This is part of our special feature Governing the Migration Crisis.

If creating comes from memory, as the great creator Akira Kurosawa says, then the past, which is preserved in memory, is the very source of our humanity. Without it, we would be nothing but incomplete, semi-conscious things capable of nothing more than functioning. It is therefore impossible to obliterate the past entirely, despite continuous efforts to do so occurring across the globe and across time, whether this be Mao’s Cultural Revolution, the Taliban dynamiting the Bamiyan Buddhas, ISIS blowing up Palmyra, or my maternal great-grandparents smothering their origins as they attempted to assimilate in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century.

As a firm believer in Kurosawa’s words, and in a constant attempt to become a better creator myself, I have dedicated much of my time and efforts to studying the past. This has involved accessing both my immediate memory, and that of my parents and grandparents. Although I have managed to easily put together an effective history of my father’s side—thanks to him immigrating to the US from Italy in the ‘70s, when assimilation was not similarly harsh—until recently, I could confirm only very little about my mother’s side. All I knew for certain was that my great-grandparents had arrived in New York from the Soviet Union—likely Odessa— identifying as Russian. Beyond this were just a few rumors about them and the family they had left behind: one was that my great-grandmother had been a concubine of the Tsar. Another that we had had an uncle living in Harbin, China, which at the time was at the far reaches of the Soviet Union. These rumors were compelling enough to have me prodding insistently at all of my relatives, especially the oldest living—my grandmother—in an attempt to find some truth in them, and to dissolve some of the mystery surrounding this side of the family. Unfortunately, I was only met with dead ends, my grandmother able to offer little in my search.

If creating comes from memory, as the great creator Akira Kurosawa says, then the past, which is preserved in memory, is the very source of our humanity.

This didn’t surprise me. For my great-grandparents, as it was for most immigrants of their generation, the past was a hindrance. It was all about the future. A new life with new appliances and new cars and new names. Nothing old, as the old carried with it the weight of oppressive regimes, poverty, and social immobility. They therefore sought to sever all ties with the Old World, and instead of teaching their native tongue to their children, they spoke to them in accented English, speaking Russian only to one another. Instead of nurturing their children on where they came from, harnessing folktales that had been passed down for generations, they engaged only in the present, embracing even the incorrect spellings and pronunciations of their names, as illustrated below, allowing even the names of some of their siblings and their parents to be forgotten by their children. It was not a question of pride, but one of survival.

This explains why my grandmother hadn’t been of much help. Her only regret at 93 years of age is that she didn’t ask more questions about where she came from. But she was taught to be American, not Russian, and besides the dishes her parents cooked and the music they occasionally listened to, she had little to feed her curiosity; with the stoicism and determination of the hardiest colonists, her parents had succeeded in creating their new lives without giving their children any reason to look back. But pieces of their past persisted, as they always do, and one day they washed up in the drawer of an old cupboard in the form of three postcards they couldn’t bring themselves to destroy. Perhaps they looked longingly at these postcards on rare occasions, and only half-heartedly hid away with the intention that someone would one day find them, as I eventually did. That someone would remember them for who they truly were, and where they came from at a time when it was no longer dangerous to do so; no one wishes to be forgotten, even if we are sometimes forced to forget.

It was not a question of pride, but one of survival.

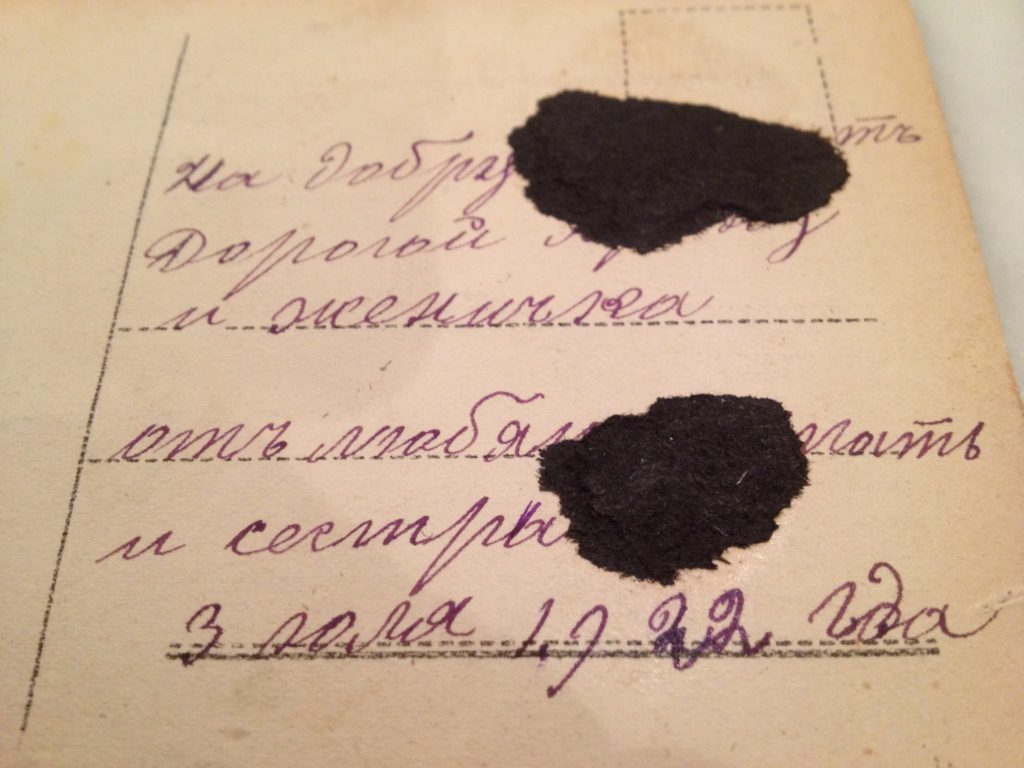

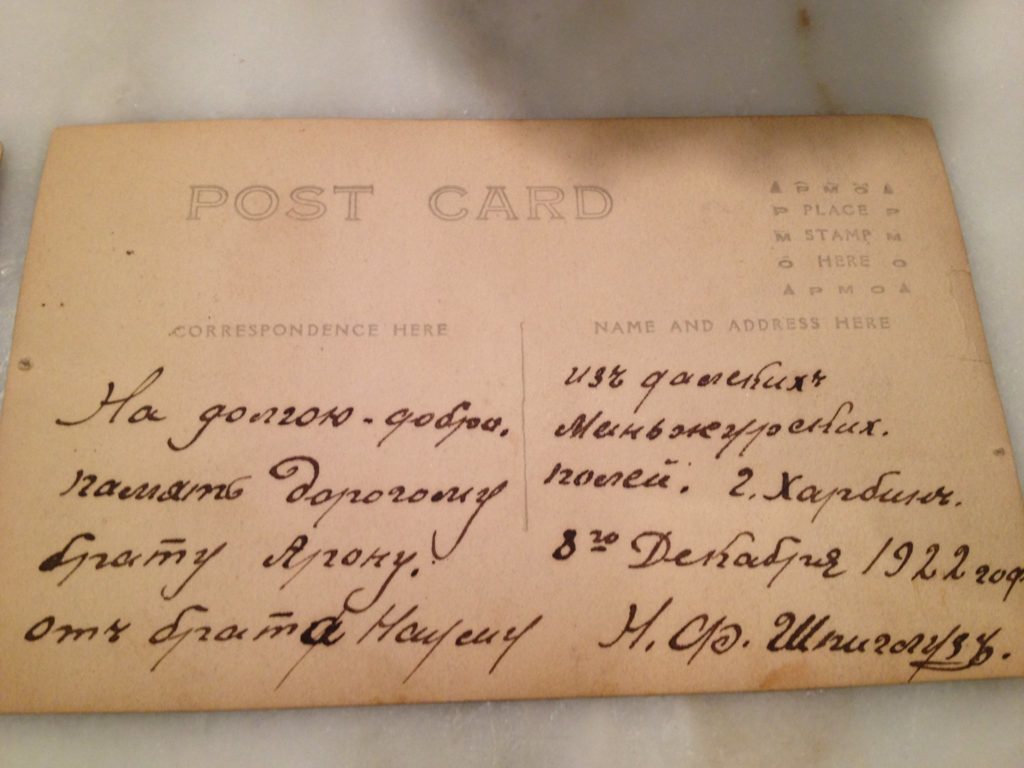

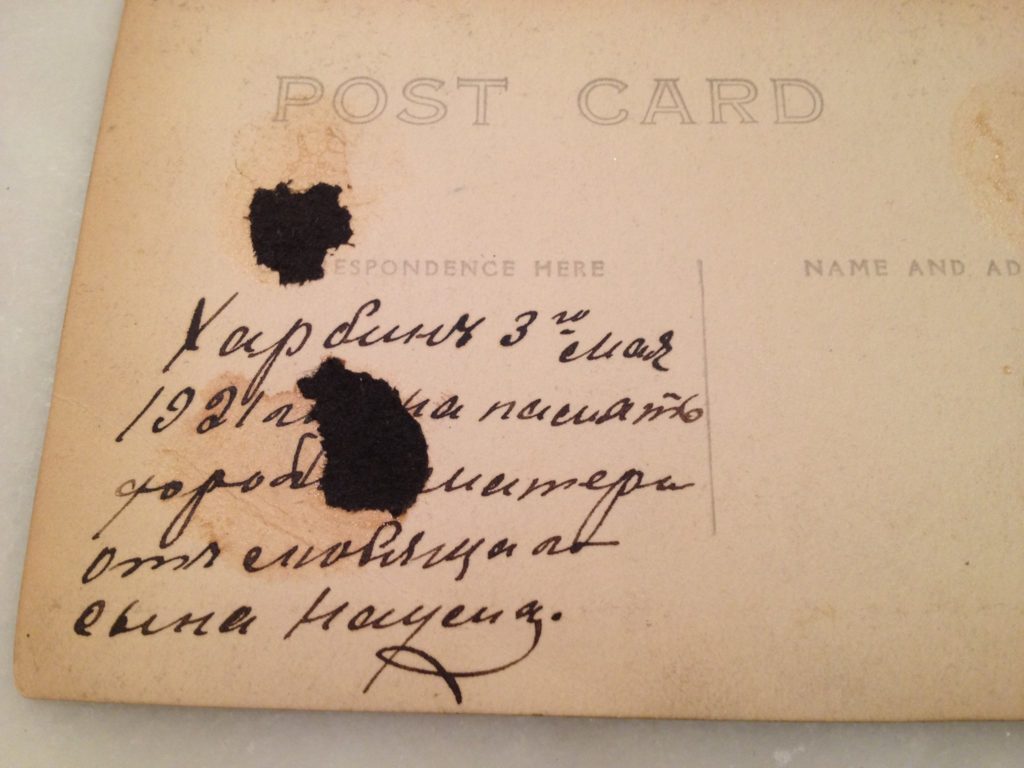

At first, I couldn’t make much sense of the postcards, which all bore handwritten text in Russian and the photographs of a child, two women, and a man whom I didn’t recognize, although he bore a stark resemblance to my cousins. I showed them to my grandmother, but she neither recognized the people in the photographs, nor remembered ever seeing the postcards before. So, I asked a Russian family friend take a look. He was unable to translate any of the words, explaining that they were written in an older version of the language only his own grandmother would be familiar with. But a peer of mine, an archaeologist from Moscow, was not similarly thwarted, and granted me the following translations:

Postcard 1: In good memory to Dear Arran [my great-grandfather] and Eugenia [my great-grandmother] from loving mother and sister, 1922

Postcard 2: In long good memory to dear brother Arran from brother Nahum in far-away Manchurian fields. Town Harbin. 8th December, year 1922. N F Shpigluz [note: the spelling and pronunciation of the family name was changed from Shpigluz (shpee-glooz) to Spiegel (spee-gull)]

Postcard 3: Harbin. 3rd May, 1921. In memory to dear mother from loving son Nahum

A few simple lines immediately confirmed that we had had an uncle in modern-day China, even if, unfortunately, nothing was mentioned about the Tsar. At the same time, as I read these words to my grandmother, they acted like a pneumonic device, stirring awake a string of memories that for decades lay dormant and now spilled unstopped from her trembling lips: her father Arran had had two brothers, she suddenly recalled. One, whose name she couldn’t remember, had been exiled to Siberia as a dissident and was never heard from again. The other, Nahum, whose name she had just learned, was in Harbin on business—more specifically, in the Fabergé egg business; built by the Tsars, Harbin was a prominent trading post between east and west, and became a haven during the October Revolution of 1917, when many Russians fled there. Then, my grandmother began recalling stories not directly related to the postcards, which began to imbue my ancestors with hints of their true identities complete with fragments of their personalities, their love, their longing, their sadness, their guilt, and their shame—all that they were forced to smother as they began their new lives:

She had had a grandmother named Lisa, who had generously supported the local circus troupe that performed nearby her home. When the troupe moved to a different city, they left behind a scraggly dog named Poodlik in thanks, who she took care of ever since; she had had an aunt named Tanya, who her mother Eugenia had described as “wispy and adorable” until returning to Odessa one day, many years after immigrating to the US, clad in a big, black fur coat within which she had sewn all the gifts she was bringing home. There, she was greeted by a frail old lady she could hardly recognized, the ravages of time nearly bringing her to tears. Still, neither time nor distance could destroy the bond between the two sisters, and a correspondence between them continued long after they parted once again, possibly the only connection to the Old World that my great-grandparents wouldn’t sever. Within each letter they pressed a fragrant flower and discussed the wonders of a new life in the New World without mention of its struggles, and eventually, Tanya ventured across the Atlantic as well—she immigrated to Canada shortly after which the last of her letters arrived in New York.

No one wishes to be forgotten, even if we are sometimes forced to forget.

My grandmother always looked forward to receiving Tanya’s letters, which her mother read to her as she inhaled the flower it contained and twisted its stem in her fingers. She remembers that last flower clearly—it was a wildflower with specks of yellow and purple and a scent not unlike that of a lilac. Her recollections didn’t end there, but lasted for a short while in decreasing detail, newly remembered names and nicknames and anecdotes and jokes and broken narratives from lives she never lived fueling our imaginations. And when she remembered nothing more, she stared at me blankly, as if she had just awoken from hypnosis. A clear sense of relief then rushed through her, revealed in her deep, steady breaths, the weight of her one regret lessening—perhaps she had asked enough questions, and was merely met with silence more often than not. A sense of pride revealed itself in her luminous, warm smile for having retained what little her parents risked telling her—no doubt they had wanted to tell her so much more—and for having honored their memory by doing so; for having contributed as tradition dictates for a grandmother, teaching younger generations in the oldest of ways; and for having filled some of the holes that exist within us all that beg to know where we came from to better understand where we are going.

Without the same disinterest that she had shown when encountering her past prior to the postcards’ discovery—which was no doubt the way in which she dealt with her previous inability to remember—my grandmother then listened as I told her about the nature of the writing gracing them. This was proving as fascinating as their content: as my peer had indicated, the one from “mother and sister,” whose names remain unknown, uses perfect spelling and grammar and a neat, educated hand. My grandmother believes this is because one of her aunts, possibly Tanya, was studying to become a doctor. The second two, however, both signed by Nahum, are not as tidy and contain misspellings, bad grammar, and bad handwriting. Furthermore, they seem to have been written by two different people, as the mistakes and the handwriting are inconsistent.

A sense of pride revealed itself in her luminous, warm smile… for having filled some of the holes that exist within us all that beg to know where we came from to better understand where we are going.

The errors point not only to the changing nature of the Russian language at the time, but to poor education and possibly even Russian not being the writers’ first language. They therefore leave us with plenty more questions: was Nahum illiterate, and dictating his letters to only mildly literate friends? Was his first language not Russian, hinting at a different ethnic heritage? Above all else I am left to wonder what he had said when he last saw his brother: my great-grandfather Arran. Did he know that Arran and his wife Eugenia were going to America? Why didn’t he go himself? Perhaps he was already all too familiar with the stresses of living in a land far from home, and wished only to return to his family in Odessa. I also wonder why my great-grandfather clung to these postcards when he was willing to let his brother’s name be forgotten. Perhaps it was his last effort to keep his brother’s memory alive. Perhaps it was guilt: guilt for this willingness, guilt for having left his brother behind when he boarded an unknown vessel at an unknown port and headed west.

My grandmother was unable to illuminate anything on this matter, but she promised to keep asking questions, even if there is no one left alive who can answer them. And afraid to be plagued by the one regret that still plagues her—albeit now to a lesser extent—I will continue to do the same. I will continue to collect memory as I continue to create, and hope that there is not another futile, senseless attempt to destroy the past. This destruction comes largely in a desperate effort to endure, to eliminate what we believe is threatening to undo us. Yet our ability to endure exists with or without destruction, and all that we topple, all that we break, all that we crush will persist regardless in some shape or form—as love, longing, sadness, guilt, or shame. As memory, which is the seed from which our humanity grows and flourishes.

Christopher Impiglia is a writer and art book editor based in New York. He holds an MFA in Fiction from The New School and an MA in Medieval History and Archaeology from the University of St Andrews. He has previously contributed to Issue 2 of EuropeNow, and his words have otherwise appeared or are forthcoming in Kyoto Journal and Columbia Journal, among others.

Published on October 2, 2017.