Translated from the Croatian by Celia Hawkesworth.

This is part of our special feature Governing the Migration Crisis.

On Saturday, November 19, 2002, sixty people incarcerated in a camp for illegal immigrants sew their lips together. Sixty people with their lips sewn reel around the camp, gazing at the sky. Small muddy stray dogs scamper after them, yapping shrilly. The authorities keep assiduously postponing consideration of their applications for leave to remain.

Tereza Acosta is a woman who has decided not to remember. Tereza Acosta does not remember her childhood; it is as though she had not existed until her tenth year. Her amnesia is dense and immobile. Five different Tereza Acostas live in Tereza Acosta. Each has her own voice and facial expressions. None of them remembers conversing with the other Tereza Acostas. Each Tereza denies the existence of the other four. Each Tereza Acosta has her own opinions about marriage, love, work, life in general, quite different from those of the other Tereza Acostas. After many sessions, the doctor decides not to interfere in the lives of the five Terezas, he decides to leave them in their shared oblivion. In which they live harmoniously.

Fausta Fink did not remember her life before the age of fourteen. The doctors gave her antidepressants and she began to remember. She said, Now I’m fine, I’m happy, then she killed herself. She threw herself from the fifteenth floor. In a red kimono. She fell, inflated like a balloon, fluttering. She soared. Then she crashed. In an asylum in the south, or perhaps in the north too, thirty-nine inmates also sew their lips—with surgical thread. To carry out the sewing, the prisoners use a wide, curved needle, and each mouth is sewn with three, at most four, stitches. The patients were protesting against the staff who did not address them. Then, in the asylum, a still greater voicelessness reigned, a vast silence which now wafts like steam, like smoke, from the ceilings and walls of the ruined building in the back of beyond, and climbs in clouds toward the sky; in moonless nights that same voicelessness, that fateful human muteness, apparently insane, is borne back as a breeze; it falls like feathery rain on the opaque windows of our refuge in nowhere-land and, in order to survive, for that is their only air, the patients fill their by now slack, consumptive lungs with that sickly but odorless breeze, that invisible cobweb of silence. The landscape around the madhouse is sealed, petrified, motionless as a drawing. It lies beneath a lava of silence woven of inaudible footsteps that swish softly because they spill out of the asylum in which all slippers are made of felt.

He could do that too. Stop speaking. Stop remembering.

So.

Now he is alone.

In a dilapidated apartment in a small town.

He has talked, written, thought, about this apartment, and about this town, and he isn’t going to do so again. He won’t think. Not about the apartment, where it is cold and dark, neglected, as he himself has become, dark and neglected, and growing steadily colder, not about the town, which he has written off completely, as though it does not exist, as though it has collapsed, sunk into a cataclysmic sepulchre and now he is floating above that abyss (like Fausta Fink in her red kimono), becoming increasingly distant, growing smaller to the point of silence, to disappearance.

He could be anywhere, it does not matter now.

He no longer opens the shutters, maybe occasionally, when some kind of music comes into his head and startles him. When a tiny joy runs through his body, a small pale bolt of lightning that flashes and is swiftly extinguished. Then he opens the windows wide and looks out. From the fourth floor he watches the arrival and departure of trains. He peers into the hangars. Into the garbage bins where rats and cats are up early, he waits for them to dance through the trash and emits a brief ah which stops his breath. With an effort, he raises his eyelids and glances over the shred of sea, swaying there under the low mountain, then the clipboard claps, he withdraws into his cocoon again, and briskly, almost grotesquely, limps down the narrow eleven-meter-long corridor to snuggle like a mole into darkness, into his sepulchral wordlessness and feel once again the way the walls of that virtual tunnel shift, gather, approach one another and then he scampers crazily down that path, up-down hop up-down up-down hop, not to be crushed by its high walls, flattened into a thin line of death like the one on a hospital ECG monitor.

He no longer thinks about anything. He has already thought out everything; his life. In little heaps, small piles, he has laid days, years, births and deaths, loves, the few there were, journeys, many, acquaintances, many, family dramas, his senseless chases and even more senseless small battles, on the whole lost, languages, foreign and local, landscapes, he has tidily classified it all, and tied up that baggage, that now unneeded burden, and arranged it in the corners of the spacious rooms as though yet another great removal awaited him.

A barracks, he says, I’m living in a barracks.

One of these days he’ll ask someone to take it away, this debris, this garbage into which his life has shrunk, he’ll get someone to move those accretions of his botched days out of his sight, so that he and those numerous piles should no longer look at one another as they begin to rot in the corners and give off a nauseating odor, not a frightening odor, but irritating, intrusive, steadily crumbling into dust and interfering with his breath. Take it all, he will say, take it. He has piled up the books, thrown some away, given some as gifts, sifted out the trash. He gives away his clothes as well, and his shoes, at times manically. Too much ballast has accumulated, all kinds of junk. He gives away coats, jackets, suits, sweaters, shirts, oh how many shirts he has, shoes, some never worn.

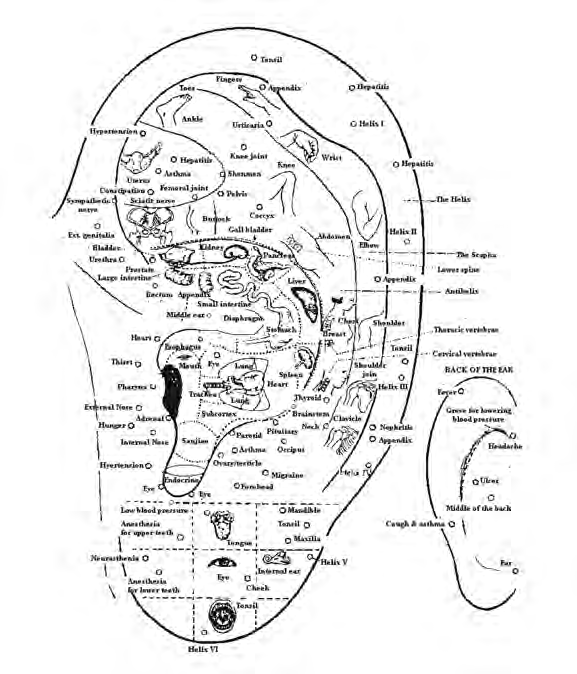

His mother did the same, some thirty years or so earlier, toward the end, as she traveled, leaving behind, handing out pieces of her life, he had not understood it then. When she returned from China from her acupuncture training, with a packet of needles, with enormous rubber ears, acupuncture points marked on them, with a three-foot plastic model of the human body, which could be taken apart and put back together and all the organs removed and examined, charming miniature imitations of organs, heart, lungs, liver, intestines, pancreas, everything, three-dimensional blood vessels, veins and arteries, bones, brain, everything could be dismembered, relocated, rearranged, turned over, put together like a jigsaw, the whole human insides, and the model always stands upright, stuck to a wooden base and impaled on a shiny metal rod, when his mother came back from China to them, to her fam- ily and her psychiatric patients, from China, from some Chinese province, he no longer remembers which, China is a vast country, varied, from that impoverished desert province where, she used to say, the Chinese food was nothing like the European Chinese food eaten in European Chinese restaurants, but meager and tasteless, watery, served (in field hospitals) in tin dishes, as once in the Yugoslav National Army, where she had her hair cut dry, his mother came almost without any luggage, holding a little note torn from a page of newspaper on which the diagnosis ca corpus uteri was written with a ballpoint pen (Chinese). She brought him a small antique Chinese tobacco box made of rosewood which had been gaping empty for a long time over there on his desk where he never went any more, she brought him a framed poem by Lu Hsun, and for his sisters Chinese robes, intensely azure and intensely crimson, with big golden dragons flying on them, and an old fan smelling of sandalwood, all that fitted into one suitcase, a small case in which his mother locked a glimmer of insight, which he later read as a decision and fear.

Now he squeezes that huge rubber ear with its reflex points for the whole body. An ear like a miniature fetus.

On that ear he sees a summary of his organs. All his organs. An overview of his pains. Sometimes he brings a needle, a toothpick or his nail to his ear and pricks his heart, his eye, his back, his brain, and he comes to life. For an instant. He pulsates. When he runs out of money, he finds the point for appetite control and becomes light, he sways as though about to faint.

Ears—a marvelous, ugly organ, repugnant, as is the whole human body, man in general, a grotesque being of discordant shape, with extremities that branch out from a central mass, with thin tentacles that flail around, with tips grafted on them where whitish pinkish formations grow ceaselessly, while at the top of that monstrosity, on a short, soft, mobile stalk rocks a ball-shaped organ with a larger opening at the bottom and two smaller holes in the middle with warm air coming out of them. Toward the top, two small watery balls set in hollows with movable covers roll about silently. In addition, this rounded mobile body is covered with hair that springs out of its top, and on the male also from the front.

There are a lot of ears in literature, there are ears for listening and ears for nonlistening, ears for dropping poison into and ears for cutting off. They say that ears keep growing. Old people have big ears, even those old people whose ears were small in their youth acquire large soft dangling ears with flabby lobes, deaf ears. That is why he was surprised by a recent event when, holding a pink folder against his chest, he got onto a bus, followed by an old gentleman wearing a hat, a man with a deeply lined, furrowed face, who asked him, Are you also going to that building, for the meeting at 4 p.m.? Then the old man who remained standing on the bottom step turned his back on him, the doors were open, and he observed the old man in a black coat from behind. The old man had small ears, unbelievably small, demonic ears.

His ears are all right, his ears are quite respectable, decent ears without hairs. He can hear well, he can hear perfectly well, it would be better if that were not the case. Once, however, the sea had surged in his left ear, occasionally high waves had beaten, roaring, against his frontal bone and dissipated round his temple and nose, words were drawn out into slow unintelligibility with an unbearable echo. They put him in a soundproof room and tested his hearing. The doctor said, Your hearing in your right ear is far above average. You don’t need your left ear at all. But this schizophrenic state of his ears, that noise in his head, that cacophony, only lasted a short time, after a month or two a becalmed sea swayed once again between the walls of his skull. Now he is again surrounded by terrible sounds that come from outside, which hammer on his brain and which he cannot exclude, by the appalling, rending din of this town, unlike any normal city noise.

He has recently read an article about Jewish ears. In it three women were discussing scanned irises and scanned faces in general, and the possibility of implanting chips into people. One of the three women said that she had been dismayed when she was having her photograph taken for a new passport in Vienna and was told, Uncover your ears, we have to see your ears, both ears, they said. That reminded the woman of her mother’s war stories, she said. The other woman said that she was sent back twice by the police when they were getting passports for her grandchildren because her grandchildren’s ears were, first, very small, and second, they were stuck close to their heads. After several attempts they succeeded in getting photographs on which the tips of the children’s ears could be seen, but then there were problems with her grand- children’s eyes, because her grandchildren’s eyes were not open enough to be scanned. When they got to the photographer’s the children would immediately fall asleep. In passport photographs it is forbidden to laugh, even to smile, there was no problem with this second woman’s grandchildren smiling, the second woman explained, because her grandchildren never smiled. In the end, her grandchildren did manage to leave with their parents. From Romania. To where they never returned. Then the first woman talked about her mother saying that in the Nazi era it was not permitted to touch up photographs on Jews’ documents and that the left ear had to be visible, because the Jewish race was allegedly distinguished by the shape of the ear. The Nazis believed that Jews had special ears. In the article, the three women compared their ears but could not discern significant deviations even though one of the three pairs of ears was Jewish. In the end, the Jewish woman found the wartime identity cards of some of her relatives murdered in Treblinka and, indeed, in all the photographs the left ear was clearly visible.

For the time being the police have not analyzed noses although some scientists maintain that there is great biometric potential in scanning noses. The scientists complain that in biometric techniques noses have been unjustifiably neglected. Scanned noses could significantly speed up the recognition of people in the course of processing the entire photograph, which is not the case with standard biometric techniques. A nose does not alter with a change of facial expression, the experts state, while ears do, which is not quite accurate. When people smile, their noses broaden, while there are those whose ears do not stir when they laugh, although there are also those whose ears move up-down, forward-backward, while some people can move their ears even when they are not laughing, by an effort of will. Anyway, the scientific study of forty noses was first carried out in England, then this scientific testing spread through Europe, and now databases (of noses) for future testing are springing up all around.

He has a nice little nose. Regular.

He gathers up souvenirs from around the flat for the trash. He thrusts them into black plastic bags. Decisively, jerkily. Who needs his recollections, which not even he wants to remember, they have fallen into a pit of forgetfulness. And he lets them sink.

People collect idiocies to remember things by because that’s easier for them, no strain—walks, landscapes, smells and touches, no time for that while life flows, or for most people trickles, he realizes that now. People half-wittedly arrange all their life’s paragraphs on shelves and walls and from time to time cast an icy smile at them in passing and say, stay there, wait for me. When the lights begin to fade, people imagine that they will be together again, they and their derelict past squeezed into small dead objects, that they will touch each other again, tell each other mislaid, withered tales. Some hope. Memories die as soon as they are plucked from their surroundings, they burst, lose color, lose suppleness, stiffen like corpses. All that remains are shells with translucent edges. Half-erased brain platelets are a slippery terrain, deceptive. One’s mental archive is locked, it languishes in the dark. The past is rid- dled with holes, souvenirs can’t help here. Everything must be thrown away. Everything. And perhaps everyone as well.

He might keep the little china shoe his mother had given him, a little shoe that had not taken him anywhere. He would also keep the miniature antique grandfather clock, rusty, patinated, a clock with a crooked pendulum that looked as though it had escaped from Wonderland, whose hands moved only when a small coin was inserted into it—a gift from his son Leo. And Elvira, he’ll keep Elvira—he takes her everywhere with him, close to him. There, that’s what he’ll keep.

Daša Drndic is a Croatian novelist, playwright, critic, and author of radio plays and documentaries. Trieste, her first novel to be translated into English, was shortlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 2013.

Celia Hawkesworth has translated The Museum of Unconditional Surrender by Dubravka Ugrešic, Leica Format by Daša Drndic, and Omer-Pasha Latas by the Nobel Prize–winner Ivo Andric.

This excerpt from Belladonna is published by permission of New Directions. Copyright © 2017 Daša Drndic. Translation copyright © 2017 Celia Hawkesworth.

Published on October 2, 2017.