Translated from the Norwegian by David M. Smith.

This is part of our special feature, New Nordic Voices.

From: Lars Bakken <lars.bakken@nova.no>

Sent: July 20, 2001

To: Jamal <c.r.e.a.m@hotmail.com>

Subject: Survey of youths’ everyday lives in Groruddalen

Hi again, Jamal!

I’m writing because I haven’t heard back from you. This is in regard to the research project we discussed at Stovner Center, where we intend to use your story in our survey of the everyday lives of youths from minority backgrounds in Groruddalen. As a reminder, every participant will be entered into the drawing for a Scott mountain bike (worth 10,000 kroner) and a travel gift card of the same value.

Remember, you are not required to submit your answers in writing. You may also record them into a dictaphone.

It would be great if you could send me your reply. I hope to hear from you as soon as possible!

Yours,

Lars Bakken

Senior Researcher, NOVA

* * * * *

From: Jamal <c.r.e.a.m@hotmail.com>

Sent: July 22, 2001

To: Lars Bakken <lars.bakken@nova.no>

Subject: Survey of youths’ everyday lives in Groruddalen

i’ll talk in one of those things

send to tante ulrikkesvei 42a

* * * * *

From: Mo <mo.1@hotmail.com>

Sent: August 4, 2001

To: Lars Bakken <lars.bakken@nova.no>

Subject: Survey of youths’ everyday lives in Groruddalen

It was nice meeting you. I’ll do it, no problem. I like to write, I prefer that over talking, really. And I have lots of free time in the evenings after homework.

I should be able to write pretty regularly. Only I’m not sure if any of it will be of interest. To be honest, I can’t tell what it is you want to know. You said just talk about school, family, work and so on. I guess I like things to be a bit more specific than that.

But ok, I’ll just write some things about myself. Not a problem, really. I don’t know much about other people’s lives anyway.

I told my parents about this, by the way. They were fine with it. That’ll be good for you, they said, as long as you have time.

I live with my parents, as you probably gathered, and two siblings, my six-year-old sister, Asma, and five-year-old brother, Ayan. They’re practically twins. When people say that, Asma sticks her hands up in her face and screams, “Stop it!” Ayan just smiles.

Asma, Ayan, and Mohammed. I’m not sure what they were thinking, my parents. It’s tradition to name your first-born Mohammed, and the Prophet is the example that all Muslims follow; it was my mother, especially, who pushed for the name, but then they’re so fired up about me setting forth and getting a good job and all, so why name me that, exactly? It helps a little that people call me Mo, but still. People know.

My father came to Norway at the end of the 70’s. My mother followed a few years after. I was born in Oslo, at Aker Hospital. Lived in Stovner my whole life. I’m totally unfamiliar with the land my parents came from. No knowledge of it whatsoever. Stovner: that’s what I know. Boys wearing hoodies in front of the big housing complexes. Women in hijabs pushing strollers. Elderly Norwegians smoking and playing bingo. That Stovner. Housing-Stovner. Not House-Stovner. Everyone knows there’s a big difference. House-Stovner is filching apples out of the neighbor’s garden when his back is turned. Housing-Stovner is why we’re a dark-red blotch on Aftenposten’s map of the boroughs of Oslo: like a drop of blood soaked into the newspaper. Lots of immigrants. Lots of juvenile crime. Lots of dropouts. Lots of cashiers, nurses, janitors, people on welfare. Three siblings and two parents in a three-room on the eighth floor on Tante Ulrikkes vei, wallpaper and furniture from the 80’s, and an elevator that gets stuck just a little too often. The man below us is unstable, an addict, and he has a pit bull that has to sniff me every time I walk past. I hate dogs. Then we have old man Svendsen on the third floor. He comes out to rant and rave because the hallway smells of food and the stairs aren’t mopped. When the kids are making noise, he barks up the stairwell: “Quiet down, dammit!” To anyone who’ll listen, he announces that he’s “voting for Carl.” The kids throw rocks at his window and prank call him at the front door; he just yells all the more often and all the louder. Sometimes you hear him mutter: “God, the shithole this place has come to.”

Outside this apartment block, there are still more of them, high-rises and low-rises, the color of salmon. In the middle of the housing cooperative there’s a large sculpture of a flame. I never understood that: a monument to something burning. The planks of the bridge up by Stovner Center are green with mold, there are holes along the sides, and it swings. I mean it. You feel it sway up and down when somebody runs across it. It’ll collapse someday, I bet you anything. At Stovner Center, you see the same faces doing the same thing, day in, day out. Folks on welfare with too much time on their hands talking to other folks on welfare with just as much time, when they’re not playing the slot machines. And the youths, they hang around in clusters everywhere, Burger King or the Mix kiosk, yelling as you walk past: “I’ll destroy you, man, I swear.” If there’s anything I can’t stand, it’s the way they always have to yell at you that loud.

The bus stop and metro station are close by. Three people were machine gunned there in January. One of them paralyzed from the waist down. My parents don’t like me being there after dark. For that matter, neither do I. The Dane working the Narvesen kiosk by the entrance always treats you like his enemy, flinging your change so the coins bounce across the counter. Sometimes they fall to the floor and you have to pick them up. As if you’re bowing to him. The plexiglass doors to the station are covered with graffiti. Not just the usual markers and spray paint, but carved into the glass itself with a knife. The walls on the platform used to have graffiti from end to end. In the early 90’s they painted it over with a vibrant community, large profiles of children from all over the world. The colors have faded, the paint is chipped. It reeks of smoke and piss, especially on Sunday mornings, but regardless of the stench, George is always there, reaching up to his elbow in the trash for empty bottles. It’s disgusting even to look at.

That’s how I think. Sometimes. A lot, actually. I’m negative. I know it. It’s just…It’s a real struggle not to be…

But there were also times when I liked Stovner. When I was a child, especially. Then it wasn’t a spot of blood on a map. The complexes were homes. The graffiti at the metro station, murals. The welfare recipients, neighbors. All those brown little children, my friends. The white kids, too. I can still point them out in my yearbooks. Christian. Stian. André, Thomas A. and Thomas N. Children of the rainbow, the rainbow race: that was us at school. Culture days with food from all parts of the world. Field trips to mosques, churches, temples. At Rommensletta we played soccer, after which we tasted the best water in the world from the faucets at the clubhouse of Rommen FC, and ate raspberries on the hillside near the Fossum youth house. When we had any money, we bought twenty sticks of Bugg chewing gum at Vivo for ten kroner. I remember that. Birthdays with a long table decked out with garlands, Ninja Turtle cups, and chocolate cake with coconut shavings. Snowballs, frozen fingertips every winter, king of the hill on the snowbanks, and Nintendo at André’s house, until he was called to the kitchen for supper and we all headed home to receive ours.

That’s how it was, I think. Different. A different Stovner. A different Norway. And I was a child. Things changed when I got older, there’s no question. But you know, I wish it could have stayed that way a little longer. Longer than second grade at Rommen School. I know it’s silly, but sometimes I think: what if I hadn’t raised my hand to go to the bathroom that day?

That hallway, usually teeming with rambunctious kids, was totally still. With every step my sneakers screeched against the linoleum floor. I entered the bathroom. Now, that bathroom was a scary place. The air hissed through a duct. The urinal flushed by itself. It roared. I didn’t have much time. The devil lived in there, according to whispered legend, and came out if you stayed too long.

“He wakes up when it flushes,” they said, “and if you’re not outta there before then, you’re dead meat.” I splashed a few drops of water on my fingers. The door felt like it weighed a hundred kilos when I pushed it open and dashed out.

Back in the hallway, the screeching of my shoes blended with the sound of voices. Deep, grown-up voices, and angry. I slackened my pace, the screeching softened, and I stopped right by the corner where the voices were coming from. I heard clearly: the subject of all that anger was us.

So many foreigners at the school now. Mentally retarded, slow kids. Parents without a clue. Neighborhoods become slums. The dreaded walk to the metro after the sun had gone down and the gangs came out. The day they could finally take their pensions and get the hell out? It couldn’t come soon enough.

I think. A lot of it went over my head. But there was no mistaking one thing, and that was the extent of their distaste for us, the anger. In that hallway where I stood, they grew. Into giants. Horrible giants, like in The BFG, which we took turns reading out loud in class, giants that terrified me, not as much as when we read The Witches (that one caused me at least ten nightmares), but scared anyway, scared of those big giants who stole kids out of their beds and crushed them to bits between their huge jaws.

I got back to my desk and could only hear the smacking of lips, limbs being snapped, screams being screamed, my own scream perhaps, I don’t know, a scream coursed through the building in any case, but just then, the schoolbell rang, which was probably it.

On my way home, my stomach started giving me trouble. It rumbled, threateningly. I took off through the grass that was thick with dandelions, turning the tips of my shoes yellow. I couldn’t wait on the traffic lights at the intersection with Fossumveien. Instead, I took the tunnel that, in all truth, was no less terrifying than the bathroom at school, since flashers were known to lurk there, but I flew through it anyway, continued up by the telephone booth and the old Fossum School building onto the short path where there was always dog shit, which I leaped over and flew into the stairwell. As I waited for the elevator to come down from the tenth floor, I was sweating, hopping from foot to foot. When it finally arrived, I realized I couldn’t hold it any longer even if I clenched every muscle in my body to shaking.

I was so humiliated when I got in that I went straight to the bathroom and started to cry. I cried as washed my pants and underwear by hand in the sink, scrubbed them with my knuckles and Head & Shoulders, the brown stuff gushing out and flowing down the drain. Then I scrubbed myself until I was red from the waist down. I stood listening until I could hear that everyone had moved to the living room, then I ran to my bedroom in my underwear and hung up my clothes to dry in the closet.

I never told anyone about that incident. Not even my parents. I kept it all to myself, as if I’d been witness to a crime that would go away if only I kept my mouth shut.

I kept my mouth shut and realized that Stovner was a very small place, and Tante Ulrikkes vei even smaller. I realized that in Stovner, people lived in houses on one side and housing on the other, and that the two were nothing alike, something that held true for Oslo just as much as the rest of the world. I realized that those teachers weren’t alone. The morning paper and the six o’clock news were full of stories about us. About youth gangs where new recruits were forced to jump random people on the street. About how bad the schools were. About eighteen-years-olds who couldn’t read, much less write proper Norwegian. About the housing complexes that were soulless living machines, and that too many of the machines’ residents got all their money from the welfare office. I remember when they started to talk about integration on Dagsrevyen:

“Several politicians are sounding the alarm over the inadequate integration of immigrants.”

I didn’t know what they were talking about. It made me think about space ships, like the LEGO space ships when I was a kid, the ones with yellow glass and black wings. I pictured space ships taking off and integrating towards the stars. But that wasn’t it. This was down here on earth. Mosque every Friday instead of church once a year, turning down hot dogs at Christian’s birthday party, bickering over the proportion of beer versus soda on apartment volunteer day, showering in your underwear in the locker room, cousins marrying cousins, and women always three steps behind their husbands at Stovner Center.

Stovner received a fair share of visitors. Politicians outside the metro station expressing concern about the unsustainable and unacceptable situation. Or the lady from the family support center who dropped by school one day. I remember our teacher announcing a special guest, a little lady with huge glasses who came in and sat at the desk. She said there was something she had to tell us, it was a little difficult, but important to talk about.

“It’s not always easy for parents when your family is struggling to get by,” she said. Her face was serious, but the voice was a soft whisper, almost like Mrs. Doubtfire’s. “Parents can sometimes be in a bit of a bad mood if they are worried about finances.”

All through the next day, the kids went through school calling one another hoboes.

This isn’t the way things ought to be. I mean, it can’t be, right? It does something to people, I know it does. Some people here, they become so hardened. As though pressed together so tight they turn into stone. Others are content to let everything take its course. Just straight ahead, no matter what they bump up against. They go into work or off to school, oblivious to it all. Like Andersen on the fourth floor or Mahmoud on the fifth. They go home to their families and read the Aftenposten that’s waiting on their front doorstep, or they watch Dagsrevyen or satellite, cursing inwardly over what they’ve just been shown, remembering none of it by the time they go to bed.

Sometimes I could wish I was like them. Or those who’ve become hardened to it all. I don’t know. I feel like I’m the type that just crumbles apart.

Everything I grew up with was transformed into something foreign, mature, and toxic, but there was nothing I could do about it. I didn’t know what to believe about anything. I was a child who thought too much. More than was good for me. Moreover, I was aware of it, since it didn’t seem as if anyone else thought as much as I did. They certainly didn’t let on, if they did. I thought myself into anger, anxiety and weariness; everything blended together into a sense of unease in the pit of my stomach, creeping sometimes up, sometimes down. I suffered from nausea and diarrhea. My mother gave me fennel tea. It didn’t help. She put me on a diet of rice and white bread. That didn’t help either. When I was in seventh grade, she took me down to the doctor’s office by Stovner Hall. A bald man in clogs listened to me with a stethoscope and pressed an ice-cold finger to different parts of my stomach.

“Probably just puberty,” he said. “No medicine for it, really.”

There was nothing that could be done about anything, really.

Some tried. Michael, the head of the Fossum youth house who went on TV for years in defense of the Stovner Youth. The Norwegian mother down in number 19, pressing her case in letters to the editor that things weren’t as blood-red as the papers made it out to be, that Stovner was a functioning unit that consisted of perfectly normal neighborhoods. Or Amir, the law student who was so good with words, he went head-to-head with Carl Hagen in debates. And maybe you’re thinking it wasn’t only them, but many others, and I’d say you’re probably right, only I wouldn’t know, since I wasn’t hearing those other voices as much . Not as much as the voices on Dagsrevyen or in VG, the government ministers and city councilmen, all the high-pitched and deep voices that yelled in my ears constantly and forced my eyes wide open until I lay there all night watching the shadows dance along the wall. Only to get up the next morning and see the families of Thomas A. and other kids hoisting cardboard boxes and furniture into vans on their way to Nittedal and Ski and Skedsmo.

No one wants to be around the problem child.

Not even the Salvation Army, who used to strum their guitars outside Stovner Center every Saturday, singing songs about Jesus. They’re gone now, too.

But that’s enough for now. It’s getting late and I have business admin tomorrow at 8:15. I’ll write more tomorrow night.

*****

Respondent: Jamal

Borough: Stovner

Date recorded: August 5, 2001

Hello, you hear me?

Uhh…So, you said I’m supposed to tell you about my life, right? Like a diary or something? No way I’m doing that. I don’t like writing. Not in some diary, anyway. Shit’s for girls, man.

So I’ll talk instead, alright?

Ahh, shit. I don’t know. What am I supposed to say? I guess I’ll just start talking. No plan.

Ok, ok, I’m Jamal. Brown, Muslim, from Stovner, T.U.V., Tante Ulrikkes vei, yeah you know, represent always. Live here with my mother and little brother, Suleiman, but we just call him Suli. My father…pssh. Forget him, he’s gone, the tishar. Yeah yeah, I know, people tell me not to talk like that, ‘cause he’s my father and all. I could give a fuck.

My father is a tishar.

But anyway, what’d I say? Yeah, the high-rise, the first one, that’s where I live.

Ha ha! Fuck, this shit is crazy. Like, how am I supposed to talk to you?

I told my homeboys I’m doing this research thing here. They’re like, “Shit, bro, what the hell for?” I’m like, “He’s gonna give me stuff, worth ten bills, man.” So I better win one of those things you told me about!

You know, it almost feels like I’m rapping here. Like, I know this thing ain’t a mic, only a dicta-whatever, but I swear, that’s sort of why I’m doing this, so I can just like, talk about my life on the microphone and people can hear what I’m saying, you know?

Everybody wants to be a rapper. They may not act like it, but they do. Kinda like me, not that I think I’m the bomb, chill out, I know I’m not. I memorize all these rhymes from different rappers, but whenever I try to do it myself, nah man, it’s hard. My rhymes are so tæz.

But yeah, I’m into so many rappers. 2Pac, Nas, Jay-Z, Biggie, Snoop. Gangster rap and street and all that, but you know, I like some of the others too, anyone who can kick it, really. Outkast and stuff.

I love hip-hop. Always have. Ever since I was, I mean, when we were kids we would listen to MC Hammer and all, but when I was maybe twelve, no, eleven, I was hanging out with my friend Rashid, and his big brother, Mustafa, he’s like four years older than we are, and pretty much always a tishar to us and ragging us out for some shit. Go outside and talk, you’re bothering me, or else it was, you don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about. And I can’t say anything since he’s my friend’s big brother, and he could kick my ass, easily. I’ve seen him do it plenty of times to Rashid if Rashid talks back or anything. But anyway, he’s got his stereo and he brings out this one album and he’s like, “Boys, I’m telling you, this shit is the baddest music on the planet right now.” And we’re looking at this thing, there’s these kung-fu people on the cover and the name of it is Enter the Wu-Tang. We were just like, what the hell is this, chop-suey music or some shit? But then he puts it on…

It was sooo intense, you have no idea, man. I swear I’m getting goose bumps here just thinking about it. I’m telling you, it was the ghetto blasting from the stereo. It was so real, you know what I’m saying? And those beats, those beats are just chaos, man. Just listen to “C.R.E.A.M.” or “Tearz.” Just do that, and then come back and tell me that’s not the most baddest shit you ever heard.

From then on we were just Wu-Tang crazy. All the boys. Rashid, Majid, Tosif, Navid, André, Abel. Like, everyone had to be one of them. André, he’s Ghostface, but not Killah, right, since you know, he’s white, and Rashid is Raekwon, I’m Method Man, Navid is GZA, Abel is Ol’ Dirty Bastard and we’re at Rommen School like, “T.U.V. Clan ain’t nothin’ to fuck with.”

Ha ha. Funny shit.

But with hip-hop, I swear man, it’s like no other music really speaks to me. What else is there? Bon Jovi? Aqua? Britney Spears?

Fuck all that.

I’m no nigga from Compton, but like, I sort of am, you know what I mean? You know what all’s here at Stovner. Pakkis, niggas, degos, chinamen, yoghurts, Arabs, lankers, you name it.

It’s like, we’re all brown in a country of white people, you know?

But that’s exactly what hip-hop is all about. Hop-hop is all about hanging on the streets, smoking weed, hooking up with bitches and all, that’s how we live, right. And they’re always like, be proud of your hood, even if others talk shit. And you know all the people who talk shit, man. Constantly. “Stovner is the most tæz place in town.” “Immigrants are tæz people.” And shit like that.

But I mean, those ‘taters that live here in Stovner, they’re alright. The young people and all. Like André, he’s our homie. But the old ones, man. So many of them are straight-up racists, I swear. Voting for Carl Hagen and shit. Or it’s like, when me and my friend were just little brats sitting at the window, “Hey yo, this ain’t Africa. Get down from there, ya bloody apes.” I will never forget that shit. Or them ‘taters in houses in Stovner, so many of them strut around like they’re the fuckin’ cream of the crop, like they’re from the west side of the city, and then you find out they live right over here, in fucking Høybråten! But I swear the worst ones are the ‘taters from other parts of Oslo and around Norway. The ones that go on TV and talk shit about us, and they’ve never even been to Stovner or so much as shaken a brown person’s hand.

Like, what’d I do to them? So fucked up.

But nowadays, now we’re all just like, fuck all those haters, right? Represent no matter what. Represent T.U.V. and Stovner, forever. Forget all them others in this country. We don’t need them. We got all this here, you know what I mean? We got these high-rises. These people, right here. That’s who we are. Don’t let the haters get into your head, telling you you’re tæz and all. No way. You’re schpaa, man.

For real, sometimes I’ll put on Nas’s “Represent,” the one where the beat starts out sort of slow but then it takes off and gets totally banging, Nas is spitting out the lyrics and flowing so sick and I go around and look at these high-rises and this street and the music is blasting and I’m just like, goddamn, this shit is so tight, I swear, I almost want to cry, but at the same time I’m happy.

Like, we know the hip-hop, the hip-hop knows us, right?

Shit, I’m almost rhyming here!

Ah, man, you don’t even know how ghetto I am right now. I’m talking to you in the bathroom. Ha ha. What am I supposed to do? My brother’s asleep in his room.

Here, listen, I’ll flush.

But yeah, hear this. I don’t have a computer, so I can’t check my email a lot. When I’m on a computer it’s mostly Napster and shit. Or other stuff, you know, porn and all.

Chill out, man, everyone does that, I bet even you. That’s probably all anybody does at that office of yours, the second no one’s looking. Just like at school: oh shit, here comes teacher, click the x, click the x! And that just brings up twenty new porn windows and we gotta unplug it, and we’re like, uhh, I dunno teacher, it just turned off, man.

Ha ha.

But anyway, I gotta go. Talk to you later, NOVA-man. Sorry, forgot your name.

Peace

*****

From: Mo <mo.1@hotmail.com>

Sent: August 5, 2001, 9:05 PM

To: Lars Bakken <lars.bakken@nova.no>

Subject: Survey of youths’ everyday lives in Groruddalen

Just so you don’t think so, it’s not like I all I do is complain. I don’t hate Stovner either. I don’t, really. It’s more like—I’m not sure how to explain it—like it reeks here. Not just in the metro station, but all over Stovner. Like an old rag that’s been hanging on the kitchen faucet and become stiff and stinky. And I’m not sure when it began, it was probably gradual, but I started to wish for something, anything really, to keep that stench away.

It was at middle school—as if things weren’t confusing enough already—things came to a head. I had to have something to latch onto. And having never found that at Stovner, I looked to the outside.

The more I thought about it, the more obvious it became. If life in Stovner was so hard for so many, most of all for me, things had to be better on the outside. It was that simple. And when I first found that thing to latch on to, with each new day, the thought of everything out there expanded. A footless escape, through hundreds of daydreams. On the way to school. At school. On the way home from school. Countless hours in my room, staring at the ceiling or out the window, while Asma and Ayan played with dolls and cars on the floor next to me.

I’d put myself in different places, places I imagined to be the opposite of Stovner. Places I’d seen on TV, or on trips through town, like the drive to Fornebu when the airport was still there, or when we visited a friend of my father’s at Høyenhall. I placed myself on the staircase of a big house, or in a trendy café together with trendy people, or on the deck of a boat in the sunshine on the Oslo Fjord. All very different places, to be sure, but all of them had something in common: they were all peaceful, no one was angry. I had no name. No one had any name. No one looked like this or that; and everything blended together, as if what I was in Stovner meant nothing anymore, in this imagined place.

It’s a little embarrassing, but that’s the sort of thing I would fantasize about. That was the basic fantasy, though I would add more to it as time went on. Girls, particularly. Not girls from Stovner, but the kinds of Norwegian girls you’d see down in the city in the summer. Ridiculously hot, of course. And then, money. Lots of it. A good job that I go to in a suit. A car that makes people’s heads turn. I’m standing in my big garden, exchanging small talk with a neighbor who smiles. I stuff everything into those fantasies. They take up every last bit of blank space. If my siblings are too noisy, I go outside. Walk in the forest at Stovner, the one down by Rommensletta around Tante Ulrikkes vei and Smedstua, or sometimes down by the flood-lit ski trail at Liastua, seeking the quiet that will let me really get into the fantasies proper, and I need that, that false start, before my impatience gets the better of me.

That’s really why I am so occupied with school right now. My parents too. They’ve said it a million times since I was little: go to university, get a degree, a good job, big house, nice car, pretty wife. Little do they know, they’re just fanning the flames that are already there.

Especially my father. The man who won’t fall over no matter how hard the ground shakes, just grabs hold of the nearest object and won’t let go. Like when I was in school, for instance. Often he was the only immigrant father to show up to parent-teacher conferences. He would also sit down with me every night to help me with homework until the assignments became too hard for him, and now his job is more inspector, checking in now and then to make sure I’m working, giving me a supportive nod.

I remember when I started eighth grade and they put me in Norwegian 2, as they probably did to everyone with a name like mine. They’d have bumped me up after the first test anyway, but I’ve seldom seen my father as mad as when I told him about it.

“What!? Why!?” he yelled. It wasn’t directed at me, and still I backed away, my eyes fixed to the floor. “Are they idiots or what?” He called the principal that same day. Next day I was in Norwegian 1.

Thanks to him, I got out of Koran school several years before other kids, so I had more room to remember everything from regular school. I was there less than a year, during which I read the Koran cover to cover and learned how to pray. That was it. Now I can recite the testimonial word and the supplication. Everything else, gone. Fasting on Ramadan, gone too. I got out of that, since who can concentrate on an empty stomach, as he put it. My mother insisted I observe it on the weekends, but even that ended in middle school, when I was often studying for tests on weekends as well. We go to mosque twice a year now. For Eid. My father and I stand on a soft rug in a repurposed factory building at Galgeberg and pray. We head for home when the service is over.

I think he’s the reason why I have so few religious feelings.

“He knows so little,” I heard my mother sigh to him once. He didn’t say anything.

Sometimes, more in the past really, when she and I were out by ourselves at Stovner Center buying groceries for instance, she would recite Surahs from the Koran, hadiths and du’as she wanted me to understand and repeat after her. Usually it ended with her yelling at me with irritation: “Mohammed, listen!” as I jumped from boulder to boulder along the street, trying to keep my balance with the bags of milk and bread.

I spend a lot of time on schoolwork, but I can’t remember ever really enjoying it. It comes easy, always has. I don’t know. I retain most of what I read. And I like straightening things up, that’s probably part of it. The school wants things orderly and neat. Just give me a big pile of stuff and I’ll clean it up. Sometimes to a fault, since I get really stressed when things are lying around, and often I’ll clean so much that I have hardly anything left once I’m done. My favorite subjects are those that involve putting things in order: math over social studies, science over Norwegian, economics over history.

Elementary and middle school bored me. I hated the schoolwork, the long days, the hours that stretched out endlessly. The dry air from the old radiators at Rommen that made me tired, the orange curtains that smelled like winter clothes when we unboxed them in the fall. Whenever I hear people say they like learning, I don’t get it. It’s not for me, I think. I read schoolbooks at a pace no one else on Tante Ulrikkes vei comes even close to, I do lessons that other students don’t bother to do, and I cram for tests as though my very life depended on it; it’s the only way I know to get out of the forest at Stovner.

But it’s not always just school, school, school. I’ve been to parties, school reunions. I’ve had one girlfriend. One. At the end of seventh grade. It lasted one month. Mostly, it was just weird. She came up to me at the school dance and asked if I’d like to take the floor with her. Linda. From Chile. She was alright. Not the prettiest, but not ugly. Not hip, not a nerd. She just hung around vaguely in the middle, like me. We danced to “When Susannah Cries.” She had on her Buffalo platforms, the highest there are, the soles had to have been 10 centimeters thick at least, she towered over me. I danced on tip-toe. My legs ached, I had to stretch my arms up to get them around her waist. I knew I probably looked like the biggest idiot. Some of the guys saw us and laughed, goaded me to grab her butt. “Do it man, do it,” they mouthed. I didn’t, but I was exhausted when it was over. On the way home her friend came up to me.

“Linda wants to know,” she said.

“I’m not sure,” I said.

“Well, you better say something,” she demanded.

“Yeah, ok, I guess so.”

So we started going out. I didn’t know the first thing about girls. I’m serious, absolutely nothing. I had no idea what going out with someone involved. Like how I was supposed to do a bunch of stuff, and the fact that Linda would be put out if I didn’t take the initiative and hold her hand. And then she wanted to talk on the phone every day, but got mad when I told her not to call my house because then my parents would know. After school we hung around the area a little, sat on benches, or went over to the Center to look around in stores, take photos inside the booth, or buy a soda to share. I can’t recall us talking all that much. In any case not what about. We sort of just hung out next to each other in the same place. The kissing was good. Lots of little pecks, one after the other, maybe ten in a row. I never really got the hang of how to use the tongue, but I liked it anyway. Beyond that, it mostly amounted to a lot of stress.

On Saint John’s Eve, she rang at the outside door. During Norway-Brazil. Luckily, I was the one who answered the intercom.

“It’s me,” she said.

“Who’s me?” I asked.

“Hey, come on—it’s Linda.”

“What a jerk. Always so superior,” said another voice. “Come down,” said Linda.

My father yelled. “Come over here! It’s a goal! Flo!” That was the one name he knew. He got it right, for once. Arne Scheie’s voice followed: “We have scored in Marseille!” I stuck my head inside the living room and saw Norway take the ball out of the net behind Taffarel.

“Be right back,” I yelled and sprinted down the stairs.

They stood by the entrance, looking serious. The friend spoke and said that Linda and I needed to talk.

“Can we make it quick?” I said. “It’s the game with Brazil, and…”

Linda was cross again. “I’m rooting for Brazil. Fellow Latinos.”

I think I said it was silly not to root for Norway when she lived here. It wasn’t even Chile. She said that soccer was silly, anyway.

“Yes! Penalty!” a voice rang out of an open window. I was itching to go back up. Linda had something to say, but kept it to herself. A minute passed. Then the whole neighborhood erupted. We heard it above us. In front of us. Behind us. People were beside themselves. “Yes, dammit, yes!”

“Out with it,” said the friend, giving Linda a light shove.

“I think you act superior,” said Linda. “It’s like, you just don’t care at all.”

“Well, I don’t know. I mean…don’t I?” I said.

The howls started again. Even more of them, and even louder. People streamed out of the stairwells. Two grown men with huge beer bellies embraced one another and hopped up and down. Another had a little Norwegian flag, waving it feverishly like a kid in a May 17th parade. Children came out with soccer balls, imitating Rekdal’s game-clinching shot. The air was brimming. The cars on the roads gave a chorus of honks. The smell of a bonfire wafted over from someplace else.

“Time for us to go,” said the friend.

“Ok,” I said as I stood watching the commotion.

They started to walk. Maybe twenty meters away, Linda turned and yelled across the yard:

“We’re finished, just so you know.”

“Ok,” I yelled back, with a look up to our windows on the eighth floor. They were closed, fortunately.

That was it, really. I haven’t had any girlfriends since. I don’t go out much or take part in many activities after school. I never hang out at Fossum Club or the Rock Factory. I drink a little if I’m out at a party, but then I’m hardly ever at parties. I do like to smoke, though, it helps me relax. But while others go full throttle into all that, I keep my distance. Especially now, in high school, now that the daydreams have grown in step with the pressure to get good grades, I just stay in most of the evening.

Sometimes I hear them on weekends. The beer bottles knocking against each other inside their plastic bags, or a quiet summer night, when it never gets totally dark and I lie in bed with the ventilation open as I hear them laugh till they cry and play street soccer and smoke.

I’m lost to them, the ones out there. I’m the weird kid, I know they think so. Like them, only not. Norwegian 1, not 2. Speaking the language of the schoolbooks, not the streets. The kid they see on the way to and from school, but never anywhere else. The kid they wave at and might talk to now and then, but never call. The kid they just leave alone, to himself. I am that kid, long accustomed to the outside, even though I wear the same Adidases and tramp around the same sidewalks.

I mean, really it doesn’t bother me all that much. I’m used to me, if you get what I mean. I’ve always felt like an only child anyway, even with Asma and Ayan. After all they’re ten, eleven years younger. I’m not very social around people. I’m able to talk to those who talk to me first, but I’ve just never been comfortable talking to people I don’t know, out of thin air. I don’t need all the parties, to be outside all the time. I don’t want to. Really. I’d rather just stay inside and daydream about other things, alone. Focus ahead, all the time, that’s what works. Don’t look from side to side.

*****

Respondent: Jamal

Borough: Stovner

Date recorded: August 15, 2001

Check one, two.

Just kidding. I know I go on about hip-hip all the time, but I won’t rap here. So just chill.

I’m not in the bathroom this time, by the way. In my room. Suli’s in the living room with my mother. She’s sitting on the couch. She’s like, always worn out. She gets her dough from welfare. She used to try and claim disability, but the welfare office, they were like nah, man. They didn’t want to make it a regular thing, so she’s getting, what’s it called, temporary whatever, and it’s a hell of a lot less. She’s gone down to that office, but every time they’re like, she’s not enough sick to get it regular. Ain’t sick in the body, they say.

Man, I dunno. Come by and see for yourself whether she’s not enough sick, you feel me?

She’s on that couch so much. I go out, she’s there. Come home, she’s there.

But whatever.

What was I going to…

Yeah. My life and all. School just started back. Bredtvet High, you know. They just shoved me in that school. I didn’t choose to go there or anything. Last year, things didn’t quite work out right. So they sort of said to me that I got to repeat a grade because I failed too much last year. I’m like, ok, fine, my mother’s telling me I got to finish high school and all.

I’m always sweating at school. I swear, my head like, overheats there. I’m sitting there, following along—sometimes, anyway—and I don’t get everything the teacher’s saying, I mean, a lot of times I understand a little, not in math, but anything else, I understand what they’re saying when they’re saying it, anyway I think I do, but when they give assignments or something to read or whatever, I dunno, my head feels hot and my body just feels worn out. I don’t know, it’s like, I can read, you know? But when the teacher asks me what it says on the page we just read, I already forgot it even if it was two minutes ago, or like with assignments, I just can’t think, and I just want to go to sleep, and I start to think about other stuff, stuff at home, you know, or stuff outside, anything.

School is like that every day, for real. I do other stuff during class, sleep or whatever, draw the Wu-Tang “W” on my desk, and the teacher starts giving me shit. Never trying to help, just giving me shit. It’s always, “Ya-mal, get to work.” “Ya-mal, wake up.” “Ya-mal, you need to pay better attention.”

Ya-mal, for fuck’s sake. It’s pronounced Djamal, got it? Dja and mal, it’s not that hard, but those fucking ‘tater teachers, they never even tried to learn it right, even after I said it probably twenty fucking times. And they say it’s time I start learning?

They put me in Norwegian 2. “You have problems with language. It’s ruining your studies.” They started going in on all that. I was like, what are you talking about? I speak Norwegian, I can understand almost all the Norwegian they say to me. So what if I just fuck the words around a little.

That’s not the problem.

Norwegian 2, man. Only brown people are in there and the lesson plan’s a joke. One time, I swear we spent three months talking about what we did on summer vacation.

So messed up.

But I didn’t say anything about it. I just thought, this is better than Norwegian 1. Norwegian 1 is hard. Norwegian 2, I can take it easy. It’s all chill.

So, I sleep or goof off more and more during class, and they keep getting madder and madder. At middle school I started to talk back a little more, like shut up, I’m not messing with anyone, don’t mess with me, dammit. They sent me to the principal’s and told me to take a moment.

That’s how it was.

They don’t understand a goddamn thing, I swear.

But anyway, it’s Bredtvet now. Rashid is there. The other guys are at other places. Like, Tosif at Elvebakken, Navid at Stovner, André at Stovner, Abel at Hellerud, Majid at Sogn—really, Majid’s a slacker, so I dunno. But there are tons more Stovner guys at Bredtvet, some in my class too. Some from Furuset and Ammerud. I don’t like them so much, the Ammerud guys. This one guy was eyeballing us hard that first day in the schoolyard. We just eyeballed him back and he sort of backed off. But they’re totally boss at lifting baguettes and Coke at Prix. Seriously, they come back into school with like three baguettes, two school buns and five Cokes. Fucking kleptos, man.

Then there are some Veitvet and Rødtvet guys. Some of them are brown and some are ‘taters. I don’t really talk to them, to be honest. But they’re ok, don’t cause a lot of chaos or anything.

This one guy smokes weed, I found out already. Arsalan. Pakistani. Hangs with the B-Gang kids at Furuset. He says that, anyway, but you know how guys talk: “I know him and I know him. Wallah, I can just call him up.”

But you know, in lunch hour I went and smoked with him down by the lady prison there.

So yeah, I smoke it.

So what? That stuff won’t kill you. I mean, it’s better than other stuff, right? Nobody causes any chaos or bad mood when they’re high. Never. Like, when do you see people kick the shit out of someone else when they’re high? Never. Weed is chill, man, that’s why I like it. You know what you’re doing, right, even though you’re on weed. When people drinking and all, or take pills and coke even, that’s when you see guys doing sick shit. You wake up and you don’t even know what you did yesterday. Or else you get like Nico, the juicer at the stairwell on the other side of me. This bouncer guy. Totally brutal. Huge as fuck and tattoos up and down his arms. Like, if he’d have gone into wrestling, he’d have gone against Hulk Hogan and shit.

He’s got his pit bull, too. Diesel. You see him coming, you get on the other side of the road. Bigger than a lion.

This one time Nico had been chewing roofies and came out with that mutt of his, and that dog wouldn’t listen to him. It was like, trying to sniff around in some shit, I dunno. And Nico, the idiot, starts losing his shit . “Come on, Diesel, fuckin’ dog. Come on.” Like, what the fuck good does that do? It’s a dog, man. So Nico pulls on the rope, like, seriously yanks the dog right up next to his face, and fucking head-butts it. I swear to God, man, he head-butts Diesel right on his nose. We were stunned, man. Like, did he just do that? And Diesel, man, he starts howling and crying, and I was like, I never felt sorry for that dog in my life, but that time just, damn.

That man is sick.

But if Nico was on weed, he’d be fine. Never see someone on weed head-butt a dog.

So yeah man, weed, no stress. No one gets worked up. All kinds of people do it here. Brown folks, ‘taters, Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, everybody.

I mean, I don’t think God really gets onto people for stuff like that, you know what I mean? Weed and all, or drinking, or women. Nah man, I think God is just like, who’s the best person on the inside, fuck the small stuff, right? I think so, anyway.

But yeah, I almost forgot to mention, women.

There’s this girl in class, or lots of them, I guess, but this one named Sarah. She is fine, man. I think I’ve seen her around Stovner a few times. When we went into the classroom that first day, I was like, holy shit, how fucking awesome it is that she’s in my class. She’s like two seats in front of me and looks so fine. Has that good color, dark hair, great body, all of it. I talk to her a little. The first day I walk up to her in the schoolyard, she’s having a cig during lunch hour, I say to her:

“Hey, how’s it going, cool we’re in the same class.” After that, we had cigarettes together a few times. Not all the time. I don’t like having all those other guys around. Forget it. Rashid, man, he’s always checking her out all the time. Those dogs just jump all over it. But when we have lunch hour and the others don’t, or when our class is over before theirs, I get to have a cig with her. It’s just been two times now, but she said yes both times, so you know, I think I’ll probably try to have more cigs with her.

This one teacher, though, is a real cunt. I am not kidding. Edvard is his name. He’s a racist, I swear. Always eyeballing me. Last year, whenever I would see him in the hallway, he was always throwing me nasty looks. And now, like, he looks at me like a damn criminal because I’m a couple minutes late to class. Never seen him give that look to ‘tater kids. When you’re brown, you notice shit. Just ask any brown kid. We know when some ‘tater looks at you in just that way, and we know what he’s thinking, too. And whenever I ask him something, he’s like, in this sarcastic voice, like he’s talking to some retard, “If you had been paying attention, then you’d know what to do.” Or: “Just think about it.”

Such bullshit. I am so good during class now. Follow along and everything. I mean, when I’m high, I don’t really pay attention then, but other than that, I try, but a lot of times it’s so hard, you don’t even know, man. Like when we have science and we’re supposed to make some stuff, I don’t even know what it’s called. Some substances have one number, other substances have this other number, and you’re supposed to add them together, but it’s not like math either, ‘cause it’s letters, like H2O + I dunno, N4O, you got me? I don’t understand dick, and my head gets hot and all that shit I already told you. Totally fucked up. So I start looking over at Sarah instead, and then that guy comes over to me with that look again and he’s like, “To work now, Jamal,” and I’m like, “Hey man, I don’t get this.” You know what he says? “Try harder.”

Fuckin’ jerk-off.

Well, that’s school.

Yeah, and by the way, listen. Don’t go and write stuff down like Jamal smokes weed in that research, got me? Get the cops knocking at my door and all.

You gotta do the #31# and hide the number, just with my name, ok?

Peace

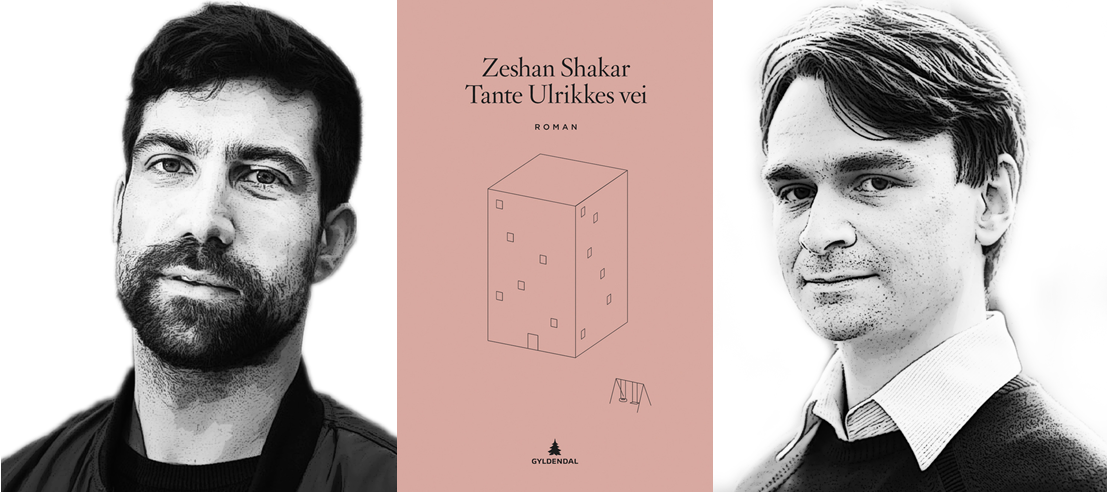

Zeshan Shakar was born and raised in Oslo. He has a master’s degree in political science from the University of Oslo, and works as a Special Advisor to the Deputy Mayor of Oslo. His first novel, Tante Ulrikkes vei, was published in September 2017 and won the prestigious Tarjei Vesaas Prize for the year’s best literary debut.

David M. Smith is a Norwegian-to-English translator. He holds a Humanities MA from the University of Chicago and a National Translator Accreditation from the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. In 2017, he was a Travel Fellow for the American Literary Translators Association Conference in Minneapolis. He is currently a Blog Editor at Asymptote, and starting fall 2018, he will be attending the University of Iowa MFA program in literary translation.

Published on April 17, 2018.