This is part of our special feature Governing the Migration Crisis.

At the beginning of October 2013, a boat shipwrecked at the coast of Lampedusa and caused the death of approximately 350 asylum seekers. During his visit to Lampedusa shortly after it, the President of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso, demanded solidarity from the EU member states to help Italy deal with an increasing number of refugees arriving at the Italian coast.[1] In the aftermath of Europe’s migration crisis in 2015, the UN general secretary Ban-Ki Moon, stated that this crisis is not a crisis of numbers, but a crisis of solidarity.[2] In his book “the new odyssey,” the former Guardian journalist Patrick Kingsley, also criticized that during the migration crisis, Europe had mainly forgotten one of its guiding principles and values, namely solidarity.[3] Even the Eurosceptic governments in Poland and Hungary picked up the term and called for flexible solidarity[4] mechanisms in the EU. These examples raise questions regarding how to make sense of these divers, but unified claims for solidarity and what do actors actually mean by the term solidarity?

My claim is that solidarity should be understood as a “contested concept”[5] which is disputed by actors in regard to the notions and limits of solidarity. There is no generally accepted meaning of solidarity. In fact, actors deploy their own rationale to make sense of the concept of solidarity and discursively construct their version of solidarity to deal with migration issues and refugees. Notions of solidarity can range from political solidarity as new institutional settings or laws that should distribute the fair share of refugees among EU member states, cultural solidarity, which focuses on shared norms and values as a foundation to act in solidarity, or social solidarity, which emphasizes measures of social policy or social support by volunteers or neighbors in order to help migrants and refugees. Differentiating solidarity based on the meanings helps understand what the concept means, which implications it bears, and how various types of solidarity are used in the discursive struggles about Europe’s migration crisis.

Moreover, I will argue that earlier events and conflicts on migration and refugee issues should be taken into consideration to fully understand Europe’s migration crisis and the calls for solidarity in 2015. In the following article, I take a closer look at the German media debate because Germany is highly influential within the EU institutions and it was strongly affected by the migration crisis in 2015. Thus, analyzing the elite discourse in German newspapers demonstrates how solidarity is framed and which (party) actors are involved in the debate. The EU has tried to establish a Common European Asylum System (CEAS) in the last fifteen years[6], EU member states strongly shape the refugee and asylum policies in the EU.[7] Moreover, party ideology and government participation influence the claims of party actors to argue for or against solidarity and which type of solidarity they prefer.[8] As a result, these claims shape the public debate. Therefore, the following analysis of the discourse focuses on the party actors and their claims.[9] To illustrate which actors use what kind of concept, I visualize the discourse by deploying the discourse network analysis approach.[10]

2013: From the Mediterranean to “Lampedusa in Hamburg”

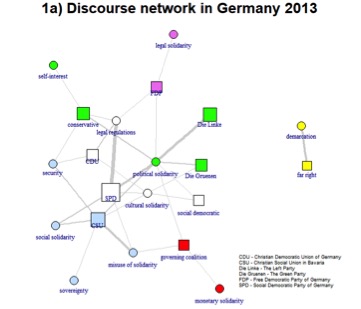

Figure 1a (below) visualizes the whole discourse in German newspapers in 2013. The squares are party actors that made a claim in newspaper articles. The German parties were coded by name while all the other party politicians from other countries were coded due to their party family affiliation. The circles represent concepts that party actors used to justify their position. Parties are connected to concepts, because they have used this concept in (at least) one statement in 2013. Different actors can refer to a various concepts in their claims. Based on these claims, the network is computed and visualized with the R package igraph.[11]

The German discourse on solidarity in 2013 was affected by international incidents such as the Lampedusa accident in October, but also by local and national conflicts. From the summer of 2013 (until spring 2014) the local social democratic government (SPD) in the city-state of Hamburg was in conflict with several civil society and activists groups, the church and the opposition of the Left and the Green party about “Lampedusa in Hamburg”. This is a group of refugees who came to Hamburg and claimed asylum. Since many of them entered the EU in Italy first, the SPD argued that based on the Dublin Agreement, they have to go back to Italy and that Hamburg is not responsible for them. Some pastors granted safe-havens in churches (Kirchenasyl) giving asylum seekers a refuge from pursuit or persecution, preventing deportation and that allowed them to stay in Hamburg temporarily. The thick tie between the Left party and political solidarity shows the effort to find political solution to accept refugees to the asylum procedure in Hamburg. The Hamburg government strongly argued from a legal perspective (see the thick tie between the SPD and the concept legal regulations in figure 1a), referred to necessary changes on the European level and was not willing to reconsider their position. On the other hand, German newspapers reported about neighbors providing food and clothes for refugees or lawyers and physicians giving advices for free which can be understood as social solidarity on the local level.

The relevance of this conflict underlines that the migration crisis is Europeanized in terms of issue framing, but not in regard to the actor constellation, because German parties dominate the discourse.

Note: The discourse network has two types of nodes: Circles are concepts, squares are party actors. The German parties are named; all the other parties are grouped into party families. Concepts were identified in an inductive-deductive process of coding selected newspaper articles. The size of the nodes is based on hub centrality scores.[12] The bigger the node is and is connected to other bigger nodes, the more influential is an actor or concept in the network. The edge width shows the number of references to a concept of one actor. The colors in the network display subgroups within the network, which were identified by using a community detection algorithm in the R package igraph. Same colored nodes represent closely linked actors and concepts. Number of nodes: 21; number of edges: 50.

The refugee shipwreck at the coast of Lampedusa at the beginning of October 2013 caused a media and political outcry. Afterwards, the Italian government started the Marine and Coast Guard mission ‘Mare Nostrum’ to rescue migrants. The following Frontex mission ’Triton’ was minor and focused more on security, border control and stopping irregular migration by fighting against human trafficking. Retrospectively, one claim by Angela Merkel is remarkable at this time. As a public reaction to this accident, Italian as well as German social democrats (SPD) demanded that the EU should introduce a system of distribution to share financial burdens and refugees. The German Chancellor Merkel, however, refused such proposals as the Sueddeutsche Zeitung reports:

The German Chancellor Angela Merkel (CDU) harshly rejected those ideas which were also presented by her Austrian counterpart Werner Feymann (social democrat) in Brussels. Relocating asylum seekers among the EU member states is often demanded again and again, said the Chancellor. She thinks, however, that the discussion about the refugee policy should be based on the existing legal regulations (Sueddeutsche Zeitung, October 26th 2013).

In the wake of the migration crisis in 2015, Angela Merkel and other German politicians criticized exactly this position and demanded a new system of fair burden-sharing among the EU member states. At that time though, many states hesitated to agree and especially the Visegárd group members (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, and Slovakia) refused to create a mandatory solidarity mechanism.

To sum up, the discourse in 2013 was less focused on specific concepts of solidarity, but rather illustrates the contestation between solidary actions with refugees or EU member states and security and legal issues to argue against solidarity.

2014: A solidarity mechanism is needed

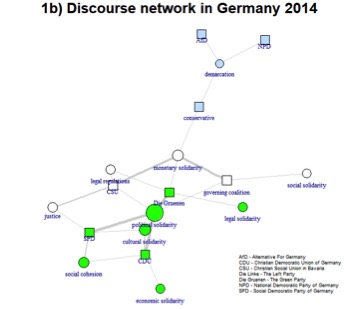

The German media debate was heavily influenced by the Syrian war and the increasing amount of refugees and migrants coming to Europe. Especially German local authorities stated that there are no more capacities to accommodate a higher amount of refugees. In this regard, the regional German party CSU tried to intertwine the debate about refugees with the so called “poverty migration” from Eastern Europe and argued that Germany should be more restrictive to migration. SPD and Green politicians as well as European commissioners referred to official statistics in this case and criticized the inaccurate claims of the CSU. Network figure 1b) shows less subgroups within the network as the previous discourse network. An explicit right-wing subgroup is detected (light blue), a big CDU/SPD/Greens subgroup (green) which mainly focuses on political solidarity and a more diffuse subgroup (white) which includes various concepts. This network structure represents the different perspectives on migration and refugee issues in 2014.

Note: same network description applies as in figure 1a), Number of nodes: 18; number of edges: 40.

The conflictual situation in the Middle east – civil war in Syria, conflict between Kurds, IS, the Iraqi and the Turkish army – not only created a debate about a military intervention from the ‘West’, but also a discussion about special support for Syrians and Christians from the Middle East and the minority Yazidi. While almost every claimant declared solidarity with these groups, the solutions reached from specific quotas for Syrians and Christians to increased financial help for local or regional camps and organizations (see the nodes monetary solidarity and economic solidarity) as well as establishing European programs to provide a common and European-wide political action in regard to migration, asylum and integration (see the node political solidarity). Additionally, some actors explicitly argued for the appointment of a European Commissioner for refugee and migration affairs, which could be the counterpart to the UNHCR High Commissioner on the European level.

In contrast to the pro-solidarity arguments, anti-solidarity claims were made to argue against any border-crossing of people. This concept goes hand in hand with racist and nationalist arguments as well as violent attacks against refugees, migrants or volunteers:

March 14th 2014, refugees have been living in Hellersdorf [Neighborhood in Berlin, S.W.] for seven months: Two residents are chased through the streets by offenders and hardly make it into the residence. Six men try to follow them into the house, throw beer bottles, threaten them – and leave the crime scene. Unrecognized. (Sueddeutsche Zeitung, March 26th 2014).

As shown in the discourse network figure 1b), especially right-wing parties and conservative politicians use demarcation justifications to position themselves against solidarity. Such actions, however, have not dominated the German elite discourse. To sum up again, political solidarity mechanisms were strongly debated among the politicians. Many actors agreed that dealing with an increasing number of asylum seekers needs a European mechanism to share the responsibility among the EU member states. Besides some explicit exclusionary claims, the elite party discourse was mostly in favor of showing solidarity in one way or another.

“The (long) summer of migration” in 2015

2015 was a turbulent year in terms of immigration and asylum seeking. More than one million migrants and refugees, coming from conflict zones in the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia, challenged the EU border regime, the Dublin agreements and revealed the “asymmetric way”, in which the EU migration and asylum policy was developed.[13]

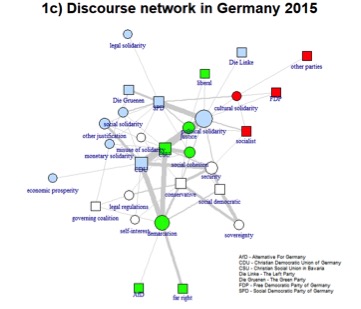

The figure 1c) does show a large and strongly connected discourse networks with the most actor and concepts nodes. There are again several subgroups within the network. Those display a group of (green) nodes that are arranged around the big node demarcation and another large group of nodes (white) that are grouped around the other big node political solidarity. The smaller groups are focused either on security (white nodes) or on cultural solidarity (red subgroup). These four subgroups illustrate the contestation of solidarity in regard to pro- or anti-solidarity justifications which are used in the discourse in 2015. It also shows that different types of solidarity have gained attention and are constructed by different parties.

Note: same network description applies as in figure 1a), Number of nodes: 29; number of edges: 137.

The public attention on migration issues and solidarity was very salient in the long summer of migration, starting from August until the beginning of October 2015.[14] On August 28th, a truck with several dozen dead migrants was found who were locked in the vehicle on a highway in Austria inducing a public outcry. In reaction to that and the diminishing humanitarian situation in Hungary, German Chancellor Angela Merkel said on August 31st: ”We will manage it and where something hinders us, it must be overcome”[15] which later became a key slogan in the debate. Lastly, on September 3rd, a picture from the drowned three-year-old boy Alan Kurdi, lying dead on a beach at the Turkish coast, received a lot of media attention and produced public reactions about the deadly journey of migrants and refugees crossing the Mediterranean. These events created a high public awareness and huge media coverage on refugee issues and popularized the call for solidarity. Even though politicians’ already debated solidarity before these serious events as the following statement by a German politician illustrates:

“We need more solidarity. We need more humanity,” claimed Michael Roth, the German Minister of State for Europe, in Luxembourg on Tuesday. “We are very, very open to develop a mechanism of solidarity which commits all member states to do more than before,” he emphasized (Sueddeutsche Zeitung, June 24th 2015).

The mentioned idea of European political solidarity refers to two aspects: strengthening the bonds among the member states and marking the exclusion of refugees. By doing so, such statements demonstrate the exclusionary effect of solidarity claims. Migrants and refugees are not subjects in these claims and justifications, but EU member states are addressed. Nonetheless, political solidarity is the main justification (see also the big node in the figure 1c) of how to engage politically in the migration crisis. Among the party actors, creating new solidary institutional mechanisms is perceived as the most crucial aspect in dealing with the migration crisis and establishing modes of cooperation among the EU member states.

Demarcation and security frames also play an important role (see the nodes demarcation and security) in the discourse in 2015.[16] Actors argue for national fences and border control and migration movements are constructed as threats to national sovereignty as well as to the stability of the European community (see also the nodes sovereignty and social cohesion). Instead of showing solidarity with refugees the claim for solidarity is used to justify security measures at the national and European borders. The following statement by the former Polish Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz exemplifies this:

Warsaw wants to prevent a revision of asylum law based on the population of the EU member states. Until now Poland receives only few refugees in relation to its population size – in 2014 only 114 Syrians have applied for asylum. It is not surprising that the head of government Ewa Kopacz primarily insists on better border security in the Mediterranean at the EU summit in Brussels. “Our solidarity primarily rests upon strongly supporting Frontex. We will send our border police officers” (Die Welt newspaper, April 25th 2015).

This statement and the salience of sovereignty, security, demarcation or social cohesion demonstrate that solidarity is highly contested among the political parties. Actors argue for solidarity to pursue their own interest. In this case, strategically not arguing against solidarity, but re-framing solidarity that it fits into a security justification. While the justifications demarcation and security were almost exclusively used by far right and right-conservative politicians so far, in 2015 both concepts were used more widely. Smugglers and human trafficking are reference points to argue against solidarity and emphasize security threats and national sovereignty.[17]

The contrasting justifications to solidarity demonstrate that even though claims for solidarity are the most frequent ones, the contestation of solidarity is an essential part of the discourse as well. These are two sides of the same coin: Political solidarity is proposed to set up a European mechanism to take in refugees or fairly relocate refugees among EU member states. On the other side the Schengen Agreement is questioned and the renationalization of border control and refugee policy is favored.

Conclusion: Contested Solidarities in times of crisis

Solidarity was one of the buzzwords in Europe’s migration crisis. The analysis of the German discourse from 2013 to 2015 has shown that political solidarity is the central concept. In the light of refugee boat accidents and increasing migrant fatalities in the Mediterranean, the shortcomings of the EU migration and refugee policy become obvious. The Dublin III regulation demands that the first country of entry of asylum seekers have to deal with their asylum procedure. Hence, the Southern European border countries Italy and Greece face the highest ‘burden’ to deal politically and socially with those human beings who fled from persecution, civil wars and terrorism. The consequence in regard to CEAS is, as Jürgen Bast states: “There is no asylum system based on solidarity”[18]. This perception seems to be shared by many national and European actors, because they argued for a European solidarity mechanism in the last years. In September 2015, the European Commission[19] has advocated introducing a relocation system for 160,000 refugees among the EU member states, but this proposal has not been successfully implemented. Many states, not only the often blamed Visegrád countries (Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia), have refused to take in the promised number of refugees from Italy and Greece until now . The recent ruling by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) that the challenge of the EU refugee quota policy by Poland and Hungary is not valid[20], vividly demonstrates that the call for solidarity is highly contested.

Introducing the solidarity mechanism for the relocation program is, one the one hand, an international political solidary action, because this helps the affected EU member states to deal with the sheer amount of people, reduces the delays of the asylum recognition procedure and could be a cornerstone in a further integrated EU migration and asylum policy in the future. On the other hand, the expressed solidarity is actually an internal solidarity, because it addresses solidarity within the EU and on the nation-state level. External Solidarity with refugees outside the EU is less claimed. Furthermore, the voices of refugees and asylum seekers are often missing in the discourse. Even more problematic is that the EU-Turkey deal or the new border cooperation with militias in Libya or the armed forces in Niger and Mali draw an anti-solidarity picture of EUs migration and asylum policy.

On May 9th 1950, Robert Schuman said that Europe “will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity”[21]. In his speech Schuman proposed the European Coal and Steel Community which was one of the key steps towards the current European Union. His statement about solidarity can be apprehend as a crucial normative reminder to the current situation that solidarity is nothing that should be ignored, but something that has to be actively created – internally within the European Union and externally with people in need.

Stefan Wallaschek is a PhD fellow at the University of Bremen, Bremen International Graduate School of Social Sciences (BIGSSS) in Germany. His dissertation is on the politics of solidarity: comparing the Eurozone crisis and Europe’s migration crisis. His research interests are European politics, solidarity research, political communication, migration and refugee studies as well as discourse network analysis. Parts of the analysis in this blog post will be published in the chapter “The Politics of Solidarity in Europe’s Migration Crisis: Media Discourses in Germany and Ireland in 2015” in Jenichen, Anne/Liebert, Ulrike (eds.): Europeanisation and Renationalisation. Learning from Crises for Innovation and Development. Opladen: Barbara Budrich, Forthcoming.

Photo: MAGDEBURG, GERMANY: On the refugee ship “Al-hadi Djumaa” there are 70 bronze figures by the Danish artist Jens Galschiøt. An art project about escape and expulsion, Mattis Kaminer | Shutterstock

References:

Ardittis, Solon. “Flexible Solidarity: Rethinking the EU’s Refugee Relocation System after Bratislava.” LSE EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, September 21, 2016. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/09/21/rethinking-refugee-system-after-bratislava/.

Ban, Ki-Moon. “Statement Attributable to the Secretary-General on Recent Refugee/Migrant Tragedies,” August 28, 2015. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2015-08-28/statement-attributable-secretary-general-recent-refugeemigrant.

Barroso, José Manuel. “Statement by President Barroso Following His Visit to Lampedusa.” European Commission Press Release Database, October 9, 2013. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-13-792_en.htm.

Bast, Jürgen. “‘In Europe There Is No Solidarity in Terms of the Asylum System.’” Verfassungsblog, October 21, 2013. http://verfassungsblog.de/in-europe-there-is-no-solidarity-in-terms-of-the-asylum-system/.

Chetail, Vincent. “Looking Beyond the Rhetoric of the Refugee Crisis: The Failed Reform of the Common European Asylum System.” European Journal of Human Rights 1, no. 5 (2016): 584–602.

Closa, Carlos, and Aleksandra Maatsch. “In a Spirit of Solidarity? Justifying the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) in National Parliamentary Debates.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52, no. 4 (July 2014): 826–42. doi:10.1111/jcms.12119.

Csárdi, Gábor, and Tamás Nepusz. “The Igraph Software Package for Complex Network Research. Version 1.0.1.” InterJournal Complex Systems (2006): 1695.

European Commission. “Refugee Crisis: European Commission Takes Decisive Action – Press Release,” September 9, 2015. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-5596_en.htm.

Gallie, Walter Bryce. “Essentially Contested Concepts.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 56 (1956): 167–98.

Greussing, Esther, and Hajo G. Boomgaarden. “Shifting the Refugee Narrative? An Automated Frame Analysis of Europe’s 2015 Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43, no. 11 (August 18, 2017): 1749–74. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1282813.

Jäckle, Sebastian, and Pascal D. König. “The Dark Side of the German ‘Welcome Culture’: Investigating the Causes behind Attacks on Refugees in 2015.” West European Politics 40, no. 2 (March 4, 2017): 223–51. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1215614.

Kanter, James. “E.U. Countries Must Accept Their Share of Migrants, Court Rules.” New York Times, September 7, 2017.

Kasparek, Bernd, and Marc Speer. “Of Hope. Hungary and the Long Summer of Migration.” Bordermonitoring.Eu, September 9, 2015. http://bordermonitoring.eu/ungarn/2015/09/of-hope-en/.

Kingsley, Patrick. The New Odyssey: The Story of Europe’s Refugee Crisis. London: Guardian Books, 2016.

Kleinberg, Jon M. “Authoritative Sources in a Hyperlinked Environment.” Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery 46, no. 5 (1999): 604–32.

Leifeld, Philip. Policy Debates as Dynamic Networks: German Pension Politics and Privatization Discourse. Schriften Des Zentrums Für Sozialpolitik Bremen, Band 29. Frankfurt a. M.: Campus, 2016.

Leifeld, Philip, and Sebastian Haunss. “Political Discourse Networks and the Conflict over Software Patents in Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 51, no. 3 (May 2012): 382–409. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02003.x.

Merkel, Angela. “Sommerpressekonferenz von Bundeskanzlerin Merkel. Thema: Aktuelle Themen der Innen- und Außenpolitik,” August 31, 2015. https://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/DE/Mitschrift/Pressekonferenzen/2015/08/2015-08-31-pk-merkel.html.

Monar, Jörg. “Justice and Home Affairs.” In The Oxford Handbook of the European Union, edited by Erik Jones, Anand Menon, and Stephen Weatherhill, 613–626. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press, 2014.

Schuman, Robert. “The Schuman Declaration – 9 May 1950.” May 9, 1950. https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/symbols/europe-day/schuman-declaration_en.

Stjernø, Steinar. Solidarity in Europe: The History of an Idea. Re-Printed in 2009. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005.

Wallaschek, Stefan. “The Politics of Solidarity in Europe’s Migration Crisis: Media Discourses in Germany and Ireland in 2015.” In Europeanisation and Renationalisation. Learning from Crises for Innovation and Development, edited by Anne Jenichen and Ulrike Liebert. Opladen: Barbara Budrich, Forthcoming.

Wilde, Pieter de, Michael Zürn, and Ruud Koopmans. “The Political Sociology of Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism: Representative Claims Analysis.” WZB Discussion Paper SP IV 2014-102, 2014. https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/2014/iv14-102.pdf.

Zaun, Natascha. “Why EU Asylum Standards Exceed the Lowest Common Denominator: The Role of Regulatory Expertise in EU Decision-Making.” Journal of European Public Policy 23, no. 1 (January 2, 2016): 136–54. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1039565.

[1] José Manuel Barroso, “Statement by President Barroso Following His Visit to Lampedusa,” European Commission Press Release Database, October 9, 2013, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-13-792_en.htm.

[2] Ki-Moon Ban, “Statement Attributable to the Secretary-General on Recent Refugee/Migrant Tragedies,” August 28, 2015, https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2015-08-28/statement-attributable-secretary-general-recent-refugeemigrant.

[3] Patrick Kingsley, The New Odyssey: The Story of Europe’s Refugee Crisis (London: Guardian Books, 2016).

[4] Solon Ardittis, “Flexible Solidarity: Rethinking the EU’s Refugee Relocation System after Bratislava,” LSE EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, September 21, 2016, http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/09/21/rethinking-refugee-system-after-bratislava/.

[5] Walter Bryce Gallie, “Essentially Contested Concepts,” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 56 (1956): 167–98.

[6] Vincent Chetail, “Looking Beyond the Rhetoric of the Refugee Crisis: The Failed Reform of the Common European Asylum System,” European Journal of Human Rights 1, no. 5 (2016): 584–602; Jörg Monar, “Justice and Home Affairs,” in The Oxford Handbook of the European Union, ed. Erik Jones, Anand Menon, and Stephen Weatherhill (Oxford: Oxford Univ Press, 2014), 613–626.

[7] Natascha Zaun, “Why EU Asylum Standards Exceed the Lowest Common Denominator: The Role of Regulatory Expertise in EU Decision-Making,” Journal of European Public Policy 23, no. 1 (January 2, 2016): 136–54, doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1039565.

[8] Carlos Closa and Aleksandra Maatsch, “In a Spirit of Solidarity? Justifying the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) in National Parliamentary Debates,” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52, no. 4 (July 2014): 826–42, doi:10.1111/jcms.12119; Steinar Stjernø, Solidarity in Europe: The History of an Idea, Re-printed in 2009 (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

[9] The selected newspaper articles in two German quality daily newspapers were coded by using the political claims analysis method, see Pieter de Wilde, Michael Zürn, and Ruud Koopmans, “The Political Sociology of Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism: Representative Claims Analysis,” WZB Discussion Paper SP IV 2014-102, 2014, https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/2014/iv14-102.pdf. I identified 590 claims in the time frame 2013-2015. Among others, I coded the party affiliation of every claimant. If the actor had no party affiliation, I coded “no party affiliation”. Those claimants were excluded from the discourse network, because otherwise, the actor ‘no party affiliation’ would have been the biggest node in the network without being reasonably interpretable.

[10] Philip Leifeld, Policy Debates as Dynamic Networks: German Pension Politics and Privatization Discourse, Schriften Des Zentrums Für Sozialpolitik Bremen, Band 29 (Frankfurt a. M.: Campus, 2016); Philip Leifeld and Sebastian Haunss, “Political Discourse Networks and the Conflict over Software Patents in Europe,” European Journal of Political Research 51, no. 3 (May 2012): 382–409, doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02003.x.

[11] Gábor Csárdi and Tamás Nepusz, “The Igraph Software Package for Complex Network Research. Version 1.0.1,” InterJournal Complex Systems (2006): 1695.

[12] Jon M. Kleinberg, “Authoritative Sources in a Hyperlinked Environment,” Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery 46, no. 5 (1999): 604–32.

[13] Monar, “Justice and Home Affairs,” 620.

[14] Bernd Kasparek and Marc Speer, “Of Hope. Hungary and the Long Summer of Migration,” Bordermonitoring.Eu, September 9, 2015, http://bordermonitoring.eu/ungarn/2015/09/of-hope-en/.

[15] Angela Merkel, “Sommerpressekonferenz von Bundeskanzlerin Merkel. Thema: Aktuelle Themen der Innen- und Außenpolitik,” August 31, 2015, https://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/DE/Mitschrift/Pressekonferenzen/2015/08/2015-08-31-pk-merkel.html.

[16] Esther Greussing and Hajo G. Boomgaarden, “Shifting the Refugee Narrative? An Automated Frame Analysis of Europe’s 2015 Refugee Crisis,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43, no. 11 (August 18, 2017): 1749–74, doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1282813; Sebastian Jäckle and Pascal D. König, “The Dark Side of the German ‘Welcome Culture’: Investigating the Causes behind Attacks on Refugees in 2015,” West European Politics 40, no. 2 (March 4, 2017): 223–51, doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1215614.

[17] see also Stefan Wallaschek, “The Politics of Solidarity in Europe’s Migration Crisis: Media Discourses in Germany and Ireland in 2015,” in Europeanisation and Renationalisation. Learning from Crises for Innovation and Development, ed. Anne Jenichen and Ulrike Liebert (Opladen: Barbara Budrich, Forthcoming).

[18] Jürgen Bast, “‘In Europe There Is No Solidarity in Terms of the Asylum System,’” Verfassungsblog, October 21, 2013, http://verfassungsblog.de/in-europe-there-is-no-solidarity-in-terms-of-the-asylum-system/.

[19] European Commission, “Refugee Crisis: European Commission Takes Decisive Action – Press Release,” September 9, 2015, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-5596_en.htm.

[20] James Kanter, “E.U. Countries Must Accept Their Share of Migrants, Court Rules,” New York Times, September 7, 2017.

[21] Robert Schuman, “The Schuman Declaration – 9 May 1950,” May 9, 1950, https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/symbols/europe-day/schuman-declaration_en.

Published on October 2, 2017.