Translated from the French by Janet Louth.

It seems to me that the people sitting at tables on the terraces notice me in spite of my shabby clothes.

Once a woman sitting behind a tiny tea-pot eyed me from head to foot.

Happy and full of hope, I retraced my steps. But the customers smiled and the waiter looked at me hard.

For a long time I remembered that unknown woman, her throat and her breasts. I undoubtedly pleased her.

When I was in bed and heard midnight striking, I was sure she was thinking about me.

Oh, how I should love to be rich! Everyone would admire the fur collar of my overcoat, especially in the suburbs. My jacket would be open. A gold chain would hang across my waistcoat; my purse would be attached to my braces by a silver chain. I should carry my wallet in my revolver pocket, as Americans do. I should have to make an elegant gesture in order to look at the time on my wrist-watch. I should put my hands in my jacket pockets, with the thumbs outside, and not, like the nouveaux riches, in the arm-holes of my waistcoat.

I should have a mistress, an actress.

We should go, she and I, to have an apéritif on the terrace of the largest café in Paris. The waiter would roll away the pedestal tables like barrels to make way for us. Ice-cubes would float in our glasses. The cane of the chairs would not be coming to bits.

We should have dinner in a restaurant where there were table-clothes and flowers elegantly arranged.

She would go in first. Polished mirrors would reflect my form a hundred times, like a row of lamp-posts. When the manager bowed his greeting to us, his starched shirt-front would bulge from the waist to the collar. The solo violinist would sway backwards and forwards as if on a spring-board, balancing his body. Locks of hair would flop over his eyes, as if he had just come out of a bath.

At the theatre we should have a box. I should be able to touch the curtain if I leaned forward. All round the auditorium people would look at us through opera glasses.

All of a sudden the footlights behind their zinc screen would light up the stage.

We should have a sideways view of the stage-set and, in the wings, actors not moving a muscle.

A fashionable singer, with jet buttons, would throw us a glance after each couplet.

Then a dancer would spin round on her pointes. The yellow, red and green spotlights which followed her would fall unevenly like the colouring of a picture by Épinal.

In the morning we should go by taxi to the Bois de Boulogne.

The driver’s elbows would move.

Through the shuddering glass of the windows we should see people standing still and others who seemed to be walking slowly.

Skidding round a bend, the taxi would throw us from our places and then we should kiss.

When we arrived, I should get out first, lowering my head, then I should give my companion my hand.

I should pay without looking at the meter. I should leave the door open.

Passers-by would watch us. I should pretend not to see them.

I should receive my mistress in my bachelor’s flat on the ground floor of a new house. The building’s plate-glass door would be protected by flat, wrought-iron palm-branches. The bell-push would glitter in the middle of its bronze surround. The mahogany of a lift at the end of the corridor would be visible from the doorway.

I should have had a shower in the morning. My linen would smell freshly ironed. Two of my waistcoat buttons would be undone, making me look relaxed.

My mistress would arrive at three o’clock.

I should take off her hat. We should sit on a sofa. I should kiss her hands, her elbows and her shoulders.

Then we should make love.

My mistress would throw herself back, drunk with passion. Her eyes would become glazed. I should unfasten her dress. To please me, she would be wearing a chemise with lace on it.

Then, murmuring endearments, she would give herself up to me, moistening my chin with her kisses.

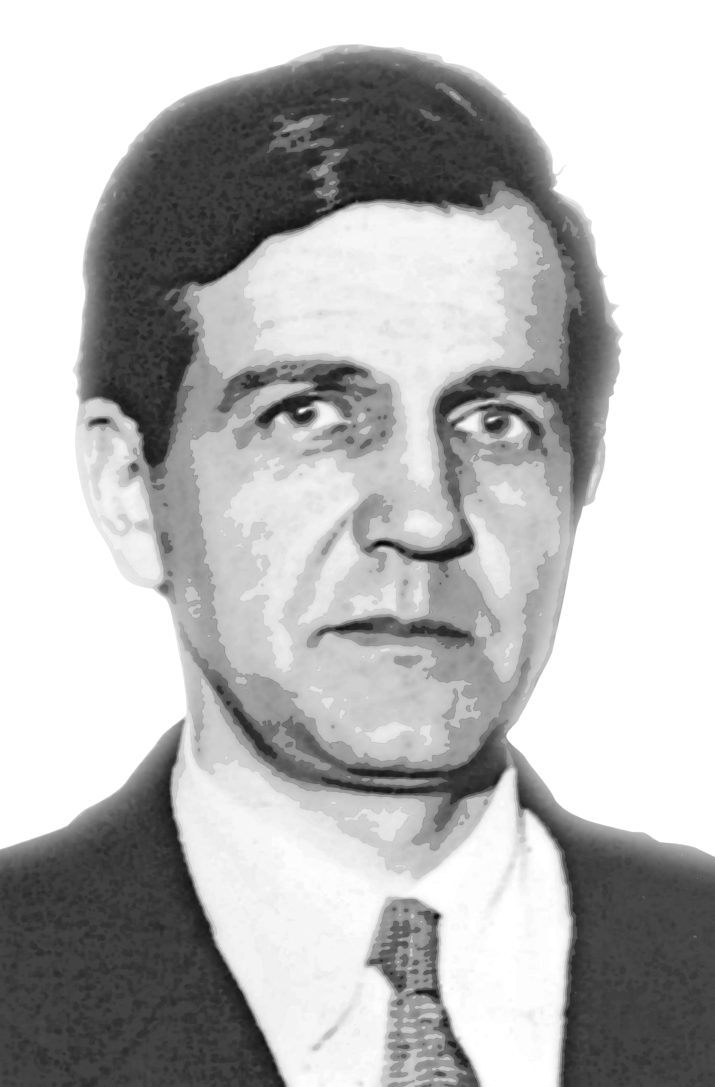

Emmanuel Bove (1898–1945) was born Emmanuel Bobovnikoff to a Jewish émigré from Kiev and a Parisian chambermaid from Luxembourg. His childhood was spent in Paris, marked at times by extreme poverty in the company of his mother and younger brother, and wealth in the company of his father and stepmother. With his stepmother’s patronage, Bove acquired an education in Paris, Geneva, and, during the First World War, England. Back in Paris, he began writing while supporting himself with a series of odd jobs. He had been publishing popular novels under the pseudonym Jean Vallois for several years when Colette helped him publish the novel Mes amis (My Friends) under his own name. He continued publishing successful novels, including Henri Duchemin and His Shadows (1928), also available as an NYRB Classic, until the Second World War, at which time he was forced into exile in Algeria. He died of heart failure soon after his return to Paris.

Janet Louth has translated several books by Emmanuel Bove, including My Friends, Armand, and A Man Who Knows. She lives in Manchester, England.

This excerpt from My Friends was published by permission of New York Review of Books.

Published on April 5, 2019.