This article is part of our feature The Politics of Health Equity in Europe.

Germany is one of the richest countries in Europe, and spends a high share of its wealth on welfare provision in general and health care in particular (11 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP), top-five spending country in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development).[1] However, Germany also exhibits substantial inequalities in resources and living conditions that result in social disparities in health. Health inequalities exist in mortality, morbidity, and quality of life.

The life expectancy of a woman with a low income is 8.4 years less than of a woman in the highest income group, while for a man the difference is even greater, at 10.8 years.

[2] People in lower socio-economic groups also report a less favorable general health status and are at higher risk for many chronic health conditions, including depression, heart attack, stroke, diabetes, high blood pressure, osteoporosis, arthritis, and various cancers.[3]

Whether health inequalities in Germany are high or low in comparison to other countries is not easy to evaluate because the answer may differ with respect to the dimension of health, the form of inequality (e.g., education, income, and employment) and the underlying data and methodology. However, several international studies looking at inequalities in self-rated health have found that inequalities in Germany are comparable to or smaller than the European average.[4],[5],[6]

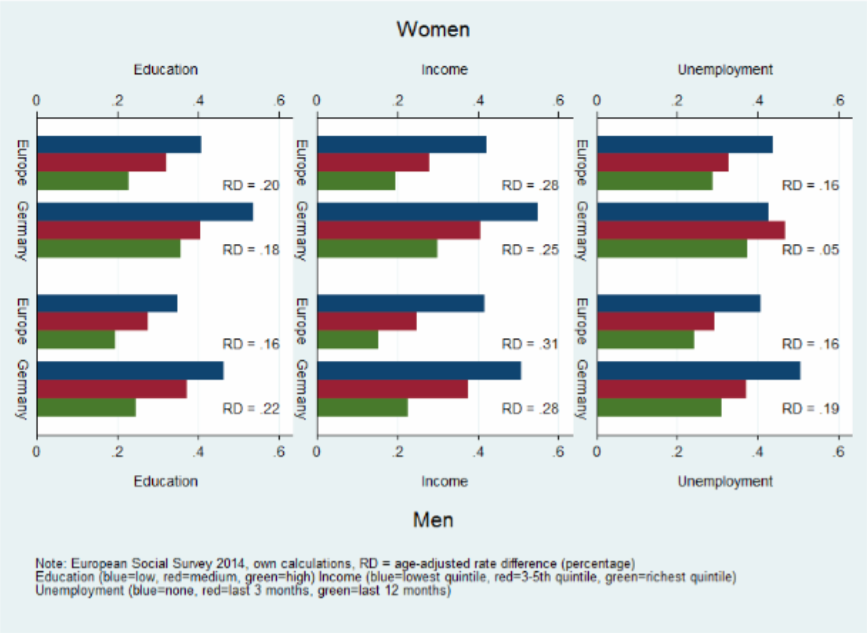

A comparison of data from the 2014 European Social Survey[7] shows that a higher percentage of Germans reports fair, poor, or very poor health than an average of 14 European countries. However, the inequality patterns are fairly similar in Germany and the rest of Europe (see Figure 1). A social gradient exists for education and income for both males and females in Germany as well as in Europe. Also, unemployed people rate their health worse than people who have not experienced unemployment. In Germany, inequalities are greater for men across all forms of inequality, while gender differences vary in the rest of Europe across education (higher inequality among women), income (lower inequality among women), and unemployment (same level of inequality).

Similar to many other European countries, health inequalities have increased over time: Inequalities in self-rated health between income groups have increased between 1994 and 2001 by 82 percent for men and 54 percent for women. Social inequalities in smoking and physical activity have also widened due to a stronger trend towards a healthier lifestyle among the highly educated. Despite the well-documented and rising health inequalities in Germany, tackling the issue has been low on the political agenda.

Despite the well-documented and rising health inequalities in Germany, tackling the issue has been low on the political agenda.

Unlike other rich countries in Europe, such as the United Kingdom, Denmark, or the Netherlands, Germany has no comprehensive political strategy or program that specifically aims to reduce such inequalities. Political attempts to address health inequalities are limited to small health promotion initiatives targeted at socially disadvantaged groups. The national cooperation network “equity in health” links 65 organizations in health promotion and provides information and networking opportunities,[8] but there are no public resources dedicated to the sustainability of the individual initiatives.

Germany also lags in public health regulations that are well known to reduce risk behaviors: For instance, Germany was ranked as the second most liberal country for tobacco control policies in a comparison of 34 European countries[9] and the fifth most liberal country for alcohol control policies in a comparison of 33 countries.[10] Finally, potential implications for health are not an important criterion for decision-making outside of health policies and, even within health policy, cost considerations dominate decision-making. As a result, recent social policy reforms such as the reduced reception period for unemployment benefits and effective reduction of minimum income benefits in 2005 may have contributed to rising health inequalities in Germany.[11]

Figure 1: Health Inequalities in Germany and Europe

Nadine Reibling is a research associate on Sociology of Health and Health Systems at the University of Siegen.

This article is part of the HiNEWS project – Health Inequalities in European Welfare States funded by the NORFACE (New Opportunities for Research Funding Agency Cooperation in Europe) Welfare State Futures programme (grant reference:462-14-110).

Photo: Homeless, Alala Garcia | Flickr

References:

[1] “Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,” OECD Health Data 2013, 2013, <www.oecd.org/health/healthdata>.

[2] Thomas Lampert, “Social Inequality and Health [Soziale Ungleichheit Und Gesundheit],” in Soziologie von Gesundheit Und Krankheit, ed. Klaus Hurrelmann and Matthias Richter (forthcoming, 2016), 121–38.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Olaf von dem Knesebeck, Pablo E. Verde, and Nico Dragano, “Education and Health in 22 European Countries,” Social Science & Medicine 63, no. 5, September 2006,: 1344–51, doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.043.

[5] E van Doorslaer and X Koolman, “Explaining the Differences in Income-Related Health Inequalities across European Countries,” Health Economics 13, no. 7, July 2004, : 609–28, doi:10.1002/hec.918.

[6] T. A. Eikemo et al., “Health Inequalities according to Educational Level in Different Welfare Regimes: A Comparison of 23 European Countries,” Sociology of Health & Illness 30, no. 4, 2008, 565–82.

[7] “European Social Survey | European Social Survey (ESS),” accessed February 12, 2016, <www.europeansocialsurvey.org/>.

[8] “Gesundheitliche-Chancengleichheit: English,” <www.gesundheitliche-chancengleichheit.de/english/> accessed February 12, 2006.

[9] Luk Joossens and Martin Raw, “The Tobacco Control Scale 2013 in Europe,” Brussels: Association of European Cancer Leagues, 2014. <www.europeancancerleagues.org/images/TobaccoControl/TCS_2013_in_Europe_13-03-14_final_1.pdf>.

[10] Thomas Karlsson, Mikaela Lindeman, and Esa Österberg, “Does Alcohol Policy Make Any Difference? Scales and Consumption,” in Alcohol Policy in Europe: Evidence from AMPHORA, ed. Peter Anderson et al., n.d., <www.amphoraproject.net>.

[11] Lars Eric Kroll, Sozialer Wandel, soziale Ungleichheit und Gesundheit: Die Entwicklung sozialer und gesundheitlicher Ungleichheiten in Deutschland zwischen 1984 und 2006 (Springer-Verlag, 2010).

Published on November 1, 2016.