overlooked. She provides detailed facts and statistics about the British Muslim female population in specific geographic locations, particularly Greater Manchester, home to one of the largest Muslim populations in the country. The current study is the product of a research grant from the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council, as was the exhibit Warren co-curated, Beyond Faith: Muslim Women Artists Today, which featured five contemporary artists working in a variety of media. Warren conducted fieldwork from 2017 to 2020, including interviews and focus groups with 120 people in the greater Manchester region. Her book also draws on an extensive bibliography of theoretical works, sociological studies, government reports, art exhibition catalogs, and more. Clearly, there has been scholarly interest in the intersection of Islam, creativity, and activism, for example in Lewis and Hamid’s British Muslims: New Directions in Islamic Thought, Creativity and Activism (2018), also published by Edinburgh University Press, which examines the contributions of Muslims to cultural work and the challenges they face. Warren’s study builds on this work while bringing a focus on gender. Her interviews with Muslim women reveal the barriers they face in entering and progressing in Britain’s fashion, textile, art, and media industries and the challenges they encounter in finding jobs and fitting in these spaces of social privilege.

The book provides context around religion, ethnicity, gender, and labor, for example stating that in Britain, Muslims comprise around 4.8% of the total population. In Greater Manchester, white Brits’ employment rate was almost 73% in 2019 while Brits of “non-white minority ethnic backgrounds” experienced rates of around 53%. Even more pronounced is the difference in British labor force participation for Muslim women compared to non-Muslim women. When seeking waged employment, Muslim women face barriers similar to those other British women face, including in the form of gender discrimination, rigid work schedules, and lack of affordable childcare, but they also contend with racial discrimination and Islamophobia.

Warren argues that Muslim women are marginalized in Britain’s creative industries where male, white, and secular features are maintained as the norm. Overall, fewer women are employed in the creative industries than men, and they earn lower wages than their male counterparts; for example, women comprise less than a third of the artists represented by commercial galleries in London and make only a third of the top earners at the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Muslim women artists, designers, or vloggers confront particular obstacles that range from “integrated casting”—or tokenism—in exhibition spaces to cyberattacks. Muslim women who want to work in the cultural and creative industries also meet reluctance from their families and communities to see these fields as prestigious. Moreover, some Muslims consider certain forms of visual and performing arts as questionable in light of their religious standards.

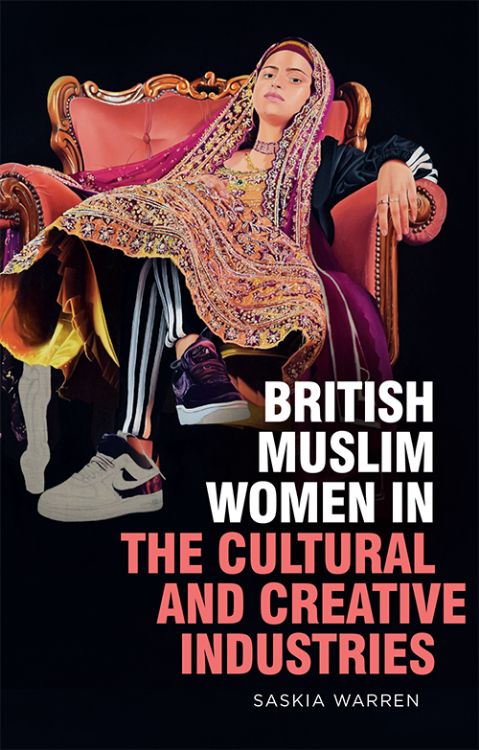

The book also provides an examination of the challenges Muslim women face at British art schools, which are institutions that, according to the author, have tended to reproduce inequalities in terms of location (urban vs. rural), opportunities, and even the styles and subject matter that are encouraged. Warren argues that British art schools, “enmeshed with empire and colonialism” (97), have functioned as a “dominant white space,” citing a 2020 report showing that creative arts and design was the university discipline area with the highest proportion of white students (82%) and only 2% of students identifying as Asian (92). For Muslim women attending art schools, a number of situations potentially cause conflict or unease. They may have to deliver assignments that require figurative approaches to representation or life drawing of nude models. Classes entail ‘free mixing’ of men and women and exposure to drinking cultures at “boozy” art openings or student and faculty gatherings at pubs. Moreover, some Muslim women artists feel “conflicted” and “exposed” when professors pressure them to represent their personal identity in their artwork, while others have embraced the opportunity to bring their religious identity to the forefront. For example, Warren offers the case of Azraa Motala who painted a self-portrait entitled “I beg you to define me,” representing herself reclining in an armchair, dressed in a South Asian head covering, a track suit, and Nike sport shoes. For her MA final show, Motala hung the portrait as a larger-than-lifesize banner on the front of the Chelsea College of Arts. For Warren, this act symbolically disrupts public space, “unsettle[s] the historic marginalisation of Muslim cultures as inferior” and “subvert[s] the Western male artistic gaze of the Muslim woman as odalisque” (118). Motala’s compelling image even graces Warren’s book cover.

Another area where Muslim women artists have gained recognition is through media platforms, particularly when producing content for other Muslim women. Traditional Muslim and Western-liberal media have been dominated by male voices, but “hijabi bloggers,” female journalists, and TV show hosts are creating “spaces of solidarity and belonging” that are important in a society in which Muslim women form the group that feels the most excluded (134). Warren cites examples such as the British hijabi fashion blogger Dina Torkia, who has 1.3 million Instagram followers and has appeared on the cover of Vogue. Indeed, Torkia and others like her discuss topics ranging from modest fashion, honor killing and female genital mutilation to living as a Muslim in the West and women’s rights in the Qur’an. Torkia’s film #YourAverageMuslim has challenged stereotypes while (ironically) also critiquing the constant push for Muslim women to challenge stereotypes. Warren cites the British television show Sisters’ Hour as evidence of women’s efforts to promote tolerance and dialogue among Muslims of various identities. All these creative endeavors are interpreted by the author not only as challenges to patriarchy and imperialism but also as signs that creative labor can be community-oriented and faith-based rather than individualistic and secular.

When reflecting on modest fashion and textiles, Warren distinguishes between the “sewing and cutting” that Muslim women have traditionally done from home while caring for their families, as well as the work of “proper fashion” that may carry prestige but is unfriendly to women and mothers. Modest fashion purchased by Muslim women accounts for $360 billion; moreover, high street brands such as H&M and Nike and luxury brands such as Versace or Chanel have offered pieces of clothing such as abayas and headscarves. However, generally, fashion design remains a space of exclusion for British Muslim women. Counterbalancing these challenges faced by Muslim women in the cultural and creative industries, the book offers portraits of successful Muslim women in those industries. A chapter on “Visual Arts and the Art World,” profiles contemporary women artists who work in digital Islamic art and combine traditional craft and new technologies, such as Sara Choudhrey, a London-based artist-researcher, and Zarah Hussain, who creates hand-drawn geometric designs enhanced with digital software. Warren also references the exhibit she co-curated, Beyond Faith: Muslim Women Artists Today, at the Whitworth Gallery in Manchester in 2019-20. This effort helps situate Warren herself among the feminist activists who have worked to amplify Muslim women’s voices and promote their visibility.

The book also examines the ways in which Muslim women have combined creativity and civic activism to build a community of believers and teach others to respect Islam. The author summarizes a body of research on Muslims’ activism and draws on her own work based on interviews, focus groups, and respondents’ diaries to better understand Muslim women’s work lives. She reports on some of the diary entries these women wrote in 2017 when a white supremacist organized a hate event called “Punish a Muslim Day,” highlighting that several respondents, among them Dina Torkia, wrote that fear kept them home that day.

By taking stock of the challenges and successes of British Muslim women in the creative industries, Warren argues that British policy towards culture and the arts needs to evolve to recognize a diversity of expression and beliefs and to create greater access and a fairer distribution of resources. She laments the continued lack of “ethnic diversity or women’s leadership across most sub-sectors of the cultural and creative industries” despite “decades of talk” (275). Additionally, as her study itself was funded by a government grant, she subtly advocates for publicly funded assistance to Muslim women artists, which would be “a sign of justice, recognition, respect, and support by the state” (275). This detailed, substantive study will be of interest to academics in human geography, sociology and the arts, as well as to Muslim women in the cultural and creative industries, other leaders in these fields, administrators in schools of art, design, and communication, and political decision-makers at local and national levels. While Warren’s research focuses specifically on England, the questions posed are broadly relevant to a pan-European context. Warren’s repeated interrogation about religion as a criterion of inclusion is an important one in a so-called “post-secular” Europe where Islam as an identity and as a lived practice is thriving.

Mary B. Vogl is a professor of French and Francophone Studies at Colorado State University. She is the author of Picturing the Maghreb: Literature, Photography, Representation (Rowman & Littlefield 2002) and articles on North African literature, art, and aesthetics.

British Muslim Women in the Cultural and Creative Industries

By Saskia Warren

Edinburgh University Press

Hardcover / 352 pages / 2022

ISBN: 9781474459310

Published on February 21, 2023.