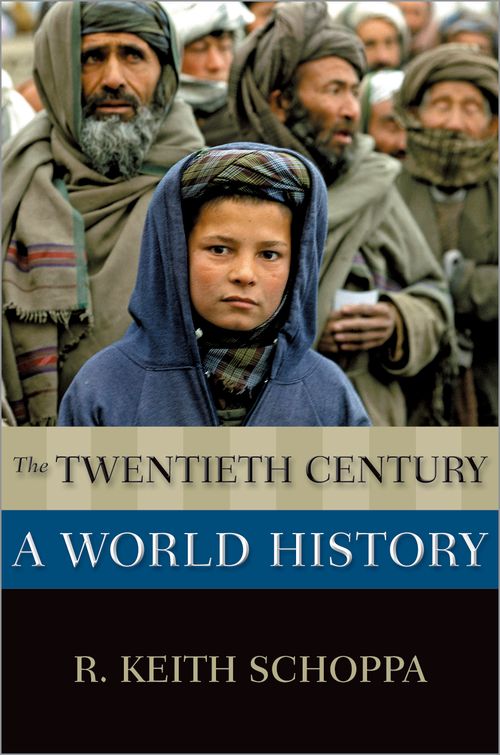

The twentieth century was an age of promise and advancement as well as of destruction. It entailed leaps in life expectancies, literacy rates and scientific knowledge. It included advancements in the status of women and many minority communities, albeit uneven. And it birthed human rights as we understand them today. It also engendered ideological extremism and the most destructive military conflicts the world had ever seen. Following a long-twentieth century narrative, moreover, the era is bookended by genocides. R. Keith Schoppa’s The Twentieth Century: A World History addresses the period from 1900 to the present, in its extremes of progress and tragedy and, remarkably, it condenses a sprawling global narrative into a succinct 175 pages.

Because of how concise it is, the book, which can be used as a textbook, cannot cover the entirety of the world and the century and makes no pretension to do so. Rather, The Twentieth Century is chronologically and thematically organized into chapters that deal with major global trends: The Great War and Social Change; Totalitarianism and the Great Depression; Revolution, Cold War, and Decolonization. Methodologically, Schoppa adopts a tri-focal lens through which he analyzes the individual/local, the nation-state, and the global. His intervention stands out as it highlights the glocalization and compression of the last century along the themes of genocide, warfare, and refugees.

Each chapter is set up along similarly chrono-thematic lines. This organization allows for sweeping and unconventional discursive threads that push students to think beyond conventional geographical and national restrictions. For instance, the chapter “A New Day? Revolution, Cold War, and Decolonization, 1950-1965” takes the reader from Francis Crick’s discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA and the eradication of polio to Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward and the anticolonial conflicts in Malay, Kenya, Indochina, and Algeria, to the Civil Rights movement in the United States and the apartheid regime in South Africa. The chapter then shifts to a brief account of the Suez Crisis, which, following a postwar narrative of challenging prewar structures, opens into a discussion of the global influence of the Beat writers, Elvis Presley, and the Beatles. Schoppa does all of this before a concise meditation on the significance of the Second Vatican Council for the “new day” that seemed to be unfolding. Admittedly, for the instructor, such sprawling narratives make it challenging to lecture on one single chapter at a time. However, when used to provide a thematic backbone to more pointed concept-oriented units rather than lecture material, The Twentieth Century proves the value of Schoppa’s approach. Even when a lesson involves issues traditionally associated with the nation-state, it introduces students to some of the wider historical changes in which those issues are embedded, opening discussions not only to national peculiarities but also to trans- and international connectivity.

What is more, Schoppa’s expeditious approach to relating history allows him to intervene in important historical discussions without laboriously rehashing old arguments or diving too deeply into historiographical issues. Although advanced undergraduate and graduate classes might need to resort to heavy auxiliary readings to fill in some of those historiographical gaps, instructors of introductory history courses will likely receive Schoppa’s pacing favorably. For example, his discussion of the Soviet-Afghan War centers on Anahita Ratebzad, a feminist reformer and member of the Afghan Politburo. As Schoppa explains, she served not only in a Soviet-sponsored government but also “as a bridge from the Afghan communist regime to progressive regimes outside the Soviet bloc” (121). When reading the stories of Ratebzad and the regression in women’s rights that followed the Soviet withdrawal, students must grapple with the ambiguities of a situation that cannot be reduced to simple tropes of oppressive Soviet invaders and noble native resistance. Such a reading of 1980s Afghanistan may not be everything a student should know about the conflict, but it does offer a welcome counter to the conventional narrative that reduces the conflict to Soviet overreach and decline. In doing so, it introduces complicated issues of women’s rights in South Asia, the ambiguities of humanitarianism, and the appeal of Soviet communism in the Global South despite its cruelties.

Another strength of the book is its truly global emphasis, which decenters the US from the narrative without ignoring the outsized role it played in global affairs. Rather than a history of America or the West in the world, this is a history focused on colonialism and anticolonialism, on a century of both progress and mass atrocity. In a depth rarely reached elsewhere in the book, Schoppa dedicates the entire introduction to the genocide committed against the Herero and Nama peoples of German Southwest Africa (modern Namibia). He concludes the book with a chapter that examines both the triumphs of the 1990s—the end of apartheid, the Israeli-Palestinian peace process (which seemed to be making strides at the time), and scientific advancements, including computers and advances in DNA science. It also examines the calamities that occurred in the 1990s, such as the Yugoslav Wars and the Rwandan genocide. He then pivots to Myanmar and Aung San Suu Kyi, once the global face of the struggle for human rights in Bangladesh, then complicit in the Rohingya genocide. Hence, not only does Schoppa evade any discussion of September 11—admittedly, a strange omission—but he skillfully draws the narrative up to the present day through an important and complex story unfamiliar to many students.

The Twentieth Century is not without its limitations. In interpreting the century as an age of fracture and violence first and advancement second, it paints an especially dark picture of the recent past and present. Much of this is justified. However, if one chooses to use this as a textbook, I recommend that it be complemented with readings that balance out the disillusionment that comes through on nearly every page. Per Schoppa, The Twentieth Century is dedicated to relating this history in all its warts (and worse) in order to “transform the spirit of this century” into one that values human rights, coexistence, and the fragile environment that still keeps us thriving as a species. Supplemental sources that bring light to how these values existed in and persisted throughout the twentieth century might also offer clearer direction on how to achieve that end and add levity and hope to Schoppa’s rather bleak account. Despite these minor drawbacks, this is a potent and provocative book that will likely make an impact in any collegiate class that adopts it.

Today, the themes of violence, ethnic cleansing and genocide of the twentieth century are regrettably timely in a modern history course as the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfolds. Pulling Ukraine into lessons can make for some lively discussions about the ways in which the last century, as well as our own, continues to bear the imprint of the history of past genocides, WWI and WWII, the continued prominence of the nation-state and the persistent problem of nationalism, which need to be examined with those predecessors in mind.

Nicholas Ostrum received his PhD in History from Stony Brook University in 2017. He is currently a lecturer at Xavier University of Louisiana and has been a member of EuropeNow’s Research Editorial Committee since the journal’s inception. His research examines West German petrorelations with key petroleum producers of the emerging postcolonial world.

The Twentieth Century: A World History

By R. Keith Schoppa

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Paperback / 192 pages / 2021

ISBN: 978-0190497361

Published on February 21, 2023.