Cocoa Beans Do Not Grow in the Swiss Mountains: Swiss Public Museums of Modern and Contemporary Art and the Winds of Decolonial Change

This is part of our special feature, Decolonizing European Memory Cultures.

Switzerland is known for its pristine lakes, snowy mountains, cleanliness, banking confidentiality, diplomatic neutrality, the Red Cross, fondue anytime of the year, luxury watches, Roger Federer’s forehand shot, and chocolatiers’ savoir-faire. The image is as glossy as the Leman Lake on a summer day. Yet a closer examination reveals some cracks in the shiny surface. In 2021, an “anti-burqa” [sic] referendum passed whereas only a few dozens of women wear the niqab among the 390,000 Muslims living in Switzerland.[1] In May 2022, more than 70 percent of the population voted in favor of Swiss funding to Frontex, the European agency managing border patrols and coast guards, to restrict even more the opportunities for access to Fortress Europe and control immigration. Swiss banks have regularly been embroiled in financial scandals, in particular Crédit Suisse, which has lately been involved in the so-called “tuna bond” corruption scandal in Mozambique, triggering a devastating economic crisis in that country. Corporations such as Glencore, one of the world’s largest companies specializing in trade, brokerage, and raw materials extraction, have repeatedly been condemned for their ruthlessly extractionist practices. Recent investigations have shown that Swiss agricultural traders own more than 27 million hectares of plantations overseas, where they are directly responsible for brutal expropriation, labor abuses, and environmental damages (Public Eye 2022). These few examples demonstrate that Switzerland has not been exempt from racist (Michel 2015, Jain 2018, Dos Santos Pinto et al. 2022) and neocolonial politics. In fact, Switzerland has had a major role in the destruction of Global South economies and environments.

Until the emergence of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, Switzerland’s leaders publicly claimed that the country never played a role in the slave trade or the colonial enterprise, despite clear historical evidence unveiled by researchers to the contrary over the past few decades (Debrunner 1991, Fässler 2005, Harries 2007, Zangger 2011, Purtschert et al. 2012, Berlowitz and al. 2013, Zürcher 2014, Schär 2015, Purtschert and Fischer-Tiné 2015, Germann 2016). A recent Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) research project entitled “The Exotic? Integration, Exhibition, and Imitation of non-Western Material Culture in Europe (1600-1800)” highlighted that Swiss historical museum collections and archives have been filled with objects, artifacts, and documents related to colonial activities since the eighteenth century (Étienne et al. 2020). For example, the presence of a gymnotus, a tropical electric fish, in the collection of the Académie de Genève library tells the individual trajectory of a Genevan man who brought the fish back from Surinam where he had gone to manage a plantation that he inherited in the 1750s. Moreover, drawings from New Bern, North Carolina, confirm that Switzerland was inscribed in the global enterprise of colonization, even if it was only present in limited areas that were under the protection of the British Crown (see Brizon 2019). As feminist philosopher Patricia Purtschert wrote in her introduction to Colonial Switzerland, now is the end of innocence (Purtschert and Fischer-Tiné 2015), and the current consensus is that the country practiced a “colonialism without colonies” and contributed to the European colonial enterprise. As Purtschert stated, the “decolonial narrative thus follows the idea that repressed and forgotten histories cannot simply be added to existing history (…). Rather, it is about collectively rediscovering how the national community in which we live was formed and how we want to and can continue to live within” (Purtschert 2019, 18). Hence, how does this decolonial narrative translate in terms of political agenda and find echoes in the civil society?

The tip of the iceberg

Museum collections and exhibitions programming indicate how societal issues are addressed during a given period. An examination of the main public Swiss modern and contemporary art museums[2] over the last twenty years reveals that there has been no change in the ways in which collections have been displayed, in contrast to what other European museums have done. For example, the Tate Britain in 2012 with Migrations: Journeys into British Art or the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2013-15 with Modernités plurielles de 1905 à 1970 offered new insights into collections by considering the respective colonial and post-colonial histories of the UK and France, and included artists from Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPoC) communities, non-Western artists and artists from non-Western migration backgrounds[3] in the art historical narrative. By contrast, in Switzerland there has been no record of any group show addressing these questions in the major public modern and contemporary art museums.[4] Although the importance and relevance of these topics in the Swiss context is undeniable, their absence from the main museums triggers the question whether curators are too timid to address such issues, or reluctant to contradict a prevailing political commonsense.

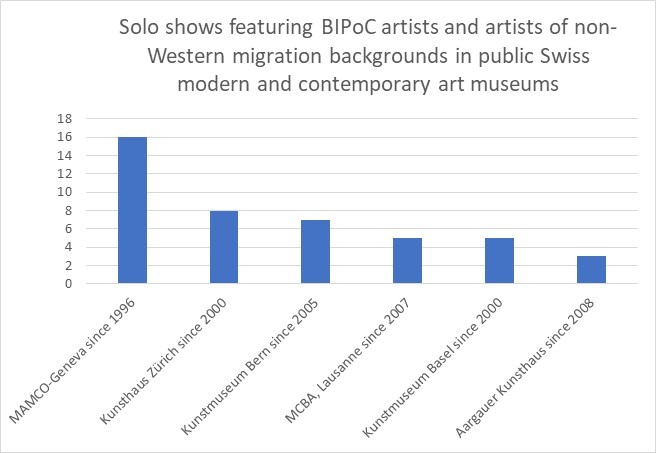

To answer this question, each specific case should be studied independently; however, a general trend can be identified in Swiss public museums of art overall. Solo shows seem to represent a fertile entry point into the matter, because they have included non-Western artists, BIPoC artists and artists from non-Western migration background in the Swiss artistic landscape (although not systematically), and addressed (post)colonial history and issues. A brief survey of these recent exhibits reveals dismal numbers: the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain (MAMCO) in Geneva organized 16 such solo shows since 1996; the Kunsthaus Zürich hosted 8 exhibitions out of 234 since 2000 that were devoted to non-Western artists or artists with non-Western migration backgrounds; the Kunstmuseum Bern organized 7 such solo shows since 2005; the Musée Cantonal des beaux-arts (MCBA) in Lausanne 5 exhibitions since 2007; the Kunstmuseum Basel 5 solo shows since 2000; and the Aargauer Kunsthaus 3 exhibitions since 2008.

Exhibitions are only the tip of the iceberg. When BIPoC artists, non-Western artists, or artists from non-Western migration backgrounds are able on occasion to exhibit their work in major Swiss public museums of art, their inclusion shows that they have become recognized as making contributions to the arts. However, if these artists’ works do not enter permanent collections and are not regularly exhibited, the mainstream narrative is likely not going to be shaken. In the USA, the 2022 Burns Halperin Report revealed that even though the art world is perceived as being progressive and is an advocate for the #metoo and BLM movements, the reality is different. Looking at a dataset of 31 museums across the country from 2008 until 2022, the 2022 Burns Halperin Report shows that Black American and women artists are underrepresented in museum collections and exhibition programming; indeed, women artists are represented in only 11 percent of the acquisitions, while Black American artists represent 2.2 percent and Black women artists 0.2 percent (Burns and Halperin 2022). Such a report does not exist for Switzerland, although it is sorely needed. Nevertheless, numbers are telling.[5] The MAMCO collection counts more than 6,000 artworks dating from the second half of the twentieth century to the present, of which only 133 were produced by BIPoC artists, non-Western artists, and artists from non-Western migration backgrounds.[6] The MCBA in Lausanne owns a collection of more than 10,000 artworks, of which only nine were created by BIPoC artists, non-Western artists, or artists from non-Western migration backgrounds; moreover, these creations were usually purchased or gifted on the occasion of a personal solo show hosted by the museum.[7] The latest acquisition at the MCBA has been Lubaina Himid’s painting Accidental Encounter (2021), which she presented at her solo show So Many Dreams there (2022-2023). The Kunstmuseum Basel, the world’s oldest public art collection, encompasses more than 300,000 pieces from the late Middle Ages to the present. Only eleven BIPoC artists or artists from non-Western migration backgrounds are part of that collection, with African American Kara Walker contributing the greatest number of artworks among those. The museum purchased 41 drawings after her solo show in 2021, which constituted her first solo show in Switzerland. Moreover, one painting and eleven drawings by British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boyake were purchased in 2016 after the completion of her solo show at the Kunsthalle Basel. The latter’s programming stands out from that of the nearby Kunstmuseum, as it has organized 38 solo shows featuring BIPoC artists, non-Western artists, and artists from non-Western migration backgrounds since 2001. Moreover, the Aargauer Kunsthaus in Aarau owns the largest collection of Swiss art, with more than 20,000 artworks dating from the eighteenth century to the present. Out of the 317 artists represented there, only six come from a non-Western migration background, and none of them are of African descent.[8] In Zürich, the Kunsthaus collection includes more than 4,000 paintings and sculptures and 95,000 graphic artworks dating from the thirteenth century to the present, encompassing 5,000 artists. Out of all the artists represented in the museum’s twentieth and twenty-first century collection, only nineteen are BIPoC artists, artists with a history of non-Western migration, or non-Western artists. In the same way that Switzerland as a nation has long repressed its implication in colonialism, it still wants to see itself as entirely white and has a long way to go before collections in major public art museums reflect the demographic reality of its population[9].

Beyond representation

The MAMCO’s website states that

Yet, the globalizing imperative to bring in “differences” is not enough to resolve the issues coming from a dominant ideology. For a museum like MAMCO, what is at stake is rather to gauge to what extent taking into account these differences modifies our understanding of the forms and practices we collect. What should be considered is our conception of recent historiography, and the division of its periods, as much as the aesthetic contours applied to the movements in question. (…) In other words, is it possible for a museum to construct different conceptual tools, aesthetic categories, and other narratives of the passing of time as we see it, while exhibiting these artists, and thus exposing ourselves to such forms? (MAMCO 2018).

This statement was made on the occasion of a retrospective devoted to British artist Rasheed Araeen in 2018, a key artist who has contributed to the reevaluation of Western modernism and minimalism through the lens of postcolonial theory, and to the recognition and inclusion of Black British artists. The exhibition was first presented at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven (Netherlands) before coming to Geneva and then traveling to other venues; therefore, it did not start as an initiative by the MAMCO but by the Van Abbemuseum. Nonetheless, the organization of such an exhibition in a museum that essentially had shown minimalist and conceptual works only by white male artists was promising. The museum’s statement makes it clear that (decolonial) change cannot be limited to representation but requires a more profound reflection on the categories and canons that have ruled our understanding of modern and contemporary art, which has been Eurocentric. The implementation of such a reflection may take time and require experts and education; however, it is nonetheless disappointing that, since Rasheed Araeen’s retrospective in 2018, only five exhibitions out of 66 have featured works by non-Western artists or artists from non-Western migration backgrounds.

Opening the scope of the corpus and examining art centers, Kunsthalle, and other private art spaces—and even art schools—reveal a different situation. Indeed, decolonial practices and thinking have been invented, experimented with, and promoted in Swiss art spaces for a couple of decades. For example, in 2005-2006, the Shedhalle in Zürich launched a program of exhibitions and symposiums entitled Kolonialismus ohne Kolonien? (Colonialism without Colonies?), anticipating important questions that have since been taken up in academia. It was also at the Shedhalle that the project Die ganze Welt in Zürich. Konkrete Interventionen in die Schweizer Migrationspolitik (The Whole World in Zurich: Concrete Interventions in Swiss Migration Policy) was hosted in 2015. This project provided a key impulse in the negotiation of urban citizenship in the Swiss context. The Schedhalle also organized a special program titled Decolonizing Switzerland during the celebration of Zürich’s museum night in September 2015.[10] In 2016, Kadiatou Diallo curated SCH at the Ausstellungraum Klingental in Basel. The exhibition showed the possible meaning of decolonization in Switzerland by offering different narratives that include those who have been marginalized by a predominantly white society (Diallo 2019). During the 2015-16 academic year, the CCC Research Master Program from the HEAD in Geneva organized a series of public interventions and private seminars that addressed different ways of thinking, producing and transmitting knowledge through a decolonial prism (Mende 2017). In June 2017, the Postgraduate Program in Curating of the Zürich University of the Arts (ZHdK) organized a symposium at the Kunstmuseum Basel entitled De-Colonizing Art Institutions, to which various art world professionals from around the world were invited to share their experiences as cultural producers and to debate possible strategies (Kolb and Richter 2017).

In June 2020, 76 Swiss institutions participated in #BlackOutTuesday on social networks in solidarity with the BLM movement. In response to this public stand against racism, more than sixty artists and cultural workers in Switzerland challenged these institutions in an open letter to make concrete proposals to tackle the problem of systemic racism (Black Artists and Cultural Workers in Switzerland 2020). According to the signatories, of the 76 art spaces that were solicited for this endeavor, only three publicly shared their response to the letter. The other 73 institutions had different reactions, one of which was to expect the letter’s signatories to provide free educational workshops rather than bringing in paid experts to educate art professionals and institutions about anti-racism issues. However, the most common response was a deafening silence. The institutions were generally reluctant to address structural anti-Black racism. Some of the signatories were even asked to justify why they signed the letter, and they were victim of libel. This latest example demonstrates the need to thoroughly confront the structural blind spots rooted in white supremacy.

Until cacao trees can grow in Switzerland

Climate change may have some upsides for the chocolate industry. In a few decades, cocoa beans may be cultivated in Swiss mountains. They will no longer have to be imported from overseas, minimizing the impact on the environment, the carbon footprint, and abuses of agricultural labor. Switzerland could then produce a completely local chocolate and proudly stamp it with the Swiss flag. The future of the chocolate industry could hence be decolonized. What about Swiss public museums of modern and contemporary art? Will they come to embrace the reality of the legacies of colonial histories and the sociopolitical changes these legacies imply? Since June 2020, curators in various art spaces in Switzerland have been willing to take on decolonial issues, as evidenced by a significant and promising increase in the number of exhibitions, panel discussions, and other public events on the topic. The growing representation of BIPoC artists and artists of non-Western migration backgrounds in temporary exhibitions is to be welcomed, and the programming of the Kunsthaus Baselland or the Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Zürich in recent years has been remarkable in this respect. However, as long as these works are not widely made part of museum collections and are not regularly shown alongside the canonical works of Western art to challenge this latter category’s limits and aporias, there is little chance that their inscription in Western art history will be successful. As Yvette Mutumba stated, while co-curating the 10th Berlin Biennale in 2018, “Real decolonization has to hurt” (Kasiske 2018)—a statement that was perceived as provocative. During a more recent interview, she explained what she meant by adding that

Decolonization means that I will not do the job of those sitting inside institutions and organizations that are predominantly white. To me it means having conversations which create serious exchange, but also discomfort, maybe even pain, on the other side of the table. It means having to sit with that discomfort. It means understanding that decolonization is not a matter of ‘us’ and ‘them,’ but concerns all of us. It means acknowledging that this is not a current moment or trend. It means recognizing that BIPoC/BAME/PoC are not necessarily particularly ‘political:’ we simply do not have the choice to not be political (Larios 2020).

Indeed, the decolonizing of institutions is not limited to the choosing of new themes, the adoption of new exhibition models, or the pursuit of new research approaches. Institutions play a fundamental role and must become strong allies in this struggle. In this regard, the appointment of South African Kabelo Malatsie as director of the Kunsthalle Bern in 2022 constitutes a powerful signal that the winds of decolonial change are blowing in the right direction. Hopefully, these winds will reach every art space in Switzerland before cacao trees grow there.

Marie-Laure Allain Bonilla is teaching fellow at HEAD—Genève, HES-SO. She holds a PhD in contemporary art history from Rennes 2 University. Specialized in the history of exhibitions, her research focuses on museum acquisition policies in the global era, and the strategies to decolonize institutional practices both in the West and in former colonized areas.

This article derives from an unpublished paper delivered on July 1, 2022, at the National Institute for Art History (INHA) in Paris, as part of the seminar “Histoires multiples et narrations transnationales: Ré-orientation des musées européens,” organized by Tate Hyundai Research Center and INHA.

All translations from the German are by the author.

References

Black Artists and Cultural Workers in Switzerland, 2020. “To All Art Spaces in Switzerland.” Last modified June 9, 2020. https://tinyurl.com/58atppmc

Brizon, Claire. 2019. “Collections coloniales ? L’implication de la Suisse dans le processus d’expansion coloniale européen au siècle des Lumières.” Tsantsa Journal of the Swiss Anthropological Association 24: 24-38.

Burns, Charlotte and Julia Halperin. 2022. “Introducing the 2022 Burns Halperin Report.” Artnet News, December 13, 2022. https://tinyurl.com/3urwsn99

Debrunner, Hans Werner. 1991. Schweizer im kolonialen Afrika. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Diallo, Kadiatou. 2019. “SCH… On Curating the Unspoken and the Unspeakable.” Tsantsa Journal of the Swiss Anthropological Association 24: 78-88.

Dos Santos Pinto, Jovita, Pamela Ohene-Nyako, Mélanie-Evely Pétrémont, Anne Lavanchy, Barbara Lüthi, Patricia Purtschert, and Damir Skenderovic, eds. 2022. Un/doing Race. La Racialisation en Suisse. Zürich; Geneva: Éditions Seismo.

Étienne, Noémie, Claire Brizon, Chonja Lee and Étienne Wismer, eds. 2020. Une Suisse exotique ? – Regarder l’ailleurs en Suisse au siècle des Lumières. Zürich: Diaphanes.

Fässler, Hans. 2005. Reise in schwarz-weiss: Schweizer Ortstermine in Sachen Sklaverei. Zürich: Rotpunktverlag.

Germann, Pascal. 2016. Laboratorien der Vererbung: Rassenforschung und Humangenetik in der Schweiz, 1900-1970. Göttigen: Wallstein.

Harries, Patrick. 2007. Butterflies and Barbarians: Swiss Missionaries in South-East Africa. Oxford: James Currey.

Jain, Rohit. 2018. Kosmopolitische Pioniere. ‹Inder_innen der zweiten Generation› aus der Schweiz zwischen Assimilation, Exotik und globaler Moderne. Bielfeld: Transcript.

Kasiske, Andrea. 2018. “Berlin Biennale: ‘Real decolonization has to hurt’.” Deutsche Welle, September 6, 2018. https://tinyurl.com/ufwzmpsp

Kolb, Ronald, and Dorothee Richter, eds. 2017. “Decolonizing art institutions.” Special issue, On Curating 35.

Larios, Pablo. 2020. “Yvette Mutumba on Why Decolonizing Institutions ‘Has to Hurt’.” Frieze, July 6, 2020. https://tinyurl.com/43pb7d6j

MAMCO. 2018. “Rasheed Araeen. A retrospective.” Accessed Feb. 9, 2023. https://www.mamco.ch/fr/1503/Rasheed-Araeen

Mende, Doreen, ed. 2017. Thinking Under Turbulences. Geneva: HEAD—Genève/CCC Research Master and PhD Forum; Pully: Motto Books.

Michel, Noémi. 2015. “Sheepology: The Postcolonial Politics of Raceless Racism in Switzerland.” Postcolonial Studies 18(4): 410-426.

Public Eye, 2022. “Les territoires suisses d’outre-mer. Où les négociants agricoles suisses détiennent des plantations et de quels abus ils sont responsables.” Last modified January 24, 2022. https://plantations-suisses.ch/

Purtschert, Patricia. 2019. “Prolog: Mehr als ein Schlagwort. Dekolonisieren (in) der postkolonialen Schweiz.” Tsantsa Journal of the Swiss Anthropological Association 24: 14-23.

Purtschert, Patricia, and Harald Fischer-Tiné, eds. 2015. Colonial Switzerland: Rethinking Colonialism from the Margins. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Purtschert, Patricia, Barbara Lüthi and Francesca Falk, eds. 2012. Postkoloniale Schweiz: Formen und Folgen eines Kolonialismus ohne Kolonien. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Schär, Bernhard C. 2015. Tropenliebe. Schweizer Naturforscher und niederländischer Imperialismus in Südostasien um 1900. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Zangger, Andreas. 2011. Koloniale Schweiz. Ein Stück Globalgeschichte zwischen Europa und Südostasien (1860-1930). Bielfeld: Transcript.

Zürcher, Lukas. 2014. Die Schweiz in Ruanda. Mission, Entwicklungshilfe und nationale Selbstbestätigung (1900-1975). Zürich: Chronos.

[1] Ironically, the referendum was labeled in terms of the burqa, highlighting the racist bias of the people behind it to a greater extent. Indeed, they did not differentiate between a burqa and a niqab, which was in fact the type of veil that was targeted by the referendum.

[2] The following museums constitute the corpus of this study: MAMCO Genève, Musée cantonal des beaux-arts in Lausanne, Kunstmuseum Basel, the Aargauer Kunsthaus in Aarau, the Kunsthaus in Zürich, and the Kunstmuseum in Bern.

[3] For lack of a better formulation, this expression encompasses populations from the MENA area, South and Central America, India, and Asia.

[4] Kunstmuseum Bern stands apart as it is the only Swiss museum to have organized several group shows, 11 since 2005 to be precise, focusing on the artistic production of a non-western area: China, South and Central America, Mexico, South and North Korea, India.

[5] Statistics based on the data available on each museum’s websites in July 2022. The collection of the Kunstmuseum Bern is not accessible online and therefore not included in the present study.

[6] Rasheed Araeen (1935) 3 artworks; Siah Armajani (1939-2020) + 20 artworks; Mohammed Bourouissa (1978) 2 photos; Stanley Brouwn (1935-2017) 9 artworks; Frédéric Bruly-Bouabré (1923-2014) 1 artwork; Geraldo de Barros (1923-1998) 1 artwork; Augusto de Campos (1931) 1 artwork; with Julio Plaza 2 artworks; Silvie and Chérif Defraoui (1932-1994) 5 artworks; Alfredo Jaar (1956) 1 artwork; Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige 3 artworks; Hayan Kam Nakache (1982) 9 artworks; David Lamelas (1946) 1 artwork; Ken Lum (1956) 1 photo; Karim Noureldin (1967) 1 artwork; J.D.’Okhai Ojeikere (1930-2014) 3 photos; Mai-Thu Perret (1976) 11 artworks; Sarkis (1938) 64 artworks; Hassan Sharif (1951-2016) 2 artworks; Sada Tangara (1984) 1 photo; Hervé Télémaque (1937) 1 artwork.

[7] Kader Attia (1970) 3 artworks; Renée Green (1959) 2 artworks; Lubaina Himid 1 artwork; Alfredo Jaar (1956) 1 artwork; Anish Kapoor (1954) 1 artwork; Nalini Malani (1946) 1 artwork.

[8] Silvie (1935) and Chérif Defraoui (1932-1994) 2 photos; Karim Noureldin (1967) 1 artwork; Mai-Thu Perret (1976) 4 artworks; Taiyo Onorato (1979) and Nicolas Krebs (1979) 3 sets of photos; Shirana Shahbazi (1974) 1 artwork; Fiona Tan (1966) 1 artwork.

[9] According to the federal administration, in 2021, 39 percent of the permanent resident population has a migration background. See: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population/migration-integration/by-migration-status.html

[10] During museum night, museums remain open throughout the night and charge no admission, drawing large crowds.

Photo by Marie-Laure Allain Bonilla: Lubaina Himid, A Fashionable Marriage, 1984-1986, installation detail. Exhibition view of the artist’s solo show Lubaina Himid: So Many Dreams at the Musée cantonal des beaux-arts (MCBA), Lausanne (2022-2023).

Published on February 21, 2023.