Translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky.

This is part of our special feature Governing the Migration Crisis.

One Thursday in late August, ten men gather in front of Berlin’s Town Hall. According to news reports, they’ve decided to stop eating. Three days later they decide to stop drinking too. Their skin is black. They speak English, French, Italian, as well as other languages that no one here understands. What do these men want? They are asking for work. They want to support themselves by working. They want to remain in Germany. Who are you, they’re asked by police officers and various city employees who’ve been called in. We won’t say, the men reply. But you have to say, they’re told, otherwise how do we know whether the law applies to you and you’re allowed to stay here and work? We won’t say who we are, the men say. If you were in our shoes, the others respond, would you take in a guest you don’t know? The men say nothing. We have to verify that you’re truly in need of assistance. The men say nothing. You might be criminals, we have to check. They say nothing. Or just freeloaders. The men are silent. We’re running short ourselves, the others say, there are rules here, and you have to abide by them if you want to stay. And finally they say: You can’t blackmail us. But the men with dark skin don’t say who they are. They don’t eat, they don’t drink, they don’t say who they are. They simply are. The silence of these men who would rather die than reveal their identity unites with the waiting of all these others who want their questions answered to produce a great silence in the middle of the square called Alexanderplatz in Berlin. Despite the fact that Alexanderplatz is always very loud because of the traffic noise and the excavation site beside the new subway station.

Why is it that Richard, walking past all these black and white people sitting and standing that afternoon, doesn’t hear this silence?

He’s thinking of Rzeszów.

A friend of his, an archaeologist, told him about discoveries made during the tunneling operation at Alexanderplatz and invited him to visit the excavation site. He has time enough on his hands, and swimming in the lake isn’t an option, because of this man. His friend explained that there used to be an extensive system of cellars all around Town Hall. Subterranean vaults that housed a marketplace during the Middle Ages. While people waited for a hearing, an appointment, a ruling, they would go shopping, much as they do today. Fish, cheese, wine—everything that keeps better chilled—was sold in these catacombs.

Just like in Rzeszów.

As a student in the 1960s, Richard would sometimes sit on the edge of the Neptune Fountain between two lectures, his trouser legs rolled up, his feet in the water, book in his lap. Even then, unbeknownst to him, these hollow spaces were there beneath him, only a few yards of earth separating them from his feet.

Several years ago, back when his wife was still alive, the two of them had visited the Polish town of Rzeszów on one of their vaca- tions—a town with an elaborate system of tunnels running beneath it, dating from the Middle Ages. Like a second town, invisible to the casual observer, this labyrinth had grown beneath the earth, a mirror image of the houses visible aboveground. The cellar of ev- ery house gave access to this public marketplace that was lit only by torches. And when there was a war up above, the residents of the town would retreat underground. Later, in the time of fascism, Jews took refuge here until the Nazis hit on the idea of filling the subterranean passageways with smoke.

Rzeszów.

But the rubble-filled vaults beneath Berlin’s Town Hall escaped detection even by the Nazis, who contented themselves with flooding the subway tunnels in the final days of the war. Probably to drown their own people who had fled underground, taking refuge from the Allies’ air raids. There you go again, cutting off your nose to spite your face.

Have any of the men collapsed yet? asks a young woman holding a microphone, behind her a colossus has a camera on his shoulder. No, one of the policemen says. Are they being force-fed? So far, no, the policeman says, see for yourself. Have any of them been sent to the hospital? I think one was yesterday before my shift, another man in uniform says. Could you tell me which hospital? No, we’re not allowed to say. But then I can’t place my story. That’s too bad, the first policeman says, I’m afraid there’s nothing we can do about that. The young woman says: If nothing special happens, I can’t make a story out of it. Sure, makes sense, the policeman says. No one will want to run it. The other officer says: There might be some action later today, maybe in the evening. The young woman: All I have left is an hour, tops. There has to be time for editing. Makes sense, the man in uniform says and grins.

Richard doesn’t glance over at Town Hall two hours later either when he’s walking again past the train station, he’s looking at the big fountain on the left, its various terraces arranged like a staircase leading up to the base of the TV tower. Built during Socialist times and bubbling over with water summer after summer, it was the perfect spot for happy children to test their mettle, balancing their way across the stone rows separating the fountain’s pools as their laughing, proud parents looked on, and both children and parents alike would now and then gaze up at the tower’s silvery sphere, en- joying the vertigo: It’s falling! It’s falling right on top of us! Three hundred sixty-five meters to its tip, measuring out the days of an entire year, a father says, and: No, it’s not falling, it just looks that way, a mother says to her dripping children. A father tells his children—but only if they really want to hear it—the story of the construction worker who fell from the very top of the tower as it was being built, but because it’s so tall, it took the man a very long time to fall to the bottom, and meanwhile the people who lived in the buildings down below were able to drag mattresses outside while the worker was still falling, an entire huge pile of mattresses while he fell and fell, and the pile was finished just in time for the worker to arrive at the end of his fall, and he landed as softly as the princess and the pea in the fairy tale and got right back to his feet without a scratch on him. The children delight in this miracle that saved the worker, and now they’re ready to go back to playing. At the Alexanderplatz fountain, summer after summer, humankind appeared to be in fine fettle and content—the sort of condition generally promised only for the future, for that distant age of utter contentment known as Communism that mankind would eventually make its way to via a sort of staircase of progress leading into dazzling, astonishing heights, a state to be achieved in the next hundred, two hundred, or at the very most three hundred years.

But then, defying all expectations, the East German government that had commissioned this fountain suddenly disappeared after a mere forty years of existence along with all its promises for the future, leaving behind the staircase-shaped fountain to bubble away on its own, and bubble it did, summer after summer, reaching to dazzling, astonishing heights while adventurous children continued to balance their way across, admired by their laughing, proud parents. What can a picture like this that’s lost its story tell us? What vision are these happy people advertising now? Has time come to a standstill? Is there anything left to wish for?

The men who would rather die than say who they are have been joined by sympathizers. A young girl has sat down cross-legged on the ground next to one of the dark-skinned men and is conversing with him in a low voice, nodding now and then, rolling herself a cigarette. A young man is arguing with the policemen: It’s not as if they’re living here, he says, and the policeman replies: Well, that wouldn’t be permitted. Exactly, the young man says. The black men are crouching or lying on the ground, some of them have spread out sleeping bags to lie on, others a blanket, others nothing at all. They’re using a camping table to prop up a sign. The sign leaning against it is a large piece of cardboard painted white, on which black letters spell out in English: We become visible. Be- neath this, in smaller green letters, someone has written the Ger- man translation with a marker. Was it the young man or the girl? If the dark-skinned men were to glance in Richard’s direction at just this moment, all they would see is his back making a beeline for the train station, he is dressed in a blazer despite the heat, and now he vanishes among all the other people, some of whom are in a hurry and know exactly where they’re going, while others meander, holding maps, they’re here to see “Alex,” the center of that part of Berlin long known as the “Russian zone” and still often referred to as the “Eastern zone” in jest. If these silent men were then to raise their eyes, they would behold—as a backdrop to the bustle of the square and elevated one floor above—the windows of the Fitness Center, located beside the tower’s plinth under an extravagantly pleated canopy. Behind the windows they would see people on bicycles and people running, bicycling and running toward the enormous windows hour after hour, as if trying to ride or run across to Town Hall as quickly as possible, either to join them, the men with dark skin, or to approach the policemen to declare their solidarity with one or the other side, even if it would mean bursting through the windows to fly or leap the last bit of the way. But obviously both the bicycles and the treadmills are firmly mounted in place, and those exercising on them exert themselves without any forward progress. It’s quite possible that these fitness-minded individuals can observe everything happening on Alexanderplatz in front of them, but they probably wouldn’t be able to read, say, the words on the sign—for that, they’re too far away

Jenny Erpenbeck was born in East Berlin in 1967. New Directions publishes her books The Old Child & Other Stories, The Book of Words, and Visitation, which NPR called “a story of the century as seen by the objects we’ve known and lost along the way.”

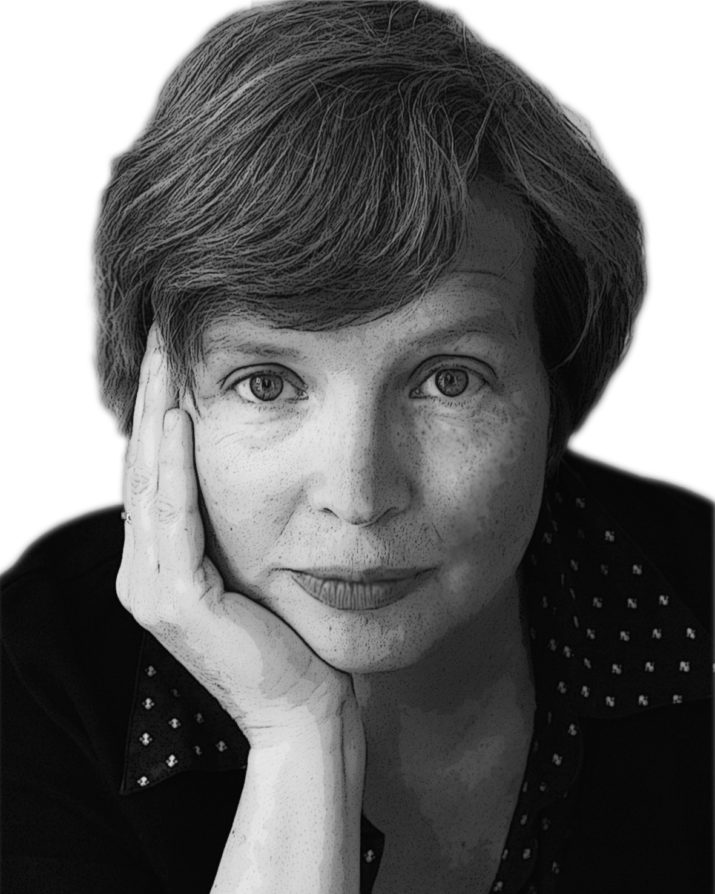

Susan Bernofsky is the acclaimed translator of Hermann Hesse, Robert Walser, and Jenny Erpenbeck, and the recipient of many awards, including the Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize and the Hermann Hesse Translation Prize. She teaches literary translation at Columbia University and lives in New York.

This excerpt from Go, Went, Gone is published by permission of New Directions Publishing. Copyright © 2015 by Albrecht Knaus Verlag, a division of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH, München, Germany Translation copyright © 2017 by Susan Bernofsky.

Published on October 2, 2017.