An introduction to our special feature, United in Diversity.

“United in diversity” is the official motto of the EU. Yet, this special issue appears at a moment when European unity seems distant, and diversity seems to foster disunion, conflict, and cultural clash, rather than accord. We may do well to recall that the motto reaches back to the immediate post-WWII era and the attempts to overcome the cataclysm of the war. The effort to forge a new foundation for the continent turned against the nationalist imperialism that had led the world down paths of horrific death and terrible destruction—twice. A quest for a common cultural foundation led to heady discussions that generated the Cultural Resolution at the close of the Congress of Europe.[1] And that resolution led to the formation of the European Centre for Culture in Geneva.[2] Calls ensued from these gatherings for a federation of European Universities “to facilitate the co-ordination of scientific research into the condition of twentieth-century European,” a common forum for the advancement of European cultural producers understood broadly, support for the youth coming of age in the rubble of the war, and a common cultural and spiritual education that would form a new citizen of a new Europe.[3] Eighty years later, the quest for an appreciation of European diversity confronts real hard differences in memory and legacies of historical conflict. The Great Recession and the Eurozone crisis highlighted how regions and nations had diverged economically, and the responses showed a lack of European solidarity or common concern for the social welfare of those on the streets in one’s own country, let alone those forced onto the streets in other countries. Where in the early days of the Post-war European Movement the quest for a European subject based in a common commitment to universal human rights seemed to provide a foundation for unity, the contemporary EU led project of unionization shifted the focus onto the diversity of nations, regions, and locales has challenged the harmonization of Europe with an at times essentialist particularity. Citizens’ rights and human rights seem at times to draw apart.

In this context, across the continent, discussions of European diversity diverged from discussions of multiculturalism, a term that has often been associated with Europe’s post-war migrant populations.[4] To be sure minority groups and diverse voices have made great strides in gaining recognition and advocating for inclusive societies; yet as a response to the contemporary backlash against gender and sexual minorities, Black Lives Matter and #MeToo protests in Europe reveal that those gains are tenuous and not universal.[5] We recall that in 2010, considering migration to Germany from Turkey and the Muslim world in general, conservative Christian Democrat Chancellor Angela Merkel declared multiculturalism as failed.[6] She stepped forward at that moment as a leader of a broad movement that sought to close the Schengen zone borders to migrants from the Southern Mediterranean, indicted generations of European inhabitants for a failure to integrate, and bolstered a nationalist agenda for increased sovereignty. A few short years later, however, Merkel had lost that leadership position to voices from the further right. She and other European establishment politicians confronted the rise of populist parties attacking her and her colleagues for being soft on immigration. Gathered in the European Parliament, those anti-EU populists excoriated the EU for a democracy deficit that kept it distant from the real needs of the EU’s half billion citizens. And in its most vocal formation, the Brexit campaign succeeded in the once unthinkable, bringing a core EU member state to leave the Union on the basis of xenophobic, anti-EU, nationalist rhetoric. In these developments, an Identitarian movement emerged that advocated for the diversity of Europe as an attack on Europe’s multicultural diversity. Regionalism and heritage threatened to become bulwarks from which attacks on Europe’s ethnic, religious, racial, and sexual minorities could take place. A European unity formed out of a rejection of the European Union.

Yet, as much as the news cycles are dominated by reports of discord, we can observe the rise of movements to express an even more ardent and impassioned longing for European union. Millions march on London, Bratislava, Bucharest, Paris, Berlin, and Brussels, calling for more union. A youth schooled in the Erasmus programs—a community of cultural producers formed through a common European network of festivals, workshops, and centers—European coalitions of activists joined to confront violent injustice and spreading fascistic lures—elderly former refugees themselves reaching out to those forced across Europe’s borders–children skipping school to demand a climate policy that assures them of a future. These communities all meet on the streets, in the institutions, and through the social media of Europe. They call us to live up to the best of European political and ethical aspirations; they call us out to be our better selves.

Perhaps it brings us hope for the future of Europe and our collective future to recall that the long history of Europe has been one of a dynamic of cultural dis/Union. And indeed, in that history of conflict, we find some of the most memorable expressions of European unity. We find models of unity in diversity that help us find hope in the present and inspiration for our future.

This special issue of EuropeNow contains contributions exploring European cultural diversity and difference. It offers analyses of historical conflicts and moments of regional divergence. It considers various forms of expression: film and literature, monuments and installations, performance and image.

In “Coming to Terms with Controversial Memories in South Tyrol: The Monument to Victory of Bolzano/Bozen,” Andrea Carlà and Johanna Mitterhofer take on questions of regionalism and nationalism in one of the territories marked by shifting borders and language politics. Exploring the history of the Monument to Victory of Bolzano/Bozen, a white marble arch built by the Fascist regime in South Tyrol, they present a positive model of heritage that allows us to rediscover the conflictual places of the past as a common public sphere in the present.

Zakaria Fatih takes up a different history, that of the “Vichy syndrome” in France. In “The Institutional Denial in French Political Historiography,” Fatih discusses a recent French debate of the historians, driven by Henri Rousso’s The Vichy Syndrome. The analysis explores how the focus on the resistance in occupied France has excluded an interrogation of the extensive collaboration during the period. Fatih, however, brings the discussion into a broaderproblem of unresolved anti-Semitism and unexplored colonial legacies. He describes a condition of historical selective memory that rends contemporary France into dominant and minority community.

In “Reinventing European History to Show that Black Lives Do Matter: The African Presence in Europe within an African Diasporic Paradigm,” Lydia Lindsey and Carlton Wilson provide a pedagogical foundation for a single course or a full curriculum that counters the dominant narrative of European history. The essay makes a case for a greater complexity of European history that starts from a proposition of Eurafrica as a continuous space with a common history. The project here refuses a narrative of geographic discontinuity of “here” and “there,” and an easy distinction of a colonial “us” and “them.” The analysis shows that requiring a real engagement with centuries of violence and disruption does not preclude a real informed ability to celebrate cultural production.

Giovanni Dettrori explores how the imagined community of the nation actually suppresses other imaginative communities. “Regional Identity in Contemporary Sardinian Writing” considers especially the work of Sergio Atzeni (1952–1995), whose multivalent novels negotiate local particularities and transnational universals.

In “Drawing Difference: Representing Franco-Arab Culture in Halim Mahmoudi’s Arabico and Un Monde Libre,” Jocylen Wright turns our attention to the graphic novel series Arabico. The discussion allows us to recognize the serious work of a French-Maghrebi cartoonist. Wright helps us consider the images but also the context of their production and the limitations Mahmoudi experienced in negotiating the band desinee market. It points to the difficulties of anti-racist work in France and the problems of positioning to which artists with a migrant background are exposed.

In “Colours of a Journey: An Archive of Human Mobility” Senka Neuman Stanivukovic, and Katerina Anastasiou, a duo of academic and migration activist, engaged in the transform!europe initiative consider the efforts of Colours of a Journeyto develop an archive of the contemporary migrants. They explore CoJ as a representative of other initiatives in archival design and practices. And they provide insight into concrete practices around children’s education to help the very young record their own experiences in a condition of human mobility.

Daniel Shea takes us to a different frontier of Europe little-considered in the current considerations of migration. In his article “Boxed In: Minority-Authored Films of Assimilation in an Irish Context,” he reminds us that there is no region of Europe not impacted by complex histories of immigration and emigration. Focusing on a short film with potential to go viral, Shea describes a project that does not pit a cultural center against a resistant minority pushing against the encroachment of Irish homogeneity. He considers how this project presents a collaborative reproduction of the immigrant experience and refuses to “put you in a box” as one character tells another.

In “Shedding Waters: Cinematic Mediations of European Multiculture,” Matthew Miller offers up a possibility of representing European space that counters mapping practices dominant since the nineteenth century project of nation-building began. He explores how the contemporary films Les Alsaciens ou les Deux Mathilde (Favart 1996) and Eldorado (Imhoof 2017) provided a hydrocentric mapping of Europe and European culture. Miller considers how these films, a decade apart, offer important models of thinking diversity and cultural difference in European space.

In “Survival within Survival in Ayşe Toprak’s Mr. Gay Syria (2017),” Ljudmila Bilkic reminds us that the borders of European cultural expression and political engagement are not limited by the Schengen Borders of the EU. Bilkic explores the complexity of European production and support for the film Mr. Gay Syria, while simultaneously attending to the particularities of the images in the films. She helps us understand how the film reveals the potentials of people confronting “modern rapid migration.”

Tom Haakenson takes on the controversy around Ai Weiwei’s recent work while himself in exile in Berlin. “The Refugee Affect: Ai Weiwei in Berlin” parses out carefully and precisely the way that Ai Weiwei was positioned as a world-renowned artist and framed himself as refugee while in Berlin. Haakenson helps us understand the controversy sparked when Ai Weiwei was photographed in the position of the drowned body of Aylan Kurdi. Ai Weiwie sought to replace the iconic body of the drowned child with his own body sprawled out on a rocky beach. Mediated communication and artistic expression are Ai’s familiar terrain but Haakenson helps us understand why the celebrated artist could flip so quickly to a condition of repudiation in the press.

These essays ask us to attend to European specific models of diversity and difference. Although the models of multiculturalism and inclusion that US activists and academics advocate have in some ways obtained a preeminent position in discussions of diversity and difference, they actually often fall short in the face of European formations. The great “melting pot” of the US is itself a radically different context than the European “united in diversity.” We do well to attend to how European cultural diversity and difference arises out of a complex connectivity of nation and region, formed themselves by imperial and colonial legacies. Europe is an interzone of languages, dialects, ethnicities, and religions, informed by heartfelt conflicts. The special issue presents Europe as a place where the dialectic of in/tolerance and dis/union has inspired vibrant cultural expression and powerful political activism.

In bringing this collection of essays to press, Gisela Brinker-Gabler and I want to thank a number of colleagues who helped with comments and editing: Anke Biendarra, Kristin Dickenson, Lina Insana, John Lyon, Dana Och, David Pettersen, Sabine von Dirke.

Randall Halle (Klaus W. Jonas Professor of German Film and Cultural Studies) is the Director of the Critical European Culture Studies Program at the University of Pittsburgh. His books include The Europeanization of Cinema and Toward a Transnational Aesthetic.

Research

- “Drawing Difference: Representing Franco-Arab Culture in Halim Mahmoudi’s Arabico and Un Monde Libre” by Jocelyn Wright

- “Reinventing European History to Show that Black Lives Do Matter” by Lydia Lindsey and Carlton Wilson

- “Boxed In: Minority-Authored Films of Assimilation in an Irish Context” by Daniel Shea

- “Regional Identity in Contemporary Sardinian Writing” by Giovanni Dettori

- “Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West: Invisible Borders and the Exclusion of Refugees” by Nurettin Ucar

- “The Refugee Affect: Ai Weiwei in Berlin” by Thomas O. Haakenson

- “Survival within Survival in Ayşe Toprak’s Mr Gay Syria (2017)” by Ljudmila Bilkic

- “Coming to Terms with Controversial Memories in South Tyrol: The Monument to Victory of Bolzano/Bozen” by Andrea Carlà and Johanna Mitterhofer

- “Shedding Waters: Cinematic Mediations of European Multiculture” by Matthew D. Miller

- “The Institutional Denial in French Political Historiography” by Zakaria Fatih

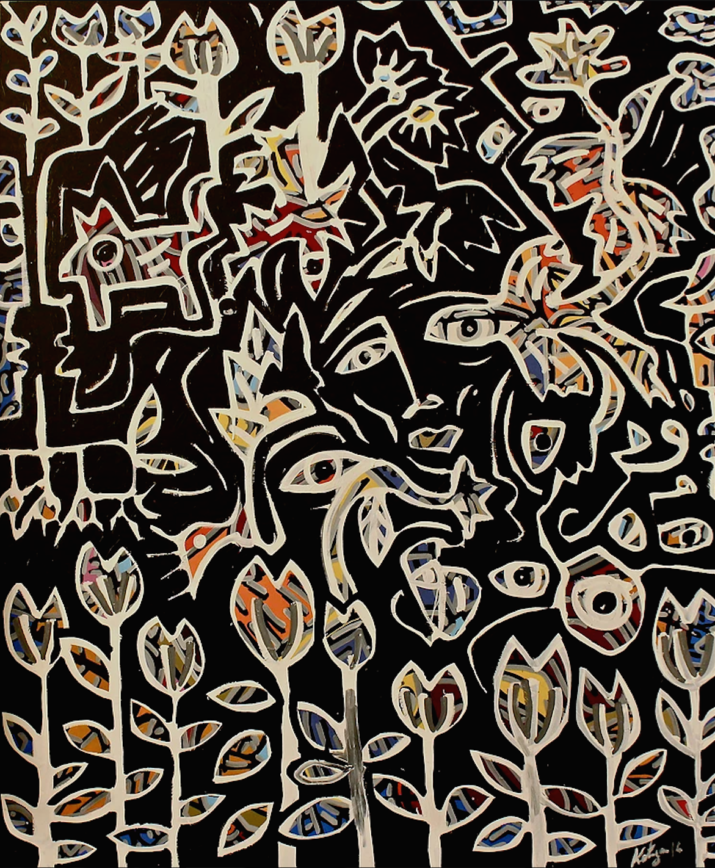

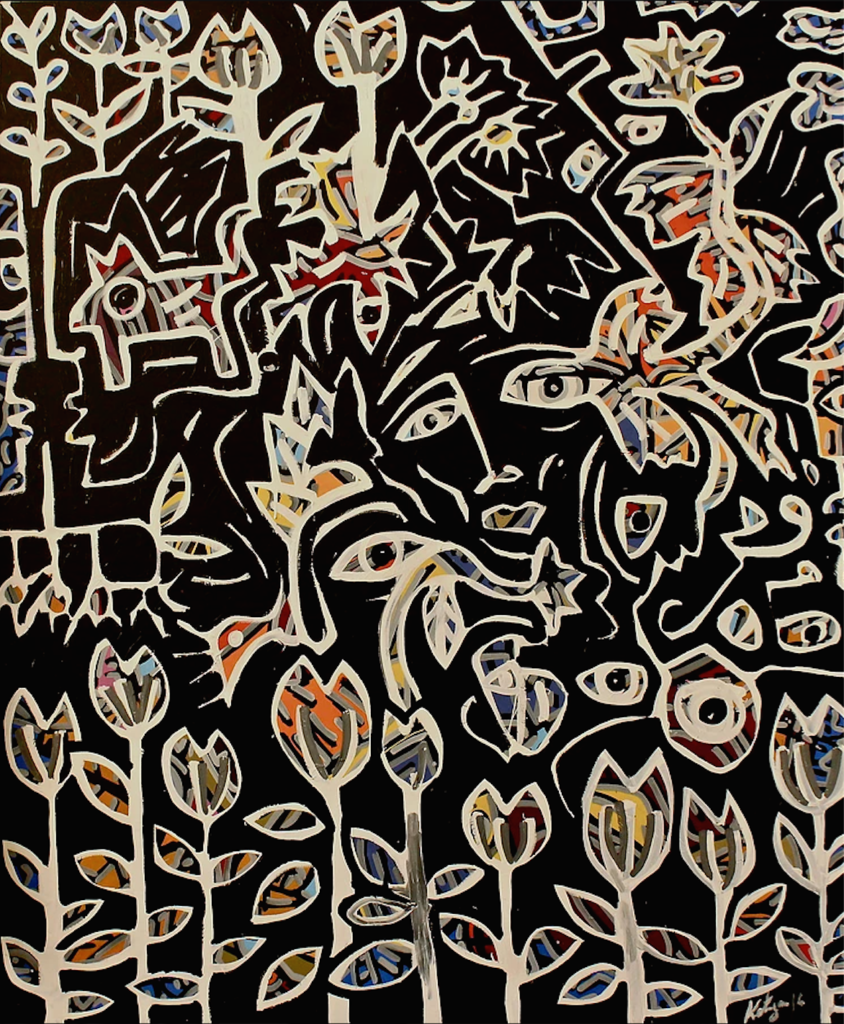

Visual Art

The Daily

References

Chalmers, Damian, Markus Jachtenfuchs, and Christian Joerges. The End of the Eurocrats’ Dream. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

“Cultural Resolution of the Hague Congress (7–10 May 1948).” In Congress of Europe: The Hague-May, 1948: Resolutions, 16. London-Paris: International Committee of the Movements for European Unity, 2012. https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/cultural_resolution_of_the_hague_congress_7_10_may_1948-en-f9f90696-a4b2-43fd-9e85-86dee9fb57a5.html.

Fuchs, Dieter, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann. Cultural Diversity, European Identity and the Legitimacy of the EU. Studies in EU Reform and Enlargement. Edward Elgar, 2011.

Guibernau i Berdún, M. Montserrat. Governing European Diversity. Governing Europe. SAGE, 2001.

“Programme et Objectifs de La Conférence Européenne de La Culture (1949),” July 9, 2012. Mouvement européen. ME 528. Archives historiques de l’Union européenne. https://www.cvce.eu/en/collections/unit-content/-/unit/04bfa990-86bc-402f-a633-11f39c9247c4/46688a91-795c-463e-8428-8160936e3752.

Taras, Raymond. Challenging Multiculturalism:

European Models of Diversity, 2012.

[1] “Cultural Resolution of the Hague Congress (7–10 May 1948).”

[2] “Programme et Objectifs de La Conférence Européenne de La Culture (1949).”

[3] “Cultural Resolution of the Hague Congress (7–10 May 1948),” 16.

[4] Fuchs and Klingemann, Cultural Diversity, European Identity and the Legitimacy of the EU.

[5] Chalmers, Jachtenfuchs, and Joerges, The End of the Eurocrats’ Dream; Guibernau i Berdún, Governing European Diversity.

[6] Taras, Challenging Multiculturalism.

Published on April 5, 2019.