This is part of our special feature, United in Diversity.

How to assemble, curate and circulate an archive of human mobility? The Colours of a Journey (CoJ) is a collective that addresses these questions by envisioning an archive of human mobility that apprehends the variegated practices and experiences of movement. Assemblages of people on the move (but also regimes that attempt to govern them), are ephemeral and defined by difference, multiplicity, and contradiction, as opposed to sameness, unity, and consensus. However, this multiplicity and contradiction is often left unrecognized and silenced by the existing archival contents and forms, narratives, and borders of the European political project in general, and European border and citizenship regimes in particular.

A discussion of the ongoing and envisioned activities of the Colours of a Journey to create an archive of human mobility offers a possibility to critique the knowledges about migratory movements produced by European institutional structures including Frontex by juxtaposing them to for instance the experiences, practices, and memories articulated by the migrants themselves through mediums such as drawings, photography or performance. At the same time, by thinking through CoJ, one can also ask new questions about what are archives, how are they figured and refigured, and for what purpose especially against the backdrop of multiple and far-ranging translocal spaces that are imagined and enacted through human mobility. More specifically, by linking the practices of the CoJ collective to a more abstract notion of a dissenting archive, we are would like to explore how texts and visual artifacts such as images or films can, in their own right, be agents of resistance by interrupting the established order and consequently opening up the potential for alternative possibilities – hence, thinking, imagining and doing otherwise.

Archives are sites of contested knowledges.[1] To understand how political power is reproduced and challenged through particular representations of human mobility and stay in relation to for instance citizenship, it is key to question how archives are made, maintained, and refigured (hence, what and how it is being recorded, assembled, ordered, or transmitted). At the same time, one’s goal should be broader than that. The CoJ can provide an example on how to overcome the established positions about the meaning and location of an archive and proper ways of record-keeping. It can serve as a platform for a discussion on and a search for archival praxis and design that are able to record varied events (and non-events) of human mobility, and in which everyone, in many places, and across different time-periods can become an archivist.

As such, the CoJ repeats the calls of many artists, activists, and scholars to visualize, map, and narrate the uneven geographies and temporalities of migratory movements and – by arguing from the standpoint of migrants – to counter the simultaneous securitization and humanitarization of migrants by EU policies and political discourses.[2] Through the gaze of the subsequently produced counter-visualities, counter-narratives, and counter-cartographies of migration, one witnesses how (not only) the European political order is displaced and reassembled in relation to the scattered practices of human mobility to become a reactionary and diffused “apparatus of capture.”[3]

In this way, an archive becomes more than a tool for ordering the past to structure collective consciousness and discipline societies. It is also more than an attempt to expose and trouble these dominant orders through recording, memorializing, and reproducing varied everyday experiences and practices of the public. The CoJ projects an archive as an active arrangement of the materialities and affective work of sound, text, and image that concurrently structures political subjectivities, defines agency, and opens up potential for resistance. It helps us imagine and problematize an archive that, rather than imposing boundaries on the political sphere, transcends these boundaries to uncover what stands beyond the common sense. Such an archive is an open site that connects what is commonly known and recognized with those knowledges and sensibilities that are not apprehended and unrecognized to counter the established structures of power and create new connections between people, places and times.

Dissenting Archive and Children’s Drawings

Our thinking is grounded in the efforts of Colours of a Journey to develop archival design and practices to record events and experiences of human mobility, and to transmit these records trans-locally in a way in which everyone, in many places and across time-periods, can become an archivist. This may create a space where migrants can voice their own experiences, stories, and expectations.[4] Both authors of the text have been active members of the CoJ collective since its start in 2016. This is also the reason why we hope to use this text to map the existing and envisioned activities and challenges of CoJ to create a trans-local archive of human mobility. Through its past and approaching actions, CoJ illustrates how an archive can respond to the absences and misrepresentations of migrant stories (especially of migrant children) in mainstream discourses and migration records, and how mobilization of the images through artistic/artivist interventions into public spaces and digital platforms and practices can create new modalities of co-presence and shift the boundaries of the possible.

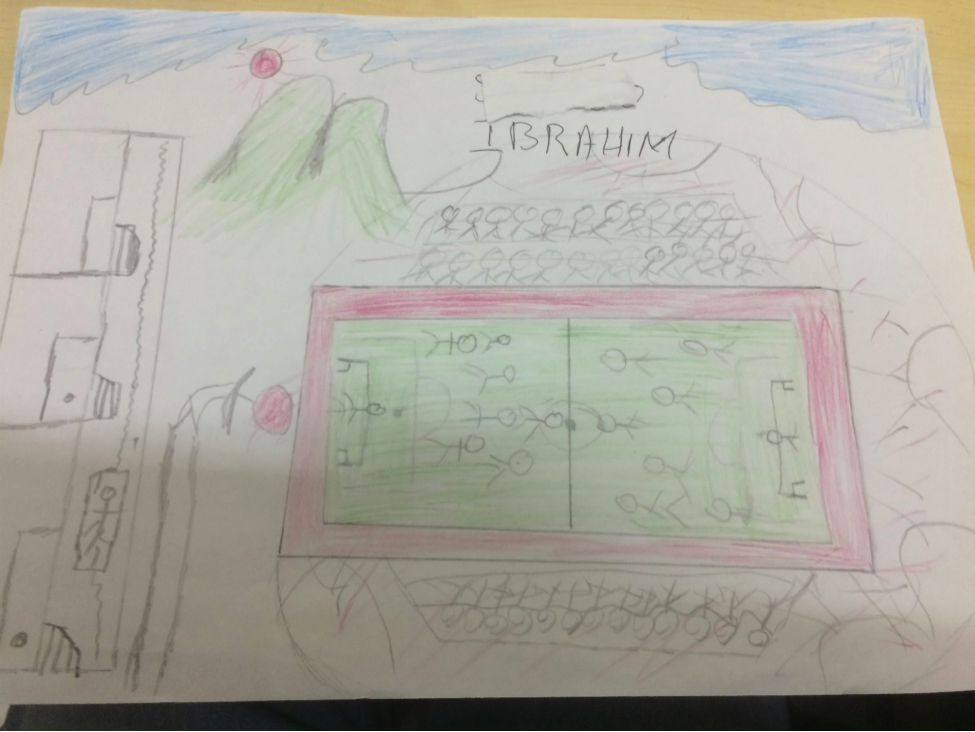

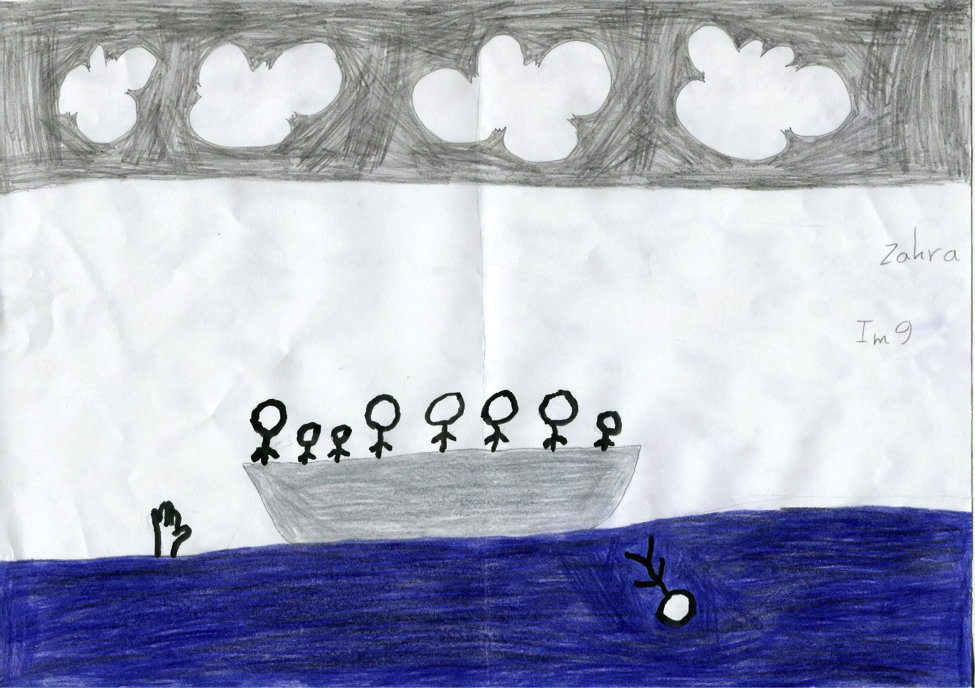

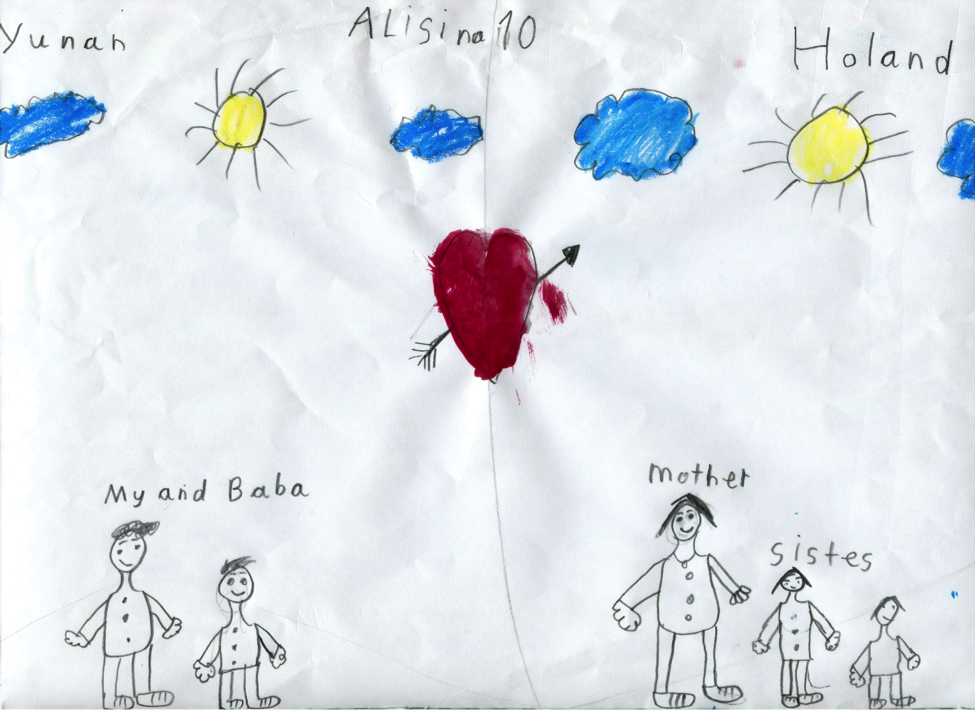

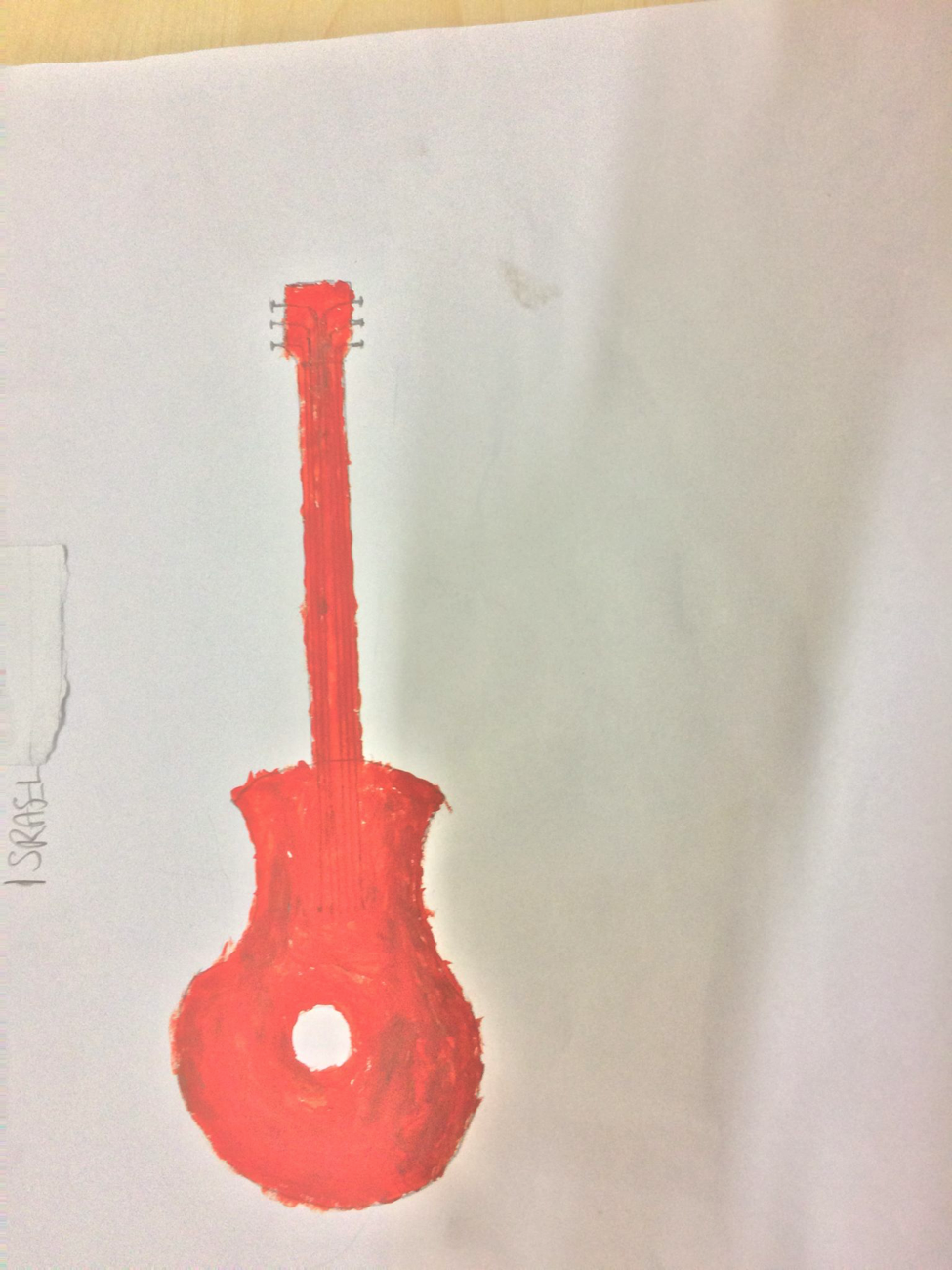

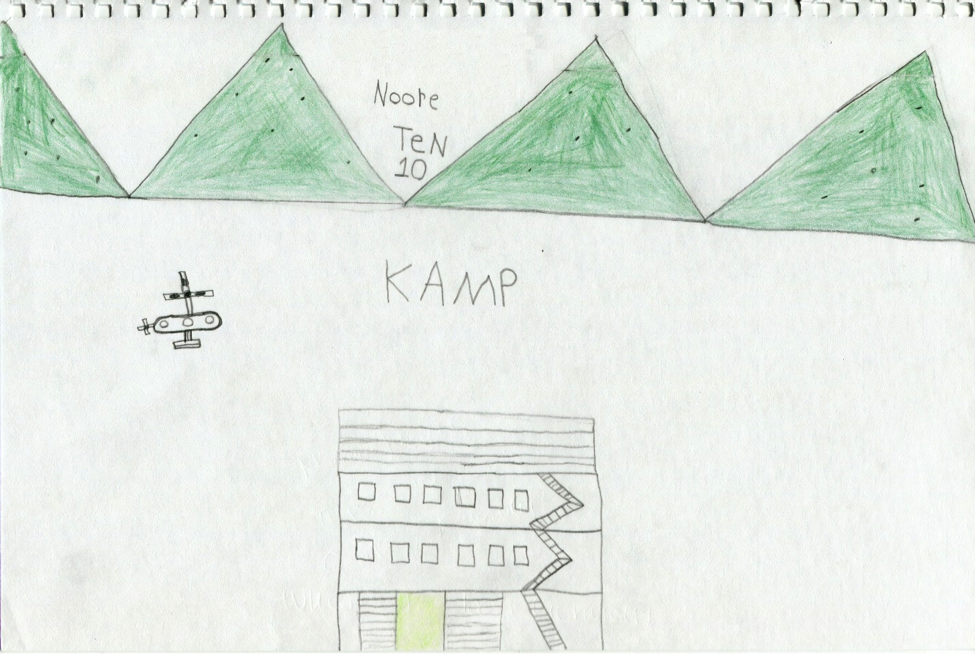

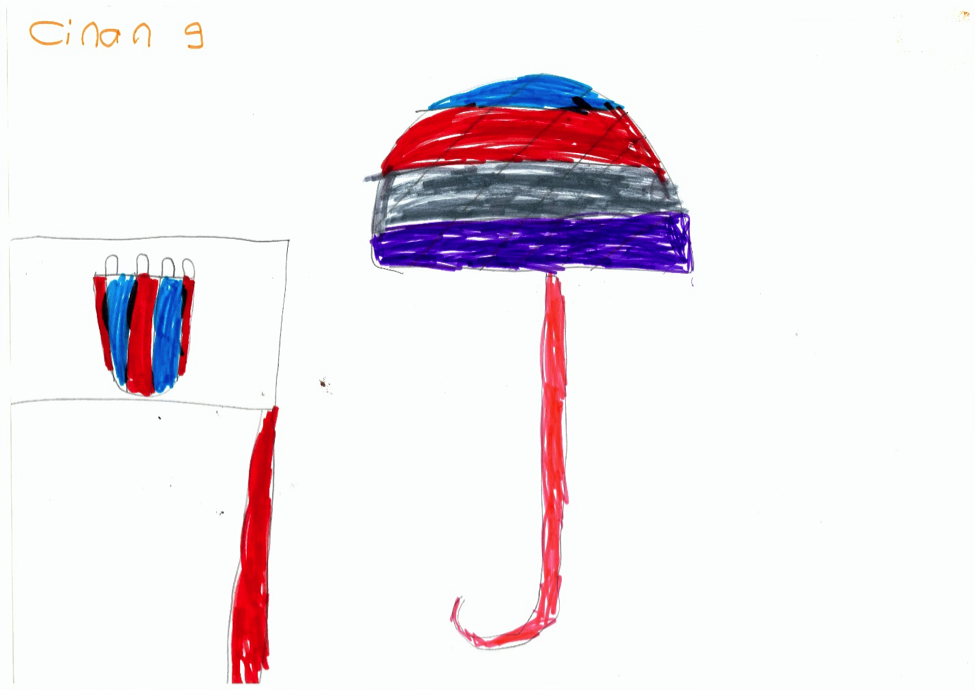

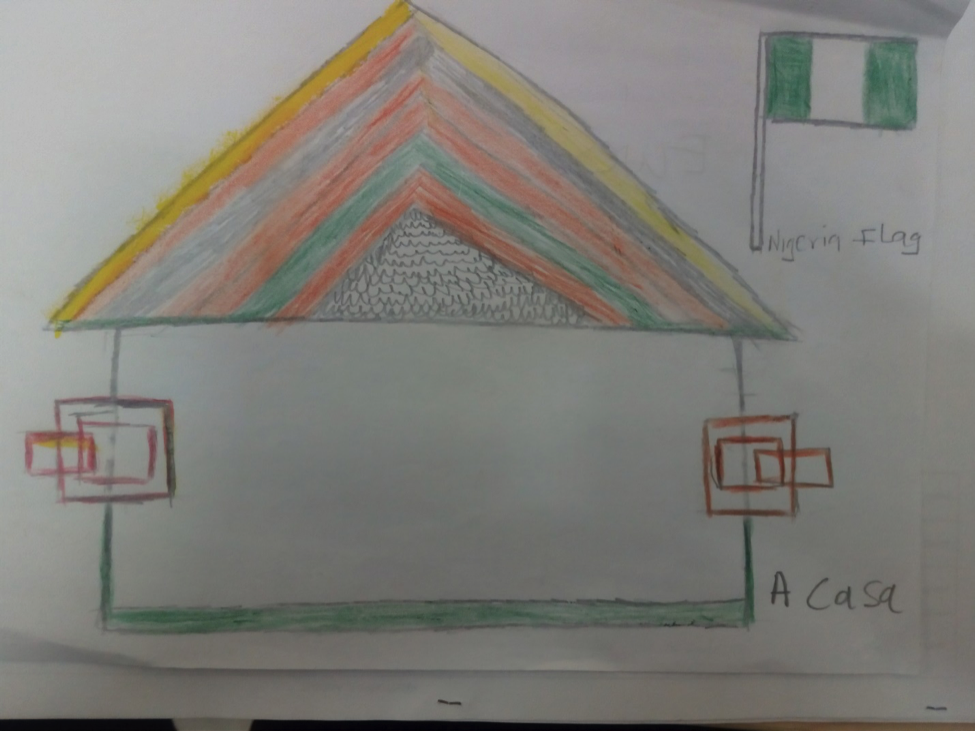

Its past activities have focused on collecting and circulating drawings of migrant children, which have illustrated how the concurrent politics of fear and of a humanitarian spectacle deny children any agency as their stories are silenced. The drawings testify to the varied experiences of migration and, through the unique representations of migratory journeys, challenge and reimagine particular certainties about the institutional, spatial, and temporal conditions that define the European political project. Currently, CoJ plans to expand its scope of action to – with artists and artivists of migrant backgrounds – co-collect and co-create visual (re)productions of migration, particularly graphic and lens-based images including drawings, photographs and mobile phone films. Furthermore, it will train migrant communities and migrant solidarity structures in DIY documentation, mapping and archiving technologies and techniques to support more grounded records of migratory strategies and experiences, while being committed not to expose, harm and endanger these communities.

Colours of a Journey was inspired by an exhibition organized by Italian civil society ARCI network and displayed during the Sabir Festival of Cultures in 2016.[5] The exhibition included a series of drawings made by unaccompanied children who survived the horrific shipwreck close to Lampedusa island in 2014. The children told their stories by illustrating their past, present, and future. Colours of a Journey has continued working very closely with both ARCI and the Sabir Festival to implement a similar format in a series of workshops with refugee and migrant children across Europe. Since 2017, we have held workshops in close cooperation with local solidarity structures in Greece, Italy, Croatia, and Portugal. We have also organized multiple exhibitions, symposia, and public gatherings where these drawings were exhibited across Europe.

The archive is collected and circulated in three steps. In the first step, CoJ continuously maps and maintains contact with migrant solidarity structures across Europe including the EU. These structures participate in the CoJ platform as partners.[6] We try as much as possible to avoid parachuting into the everyday routines of the children to extract information. This is why the workshops are organized in cooperation with local structures that maintain close and regular contact with migrant children. Usually, the workshops are incorporated into the daily leisure or learning activities of the children. We also do not work with a generic format of the workshop, and each event is designed to support the specific needs and contexts of the individual groups. To illustrate, the Elliniko camp workshop took place within deteriorating and provisional conditions of an old airport hangar.[7] The number of children attending the workshop exceeded our capacities as well as those of the provided infrastructure, and we owe the success of the workshop to one artist resident of the camp and a group of older children who volunteered to facilitate the drawing activities. We were unable to maintain contact with the children as Elliniko was emptied shortly after the workshop took place. In Croatia, the workshops were facilitated by the NGO Udruga Balkon in the reception centers Hotel Porin and Kutina as part of a border scope of children’s educational activities.[8] A similar format was followed by ARCI in Italy. In Portugal, Catapulta is developing a workshop that brings together migrant and refugee children with children experiencing various other forms of marginalization.

In the second step, the drawings are collected, organized, and uploaded to the CoJ platform.[9] We make sure that the anonymity of the children is protected, while, at the same time providing the children with a sense of ownership over their drawings. Many of the drawings are signed with the child’s first name and occasionally have some accompanying text. If a surname is provided, we do not make this visible. On the platform, the drawings are organized into several categories based on, first, the child who made the drawing (i.e. country of origin, country of residence, desired destination) and, second, the theme of the drawing (i.e. past, present, future). At the same time, these categories are transcended by the varied representations of the children’s migratory movements and everyday lives in the drawings. Motives such as schools, houses, desired professions, or expressions of belonging through state flags or football club emblems are shared across several workshops.

At the same time, there are large differences between the drawings from individual workshops, making visible the varied nature of migratory movements and conditions in individual reception centers.

In the third step, Colours of a Journey, in cooperation with partners across Europe, organizes a series of exhibitions and other forms of interventions into public and political discourses on migration. All entries to the archive are open-access under the creative commons license. The drawings were shown and articulated in discussions in various places including museums, public libraries, university spaces, human rights, and cultural festivals, public parks and activist spaces, they were included in a literary publication Letters to Europe, and we are currently finalizing a series of visual materials that document and problematize the viewers’ engagement with the drawings.[10] In the curation of the exhibitions/interventions, we have attempted not to over-narrate the drawings by (among other things) making sure that varied experiences and depictions of migration are visible in the given event.

How to Archive and for What Purpose?

It is hard to imagine an archive of complex conditions, experiences, and perceptions of human mobility that cannot (and should not) be enclosed by various state archives or recording practices of multiple regimes, which attempt to displace, govern, and create hierarchies among people on the move through various binaries, including the citizen/alien or asylum-seeker/irregular migrant. Our effort to think about such an archive in terms of difference (as oppose to sameness) as an organizing principle of the social and political does not make it less puzzling. We approach this task by exchanging the daunting question of what an archive is with an inquiry into the practice and purpose of archiving in solidarity with people on the move.

Our point of departure is Rancière’s work on democratic politics as dissensus. Rancière defines politics as an inherent tension between order that conditions what is possible to perceive, think and do within a collectivity on the one hand and disruptions of this order by those that are excluded (made insensible and inexistent) from the collectivity on the other.[11] Stoler has recently translated this discussion to the case of a Palestinian archive where she conceptualizes archiving as a dissenting practice.[12] She envisions archiving as a practice that is attentive to objects that can act as sites of contention and contradiction and have the potential to establish new connectivities, even if these objects are subtle or may appear irrelevant to struggles in countering the commonly accepted truths and histories. Similarly to Stoler, we hope to locate an archive in disorder to acknowledge the subversive and creative potential of attending to the varied experiences and practices of human mobility. More precisely, we explore how individuals, by recording their everyday experiences and practices, can disrupt the unquestioned “truths” about the European socio-political order. As such, CoJ offers an interesting intervention into the academic discussions about representations of migration and the transmissions of memories of migration. It demands that migrants themselves record their struggles in a liberating way and beyond the boundaries of the national discursive and institutional orders, while also attempting to locate the emergence of new political subjectivities in these struggles. It focuses on how images including drawings and photography can be utilized as material mechanisms that interrupt the established order of domination and reconstruct new social and political relations. This makes CoJ also boldly political because it refuses to reduce the archive to often simplistic and clichéd discourses of inclusion, representation, and agency, aiming instead to develop a new language and typologies of documenting and archiving migration around disagreement.

What is more, for us, to archive does not mean to deposit the past – therefore, to concurrently preserve and cancel. We hope to rethink an archive as an arrangement that defines political possibilities for the future by reordering the past, but even more so an arrangement that disturbs the ordering of time into a single narrative of the past, present, and future including classifications of particular occurrences as events and post-events while sidelining other as non-events. This refers to the creation of new archives as well as to the re-claiming of existing state records to expose spatial and temporal complexities of migratory journeys and stays and to suspend the dominance of records that construct migration as a linear progression towards the West. In that sense, CoJ challenges the efforts to subsume the variegated geographies and temporalities of migratory movements into a single teleology of becoming European. As such, it opens up the potential for recognizing migrant subjectivities beyond the European/non-European and citizen/non-citizen binaries. We echo the already established critiques of the Fortress Europe metaphor and the representation of the European border and migration regimes as unified, solid, and territorially grounded.[13] The uneven geographies of migration spaces disrupt and challenge the simplistic EU/non-EU binaries; by documenting migrants’ strategies to access and reclaim spaces that they have been deprived of, it becomes obvious that “crossing” the Schengen border is not a singular act that ends the migratory journey equally as representations of migratory movements as linear journeys into Europe oversimplify their multifaceted nature.

Moreover, European policies and political discourses on migration position Europe and the process of becoming European as the standard through which the spatial and temporal characteristics of migratory journeys are noticed and judged. Simply put—migratory movements become problematized only once they reach Europe and are then presented as a linear process that culminates with entering the European shores. This is however quite far from reality. The geographies of migratory movements are more complex than what is made to seem by, for instance, the so-called Western Balkan or the Mediterranean route discourses. Also, migrants’ perception of time contradicts the idea that migration is a linear movement (in)to Europe. Migration includes (not only) periods of transit and periods in waiting; it connects past histories of the spaces along the route with contemporary migrant experiences and practices. Not only are complexities of postcolonialism or postsocialism made invisible by the dominant representation of migration as a progression to Europe, but also the figure of the migrant becomes overdetermined by the struggle for “Europeanness.” CoJ troubles these reductionist representations by showing how migration exposes various spatial and temporal forms of domination and resistance that escape the imaginary frontiers between what is seen as liberal, democratic, and progressive North/West and the underdeveloped and backward South/East.

Dissenting Archive and Variegated Europe

European migration crisis discourses and associated governance practices stretch the figure of a migrant on a spectrum between a migrant-threat and a migrant-victim, consequently attempting to stabilize the European political order through the dual spectacle of border militarization and humanitarization. European migration management consequently produces and governs migratory movements through the simultaneous politics of criminalization (also of smuggling) and deportation of migrants on the one hand and the construction of migrant vulnerabilities and politics of rescue on the other. In the context of the multiple European “crises” discourses and governance practices, mobility, as an act that decenters the established European socio-political order(s) including border and citizenship regimes, is re-stabilized through the creation of mobile and fluid military-humanitarian border assemblages that simultaneously monitor, channel and prevent migrant movements.[14]

What becomes apparent, nonetheless, is that, despite the invested efforts of various European and national political actors and technocratic bodies to locate Europe within the particular demarcated space and time, and along a defined self-other binary, a unified political narrative or a homogenous political order that would bring together multiple geographies and temporalities produced in the context of migration governance is lacking. The EU’s Agenda on Migration or Frontex risk analysis reports call for a Common European Asylum System and the protection of the common external border against the threat of irregular migration.[15] However, the Mediterranean or the Balkans are more than crossings and frontiers of Europe. In the migration context, these become spaces of struggle that destabilize the imaginary that encloses Europe into a fixated institutional architecture, geographical borders and temporalities of European integration.[16] We see the children’s drawings and the particularities of the articulated multiple pasts, presents and futures in the CoJ archive also as such spaces of struggle.

CoJ interrupts and transcends the clichéd divide between a stable and prosperous Europe and instable and backward geographical and temporal “others,” and opens up the potential for thinking about Europe through the prisms of multiplicity and disorder. Whereas the drawings still represent a journey, or more precisely a multiplicity of them, the established picture is much messier than a story of a linear move to Europe. The drawings represent the journeys as concurrent times of (violent) transit, displacement and waiting, as well as of conducting everyday routines such as playing football, attending school or playing the guitar.

Spatially, the drawings relocate Europe in multiple geographies of passage, camps, and deportations that exist in between the child’s country of origin and a place of desired destination. These “archipelagos” of migrant (im)mobilities that come in various shapes and forms blur the distinction between (EU) order and (non-EU) disorder. The drawings destabilize Europe in scattered geographies of migrant mobilities (and presence). They also appropriate spaces such as camps through which mobilities are re-territorialized and governed. The concurrent politics of care and protection and the politics of detention that are made possible by the creation of (not only) refugee camps as zones of suspended or limited mobility are reclaimed by the expressions of everyday activities, friendships and new senses of belonging, but also of radical hope that emerge from the drawings.

The temporal “scapes” in which the journeys unfold also challenge the manifold political and policy attempts to stabilize Europe in “times of crisis” and “times of normalcy.” The drawings illustrate silenced and enduring uncertainties and insecurities that stand outside of the “crisis” designation. They also challenge the understanding of migration as linear unfolding of time spent on entering Europe. The idea that migratory movements are defined by a singular event of a “refuge” that ends in a mixture of a hospitable and hostile encounter with the asylum laws, practices, and infrastructures of Europe and upon which migrants are either welcomed into or denied access to Europe collapses in the stories told by the drawings. In this regard, particularly interesting is the blurring of temporal categories of the past, present and future in some of the drawings; at times the same or a similar house would be flagged by a child as both past and future, or the representations of violent sea crossings would be merged with depictions of life in the reception centers under the category present.

In line with the above, we would like to see Colours of a Journey develop into a practice of future-making through dissenting archival work. In the context of human mobility, this means more than democratizing access and giving agency to those with migration experiences. In that sense, CoJ, next to being a grassroots, non-institutional and somewhat rogue exercise, is also determined not to tell a unified story or give a clear picture because it sees significant political potential in disorderly and dissenting archiving.

Katerina Anastasiou is a migration activist and the facilitator of the chapters Migration and Global Strategy in transform!europe. Her focus is militant organizational practices and communication. She is active in various grassroots groups in Austria and Europe. She is an active member of the Colours of a Journey collective.

Senka Neuman Stanivukovic is an assistant professor in European Studies at the University of Groningen. She researches contestations to institutional and political Europeanization in South East Europe and the post-Soviet spaces at the intersection of work, human mobility and social protest. She is an active member of the Colours of a Journey collective.

References

Balibar, Étienne. “Borderland Europe and the Challenge of Migration.” Open Democracy 8 (2015): 1-7.

Casas-Cortes, Maribel, Sebastian Cobarrubias, Nicholas De Genova, Glenda Garelli, Giorgio Grappi, Charles Heller et al. “New Keywords: Migration and Borders.” Cultural Studies 29, no. 1 (2015): 55-87.

Colours of a Journey. “Colours of a Journey.” Accessed March 20, 2019. https://coloursofajourney.eu/

Colours of a Journey. “Structures.” Accessed March 20, 2019.

Associazione Ricreativa e Culturale Italiana. “Chi Siamo – Storia.” Last modified, June 10, 2018. https://www.arci.it/chi-siamo/storia/;

European Commission, A European Agenda on Migration, COM(2015) 240 final, Brussels, 2015.

FutureLab Europe. “Letters to Europe – Female Refugees Telling Their Stories.” Accessed March 20, 2019. https://futurelabeurope.eu/2017/03/23/letters-to-europe-female-refugees-telling-their-stories/

Garelli, Glenda, Alessandra Sciurba, and Martina Tazzioli. “Introduction: Mediterranean Movements and the Reconfiguration of the Military‐Humanitarian Border in 2015.” Antipode 50, no.3 (2018): 662-672.

Hamilton, Carolyn, Verne Harris, Jane Taylor, Michele Pickover, Graeme Reid and Razia Saleh, eds. Refiguring the Archive. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002.

Josip Miličević. “Život u Porinu.” MAZ, June 1, 2017. http://www.maz.hr/2017/01/06/zivot-u-porinu/

Rancière, Jacques. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010.

Sabir – Festival diffuso delle culture mediterranee. “Edizione 2016 – Il Programma dell’ Edizione.” Accessed March 20, 2019. https://www.festivalsabir.it/edizione-2016/

Scheel, Stephan. “Recuperation through Crisis Talk: Apprehending the European Border Regime as a Parasitic Apparatus of Capture.” South Atlantic Quarterly 117, no. 2 (2018): 267-289.

Stoler, Ann Laura “On Archiving as Dissensus,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 38, no.1 (2018): 43-56.

[1] Carolyn Hamilton et al. eds., Refiguring the Archive (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002).

[2] See for instance initatives such as Atlas of Borders, Spaces of Migration and Storie migrant.

[3] Stephan Scheel, “Recuperation through Crisis Talk: Apprehending the European Border Regime as a Parasitic Apparatus of Capture,” South Atlantic Quarterly 117, no. 2 (2018).

[4] Within the broader scope of human mobility, CoJ focuses particularly on the migration experiences of those whose mobility and access to particular spaces has been restricted by European citizenship, asylum and border regimes.

[5] “Chi Siamo – Storia,” Associazione Ricreativa e Culturale Italiana, last modified, June 10, 2018, https://www.arci.it/chi-siamo/storia/; “Edizione 2016 – Il Programma dell’ Edizione,” Sabir – Festival diffuso delle culture mediterranee, accessed March 20, 2019, https://www.festivalsabir.it/edizione-2016/

[6] “Structures,” Colours of a Journey, accessed March 20, 2019, https://coloursofajourney.eu/structures/

[7] “Inside the Refugee Camp of Elliniko,” AthensLive News, October 28, 2016, https://medium.com/athenslivegr/inside-the-refugee-camp-of-elliniko-b592d31f4630

[8] Josip Miličević, “Život u Porinu,” MAZ, June 1, 2017, http://www.maz.hr/2017/01/06/zivot-u-porinu/

[9] “Colours of a Journey,” Colours of a Journey, accessed March 20, 2019, https://coloursofajourney.eu/

[10] “Letters to Europe – Female Refugees Telling Their Stories,” FutureLab Europe, accessed March 20, 2019, https://futurelabeurope.eu/2017/03/23/letters-to-europe-female-refugees-telling-their-stories/

[11] Jacques Rancière, Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010)

[12] Anna Laura Stoler, “On Archiving as Dissensus,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 38, no.1 (2018).

[13] Maribel Casas-Cortes et al., “New Keywords: Migration and Borders,” Cultural Studies 29, no. 1 (2015).

[14] Glenda Garelli et al., “Introduction: Mediterranean Movements and the Reconfiguration of the Military‐Humanitarian Border in 2015,” Antipode 50, no.3 (2018).

[15] European Commission, A European Agenda on Migration, COM(2015) 240 final, Brussels, 2015.

[16] Étienne Balibar, “Borderland Europe and the Challenge of Migration,” Open Democracy 8 (2015).

Published on April 2, 2019.