Translated from the Danish by Gaye Kynoch.

This is part of our special feature Governing the Migration Crisis.

And then, just a moment later, as if by the snapping of fingers, the wedding that is, in comparison with the wedding in The Godfather, modest, but nonetheless has the same opulence and lighting, the town hall, which usually reduces even the most beautiful couple and the deepest love to an errand at the post office, is, the moment they enter, transformed into a church, the municipal official is their and thereby God’s humble servant, who on His behalf blesses them, her, not in white, she is not an ingenuous virgin, she is already an experienced queen, wearing a plain rosemary-gray summer dress with a shiny narrow belt around a wonderfully hour-glass waist, him in an olive-dust suit, white shirt, gray-patterned waistcoat and even a hat as elegant as the erstwhile patron’s. And later the wedding feast, which does not take place at “the white farmhouse,” in less than no time an eternity has passed, they are now living in a fourth-floor apartment in the provincial capital, where she has resumed her studies, but “the endless summer” goes on, the feast in the little room overflowing with light, the mother—assisted by the daughter and the wives of a couple of his friends from the local émigré community—serving a meal so simple that it surpasses even the most select wedding menus at the finest old inns or hotels in the land, and is sublime and unforgettable precisely because neither it nor the usual far-too-long speeches are what you remember afterward, but life itself, he in the unbuttoned white shirt and the waistcoat with its patterned front and jade-green silk back (he has thrown the jacket aside at some point), arms spread across the chair backs behind her and the girl, now his stepdaughter, laid-back in his explosive overpowering laughter, the flashing white teeth and the hair she cut the day before at the round table in the little room, shoulder-length, shiny chestnut brown, he doesn’t give a helping hand at any juncture during the meal, doesn’t even stand up and give the normally obligatory speech to the bride, but that doesn’t matter a bit, the day and age with its equality and gender-role issues is immaterial, his very existence and the love between the two of them is so prodigious that the others are not just, as usual, happy for the bride and groom, but grateful for the opportunity to be present at and share in and be filled with love as it is on that rare occasion when you really believe in it. And “they,” who are they? They are of course the other passengers on “the endless summer” journey, the daughter, the two small brothers, handsome Lars, and the slender and fragile one who is more likely a girl, the lanky Odense lad with the now extremely receded hairline, maybe even the other Portuguese, “o Vikingo,” has traveled hence on account of the celebration, but not Aunt Janne, the maternal grandmother, perhaps, but not the older brother, the lawyer from Aalbæk, this love is of no concern to them, it is beyond their world order, “they” are just the ones they want to be, along with some of the friends he has found in the local émigré community of Portuguese and South Americans, each with his Danish woman, but none like her, nowhere near, the others’ women are the ordinary social education worker types, often rather shapeless, clumsy, but nonetheless cheerful and distinctly Nordic women, fair-haired or freckled and blazing red-heads who go on package vacations to Greece or Spain or are back-packers hitchhiking their way around South America for six months at a time, or are development aid-workers in Africa and return home with a Greek or South American, Middle Eastern or African man, to whom they immediately get married—also at the town hall, but more for procedural reasons because it’s something that primarily has to be done so the man can get a residence permit—and have a child (rarely more than one) and then, in a year or three, divorce, after which the man sticks around in the country for a couple of years and can be seen every day and often from late morning in a café or a community center, where he hangs out with his friends, nearly all of whom are men from his own émigré community, and subsequently sooner or later gives up and returns to the country, the culture, and the language he came from. But these slightly shabby exiles and their tough women with steady employment are just bit-players, extras, the impression of a “people” necessary to make a real queen and a real king; the men laugh loudly with him, sing in Spanish and Portuguese and drink to excess, while the women rather demonstratively exercise restraint with the wine and every so often shake their heads a little and try to make themselves heard so they can continue their conversation about the daily round and, particularly, the men, their difficulty finding work, their lack of discipline, the language they haven’t yet made the effort to learn and, yes, the problems of living together with them, but, as mentioned, these women and their ineffectual men are just the necessary noise it takes in order for the sublime to materialize and ordain its state of emergency, love, that which surpasses all understanding and makes language break out into music that has no meaning, no message, but just is, his explosive laughter and, at his side, her loftily cool and blessing aristocracy.

And a moment later, the honeymoon, the home-taking of the bride, he, the pride and hope of the small provincial Portuguese town, who has been admitted to the distinguished art academy in Lisbon where many of the famous national artists have studied before him, and who all the boys and young men of the town, and especially his brothers, the older brothers too, look up to and admire because not only is he an eccentric artist but he is also a real man who can drink with his own people while effortlessly holding his own with the very small but distinguished company of cultured citizens in the town—and which, in addition to the patron, includes the mayor and a factory owner and the leading local latifundiário with several hundred head of cattle and fifty horses, ten of which are thoroughbreds, accompanied by their wives, of course—this beautiful young man with the elegant, feminine movements and the masculine bearing and a look in his eyes that the young girls of the town and even the little sisters dream and hope might one day catch sight of them, and now he has been away for months and finally returns from a country far up to the north, a kingdom that most of the townspeople have never heard of, and with him he brings his bride, who is not the strikingly gorgeous and gentle and shy and highly distinguished daughter of an old Portuguese family of noble rank that most of the girls had in their wildest fantasies imagined he would most likely bring home from the capital one day, but a complete stranger, a woman who, what’s more, is clearly considerably older than him, and taller!, and what’s more—rumor has it—already has two children, two boys, back home in the country she comes from, and what’s more has been married to another man, one of her own, but who the second she stands there in full view of them is so alarmingly beautiful, so tall, so fair, and not only does she have blue-green eyes, but the most enchantingly long and completely straight hair, sparkling like the finest sand and sort of sweeping across her buttocks, that every form of rumor and skepticism and envy dies away and is transformed in a kind of exhilarated twittering and chattering and enchanted giggling, and when on only her second day she unhesitatingly swings herself up onto one of the latifundiário’s thoroughbred Arabian horses, a high-strung, fiery four-year-old that has hardly been broken-in yet, and rides it without a saddle, just with a cordeo, as if she was a Portuguese man, um machão de verdade, then all the local and traditional rules and gender roles and notions of the ideal wife are suspended, and even the young men who usually hang around the town square on their little motorbikes, and roll cigarettes and light them and have to light them again and rev up and judder two meters forward and raise clouds of yellow dust, are transformed into bashful, giggling, and love-struck boys. For the subsequent days and weeks, the little provincial town is thrown into some kind of euphoria, like when a queen pays her first visit to a minor provincial town, and everyone follows her every move and the reports about her and where she has been today and what she has been doing and where she has been spotted pass from kitchen to kitchen in the destitute and even more destitute streets alike and into the few white villas behind the central square, how she has been spotted very early in the morning mounted on the horse riding down along the river, how after lunch he has taken her to café on the square where usually only the men go, how she has drunk “uma bica” with them standing at the bar like them and one evening had even played billiards and drunk wine with him and one of his brothers in the hall out back used for parties, and how she also mingles with the women in the daytime, helps the young man’s mother and sisters in the kitchen, cleans vegetables and plucks chickens as if she was one of them, and has soon picked up a few words and actually already speaks Portuguese. And one day he takes her along to the prison in the slightly larger neighboring town, where they visit one of his older brothers who has been mixed up in something and possibly killed a man, not intentionally but in a brawl, and the way in which she greets him without any standoffishness and speaks with him and looks him in the eye as if he was a human being, and he is that too, a good-looking man, actually, even though, unlike his younger brother, his teeth are decayed, rotting stumps around a large black gap in the top row where the front four or five have been knocked out, slightly edgy, damaged, a violent, unpredictable, and brittle person constantly twitching his head and glancing to the right where there is nothing, but she just laughs loudly with him and the handsome younger brother who is her husband, and, while they are sitting there talking and laughing, the news spreads down the corridors, from cell to cell and passed on by the prison guards, and it ends with her, again like a queen, accompanied by her handsome youth, having to walk along all the corridors saying hello to the prisoners one by one, shaking their hands through the almost comical bars, which have yet to be replaced by cell doors in this prison deep in the Portuguese provinces, and lastly having to be photographed with the entire throng of prison guards who have en route managed to forget their duty and responsibility and have followed like sheep or little boys behind the two, the queen and her prince consort, in a steadily growing tail along the corridors of the prison. (And there’s also something about the light in Portugal that suits her, liquid golden and at the same time clear, different to the light in Spain and undoubtedly caused by the close proximity of the Atlantic Ocean, and then something gentle and slightly melancholic, which can also be heard in the language, the softness, rounded and somewhat forbearing, a mood in conversations, in laughter and the nights, that also tallies with their love and has the ring of its own termination, the impossible, passion as one long submissive sigh, when the last light is sucked down and carried off on the surface of the water flowing in the riverbed deep down beneath the yellow overhang of rock on which the town was built and upon which—seen from her perspective far below as she rides into the dusk on the back of the almost black-brown Arabian horse—it sits proudly aloft, and where the grubby kids and the washed ones and the washed ones’ mothers and a couple of the sisters and two of the brothers on their patched-up one-hundred-twenty-five-cc motorbikes and some of the slightly older or at least prematurely gone-to-seed men who always sit around on the benches in the little park at the edge of the rock, are crowded together behind the remains of the old fortress wall, looking down at her as she rides alongside the river deep down in the flat and endless lowlands, in silent devotion, as if she is the sunset or is at least pulling it along behind her like a smoldering thunder-red mare into the night.) And then comes the morning when, in bed in the girls’ room—which on account of the visit has been vacated and scrubbed and decorated as a modest but fine bridal chamber with flowers and little bowls with quivering water and candles on the little cement windowsill in front of the also very little window, virtually just a peephole out to the adjacent passageway between the close-set buildings, and the girls, the grandmother, and the youngest brother have moved into the brothers’ room, and the brothers are being put up by various neighbors or with their wives at their parents-in-law—she kisses his brow and in her clear, slightly tremulous, almost strident aristocratic voice says to him that she can’t go on, it is far too overwhelming, all the attention, all these beautiful and fine and warm people, but she doesn’t know how she can do it, she simply has to get a little away from it all with him, him, him. And later that day they take their leave, and the entire little town is in turmoil and distress, the young girls weep and the latifundiário, the mayor, and the patron have—in the case of the first two, for the first time in their lives—gone down into the very humble street in order to say farewell on behalf of the whole town, and she shakes the hands of the fine gentlemen and embraces the women and picks up the youngest little brother and weeps like them and promises that she will soon return, but they will never see her again.

The days and weeks in Lisbon, the clear, higher, harder light out here by the coast, the slightly forsaken haziness of the city, a forgotten region of outermost Europe, the sound of the street-cleaning trucks advancing slowly through the streets behind Praça do Rossio in the last hour before daybreak, like big beetles snorting hoarsely in the dust of the strangely quiet city, which has a far from metropolitan sound, she who, wherever she is, is she who she is, and shows a new side of herself in every place, having drunk uma bica with the local men in the provincial town, standing at the metal countertop in front of black-and-white clad waiters in the café on the square, and along with the mothers, grandmothers, and older girls in the kitchens plucked headless chickens while the ones that were still alive ran around between her legs, here she speaks of aesthetics and art history and Baudrillard’s simulacrum with professors at the art academy and parties far into the night with her youth and his friends at the cafés in Bairro Alto, the professors pour her port in small crystal glasses they keep on a silver tray in the bookcase of their respective offices, and listen to her earnestly and stand up and walk around behind the desk and fetch a recently-published catalogue or a monograph about their work, and place it on the table in front of her and open it reverently, and she turns the pages slowly and looks attentively at each of the pictures, which despite the professors’ exhaustive knowledge of the postmodern condition, of Lyotard, Michel Serres and Merleau-Ponty, are amazingly traditional paintings of Portuguese landscapes and café scenes with an occasional touch of the abstract or the expressionist. The young artist friends, who are part of the new era here and now ten years after the revolution, when money has just started to flow in from the wealthier Europe, and everything is suddenly opening up, and several of them or at least their slightly older colleagues, the ones who have moved on from the academy, have started earning money, good money, are rather more unrestrained, but also not completely free, or suddenly they can hear their own voices and keep catching themselves in perhaps not being (post)modern enough, provincial, they don’t look straight at her, but are nonetheless forever glancing across at her, and when she suddenly quite naturally addresses them, they become instantly sober and ten years younger and straighten up and nod, and the youth can see their self-consciousness and laughs loudly at them and slaps them on the shoulder and flings himself backward in his characteristic jerk that causes the chair to crash and his pageboy hair to flounce, and laughs yet again and yet louder. And all the while they keep an eye on her glass and top it up and turn and shout to the waiter telling him to bring another bottle or a cloth so he can wipe the table in front of her, there, where someone has accidentally ashed, they also find her somewhat mysterious and miraculous—not anything like the Scandinavian interrail-girls in their cotton dresses, their bare dusk-streaked legs and sneakers or espadrilles, or one of the slightly older, single, unduly suntanned or sunburnt women from Germany or Sweden who have occasionally been brought along by people in their circle, and who have hung out with them for some nights or weeks and drunk and danced with them and gone home every morning with the man she had come with, and then one night suddenly with a different one—but at the same time there is an inevitability to it, that one fine day she would be sitting at their table, because also here in the capital city among the young artists, of whom many come from families of artists and intellectuals or are sons and daughters of the upper class of former aristocracy, businesspeople and, not least, generals and colonels from the days of military dictatorship, who have survived the revolution and have continued living as if the twentieth century hadn’t taken place at all yet, even here, among his old friends, he is something very special, a sort of child of nature or uncontrollable genius like Caravaggio, who they, albeit he is one of the youngest, treat with the greatest of respect and from whom they expect the impossible, not just as a painter, but as a mythological figure who was sooner or later bound to return from a long journey with a woman who isn’t even simply a model in Paris or a star from Hollywood, but a noblewoman straight out of one of the candelabra-lit rooms or castle terraces in Barry Lyndon (which at this very time is again showing in the Lisbon cinemas), a completely different era and a completely different world that has never existed.

Next moment they’re back in the Danish provincial capital, and “the endless summer” is to carry on as before, but it’s as if it can’t recognize itself or can’t quite remember how it went about it, as if in their absence time has suddenly started to pass, and the Portuguese light has merely been a glimmer of the impossible or hasn’t been at all. And this is also when the girl and the slender, sensitive, and oh so fine boy part, but say that it is precisely so as not to part, and she goes with the other one, the handsome one with the swaying arms and beautiful open and always empty hands, to America. But that’s a different story, which obviously takes place at the same time as this one, because everything in this coursing tale actually happens at the same time, but it will nonetheless be told at the end, in the cadence (as a final sigh), because it is the one that harbors the definitive, unlike this story of impossible love carrying on across separation and cessation and forever chiming in all of them, continuing long after “the endless summer” is long since over, across death, all this death that is to come.

So here he goes again, the beautiful Portuguese youth, this mythological figure, walking down the street in the Danish provincial capital, alone, defying everything—closed faces, self-contained, miserly Protestantism that no longer has any god other than work, the endless winter, darkness, snow that the moment it kisses the asphalt is changed into slushy, mucky drifts along the curb—wearing his olive-dust-glinting gentleman’s coat, the newly-greased light-brown leather ankle-boots, and the hat, now no longer the “artist’s hat” of “the endless summer” at “the white farmhouse,” but a classic gentleman’s hat as worn by the patron from his hometown, head held high and still occasionally dazzling the passers-by with his smile, his shoulder-length chestnut-brown hair, which she occasionally cuts at the round dining table in the little room on the fourth floor; but as the weeks, months pass, and the winter doesn’t seem to make any progress or look like it will ever come to an end, the slush soaks into the coattails as dull white-rimmed stains on the previously so olive-dust-glinting, the boots can no longer keep the slush out, they too get rims of the salt used to de-ice the streets, the leather starts to crack, the hat loses its supreme patron shape, even the chestnut-glowing hair seems to be kind of splitting, his gait becomes increasingly stooped, with slightly hunched shoulders, no longer seeing Everything like he used to and having energy for Everyone and no longer suddenly exploding with the laughter that could usually cause even the most cautious and self-reliant to stop, against their will, in their tracks or at least turn their head as they left the bank or supermarket and look across at him and happen, against their will, to smile, not that he’s starting to resemble them, he is still an exception, but more as an exotic and delicate, proud and beautiful animal captured and restlessly pacing back and forth or in tight circles on the slushy asphalt in a rundown provincial town’s zoo. You should have seen him! she gushes, the girl’s mother, now his wedded wife, she who had not for an instant throughout the entire honeymoon seen herself, now tells her daughter and the two young boys, the slender and the handsome, about the sight of him as he really is, unfolded to the full, in his own world. What you all see here is just a shadow! she says, thinking of him as he at this very moment, in the midday hour, enters the café on the square in his native Portuguese town, oh, if you only knew! she gushes shrilly, pressing her slim hands with their strong bones against her cheeks, tears brimming in her eyes, Stina! he was radiant! They idolized him, Stina, they did. And then abruptly sad: none of you will ever see him like that, not here, Stina, I don’t know how he can live here, in this country, I can’t do that to him, he belongs down there, but I can’t abandon my children, I can’t! she virtually whispers in the frailest of aristocratic voices, thinking about the two little brothers

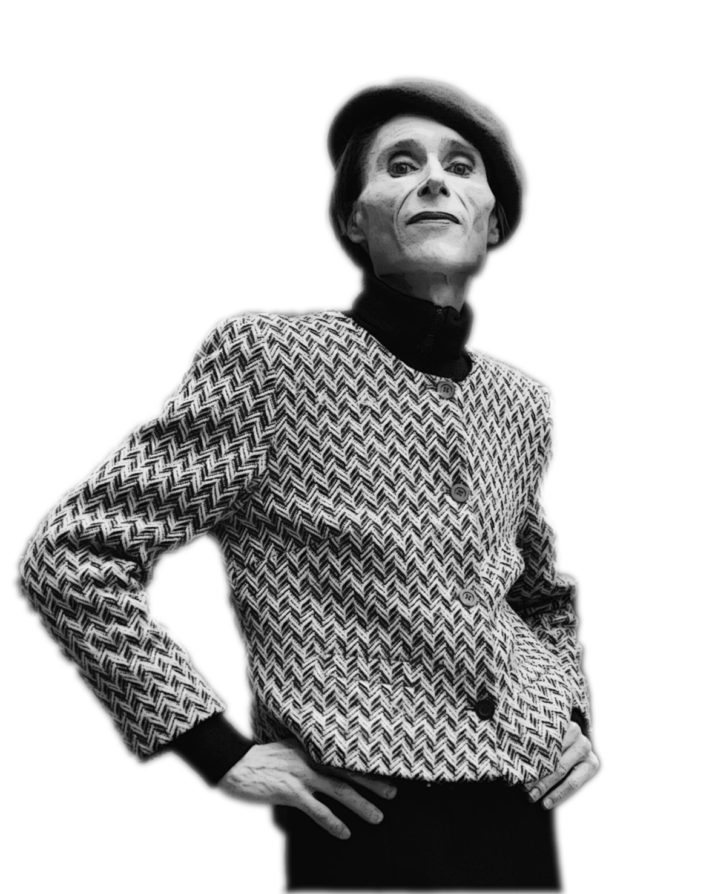

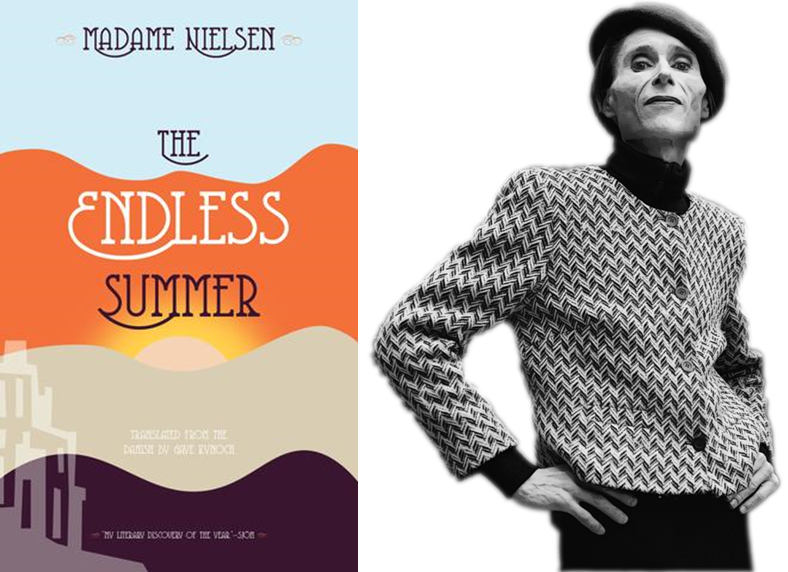

Madame Nielsen is novelist, artist, performer, stage director and world history enactor, composer, chanteuse, and multi-gendered. Madame Nielsen is the author of numerous literary works, including a trilogy―The Suicide Mission, The Sovereign, and Fall of the Great Satan―and most recently, The Endless Summer, the “Bildungsroman” The Invasion, and The Supreme Being. Madame Nielsen is translated into nine languages and has received several literary prizes. The autobiographical novel My Encounters with The Great Authors of our Nation was published in 2013 under her boy’s-name, Claus Beck-Nielsen, and was nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 2014.

Gaye Kynoch is the translator of a book about Karen Blixen (Isak Dinesen) and Lime’s Photograph by Leif Davidsen.

This excerpt from The Endless Summer is published by permission of Open Letter Books. Copyright © 2018 Madame Nielsen. Translation copyright © 2018 Gaye Kynoch.

Published on October 2, 2017.