Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire.

Bassel deposits his briefcase in the hall, removes his jacket and puts it neatly over a coat hanger on the coat stand. Once tall and slim, Bassel’s body is no longer immune to time’s passing – his hair has gone grey but at least it hasn’t fallen out like most of his contemporaries’, his belly has grown soft and visibly convex, and his back is no longer strong and straight. A slipped disc a year ago came as a rude reminder of advancing age.

He notes with satisfaction that the table is laid and the mezze already served. He shuffles into his slippers and goes to the kitchen, where his children are standing side by side at the stove.

‘Good evening.’ Bassel kisses each of them on the cheeks. ‘What are you cooking?’ he asks, lifting the saucepan lid as he speaks. Food has always brought him joy. Now he burns his lips on the hot spoon.

Amal wags an admonishing finger at him and laughs.

‘Fatteh,’ Ali answers, and Bassel nods. Then he pours himself a glass of wine and sits down at the kitchen table. There’s a beguiling scent of saffron in the air.

‘How are things at the Institute?’ he asks Amal.

‘Fine,’ she says, bored. ‘We’re rehearsing Wannous.’

‘All that stuff about the Palestinians again?’ Bassel sighs.

‘What else?’ Ali comments.

‘It’s perfect right now – they say there are Israeli agents on the streets stirring up the public,’ says Amal, barely able to rein in her excitement. Her cheeks are aglow. She expects her father to agree.

‘And I very much hope you two are staying away from the demonstrations.’

Ali and Amal stare at their father.

‘You think it’s romantic but there’s too much at stake, we’re not ready for a revolution. We don’t have political parties or civil society. Our civil servants are corrupt and ineffective.’

‘It can’t be stopped now,’ says Amal.

Ali listens without comment, crunching on a piece of carrot and waiting for the storm to pass.

Bassel waves his arm to dismiss Amal’s words and lowers his voice. ‘Oh, yes it can! They mowed everything down in Hama in 1982 and after that no one dared to raise their voice. It’ll be just the same this time.’ His voice has a touch of irritation to it.

Hama has become a code word, conjuring up memories of the last uprising and intended to curb this one. The Hama rebellion was launched by the Muslim Brotherhood. To consol-idate his position in power, Hafez al-Assad sent in the military and had the entire city demolished. People were put up against the wall and shot, raped, thrown out of windows, run over by tanks and slaughtered in the hospitals. This punishment went on for three weeks, with entire neighbourhoods reduced to rubble. No one spoke about the events in Hama, no one reported on them, no one documented them. Even today, no one knows exactly how many people were murdered there. But they know what price the regime was prepared to exact to stay in power.

‘Society could reorganize itself, on a democratic basis,’ Amal says, trying to stand up for her ideas again. ‘We could learn.’

‘You’re too old to be that naïve,’ Bassel replies as he lights a cigar. ‘And anyway, that’s not how I raised you.’

Bassel glares at his daughter with patriarchal fervour. Amal withstands his gaze.

***

After her rehearsal, Amal finds one hundred and sixty-three calls to her phone from ‘caller ID blocked’. When she picks up the one hundred and sixty-fourth call, a rough voice says: ‘You whore, do we have to call you a thousand times before you answer?’

Amal hangs up before the man can say anything else. The phone rings again immediately and she slings it against the wall, shattering the casing. She fishes out the remains of the SIM card and flushes it down the toilet. She sends Youssef a warn-ing from her computer and then deletes her Facebook account.

So the secret service has found her. Amal knows she has to act quickly. A few of her friends have already been summoned to interrogations that went on for days. She knows she has to either leave the country or find someone who’ll put in a good word for her with the regime. That someone will be expensive, though, and hard to track down.

She goes to her father’s office; he’s now running a construc-tion company. He values his position and his office, which is in an expensive part of Damascus. Most of all though, he loves hunting down new prestigious building commissions, which is why his children rarely see him these days – or that’s how he explains his constant absences. Here in the air-condi-tioned, sunlit rooms, which have a sense of luxury rather than elegance, the latest addition to the décor is a portrait of Bashar al-Assad. A huge photograph in a heavy, mahogany frame. Amal looks at the picture for a long time. She jumps when her father puts his hand on her back. He smells of cigars and disinfectant.

‘I though photos in the office were a distraction?’ say Amal, adding, ‘At least that’s what you always used to say about putting up photos of us.’

‘This is different,’ Bassel explains coldly as he puts his arm around Amal’s shoulder. ‘Did you just happen to be passing?’

‘I’ve got a problem.’

He raises his eyebrows and then asks quietly and in Russian, ‘Is it something we should discuss outside?’

Amal hasn’t heard Bassel speaking Russian since Svetlana’s disappearance. She’s unsettled by it now and tries to read his expression. Bassel guides her out of the room.

The two of them go down to the garage and get into his car. He turns on the radio and then gestures to Amal to speak. She takes a deep breath and tells him about the phone calls.

‘You’re going to get a summons,’ says Bassel.

‘I know,’ says Amal.

***

A few days later, Bassel has chased down a high-ranking govern-ment official with whom he studied in Moscow. In return for a generous sum, he is to get hold of a secret-service officer to make sure nothing happens to Amal in the event of her being summoned.

A week later, Amal receives a message on her new prepaid phone from ‘caller ID blocked’, instructing her to report to the Air Force Security Service headquarters the next morning. That same day, Bassel hands the official an envelope stuffed full of dollar bills, in exchange for the promise that Amal won’t be arrested.

A few days later, Bassel has chased down a high-ranking govern-ment official with whom he studied in Moscow. In return for a generous sum, he is to get hold of a secret-service officer to make sure nothing happens to Amal in the event of her being summoned.

A week later, Amal receives a message on her new prepaid phone from ‘caller ID blocked’, instructing her to report to the Air Force Security Service headquarters the next morning. That same day, Bassel hands the official an envelope stuffed full of dollar bills, in exchange for the promise that Amal won’t be arrested.

The Damascus headquarters are known as the ‘Holocaust’. There are several secret services, in fact, and each of them has at least one branch office in every part of every town, down to the tiniest village in the country.

A roadblock has been set up outside the entrance. Several police cars and a tank flying a small Syrian flag guard the building. The tiny forecourt is made of concrete, the high walls wrapped in barbed wire. Masked guards cradle primed machine guns on every corner, and the various men in grey suits with guns slung loose around their hips are impossible to overlook.

A young soldier leads Amal and her advocate along endless corridors with tattered carpet and yellowed wallpaper. The walls are dotted with identical portraits of Bashar al-Assad. The soldier rushes ahead so fast that Amal has trouble keeping up with him without breaking into a jog.

In the end he stops outside a solid iron door. It creaks loudly when he opens it with some effort. Inside the general’s office, where power reaches its zenith, a deathly silence reigns. An unpleasant smell has lodged itself in the upholstery. There are no photographs of the president here, not even behind the general’s desk. He now clears his throat for the first time. At that very moment, Amal feels an irrepressible need to go to the toilet. The advocate has left the room again in response to a gesture Amal wasn’t able to interpret.

‘Were you at the demonstration outside the Libyan embassy?’ the general asks through his huge moustache, with no pretence of an introduction. He stands there with his legs apart and his belly extended, puffing greedily on a cigar. The smoke quickly fills the small room.

Amal is suddenly reminded of how her mother used to say the size of a man’s moustache was a measure of how often he hit his wife.

‘Yes, I was,’ Amal answers.

‘Why?’ His eyes wander to her long fingers, bearing neither wedding nor engagement ring. ‘Has Gaddafi done anything to you?’

‘I thought it was authorized.’

‘Who gave you permission to think?’ The general looks her firmly in the eye and Amal tries not to evade his stare. ‘How did you get the idea the demonstration might be authorized?’

‘Because so many people posted it on Facebook. I thought it couldn’t be illegal.’

‘Well, we all make mistakes. I won’t hold it against you. What happened then?’

‘The demo was broken up,’ says Amal, pressing her thighs together.

‘And then?’

‘I went home.’

‘But before that you went to another demonstration, didn’t you?’ The general doesn’t wait for her response, instead open-ing up an outmoded laptop on his desk and playing a video for Amal, showing her holding a banner and singing a revolution-ary song, clearly recognizable. The general has a slight air of a boa constrictor about him.

‘Did you take a wrong turn on your way home?’ he bellows. ‘I was on my way back from the other demo and I happened to see this one. It was on my way home.’ Amal shrugs and tries to keep her voice free of any emotion.

‘Aha.’ The general raises his left eyebrow without further comment and then plays another two videos of Amal demonstrating.

Amal says nothing and neither does the general. His face is only inches away from hers. His eyes are bloodshot and his chin trembles. Amal has the feeling saliva will start running down the trembling spot any minute now. She smells his cigar and his aftershave, which must consist of a combination of heavy woody notes and cheap alcohol, and beneath that she smells vodka. After a while he says, ‘Young lady, there’s one thing you have to understand. We’re not going anywhere, even if Bashar goes away. We’re staying. For ever. And if we have to, we won’t just burn your kind, we’ll burn down the whole country. And now go, and tell your little friends their child’s play won’t get them anywhere. Tell them we’re staying. For ever.’

He calms down again and makes a note in large, childish handwriting on shiny paper headed with the words ‘Arabic Republic of Syria, Air Force Security Service Department’. Then he dismisses Amal. She now has a file.

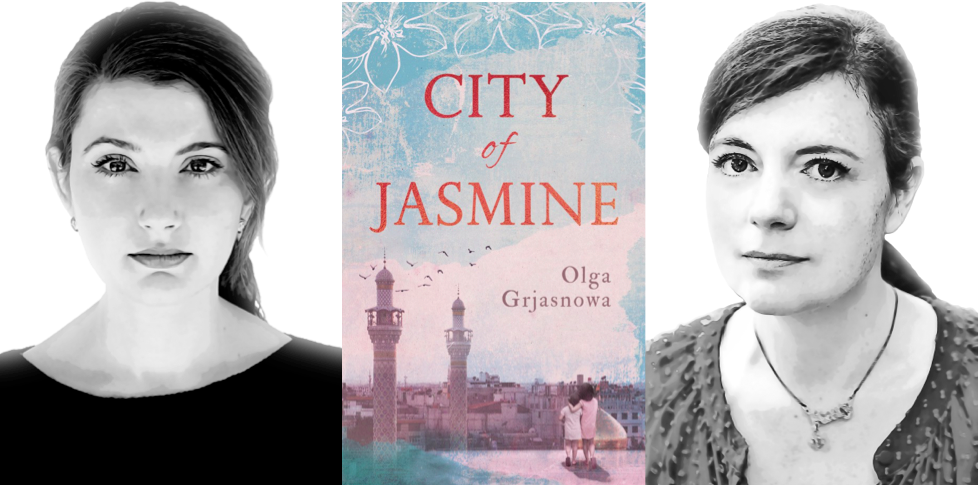

Olga Grjasnowa was born in Baku, Azerbaijan. Her debut novel, All Russians Love Birch Trees, was awarded the Klaus-Michael Kühne Prize and the Anna Seghers Prize. City of Jasmine is her third novel. She lives with her family in Berlin.

Katy Derbyshire, originally from London, has lived in Berlin for over twenty years. Her translation of Clemens Meyer’s Bricks and Mortar was longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize 2017. She occasionally teaches translation and also co-hosts a monthly translation lab and the bi-monthly Dead Ladies Show. Katy was recently awarded the Translator Prize of the Foundation for Art and Culture NRW – endowed with €25,000 – for her translation and advocacy work. Follow her on Twitter at @katyderbyshire.

This excerpt from City of Jasmine by Olga Grjasnowa, translated by Katy Derbyshire is published with permission from Oneworld Publications. Copyright © 2017 Aufbau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin, and Olga Grjasnowa. English translation copyright © 2019 Katy Derbyshire.

Published on April 5, 2019.