Translated from the Romanian by Monica Cure.

It’s better that I don’t tell anyone that my mom and dad aren’t home, because all kinds of bad kids will come over, they’ll steal your toys and eat the food off your table and even punch you in the back of the neck, if you put up a fight. And you have to be in good with everyone, to get along with them so that they don’t steal something of yours, or beat you up, so that they have common decency . . . Mom, when you come home, I won’t talk to anyone for three days. The next three days, I’ll smack them all over the nose, those snots who beat up Dan and Marcel. I can’t now, because they’d take revenge on my brothers, but when you come home, I’ll catch them one by one and beat them to a pulp. That’ll teach them not to pick on kids without parents! When you come, I’ll be the proudest girl in the village. I’ll wear that beautiful dress you brought me and twirl in it down the street like a turkey. It’s prettier to twirl like a little peacock, that’s what they call pretty girls, but I don’t know how peacocks twirl.

Our house has become a shelter for kids whose parents beat them. Everyone knows we’re home alone, because we’re almost never visited by an old person, I mean an adult. If only the kids came full, not hungry, because they eat up all our food. They have mothers and fathers, sometimes just mothers, sometimes just fathers, but no one feeds them, they come dying of hunger and scarf down even plain bread as if real black caviar, fine and expensive, were spread on it, the kind we ate once when Mom came back from making long money.

Whenever one comes by who has been beat up especially badly, I call over my brothers to listen. The kid answers all my questions. I ask him in detail on purpose:

— Did your dad punch you right in the head? Twice? So that it made you dizzy . . . Did blood drip from your nose too? A lot. Then did he also give you a kick in the butt? And he was drunk. He reeked and he went to the back of the garden to hurl, meaning to throw up everything in his alcohol-filled guts.

Then I give Marcel a meaningful look (the way Mom used to), Dan is big and already understands.

— Do you see, dummy, what a dad does? And you’re wailing night and day. You want a dad so you can walk around with your head busted up, a bloody nose, hungry and in rags, and hide out at neighbors’ houses? See how all the kids come to us because you’re better off without a dad. We eat all kinds of treats from the store, everything our hearts desire, we’ve got enough money, we have toys and, since we’ve got things to play with, all the kids come over, because they don’t and they want to steal one of ours, or just break one, out of spite.

Marcel, pouty and stubborn, doesn’t say anything. He wants to answer back, but doesn’t know what to say. He can’t think of a single example of a good dad, who stays at home with his kids and takes care of them, loves them, the way he imagines. Everyone who comes to our house complains. Maybe there are good dads too, but their kids stay home, because they like it there. I know this, but I don’t tell Marcel, let ‘im think it’s better without a dad.

— It’s better without a dad, isn’t it, I ask the kids who were beaten and I don’t let it go until they say yes, it’s better.

Last night we got really scared. We heard banging at the door and we all woke up, even Marcel. We armed ourselves to the teeth. Marcel had the small hammer we use for cracking walnuts and he sat down strategically by the bedroom door. Dan had two knives, one for slaughtering pigs, Dad had given it to him when he left, to protect us from enemies, and one from who knows where. I had a hatchet, which I keep under my bed just in case, and we made our way to the door. We convinced Marcel to guard the bedroom. You guard the money under the rug, our treasure, otherwise we won’t have money for food or toys. He knows we can’t live without money and it’s what robbers and crooks are after when they break in, so he agreed to his important mission. Me and Dan went closer to the door, there was no more banging, but we heard strange rustling sounds. If Dan hadn’t been with me, I would’ve fainted from fright. But I’m the oldest and I’m not allowed to faint just like that. We got to the door and didn’t know what to do. Should we open it? What if it’s some crook who wants to kill us? Should we go back to sleep? But how could we fall asleep with someone rustling something at our door at three at night? I put my ear to the door. I heard a dog yelping. But how could a dog have banged on the door so hard? Let’s turn on the light. Outside we could hear something with a really snotty nose sniveling and crying. Let’s ask who it is. Who’s there? No answer, but we could hear the crying more clearly now. Aha, it’s a child crying. I opened the door and saw a tired child, half-asleep, whimpering on our stoop. And dirty, what should we do with him. We didn’t know who he was or why he came. Maybe he’s one of those kids beaten up by their dad, who’s been here before. But how did he get in when the gate’s locked and why didn’t the dog bark at him? Maybe it did bark, but we didn’t hear because we were sleeping. Maybe we forgot to lock the gate . . . Well, it’s a good thing it’s a kid. We suddenly felt sleepy, we were about to fall asleep standing up. Dan went to bed, Marcel was already asleep on the floor, hugging the hammer, the way other kids hug a teddy bear.

I’ve never slept with a teddy bear, they have germs. One time I slept with the cat, when it had hidden under the bed and I thought it was outside. After I had fallen asleep, it got in bed with me. When I wanted to turn over, I felt something heavy on me, I wanted to push it off but then I felt its warm fur, it was sleeping and purring or snoring lightly and I let it stay, I didn’t kick it out. But I didn’t let it sleep with me more than that one time, because Lenuţa told me cats like to sleep on your chest and they smother you to death or their hair can get in your lungs and you’ll die twenty years later.

I put the nameless child to bed on the couch, I covered him with a blanket and he fell asleep immediately.

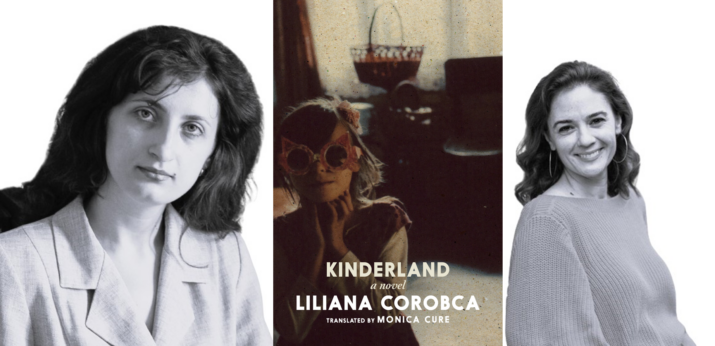

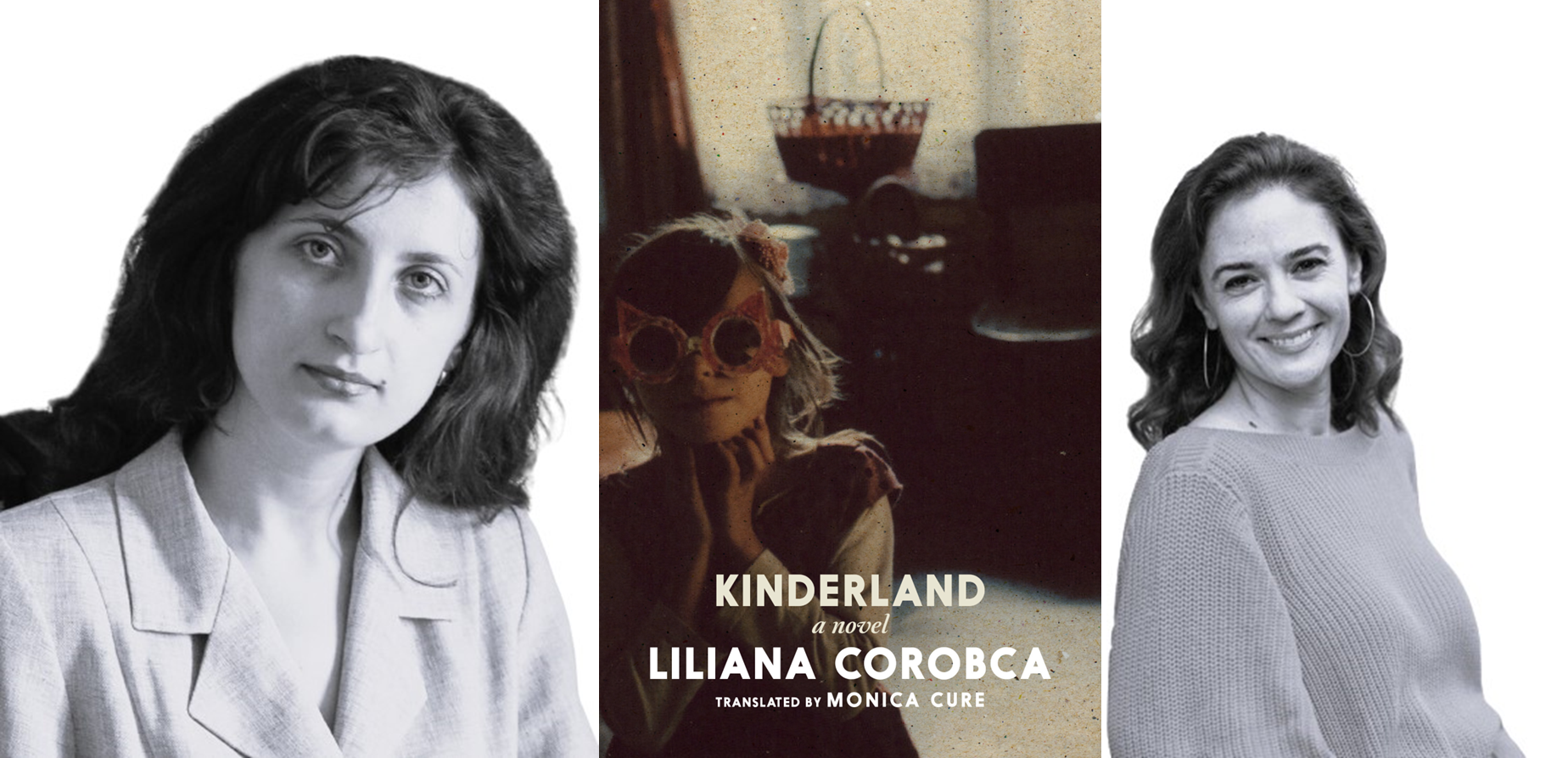

Liliana Corobca is a writer and researcher of communist censorship in Romania. She was born in the Republic of Moldova and is the author of the novel Negrissimo (2003), winner of the “Prometheus” Prize for debut fiction. She is also the author of the novels The Censor’s Notebook (Seven Stories Press, 2022), which won the 2023 Oxford Weidenfeld Translation Prize, A Year in Paradise (2005), Kinderland (2013), and The Old Maids’ Empire (2015). She has received grants and artists’ residencies in Germany, Austria, France, and Poland.

Monica Cure is a Romanian-American writer, translator, and dialogue specialist, as well as a two-time Fulbright grant award winner. Her poetry and translations have been published in journals internationally, and she is the author of the book Picturing the Postcard: A New Media Crisis at the Turn of the Century (University of Minnesota Press). Her translation of The Censor’s Notebook by Liliana Corobca won the 2023 Oxford Weidenfeld Translation Prize. She is currently based in Bucharest.

This excerpt from KINDERLAND: A NOVEL was published by permission of Seven Stories Press and Seven Stories Press UK. Copyright © Liliana Corobca, 2013. English translation copyright © Monica Cure, 2023.

Published on November 21, 2023.