An introduction to our feature The Politics of Health Equity in Europe.

The world-wide projects of colonialism and, in more recent years, global health and healthcare development have positioned the elevated health status of European citizens as the hallmark of effective governance and advanced democracies. Unsurprisingly, health inequalities within European societies have historically garnered much less scholarly attention. While the precise shape and determinants of these inequalities can differ drastically across countries,

It is now well established that Europeans with a lower level of education, lower occupational class, or lower level of income tend to die at younger ages, and have overall worse health.

It is now well established that Europeans with a lower level of education, lower occupational class, or lower level of income tend to die at younger ages, and have overall worse health. This is true even as many of their local contemporaries experience some of the lowest disease rates and longest life expectancies in the world.

Scholarly attention to health inequalities has grown exponentially in the last thirty years.[1] Some of the work in this area has made its way into the mainstream, such as the best-selling book The Spirit Level by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett.[2] The Spirit Level deals with what is termed the “income inequality hypothesis,” and examines the health impacts of income inequality across different high-income countries. Major international institutions have also embraced the importance of addressing the upstream social and political drivers of health inequalities, as exemplified by the 2008 report by the World Health Organization’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health: Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health.[3] This report draws attention to the fact that social inequalities in health result from the conditions in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age.

The essays presented in this special feature address the growing public and political concern over increasing levels of social stratification and reveal the political relevance of health inequalities across Europe. Specifically, we asked health inequality experts to reflect on some of the biggest challenges surrounding health inequalities in different European countries. Their responses highlight the importance of close attention to structural factors in the production of health inequity, signaling that public health is no less political an issue in democratic Europe than it is in the most impoverished and under-developed nations elsewhere.

A major lesson to be taken from these essays is the notion that political institutions are responsible for creating the context both in which social disadvantage emerges and is translated into unequal distributions of health. Jonathan Stillo, for example, reflects on the role of national and international regulations for drug procurement through his fieldwork in Romania, providing an unsettling account of indigent patients’ experiences with drug scarcity in state-subsidized tuberculosis clinics. Other political institutions incriminated by scholars contributing to this feature include welfare state policies, labour markets, and systems of healthcare provision.

Contributors to this special feature also emphasize the difficulties inherent in operationalizing socio-economic status as an indicator of health-related vulnerabilities. Instead, they identify multiple axes of social disadvantage, which extend outside of the dominant measures of socio-economic position. Nadine Reibling, for instance, draws attention to gender issues in the context of health inequalities in Germany; Sund and Eikemo highlight concerns related to individuals’ migration status; and Ted Schrecker sheds compelling light on the importance of regional differences in health. Schrecker also draws attention to particularly vulnerable groups such as lone mothers and children.

Various efforts have been initiated in health inequality research to respond to these complex issues. The adoption of concepts and theoretical frameworks from other fields has proved to be particularly fruitful. Welfare state typologies, for example, have been used to examine the relationship between social protection and health[4][5] whereas more recently, sociological constructs have been employed to develop an “institutional” theory of health inequalities.[6] This theory accounts for how different institutional processes interact to influence distributions of health.

Shifting to the political side of health inequality work, however, contributors to this feature raise two worrying concerns. The first is the nearly universal observation that local health inequalities rank low on European political agendas. The second is the pattern of progressively worsening health determinants across Europe. Nadine Reibling, for instance, notes that Germany lacks a comprehensive political strategy aimed at reducing health inequalities. Ted Schrecker uses the concept of neoliberal epidemics to draw attention to current austerity measures in the UK.[7] He draws a link between these policies and the deterioration of health outcomes, arguing that they have occurred without opposition efforts to highlight their consequences for health equity. Even in Norway, where Sund and Eikemo note that governments once openly acknowledged and sought to address health inequalities, there are signs that the current government is putting such issues aside. Finally, Jonathan Stillo highlights the troubling health outcomes of a nation with limited resources to devote to public health in general, revealing that the absence of political will can have exaggeratedly negative effects in nations where healthcare systems are already organized around an economy of deficit.

Are there any prospects for hope in such a bleak scenario? We propose that further cross-disciplinary exchange might provide some prospect of optimism. As noted above, great strides have been made in health equity literature by drawing on constructs from other fields, such as political science, sociology, and medical anthropology. Others working in these and other related fields may also find that engaging with health equity literature would be beneficial to the advancement of their own disciplines, for example by employing health equity as an outcome variable in analysis of political processes or institutions. Pragmatically, the wider the range of debates brought into engagement with problems of health equity, the greater the attention from political agents on the impacts of progressively rising levels of inequality is likely to be.

Courtney McNamara is a postdoctoral fellow at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Her primary research interests reside at the intersections of trade, social policy, and health. She is currently a project member in the NORFACE project Health inequalities in European welfare states (HiNEWS) and is also Secretary of the Trade and Health Forum within the American Public Health Association.

Jennifer J. Carroll is a medical anthropologist and postdoctoral fellow at Brown University. Her research combines ethnographic and public health methods to increase knowledge of and decrease the harms associated with illicit drug use. She is currently writing a book on the medicalization of opioid addiction in the context of military conflict in Ukraine.

Below are links to the rest of this special round table.

A Tale of Two Britains: Health Disparity in the UK

Ted Schrecker analyzes the regional differences in health in the UK.

Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Neglecting Health Inequalities in Germany

Nadine Reibling sheds light on Germany’s disregard for public health disparity, with a focus on gender inequalities.

Unknown Unknowns: Poverty and Tuberculosis in Romania

Jonathan Stillo examines the role of national and international regulations for drug procurement in Romania, providing a troubling account of impoverished patients seeking treatment in tuberculosis clinics.

Illusions of Paradise? Health Inequalities in Norway

Erik R. Sund and Terje A. Eikemo discuss Norway’s neglect for public health equality, despite the country’s positive reputation.

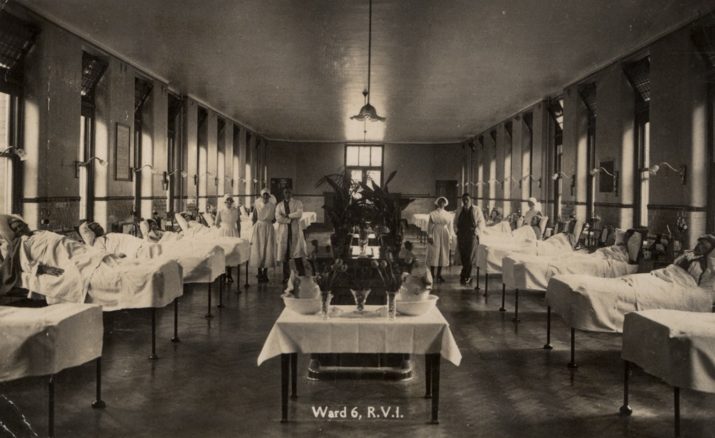

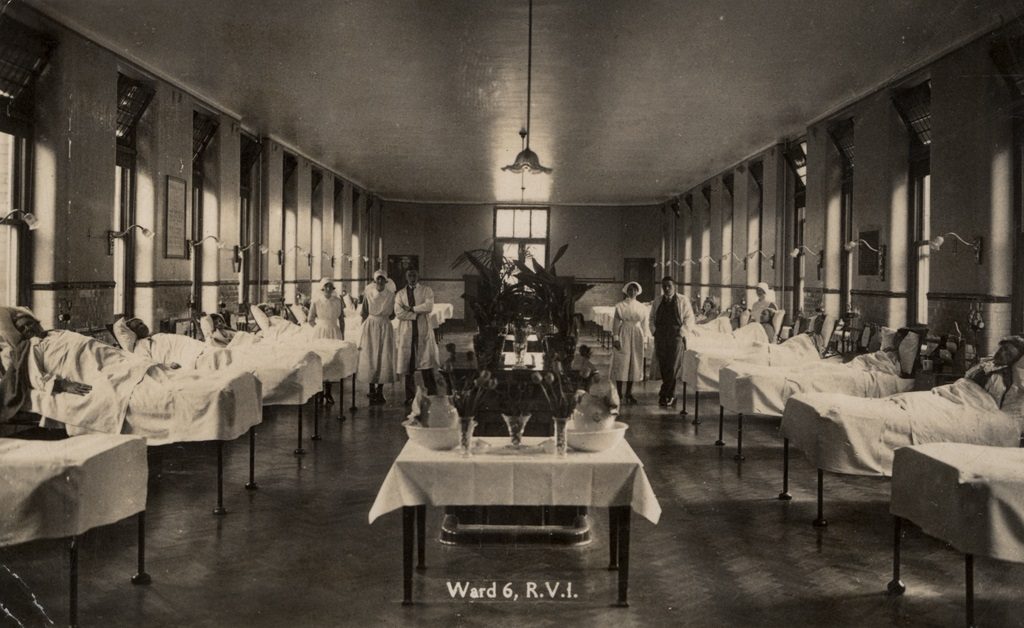

Photo: Ward 6 Royal Victoria Infirmary Newcastle, Newcastle Libraries | Flickr

References:

[1] Bouchard L, Albertini M, Batista R, de Montigny J. Research on health inequalities: A bibliometric analysis (1966–2014). Soc Sci Med. 2015 Sep;141:100–8.

[2] Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. Bloomsbury Publishing; 2010. 350 p.

[3] WHO-World Health Commission. Closing the gap in a generation [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008 [cited 2016 Jun 30].

[4] Beckfield J, Krieger N. Epi + demos + cracy: Linking Political Systems and Priorities to the Magnitude of Health Inequities—Evidence, Gaps, and a Research Agenda. Epidemiol Rev. 2009 Nov 1;31(1):152–77.

[5] Bergqvist K, Yngwe MÅ, Lundberg O. Understanding the role of welfare state characteristics for health and inequalities – an analytical review. BMC Public Health. 2013 Dec 27;13(1):1234.

[6] Beckfield J, Bambra C, Eikemo TA, Huijts T, McNamara C, Wendt C. An institutional theory of welfare state effects on the distribution of population health. Soc Theory Health. 2015 Aug;13(3–4):227–44.

[7] Schrecker T, Bambra C. How Politics Makes Us Sick [Internet]. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2015 [cited 2016 Jun 29].

Published on November 1, 2016.