The Death of the Perpetrator: Interdisciplinary Reflections on the Cadavers of Criminals of Mass Violence, edited by Sévane Garibian

We have long known that the dead body is a powerful object. As anthropologist Katherine Verdery has noted, the corpse can be understood as a “symbolic vehicle” that is invested and divested of meaning in the making and reinvention of politics (1999). In contexts where tyrants have ruled by wielding systematic strategies of exclusion that seek to eliminate particular categories of persons and, by extension, their bodies, victims’ corpses are sites for unpacking and understanding the effects of these acts of violence. Disappeared bodies and recovered remains speak not only to the brutality of oppressive regimes, but also to the complex processes of meaning-making implicit in the production of new forms of historical knowledge. The attention paid to these bodies is both needed and necessary. However, by focusing primarily on one category of dead bodies, that of victims, we perhaps fail to consider how the cadavers of another, that of perpetrators, can mediate diverse narratives regarding violent pasts. When tyrants pass, their bodies can be hidden or celebrated. They can be mobilized or made static, memorialized or erased. In the face of resurgent demands for truth, justice, and reconciliation, what happens to perpetrators and their bodies reveals the twists and turns of complex and ongoing memory debates in the most unusual and, at times, uncomfortable of ways.

We have long known that the dead body is a powerful object. As anthropologist Katherine Verdery has noted, the corpse can be understood as a “symbolic vehicle” that is invested and divested of meaning in the making and reinvention of politics (1999). In contexts where tyrants have ruled by wielding systematic strategies of exclusion that seek to eliminate particular categories of persons and, by extension, their bodies, victims’ corpses are sites for unpacking and understanding the effects of these acts of violence. Disappeared bodies and recovered remains speak not only to the brutality of oppressive regimes, but also to the complex processes of meaning-making implicit in the production of new forms of historical knowledge. The attention paid to these bodies is both needed and necessary. However, by focusing primarily on one category of dead bodies, that of victims, we perhaps fail to consider how the cadavers of another, that of perpetrators, can mediate diverse narratives regarding violent pasts. When tyrants pass, their bodies can be hidden or celebrated. They can be mobilized or made static, memorialized or erased. In the face of resurgent demands for truth, justice, and reconciliation, what happens to perpetrators and their bodies reveals the twists and turns of complex and ongoing memory debates in the most unusual and, at times, uncomfortable of ways.

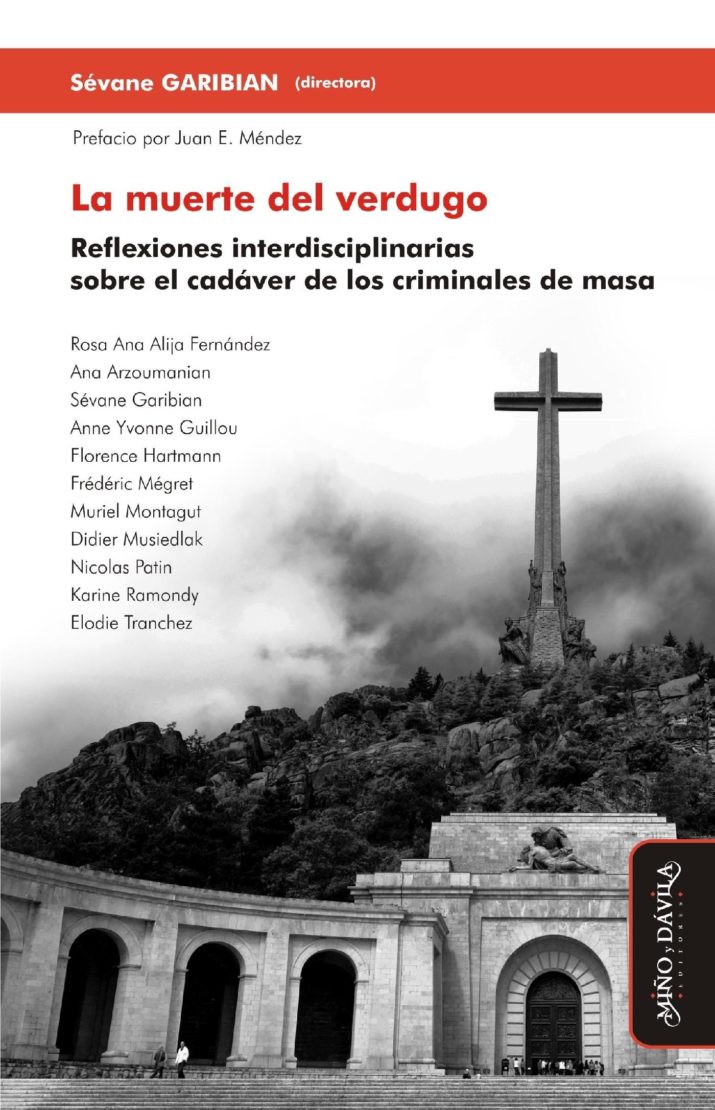

La muerte del verdugo, or The Death of the Perpetrator, edited by legal scholar Sévane Garibian brings together carefully crafted essays that seek to address these issues. Broad in scope and interdisciplinary in tone, the book examines the political, social, and symbolic lives of the bodies of Europe’s most singular tyrants, including Hitler, Franco, and Mussolini, who are placed side by side with analyses of other dictators and despots from Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia. Juxtaposing reflections from a range of disciplinary fields, including law, history, and anthropology, the volume focuses on three primary themes regarding perpetrators’ bodily remains: the ways in which authoritarian leaders have died and the contexts surrounding these events; the post-mortem treatment of their remains; and finally, the processes through which these once-violent bodies are remembered, memorialized, or even hidden from view. Paying close attention to how these remarkable cadavers are made heavy with meaning, each chapter demonstrates how the treatment of perpetrators’ remains, both in the past and the present, provides a path to understanding the intersections between memory, law, and the pursuit of justice. In this way, it is by considering the afterlives of the some of the world’s most remarkable oppressors that the book puts forth nuanced meditations regarding social and political life in the wake of tyranny.

The book is divided into three sections that individually correspond to particular kinds of perpetrator deaths. These types––natural or suspicious death, judicial execution, and extrajudicial assassination––are loosely aligned with three parallel categories of signification: death as escape (muerte-escapatoria), death as sentence (muerte-sentencia), and death as vengeance (muerte-venganza). While these death types structure how individual chapters are grouped and provide points of commonality and a temporal flow between disparate historical and political contexts, their correspondent categories of signification put forth a theoretical model that establishes flexible associations between death events and the current state of judicial institutions, divergent local ideas about rights and justice, and even conflicting stances regarding how the past should be remembered and narrated. In this construct, a tyrant’s natural death––like the cases of Spanish autocrat Francisco Franco and Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet analyzed by Rosa Ana Alija Fernández––or, a natural death read collectively as suspicious and murky, like the passing of Slobodan Milošević discussed by Florence Hartmann––point to how particular bodies escape the grip of justice and come to occupy a place of permanent impunity. In these cases, death is read as a kind of circumvention, whereby a movement towards accountability is interrupted. At the same time, “death-as-escape” also refers to the more symbolic dimension of tyrants’ dead bodies and the acts of remembrance, commemoration, and defamation that might accompany them. Within the conceptual frame of the muerte-escapatoria, a despot’s remains elude revenge, while also failing to attain complete celebrated forms of immortality.

In contrast, a judicial execution creates a very different category of signification, in which a public hearing––an atonement imposed by a third party––guarantees a more “orderly,” bureaucratic path towards justice. In these cases, as described in Nicolas Patin’s analysis of the executions of high-ranking members Nazi militants and in Ana Arzoumanian’s reading of the private, yet performative, execution and burial of Saddam Hussein, the law condemns villainous figures and their legacies. The “death-as-sentence,” however, does not demystify the immutable images of these criminals, nor does it prevent their cadavers from being invested with new symbolic meaning. Perhaps understandably, the law-sanctioned execution stands in stark contrast to the unofficial, extrajudicial, and often spectacular public assassination. As Garibian explains in her introductory chapter, this last death type ushers in the possibility of revenge, thereby situating the taking away of life as an act of vengeance. Drawing on a wide range of examples––from the assassination of Bin Laden analyzed by Frédéric Mégret and the execution of Muamar el Gadafi described by Muriel Montagut––this section posits that revenge is made available through the public stripping away of life. And yet, these executions, which stand outside the realm of the law, also open the door to the transformation of dead tyrants into symbolic martyrs. In other words, the death-as-vengeance formulation demonstrates how the rituals, that follow a perpetrator’s passing, “dishonor” his memory without guaranteeing the pacification of the lingering aftereffects of his violent regime.

These types and categories help structure a book that draws on examples that might otherwise feel like a collection of disparate case studies. At the same time, the careful sequence used to present the ten chapters where perpetrators’ deaths are examined in detail, draws readers’ attention to the different chronologies and points of rupture that precede the notions of rights, justice, and accountability that frequently circulate in contemporary debates on violence. This speaks to one of the book’s most salient characteristics: its ability to communicate the heterogeneous findings of a collective research endeavor and the development of an interdisciplinary, qualitative stance, both of which focus on “the death of the perpetrator” as a point of departure for understanding the cultural, judicial, historical, and political significance of the symbolic weight given to the worlds’ most remarkable tyrants and their bodily remains. In her provocative introduction, Garibian interestingly concludes that it is difficult, if not impossible, to establish a “systematic link of causality” between how tyrants die, the transformations that their bodies undergo, and the ways in which these remains are glorified or abandoned. In this sense, the types and categories previously described are not strict formulas, but rather a way of interrogating how pausing on the bodies of those responsible for acts of mass violence provide a rich entryway into understanding how memory and law––how truth and justice––overlap in profoundly important ways.

By placing tyrants and their dead bodies in an analytical limelight that seeks to compare across contexts and historical periods, this collection opens up a new arena of study that both complements and enhances literature that analyzes the political and social afterlives of those who fell victim to dictatorial, despotic regimes based on exclusion and elimination. Although broad in scope, this edited volume will be of interest to Europeanist scholars who examine issues of memory and memorialization; post-violence human rights; and emergent anti-fascist social movements. By turning readers’ attention to the afterlives of the masterminds behind these repressive regimes, the collection broadens scholarly debate about how bodies, even those belonging to former “executioners,” can play a central role in fomenting public debate about violence, exclusion, and their long-term aftereffects. Most importantly, it does so by suggestion themes and points of convergence, while also recognizing the inability to establish formulaic understandings regarding death and the processes of meaning-making that follow it. Given the current political climate in Europe and the world, where a new generation of victims and perpetrators are being called into being, this book makes important contributions to interdisciplinary debates about European Fascism, its legacy, and the movements that seek to prevent its resurgence.

Reviewed by Lee Douglas

La muerte del verdugo: Reflexiones interdisciplinares sobre el cadaver de los criminals de masa

Edited by Sévane Garibian

Publisher: Mino y Davila Editores (Argentina)

Papberback / 266 pages / 2016

ISBN: 9788416467631

Published on April 4, 2018.