In the early hours of October 7, 2023, militants of the Islamist group Hamas and a few other armed Palestinian organizations struck Israel across the security border surrounding Gaza. Under a barrage of rockets launched from Gaza, a coordinated and carefully planned one-day assault unfolded—the deadliest since Israel’s founding in 1948. Militants attacked Israeli military bases and civilian communities, including people participating in a music festival. They brutally murdered some 850 civilians and 350 soldiers while kidnapping around 250 people, including women and children. Israel was caught flat-footed but responded swiftly. A state of emergency along the Gaza border was declared, and Israel’s Operation Iron Shield got under way. Bombardments and a military incursion into Gaza followed, which, two months later, were responsible for 15,900 Palestinian deaths (40 percent of them children).[1] The conflict became headline news worldwide, resulting in divisive confrontations and antisemitic and anti-Muslim vitriol—including in the United States. It did not take long before the news media proclaimed “the unravelling of Europe’s role in the world” in light of its lack of unity on the issue.[2] Today, such a conclusion is often followed by an analysis as to why European countries have such diverging visions on the region. In this article, we explore some of the reasons behind the varying support for Israel or Palestine among European countries. We analyze and weigh the heterogeneity in recent votes by EU countries and the UK on United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) resolutions that involve Israel and/or Palestine. We close by revisiting the “chaotic” European response to the Israel-Hamas crisis to argue that disunity may have some benefits in the current situation.

2023 UNGA humanitarian truce

In its October 26 emergency session, the UNGA took its first formal action since the violence of October 7. Without unanimity in the security council, the UNGA adopted a nonbinding emergency resolution calling for an “immediate, durable and sustained humanitarian truce” between Israeli forces and Hamas militants in Gaza. It also demanded “continuous, sufficient and unhindered” provision of lifesaving supplies for civilians trapped in Gaza. Of the member states, 120 voted in favor of the resolution, 14 voted against, and 45 abstained.[3] France, Belgium, Ireland, and five other EU members voted in favor, while Hungary, Austria, the Czech Republic, and Croatia voted against. Germany, Poland, and Italy, together with 12 fellow EU members and the UK, abstained. Europe’s divisions were on display for everyone to see. This division was a far cry from the common position articulated on October 15 by all 27 European leaders, which condemned Hamas, affirmed Israel’s right to self-defense (when consistent with international law), and reiterated continued support for the (ambitious) end goal: a two-state solution. The United States and Israel voted against the truce. The Israeli ambassador did not hide his displeasure: “Today is a day that will go down as infamy. We have all witnessed that the UN no longer holds even one ounce of legitimacy or relevance.” He reproached the assembly: “Shame on you.”[4] A few weeks later, the security council would agree to a humanitarian truce.[5]

2022 UNGA votes

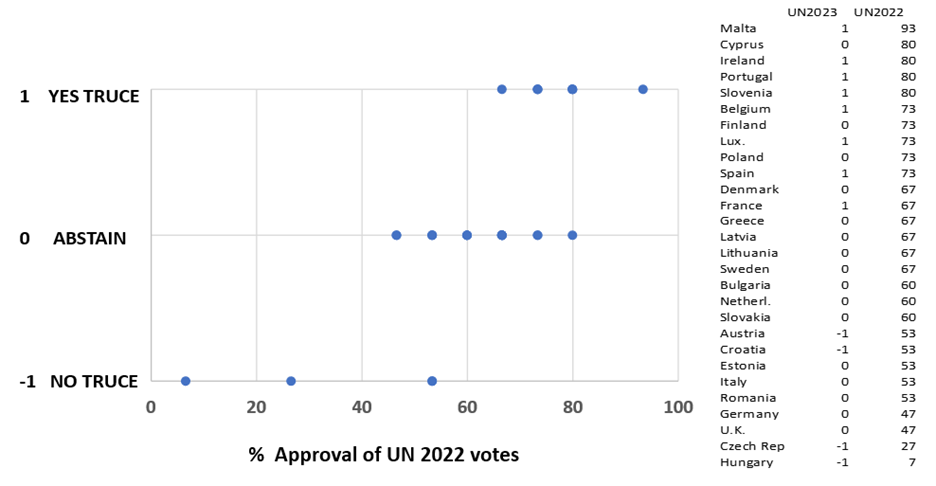

While the press deplored Europe’s leadership, its countries’ diverging votes on the truce were consistent with previous UNGA votes and, as such, should not have been a surprise.[6] In Figure 1, we relate the 2023 truce votes to the 2022 UNGA votes on 15 resolutions involving Israel and/or Palestine. For all EU countries and the UK, we plot the results of the vote on the truce on the vertical axis and the percentage of votes in favor of the 2022 resolutions on the horizontal axis. We score supportive votes with one, abstentions with zero, and votes against with minus one; we sum the 2022 votes and report the total as a percentage of the 15 resolutions. Figure 1 provides a visualization for how support for the truce goes hand in hand with more support for 2022 UNGA resolutions related to Israel and Palestine. As one can see, those voting against the 2023 truce supported only 7 percent to 53 percent of 2022 UNGA resolutions. Those abstaining on the 2023 truce supported 47 percent to 80 percent of 2022 UNGA resolutions. And those favoring the truce were also consistent with their 2022 stances, having voted in favor for 67 percent to 93 percent of 2022 UNGA resolutions.

Before analyzing what potentially drives UNGA votes, we first provide a few observations. The contrast between Europe and the United States is stark. In 2022, the United States voted 14 out of 15 times against UNGA resolutions involving Israel and/or Palestine, only one less time than Israel. In terms of the full range of the analysis, while all European votes are in the positive range (from Hungary’s plus 7 percent to Malta’s plus 93 percent), the United States and Israel scores are decidedly negative (minus 93 percent and minus 100 percent, respectively). With many countries in the UNGA having autocratic regimes and weak democracies, there are legitimate questions about the significance of adopted resolutions, especially for those involving Israel. No country comes even close to Israel in terms of how often that country is mentioned and criticized. Investigations of past records reveal that, from 1990 to 2013, there were 480 UNGA resolutions involving Israel (out of 932 addressing individual countries), and 88 percent of those criticized Israel. The Palestinian statehood question being unresolved, it is perhaps not surprising that most of the criticism toward Israel has revolved around issues of human rights—and nuclear proliferation as the second-most common focus. The sheer volume of (critical) resolutions, however, is hard to fathom. In this 23-year period (1990–2013), Israel was criticized far more often than South Africa (59 resolutions), North Korea (38), Iraq (22), and Iran (22). Resolutions condemning Israel were repeated frequently, and often without mentioning particular violations. For reference, the United States was criticized in 39 resolutions and Palestine in 29.[7]

It may still be worthwhile to investigate how European countries have voted in the UNGA, since their votes do not fit with Becker et al.’s (2014) credible but damning explanation as to why so many resolutions concerning Israel have been adopted with virtual certainty. According to this explanation, weak democracies and autocratic regimes use nonbinding votes to condemn Israel as decoys to deflect attention from their own human rights issues. It is unlikely that stronger democracies such as EU member states and the UK would need to do the same.

European 2022 votes in the UNGA

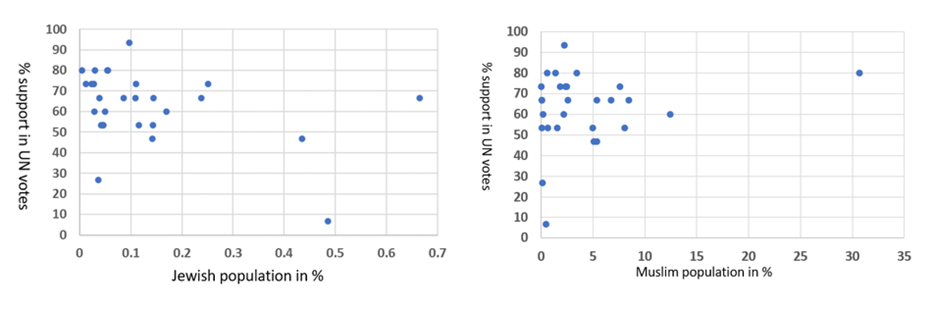

What lies behind the diverging (positive) support for UNGA resolutions that often criticize Israel? In this section, by way of exercise, we investigate a few potential factors, including the size of the Jewish or Muslim population in European countries, the Holocaust, and the importance of trade with Israel. In the aftermath of the Hamas attack, it was not uncommon to hear that the position of individual European countries depended on the size of their Jewish or Arabic/Muslim population.[8] There is no question that concerns about the reaction of Europe’s small and decreasing Jewish community and its much larger and increasing Arabic/Muslim counterpart influence Europe’s response. As Panel A of Figure 2 illustrates, however, there is no obvious way in which the varying attitudes of EU member states and the UK, as revealed by their 2022 votes in the UNGA (shown on the vertical axis), systematically relate to the share of their Jewish or Muslim populations (shown on the horizontal axis). The Jewish population share ranges from tiny (0.02 percent of the total population for Finland) to relatively large (0.7 percent for France) among the stronger European supporters of the UNGA resolutions criticizing Israel. On the other hand, staunch supporters of Israel, such as Hungary and the Czech Republic, which often abstain or vote against UNGA resolutions on Israel, have, respectively, relatively large (0.5 percent) and small (0.1 percent) Jewish communities. Add to this the presence of outliers, and it does not seem like a smaller or larger Jewish population is “the” determining factor for why a European country supports UNGA Israel resolutions more or less. The same is true if one plots a country’s UNGA votes taking into account its Muslim population.

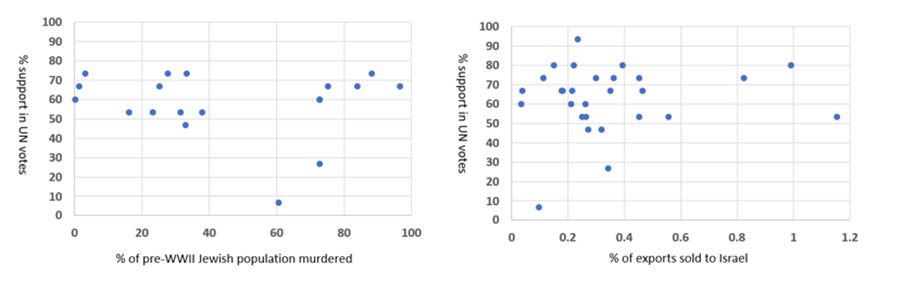

Bringing in more data, as in Figure 3, amplifies the sense that there is not one dominant story to explain the diverging votes of European countries in the UNGA. There is no question that the past, and especially the Holocaust, plays a role in how Europe looks at Israel. Considering the loss of Jewish life in the Holocaust (as a percentage of a country’s pre–World War II Jewish population) versus the UNGA votes (Panel A), it is not clear that this metric explains the varying positions vis-à-vis Israel.[9] Certainly, Hungary’s staunch pro-Israel UNGA votes may relate to the high percentage of its prewar Jewish population that was murdered (60 percent), but this is clearly not true for Poland. Indeed, Poland has approved 73 percent of the UNGA’s resolutions concerning Israel, even when 88 percent of its Jewish population died in the Holocaust. Even Germany has voted almost 50 percent of the time for UNGA resolutions concerning Israel and the Netherlands 60 percent, in spite of a heavy loss of Jewish life in both countries during the Holocaust. In fact, Germany’s voting record in 2022 resembled that of the UK, whose Jewish citizens survived the war relatively unscathed.

Economic relationships by themselves cannot decisively explain countries’ voting behavior either. The European Union is the largest provider of external funding to the Palestinians.[10] At the same time, the EU is Israel’s most important trading partner (absorbing 30 percent of Israeli exports), and it has a preferential trading relationship with Israel, which has included the establishment of a free trade zone. Panel B of Figure 3 plots on the vertical axis the percentage of individual European countries’ exports destined for Israel. Croatia and Slovenia export the most to Israel (1.2 percent and 1 percent of their own exports, respectively). These two countries approve UNGA resolutions (53 percent and 80 percent of the time, respectively) to about the same degree as small exporters such as Slovakia and Sweden. Slovakia, with 0.03 percent of its total exports going to Israel, supports UNGA resolutions 60 percent of the time; Sweden, with 0.04 percent of its total exports going to Israel, supports them 66 percent of the time.

A multiplicity of motivations

There is no question that the past, the size of Muslim and Jewish populations, and other potential explanations that we do not investigate (e.g., left- or right-leaning political leadership, historic ties with Israel, etc.) matter for how European countries consider Israel. It is, however, not clear that they do so in a uniform way. Attitudes toward Israel and reactions to the Israel-Hamas war are likely based on a combination of factors and also influenced by country- or history-specific and ultimately idiosyncratic factors that would have to be analyzed in more detail. Consider, for example, Germany and Ireland. The German government of Olaf Scholz follows Angela Merkel’s 2008 declaration before the Israeli parliament in Jerusalem that made Israel’s security an integral part of the German state’s reason to exist (Staatsräson). In a widely disseminated speech, the current Vice Chancellor, Robert Habeck, repeatedly invoked Germany’s responsibility for the Holocaust in an attempt to disentangle and clarify the country’s stance on both antisemitism and Israel. Burning Israeli flags or praising Hamas’s terror are criminal offenses in Germany, Habeck notes, warning that “Any German citizen who does this will have to answer for such offenses in court. Those who are not German citizens will also risk their residency status. Anyone who does not yet have a residence permit will have provided a reason to be deported.”[11] Yet, despite its existential commitment to Israel’s security and tight restrictions on hate speech, Germany does not consistently vote with Israel and the US in the UNGA, and it abstained in the humanitarian truce vote of October 27, 2023.

Ireland, on the other hand, supported the humanitarian truce and in 2022 was one of the strongest supporters of the UNGA’s resolutions on Israel and Palestine (80 percent of the time). Summarizing its position on Gaza and Israel, the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs asserts on its website that Ireland “was the first EU state to endorse Palestinian statehood in 1980.”[12] Ireland was also the last EU member to open an Israeli embassy (in Dublin). While the Irish government denounced Hamas, manifestations in the country of pro-Palestinian sympathies have been widespread. Ireland’s opposition parties have tried, so far in vain, to have Israel referred to the International Criminal Court. Like Germany, Ireland’s position is often being related to its past. Jane Ohlmeyer, a Trinity College Dublin history professor and the author of Making Empire: Ireland, Imperialism, and the Early Modern World (2023), has noted that Ireland’s own historical experience “has undoubtedly shaped how people from Ireland engage with the Israeli-Palestine conflict.”[13] Interestingly enough, however, this experience had also produced support for the original Jewish quest for statehood.

Diverging opinions as a positive

The Israel-Hamas war is complicated and contentious. From both the Israeli and Palestinian angles, what has happened and what is happening are unacceptable and traumatic. There are no words to describe the murderous brutality and violence, including sexual, of the Hamas attacks that triggered the recent armed conflict. And 15,900 Palestinian deaths, water and electricity shutoffs, bombardments in a confined zone, and multiple relocation orders for Palestinian civilians are hard to stomach. In a conflict so laden by history, including a history of violence and vain attempts at peace, it is difficult to choose a side. What makes it even harder is that those in charge (Benjamin Netanyahu and his extremist government and what is left of Palestinian representation in the West Bank and Gaza) are imperfect negotiators. Contrasting with the hesitant EU, the United States has come out with a strong pro-Israel position, sending weapons and aircraft carriers while assuming it can help (and nudge) Israel toward a solution. So far, this has been a sobering undertaking. It has taken a very long time to get (little) food, fuel, and medical supplies into Gaza, and the hostage exchange has stalled. There is no clarity about the endgame. The United States has, so far, unsuccessfully suggested restraint.

In a conflict such as the Israel-Hamas war, the diverging positions within Europe may have a role to play. These positions reflect the complexity of the issue and the difficulty of “choosing sides.” Unlike the United States, the EU is not a nation-state. It must be underscored that in a polarized and fragmented world, the EU is one of the few functioning international organizations of sovereign nations that are consistently committed to cooperation and compromise and that even accept some degree of supranational oversight (and majority decisions). However, in matters of foreign policy and defense, the EU has the least supranational clout, and decisions on these matters hinge on unanimous, intergovernmental consensus. Cooperation among EU member states happens when the stakes are high enough and when there is common ground. The war in Ukraine has shown that European countries can find unity and act in such circumstances. Before the Hamas attack, there was a consensus about an (ambitious) endgame around which European countries can rally. It revolves around a renewed peace process between Israel and Palestine. The EU has in the past consistently worked toward this process (even when Netanyahu showed little appetite for the EU’s promise of ever-closer cooperation in case a peace process got back on track).[14] This shared position is still reflected in the EU’s declaration of October 15, 2023. There is merit in Europe’s diversity of perspectives (articulated most fundamentally by its official “united in diversity” motto) because consensus-oriented disunity slows down decision-making in high-stakes contexts until a possible endgame comes into focus.

Since the UNGA’s vote on the humanitarian truce in Gaza, a new UNGA emergency resolution was adopted on December 12 that called for an immediate ceasefire. Again, European countries did not vote unanimously. This time, only two countries voted against the resolution (Austria and the Czech Republic), while nine abstained, and 17 voted in favor. This latest vote brings to the fore another aspect of the EU declaration of October 15, 2023: the affirmation of Israel’s right of self-defense as long as it is within the limits of international law. Concerns about the increasing casualties and potential violations of international law are raising the stakes, creating common ground and bringing countries together.

Manuela Achilles is an associate professor in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville (Virginia). She holds a joint appointment in the Departments of German and the Corcoran Department of History and is the director of the European Studies Program and the Center for German Studies. Achilles has published broadly on the political culture of Weimar democracy and is currently completing a book length study of constitutional patriotism in Weimar Germany. Her next book project is on the history and legacies of Hitler and the Holocaust (under contract with Bloomsbury Academic).

Peter Debaere is an economist and the E. Thayer Bigelow Research Chair at the Darden Business School of the University of Virginia. Debaere’s research, on the one hand, focuses on globalization and, on the other hand, on the economics of water. His research has been published in top general interest and field journals and has been funded by the National Science Foundation. Debaere is finishing a (co-authored) manuscript on migration in the first half of the twentieth century.

[1] BBC “How Hamas built a force to attack Israel on 7 October” (bbc.com); “What did Israel know about Hamas’ October 7 attack?”| CNN; “How the Hamas attack on Israel unfolded” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/more-than-15900-palestinians-killed-gaza-since-oct-7-palestinian-health-minister-2023-12-05/

[2] Tocci, N. 2023. “Europe’s chaotic response to the Israel-Hamas war reveals how weak it is.” The Guardian, 30 October. Kerby, J., 2023, “The Israel-Hamas war is exposing Europe’s divisions.” Nov. 11.

[3] UN News, 2023, UN General Assembly adopts Gaza resolution calling for immediate and sustained ”humanitarian truce,” October 26.

[4] Le Monde, October 27. UN General Assembly passes resolution for humanitarian truce in Gaza

[5] Since the UNGA vote on the humanitarian truce, a new UNGA emergency resolution was adopted on December 12, calling for an immediate ceasefire.

[6] UNWatch, 2022, 2022 UNGA resolutions on Israel vs. Rest of the World, Nov. 14. The resolutions deal with, among other matters, the occupation of Syrian Golan, the illegality of settlements in the occupied territories, assistance to Palestinian refugees, operations by the UNRWA, nuclear proliferation, etc.

[7] Becker, R., A. Hillman, N. Potrafke, and Al. Schwemmer, 2014, The preoccupation of the United Nations with Israel: Evidence and Theory, Review of International Organizations, December, 10, p. 413-437. Hillel Neuer, 2023, Antisemitism and Discrimination against Israel at the United Nations, UN Watch, The House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

[8] NPR, on October 30, refers to the size of France’s Jewish and Arab population. In The Guardian, a retired Irish diplomat uses Ireland’s tiny Jewish population (as opposed to the sizeable French and British Jewish communities) to explain its pro-Palestine position. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/20/ireland-palestine-ceasefire-gaza?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

[9] Finding reliable data about pre- and post-war Jewish population is tricky. We use Statista data (with varying dates of prewar populations). Holocaust Encyclopedia, and American Jewish Yearbook data are consistent with our findings.

[10] EU financial assistance to Palestine | Epthinktank | European Parliament. The funding supports building an administrative structure, a physical infrastructure, and humanitarian aid.

[11] Habeck’s speech can be found here: https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-habeck-warns-antisemitism-bears-consequences/a-67281958. Merkel’s speech can be found here: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/service/bulletin/rede-von-bundeskanzlerin-dr-angela-merkel-796170.

[12] For more information about this case study, visit this page: https://www.dfa.ie/our-role-policies/our-work/casestudiesarchive/2014/july/situation-in-gaza-and-israel-irelands-position/#:~:text=Ireland%20has%20directly%20supported%20the,will%20continue%20to%20do%20so.

[13] “It’s part of our psyche: why Ireland sides with ‘underdog’ Palestine”

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/20/ireland-palestine-ceasefire-gaza?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

[14] Karolina Zjelinska, 2023, “Politics prevails- Israel’s trade relations with the European Union,” Centre for Eastern Studies. Politics prevails – Israel’s trade relations with the European Union | OSW Centre for Eastern Studies. Brzozowski, A., 2023, “EU hopes to drive new international peace effort for Israel and Palestine,” Euractiv, Sept. 24.

EU hopes to drive new international peace effort for Israel and Palestine – EURACTIV.com

Photo: Shutterstock | Results of voting by General Assembly on resolution on Israel-Palestinian conflict at UN Headquarters in New York on October 27, 2023.

Published on December 19, 2023.