Drawing Difference: Representing Franco-Arab Culture in Halim Mahmoudi’s Arabico and Un Monde Libre

This is part of our special feature, United in Diversity.

In the opening pages of Halim Mahmoudi’s graphic novel Arabico (2009), a young boy leaves his apartment to buy bread for his mother. As he walks down the street, a police car pulls up and two officers stop him to ask where he is going. When the boy responds, truthfully, that he is going to buy bread, the officers glare at him with doubtful, narrowed eyes before driving off to hassle the next young boy they see on the street. The boy is safe, for now. As he continues on his way, a woman waiting at a bus stop who saw the event laments that the police are stopping all the young Arab boys they encounter in the neighborhood.

Young Arab men just like the boy in Arabico are a group that continues to be maligned in France due to a complex combination of colonial history and socioeconomic class. Algeria was a former colony of France, and this colonial past, followed by the painful and violent decade-long war of decolonization in the 1960s and the second Algerian Civil War in the 1990s, have created stereotypes of Algerians as violent.[1] In recent decades, they have increasingly been associated with terrorism due to events such as the Civil War, the Khalid Kelkal bombings in 1995, the attacks on the Charlie Hebdo headquarters in 2015, and the November 2015 attacks in Paris.[2] These events have all resulted in an environment of profound distrust in which the Arab other is feared. French media and popular culture in the past two decades have reinforced these fears with post-apocalyptic narratives of a France controlled by the Muslim Brotherhood (Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission) and banlieue crime dramas where ethnic strife and drug abuse are at the center (Pierre Morel’s Banlieue 13).

Graphic narratives like Arabico are an attempt to push back against these dominant narratives by stressing the right of persons of Arab origin to belong in and be considered part of France. Comics are a particularly interesting medium with which to address these questions because they require the author to make choices about physical representations of their characters, including their markers of racial or religious differences. Although Franco-Belgian comics have had a complex relationship with race (see, for instance, early Tintin), French alternative comics have pushed back against stereotypical and racist representations of multiethnic characters since the late 1970s.[3] Today, especially in France, where official policy discourages differentiating citizens on the basis of race or ethnicity, comics are a subversive tool for pushing back against stereotypes.

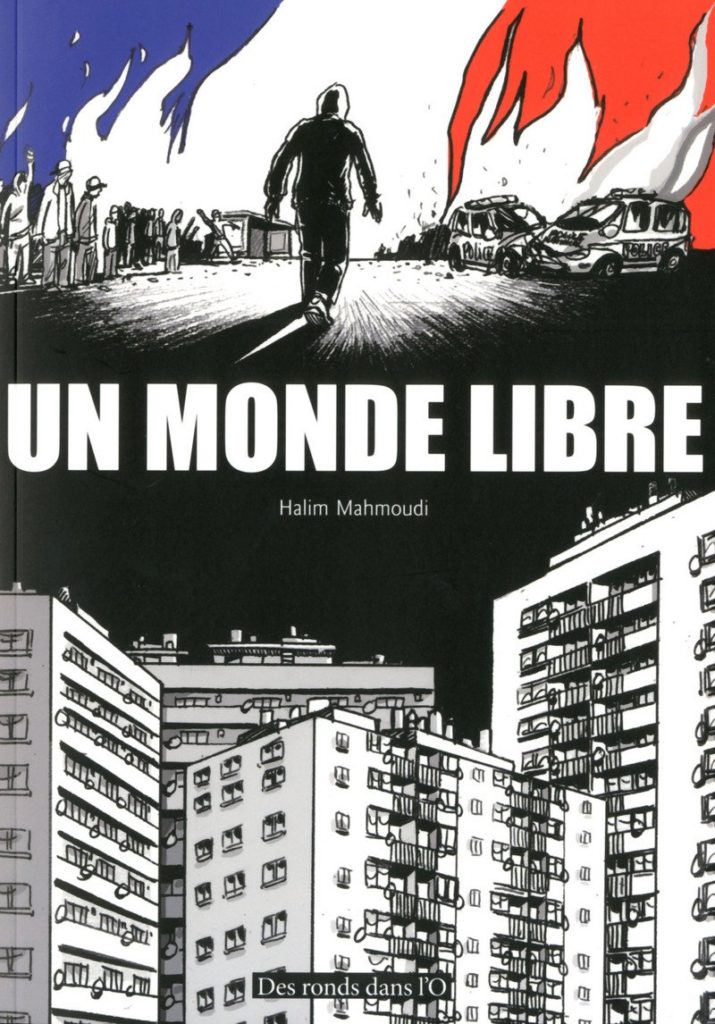

Mahmoudi is a French citizen born to Algerian parents who grew up in a cité in Oissel, outside of Rouen. Though he describes his culture as “Muslim,” he himself is not religious.[4] He studied design at the École supérieure d’art et de design at Amiens, then moved to Quebec for three years where he worked as an editorial cartoonist. Mahmoudi is one of the many contemporary graphic novelists who uses his work to push back against stereotypical representations of Arabs and Muslim culture. Mahmoudi describes bande dessinée as “un langage universel qui s’adresse à tout le monde” (“a universal language that speaks to everyone”), and he has used the universal quality of this medium to address questions of race, religion, and identity in both Arabico Tome 1: Liberté (2009) and Un monde libre (2014).[5] Mahmoudi published Arabico, his first comic book, with Les Éditions Soleil, a major publishing house and the only large, minority-run comics publishing house in France.[6] Arabico was initially conceived as a three-part series, titled “Liberté,” “Égalité,” and “Fraternité,” (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity — the national motto of France) but due to slow sales, only the first two volumes were published. In 2014, in lieu of a creating a third volume of Arabico, Mahmoudi featured the same protagonist from Arabico in a graphic novel, Un monde libre, which he published with Des ronds dans l’O, a smaller publishing house. While Mahmoudi’s approach in Arabico was to make a story about racism and identity accessible to children, in Un monde libre, he took the opposite approach, creating a graphic novel that addressed these same themes in an alternative format aimed at adults.

Arabico

Identity is a central theme in Arabico, since the protagonist (who is given no name in the story) does not know if he is French or Arab. In spite of his birth in France, he feels a connection to his Arab origins and is not sure how to bring these two identities together. The innocent question, “Where am I from?” becomes a fully-fledged identity crisis when he loses his identity card and becomes convinced that he is a “sans-papier” (illegal immigrant) who must hide from the police. He becomes increasingly scared of the police and, when he is approached by a police van, he runs away from it. When the police catch him, they assume that he stole a car and bring him directly to the station for aggressive questioning. When he doesn’t speak, and cannot produce identity papers, the police, assuming he is an illegal immigrant, taunt and brutally beat him. Although he is eventually saved by his family, the protagonist’s encounter with police brutality rips away his childhood innocence, making him realize that he cannot trust the very institutions of power that were, ostensibly, in place to protect him.

Arabico takes these complex concepts— identity, race, racism, police brutality — and places them within the uniquely French context of classic Franco-Belgian comics. These topics are rare in any French comic book, and, especially, in comics aimed at children. Other serialized Francophone comics with minority protagonists, such as Téhem’s Malika Secouss or Manu Larcenet’s Nic Oumouk, tend to eschew any sustained engagement with the difficulties minorities encounter, from police violence to questions about their identity and their feeling of belonging in France. Texts that do deal with these themes at great length, such as Gilles Rochier’s TMLP or Julien Revenu’s Ligne B are marketed only to a smaller, adult audience.

Accessibility and broad commercial appeal was at the forefront of Mahmoudi’s mind when he created Arabico. At forty-eight pages, the typical length for a serialized album, Arabico is short enough to read in a single sitting. Mahmoudi said he wanted to write an affective story that appealed to readers’ sense of humanity. He also sought to publish Arabico with a big publishing house so that it was accessible to a wide audience.[7]

Arabico is drawn in a bright, commercial style with clear influences from the Franco-Belgian comics tradition, which began with Bécassine, the classic young Breton housemaid and one of the first French comics characters. Bécassine was always drawn with a round face, a rounded nose, and bright red cheeks, and this style was mimicked in numerous Franco-Belgian comics, including Tintin, Spirou, Fantasio, Gaston Lagaffe, and Les Schtroumpfs. Mahmoudi’s stylistic choice to follow in this tradition is doubly interesting since many early Franco-Belgian comics, especially Tintin, have been critiqued for the stereotypical ways in which they represented minority characters (see, for instance, Tchang Tchong-Jen in Le Lotus bleu).

By visually aligning his story with that of the greater Franco-Belgian comics tradition, Mahmoudi is highlighting his characters’ French identity. At the same time, he celebrates his protagonists’ Algerian culture, not only by portraying him in the traditional fez and djellaba [1] [2] he wears on the cover page, but also by dressing him in the red, green, and white of the Algerian flag throughout the story. Mireille Rosello’s work on stereotypes asks us to consider not only how we can push back against stereotypes, but also to ask, “What can I do with a stereotype?”[8] Mahmoudi’s artistic style in Arabico exemplifies one way problematic stereotypes can be manipulated into subversive artistic output by reclaiming a space that previously excluded portrayals of complex minority characters and giving the Arab, black, and Jewish characters in his voice a rich backstory and significant roles in the story.

Mahmoudi uses every element of Arabico, from the title to the speech bubbles,as an opportunity to reframe Arab culture in a positive light. (Because of this, the comic can also be read as a continuation of a long line of ethnographic novels written by francophone Algerian writers, from Mouloud Feranoun to Mohammed Dib in the 1950s and 60s.) The title Arabico comes from the protagonist’s baby sister mispronouncing his nickname, “l’abricot.” She calls him “l’arabico,” a term which recalls “bicot,” a pejorative French term for persons of Maghrebi origin. By transforming this racial slur into a diminutive, and making it the title of his text, Mahmoudi makes it clear that his intention is to, likewise, challenge and distort our stereotypes of Arabs. The album’s first page immerses the reader in a world of brown speech bubbles, which is striking since speech bubbles in comics are nearly always white. Many of these speech bubbles are filled with transliterated Arabic expressions which are translated in footnotes at the bottom of the page, making the space even more Arab. By including these Arabic expressions and phrases, the album is also serving a didactic purpose of introducing the reader to a culture and language with which they might not otherwise be familiar.

Un Monde Libre

Although he never got the opportunity to make the third volume of Arabico, Mahmoudi continued to explore the same themes of identity and racial discrimination for a different, adult audience. Un monde libre’s longer length, experimental structures (full pages that make up a single frame and large portions of narrative text presented outside the speech bubbles), black-and-white composition, and overt images of violence and sexual activity make it clear that the book is not intended for children.

Mahmoudi has said that the differences between Arabico and Un monde libre were meant to reflect the way the protagonist, whose name in Un monde libre is Khalid, becomes more self-aware of not just himself, but also his position in the world and how that is influenced by a long and complex history of exploitative colonization.[9] While Arabico relates only the highly subjective and personal experience of one small child’s quest for identity, Un monde libre places this individual quest within a larger social, political, and economic context. If the little boy in Arabico thinks the answer to the question of who he is can be reduced to whether he is French or Arab, Khalid has both accepted his dual identity as French and Arab and is set on understanding both the place from which he comes and the political, social, and economic dynamics that brought his family to France.

Mahmoudi treats the same themes of police brutality, violence, colonization, and its after-effects in France with considerably more vitriol in Un monde libre than he did in Arabico. In Arabico, the lingering after-effects of France’s colonial past with Algeria are present, but only as subtle background images. For instance, in one scene, Arabico’s protagonist waits at a bus stop called “17 octobre” for the #61 bus, named Papon, a clear reference to the massacre of Algerians in Paris, where many Algerians peacefully protesting the war were thrown into the Seine River by a police force captained by Maurice Papon on October 17, 1961.[10] These references, however, are not significant to the plot and thus are more like Easter eggs for colonial history buffs than opportunities to explore this complex history. By contrast, the colonial context that brought about events such as the Seine massacres is the focus of Un monde libre. The book opens with the immigration story of Khalid’s parents, and, later, the reader follows Khalid’s trip back to Algeria to visit his family. There is copious imagery of the Seine Massacres, from the iconic “Ici on noie les Algériens” (“One drowns Algerians here”) signs to images of the protestors calling for peace in Algeria.[11]

Mahmoudi further critiques the way that history, and particularly the history of colonization, is taught in France because it casts colonization in a positive light and ignores the suffering it caused the Algerian people.[12] In another episode, Mahmoudi takes the reader back to the colonial exhibitions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century where Africans were literally displayed in cages for white French people to gawk at. He relates the story of a little girl who goes with her mother to the fair and encounters a young boy in a cage.[13] While the man running the fair and the little girl’s mother tell her to keep her hands away from the cage, she reaches her hand out and holds the hand of the boy, and, in that moment, she imagines them not just as friends, but as lovers. (This teases the present-day love story between Khalid and his white, French wife.) The perspective of a young child adds to the emotional impact of the story, while the imagined love story acknowledges the reality that there are many mixed-race couples in France today.

Colonial Contexts

In an interview, Mahmoudi lamented that colonial history, and the experiences of discrimination and social marginalization that are its inevitable byproducts, are largely experienced in isolation. Mahmoudi says when he was growing up these topics were neither discussed between friends or his Algerian family members, nor acknowledged by government institutions. Due to this silence, Mahmoudi says he was frustrated that he never knew whether the difficulties he had experienced as a young child in France were specific to him or part of larger systemic problem.[14] Both Arabico and Un monde libre were intended as correctives to this silence.

Mahmoudi’s two attempts to fill this silence were met with different results. Despite Mahmoudi’s best efforts to make Arabico appealing to a wide audience, the series was a commercial failure and both albums are now out of print. Unfortunately, Arabico’s commercial failure is reflective of larger conditions within the market for bande dessinée (French comics). Comics with minority protagonists are rarely commercially viable in France. Mourad Boudjellal, who runs the Soleil publishing house that published Arabico, has lamented that portrayals of North African working-class characters, even from well-respected and celebrated creators have much less broad commercial appeal than genres like heroic fantasy.[15] While Arabico’s efforts to bring a minority character into the comics mainstream were unsuccessful, Un monde libre, which did not have the same aspirations towards universality, found greater success in its niche environment. The opening pages of the graphic novel were exhibited at the Musée national de l’histore de l’immigration in France and are now part of the museum’s permanent collections.

Following Un monde libre, Mahmoudi shifted gears yet again and tackled an entirely different subject. His newest graphic novel, Petite Maman (2017), recounts the abuse of a young girl at the hands of her violent step-father, and how that young girl helps herself and her mother to get out of this situation. The shift away from narratives about race and discrimination is not uncommon for contemporary French-Algerian authors, many of whom, like Mahmoudi, go on to tell stories that may not even feature characters of Arab origin. This shift, is, perhaps, the most important, as it cements these artists’ positions, not only as voices in a debate about immigration and identity, but also as artists whose primary motivation is, and has always been, to tell a great story.

Jocelyn Wright

has published several articles and book chapters on immigration, identity, and

race in contemporary French and Francophone novels, films, and graphic novels.

Most recently, she published “Transnational Bande Dessinée in the 21st Century:

An Introduction” in the International

Journal of Comic Art. She has a forthcoming book chapter on banlieue film in

Screening Youth: Contemporary French and Francophone Cinema with

Edinburgh University Press, expected in May 2019. She holds a PhD in French

Studies from the University of Texas at Austin.

References

Bowen, John. Can Islam be French?: pluralism and pragmatism in a secularist state. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Falcon, Karl. “Des Racines et Des Bulles.” AlgerParis 4 (Juillet-Août 2014): 94-95.

Golsan, Richard J. “The Papon affair: memory and justice on trial,” ed. Richard J. Golsan, trans. Lucy B. Golsan and Richard J. Golsan. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Hargreaves, Alec. “Muslims and the Middle East.” Contemporary French Civilization 40, no. 2 (2014): 235-54.

Laurence, Jonathan and Justin Vaisse. Integrating Islam: political and religious challenges in contemporary France. Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2006.

Mahmoudi, Halim. Arabico, Tome 1: Liberté. Paris: Quadrants Soleil, 2009.

Mahmoudi, Halim. Interview by

Coline Bouvart. BDZoom.com, November 27 2009.

http://bdzoom.com/6348/interviews/rencontre-avec-halim-mahmoudi/. Mahmoudi, Halim. Interview by Dee Brooks. “De l’intime au collectif.” La Nouvelle Vie

Ouvrière (September 2014): 19.

Mahmoudi, Halim. Interview by Kenza Sefrioui. Tel Quel, March 2015.

Mahmoudi, Halim. Interview by Sceneario.com. Sceneario.com, October 2009. http://www.sceneario.com/interview/halim-mahmoudi-pour-arabico-tome- 1_ARABI.html.

Mahmoudi, Halim. Interview with Antoine Chosson, Vincent Marie, and Yvonnick Segouin. Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, November 2013. http://desrondsdanslo.blogspot.com/2013/11/entretien-avec-halim-mahmoudi-un- monde.html.

Mahmoudi, Halim. Un monde libre. Paris: Des ronds dans l’O, 2014.

Stora, Benjamin. Algeria 1830-2000: A Short History. Translated by Jane Marie Todd. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

McKinney, Mark. “Framing the Banlieue.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 8, no. 2 (2004): 113-126.

Rosello, Mireille. Declining the Stereotype: Ethnicity and Representation in French Cultures. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1998

[1] See, among others, Benjamin Stora, Algeria 1830-2000: A Short History, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001); Jonathan Laurence and Justin Vaisse, Integrating Islam: political and religious challenges in contemporary France (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2006); John Bowen, Can Islam be French?: pluralism and pragmatism in a secularist state (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010)

[2] According to Alec Hargreaves in “Muslims and the Middle East,” Contemporary French Civilization 40, no. 2 (2014): 236, “Since the 1990s, new actors have come to the fore: young men from Muslim immigrant families who have grown up in France, small but growing numbers of whom have engaged in acts of terrorist violence within and outside the hexagon linked to the politics and religions of the Middle East.”

[3] Mark McKinney, “Framing the Banlieue,” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 8, no. 2 (2004): 113.

[4] Halim Mahmoudi, interview by Sceneario.com, Sceneario.com, October 2009. http://www.sceneario.com/interview/halim-mahmoudi-pour-arabico-tome-1_ARABI.html

[5] Quoted in Karl Falcon, “Des Racines et Des Bulles,” AlgerParis 4 (Juillet-Août 2014): 94.

[6] McKinney, “Framing the Banlieue,” 114.

[7] Halim Mahmoudi, interview by Kenza Sefrioui, Tel Quel, March 2015)

[8] Mireille Rosello, Declining the Stereotype: Ethnicity and Representation in French Cultures (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1998), 13.

[9] Halim Mahmoudi, interview by Dee Brooks, La Nouvelle Vie Ouvrière, September 2014, 19.

[10] For a brief introduction see, among others, Benjamin Stora, Algeria 1830-2000: A Short History; Richard J. Golsan, “The Papon affair: memory and justice on trial,” ed. Richard J. Golsan, trans. Lucy B. Golsan and Richard J. Golsan (New York: Routledge, 2000).

[11] The phrase refers to graffiti that was drawn along the banks of the Seine following the Seine Massacre, and was also the title of a recent documentary by Yasmina Adi released in 2011. An image of the graffiti has become a metonym for the entire massacre, which was, until quite recently, the subject of much official silence.

[12] Halim Mahmoudi, Un monde libre (Paris: Des ronds dans l’O, 2014), 30.

[13] Mahmoudi, Un monde libre, 49-50.

[14] Halim Mahmoudi, interview by Sceneario.com, Sceneario.com, October 2009.

[15] McKinney, “Framing the Banlieue,” 114-115.

Published on April 5, 2019.