People visiting the bookshop of a contemporary art gallery in any European city might note an unusual abundance of publications. If they time it right, the halls of Tate Modern in London or the Haus der Kulturnen der Welt in Berlin might even be hosting an art book fair, with many small presses and individual artists selling their work from folding tables. If they miss that opportunity, then specialized bookshops in Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam, Bucharest, Copenhagen, Oslo, and other European cities offer a variety of what might be summarized as “poetry, theory, choreography, artist writing and various other text based experiments.” [1] Certainly, these are publications hard to find elsewhere, rarely glimpsed in review pages of literary journals or national newspapers, and even absent from the catalogues of online corporate retailers.

In this essay, I offer a partial map of this field of activity, with the proviso that someone starting from the same bookshops and book fairs could tell a different story or mention other publishers, writers, and artists, with some also conducting “text based experiments” and others positioning themselves closer to fashion, photography, and architecture. Even confining the story within Europe, it would also be possible to pursue a different geography. My focus is English language art-writing publishing by Europe-based visual artists, performers, graphic designers, choreographers, and dramaturgs, but this selection works as a hunch rather than a precise taxonomy. The books I discuss are written in English, which is not the first language of many of their authors; so we face these authors’ conscious decision to use English as a working, common language, which is true also to varying degrees of art book fairs, press websites, and art school teaching. [2] First, I examine some prevalent categories of books in art-writing publishing, both in individual titles and the editorial projects of particular publishers. Then, I outline some of the ways in which this publishing happens, books are distributed and perhaps, hopefully, deservedly, sporadically, and remarkably, sold and read.

Books and editorial projects in the art-writing publishing space

One group of publications in art-writing involves performance. These publications may be a response to the fleeting nature of theatrical performances, with the book medium offering a space to script, document, and critically reflect after the event has taken place. However, in the books I discuss here, these categories have been deepened and transformed, so the books themselves have become a kind of performance, with their own relations to space-time, the body, and the audience.

Since 2005, Amsterdam-based art organization If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution has been “dedicated to exploring the evolution and typology of performance and performativity in contemporary art.” [3] Publications have formed a key part of that activity. Although the formats have diversified, the organization’s Research Projects series began as a series of stapled booklets distinctively designed by Will Holder and presenting an array of text and image projects. Sometimes the research included in these publications has focused on bodies of work by established artists (Desclaux 2014) and at other times on new work developed as part of the Performance-in-Residence program (Moten and Tsang 2018).

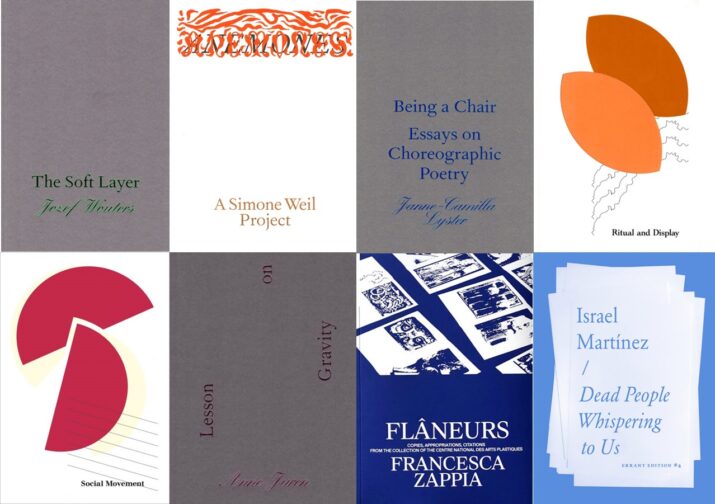

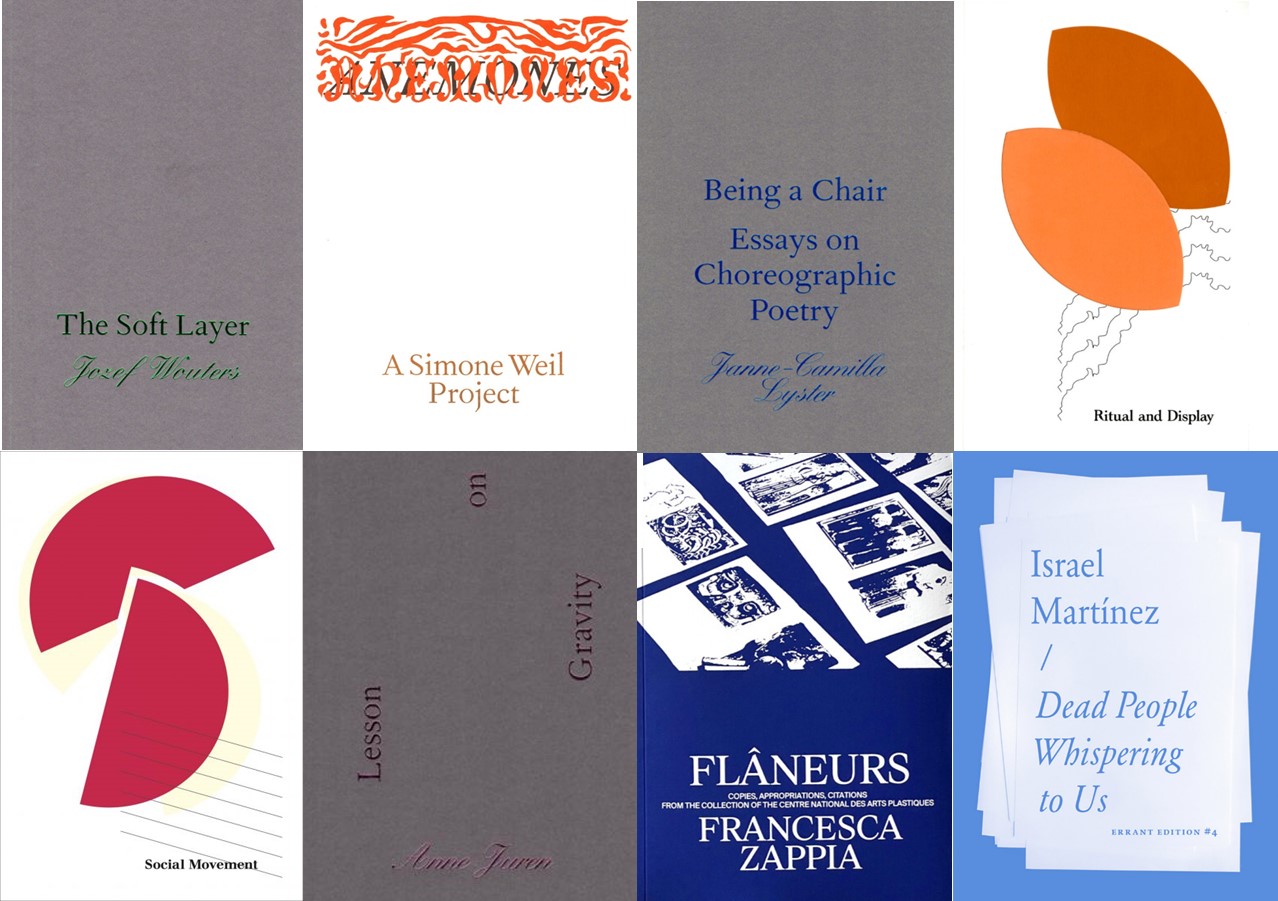

Simultaneously, paperback Readers, including Ritual and Display (Damiani, 2022) and Social Movement: Through the Lens of Performance and Performativity (Fournier 2021), have gathered texts addressed in Reading Groups held for each of the If I Can’t Dance programs. In these books, texts appear as photocopied originals, occasionally with an earlier reader’s underlining and highlighting, contributing to an active sense of continued reading, discussion, and distribution. Moving away from Holder’s standard publication template, recent Research Project publications have “put renewed emphasis on the performativity of the publications,” working with different graphic designers and “reimagining printed matter as a site from which to articulate the spatial and haptic specificity of each project” (Bergholtz and Hoeter 2021, ii). Designed by Rietlanden Women’s Office, Anemones: A Simone Weil Project (Robertson 2021) offers a translation of Simone Weil’s 1943 essay on the Provençal troubadours, a sequence by twelfth-century poet Bernart de Ventadorn, and other essays and supplementary material from both the time of Weil’s essay and Robertson’s 2019-21 research commission. The book demonstrates layers of reading, languages, frames of reference, occasions, and performances that characterize If I Can’t Dance projects more generally.

Rather than a medium-sized, public-funded arts organization, Varamo Press is an outgrowth of the creative practices of its editors, the dancer and choreographer Mette Edvardsen based in Oslo, and Brussels-based dramaturg Jeroen Peeters. Both have used ideas around language, writing, and reading in their performing and devising work, with initial publications at Varamo Press about their various projects (Edvardsen 2019; Peeters 2019). Recently, the press has instigated Gestures, “a series of essays” that fits the broader statement that appears in each publication:

Varamo Press embraces the unexpected and values the arbitrary circumstances in which writing comes into being. Snatching, wording, printing, it gives a paper form to various kinds of literature that have a fleeting life elsewhere. [4]

Books in the Varamo series occupy different points in the performance project of each artist. Anne Juren’s Lesson on Gravity reproduces the script of one of her “fictional choreographic lessons” (Juren 2023, 4). The script can be enacted by readers prepared to shift between their position on the floor and the book at their side, while the book form is ideally suited to the mixture of gesture, idea, fantasy, and reality with which Juren often works [5]. The “performance text” (Wouters 2022, 48) in Jozef Wouters’s The Soft Layer, meanwhile, was devised in response to a particular architecture in Tunis and includes the voice of people telling of their experiences with the Medina and the historic building of Dar Bairam Turki [6]. On a later occasion, that script was performed elsewhere, across the Mediterranean in Palermo. Deliberately excluding photographic and written documentation of these two performances, the book itself presents only transcriptions of the voices. This leaves open to each reader’s imagination the physical and mental architectures the written text inhabits and describes, while also highlighting the incompleteness of the reader’s access to the experiences narrated.

All books in the Gestures series share the small 11 x 16.5 cm format and plain grey card covers, with different colored lettering distinguishing each volume’s titling. Two other titles offer a space of reflection upon creative practice, while still troubling the tenses. Being a Chair: Essays on Choreographic Poetry (Camilla-Lyster 2023) comprises short essays informed by the author’s practice of writing choreographic scores (texts used to devise dance pieces). Writing Dance (Burrows 2023) draws its content from several decades of talks, program notes, and other writings that all “grew out of attempts to put into language things about dance and performance that are slippery or hard to articulate” (Burrows 2023, 5). Four lines from a longer talk are extracted, titled, and written on a single page, as a fragment, which, rather than speaking about Burrows’ own achievements and past practice, has a direct pedagogical value in the present, akin to a choreographer’s concise instruction to a performer in rehearsal.

Ideas for scripts and scores recur widely elsewhere. In the large sheet music-scaled format of Obstacle for Cows (Mühlebach 2023) there are eight sections, each corresponding to one of the artist’s film screenplays. Passages are extracted from dialogues and arranged typographically to reflect the way characters speak, with musical notation added by composer William Aikman. The resultant work is a script but not one that could re-create the original; nor is it an attempt to document the artist’s film in paper form. The constellation of the script’s elements that are provided has a satisfying aesthetic form in itself and insists on some reader response, but nothing is specified. My personal response is a silent reading, my own musical illiteracy rendering Aikman’s stave notation decorative and architectural.

Obstacles for Cows captures the extra energy that comes from moving between artistic disciplines. As some publishers focus on dance and film, others have a background in sound art. The Berlin-based Errant Bodies Press has developed an Errant Edition series [7], within which Dead People Whispering to Us (Martínez 2022) and The Nomadic Listener (Chattopadhyay 2020) both show a sound-based artistic practice finding in writing and the book a container for their authors’ listening-based anthropological fieldwork. The sustainably diverse array of publications from Errant Bodies Press responds to the needs and interests of each project rather than demonstrating the inevitable development of a press towards trade paperbacks and conventional monographs with reproductions of art works accompanied by a critical essay.

Finally, Lydgalleriet is a “non-profit exhibition platform for sound-based and sound-related art in Bergen, Norway” [8], publishing alongside and around its exhibitions program. For example, The Block (and eight other PDF publications) was published by its writer-in-residence (Brzeski 2020-2021), who then curated for the gallery a pamphlet series titled “Vibrational Semantics.” [9] The series includes various forms of scripts and critical reflections that explore “the voice’s ability to shift seamlessly between signification and sonority, from speech sound to noise.” [10] Online PDFs make the work freely available, while hard copy pamphlets utilize page size, fold outs, inserts, and color printing in the production of meaning. By making this work available in print, Lydgalleriet has also entered distribution networks I will explore later in this essay.

The second type of publication I identify is the atlas, an exemplary historical example being Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, compiled in Florence in the 1920s and reconstructed, published, and exhibited in Berlin in 2020 [11]. On wooden panels covered in black Hessian, Warburg pinned photographic reproductions of art works. Each panel demonstrates a particular iconography, often tracing examples of a particular motif from instances in antiquity, onto the Renaissance and, sometimes, into contemporary advertising and art. Within each panel, the size of the images and their placement within the overall constellation indicate accrued significance. For Warburg, this format enabled him to make additions, removals, and re-arrangements as his thinking developed.

Many aspects of the Mnemosyne Atlas (Ohrt and Heil 2020) can be seen in recent publications, with Warburg’s influence either implicit or directly stated. Labyrinth – Four times through the labyrinth (Nicolai and Wenzel 2013) is a catalog of images representing labyrinths in a pocket-sized paperback format. The book stretches from the original Minotaur myth to IKEA floor plans, providing a wide-ranging companion to an art work by Olaf Nicolai, as well as an independent survey of the labyrinth form. In another example, Notre pain quotidien (Maviel 2022) the focus of the atlas is, of course, bread. Here, the large format enables the use of page-spreads that play Warburg-like with thematic arrangements, constellations, and image size and shape. The book might be seen to fall out of this article’s remit, since the only text present is an inserted postcard showing quotes in French by authors such as Francis Ponge and William Morris. But the visual nature and formal language of the atlas medium enables Notre pain quotidien to function, like English language publications, as a common form of discourse and representation within both an art milieu that identifies Warburg’s presence and more widely.

Warburg’s influence is also evident in Francesca Zappia’s Flâneurs: Copies, Appropriations, Citations from the Collection of the Centre national des art plastiques (CNAP). Zappia’s residency at the museum in Paris stemmed from her interest in its nineteenth century collection of copies and casts from famous art works, how that emphasis on reproduction compared to art works from “the postmodern era… governed by the reappropriating of images that have entered collective memory through their massive dissemination within consumer society” (Zappia 2023, 9). The book resulting from her residency is a 572-page gathering of material from antiquity to the present, which sequences images and intersperses them with archival documents and conversations involving the author, CNAP curator Juliette Pollet, and several contemporary artists who also researched the collection. The accumulative effect reconfigures the value and meaning that accrues to ideas of original and copy, demonstrating instead an open attention to the meaning, context, and possibilities of all images and our methods of engagement.

Flâneurs is co-published by the CNAP and Shelter Press, “a record label and publishing platform founded in 2012 by publisher Bartolomé Sanson and artist Félicia Atkinson building up dialogues between contemporary art, poetry and experimental music through printed publications and records.” [12] Flâneurs may seem like an outlier in this list, as it represents a weighty compendium of historical matter in comparison to, say, the delicate drawings, photographs, and minimal texts of The Whisper (Atkinson 2023), which seeks to explore the low register of wind, air, and breath this hushed vocal form supposes. Flâneurs outlines global networks of art history, institutional practices, and social change for the objects it selects, in relation to which other projects of the press may be also viewed. Books like The Whisper suggest that a personal, haptic, and acoustic choreography can inform a researcher’s approach to historical and archival materials.

Organization for publishing

In discussing Flâneurs and other books, it has been necessary to outline aspects of the particular forms of organization out of which art-writing publications emerge and the ways in which content and circumstance combine. Three further examples explore some variant possibilities:

Short Pieces That Move! began in 2018 as a reading and writing group connected to the Master of Fine Art at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam. The group moved out of the institution and went online during the COVID 19 pandemic, expanded its membership, and continues today. In 2022, five long-term participants instigated a new project “on the principles that publishing is possible (we are low-cost, anti-gatekeeping and anti-prestige) and that editing, design, printing and making public all present further occasions for co-learning.” [13] Their first publications were four stapled, card cover, eight-page pamphlets.

First, Guest (Binnerts 2023) is a minimal sequence of individual words and short phrases exploring on the page those spatial and visual arrangements of language that the artist also presented on the walls of galleries. Second, Borderwork (Zdjelar 2023) offers an essay made of prose fragments reflecting upon several projects that developed from the artist’s discovery of archival photographs depicting choreographer Dore Hoyer’s 1946 performance Dances for Käthe Kollwitz. Third, Bowl, Kom, Glow, Gloed, Vase, Vass (Bekkema 2023) offers prose narratives in both English and Dutch that use translation as a dynamic part of the creative process rather than a one-way trip to an “equivalent” English version [14]. A final pamphlet, writing is drawing is writing (Sifostratoudaki 2023) also utilizes the distance of the English-language in attaining a perspective on the self, body, and the senses, while the author (a native Greek speaker) is attuned for how Karamanlidika, a nineteenth-century Turkish dialect, might appear within the pamphlet’s unfolding text. All four publications are guided by a principle of the Short Pieces That Move! reading group: “Our interest is in how an existing piece of writing moves, its directions and turns, and how these moves can be modified or repurposed to initiate new movements in readers and the world.” [15] As Zdjelar writes in the context of the artist Käthe Kollwitz, the intention is to “abandon received narratives” and find ways for the “affective and political force of its sensual and material properties [to] gain urgency” (Zdjelar 2023, 7).

A similar lo-fi aesthetic and politics applies to pamphlets in the Unbidden Tongues series, edited by Isabelle Sully and published by the Kunstverein München, initially using the (now closed) print facilities at Publication Studio Rotterdam. [16] As the colophon tells us, the project “publishes previously produced yet relatively uncirculated work by cultural practitioners busy with questions surrounding civility and civic life – particularly in relation to language and its administration.” [17] The first publication in the series, Introverse Arrangements, by Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt (2020), included selections of the artist’s geometric and poetic works produced on a typewriter while she was employed as an administrator for the German Democratic Republic (when the role ended after unification, so did her creative work). The most recent title in the series, Feelers, by Alexis Hunter (2023), reproduces a selection of the artist’s photographic sequences, for example Secretary Sees the World (1978), whose narrative follows a pair of hands interacting with an office typewriter before holding and crushing a palm-sized toy globe above the keys.

Curiously, the lo-fi, black and white stapled pamphlet could be seen as reproducing an original aesthetic and reproductive technology used in the 1970s and 1980s. While this is somewhat true of Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, Alexis Hunter’s sequences were originally color photographs or hand-colored xeroxes, so their black and white presentation in Unbidden Tongues is part of Sully’s goal “to keep production efforts low, easily reproducible and financially sustainable, so as to contribute as effectively as possible to a wider circulation of the work.” [18] For both Wolf-Rehfeldt (Krischke 2021) and Hunter (Hoare 2019), these publications have contributed to the increased prominence of their work, also enhanced via other exhibition, publication, and archival projects, which the series has always aimed to encourage. Unbidden Tongues as a whole demonstrates an expanded notion of written material. Oral Informants (McCalman 2021) includes a case file of nursing notes from the Melbourne Women’s Hospital, of which the pamphlet’s author—Janet McCalman—wrote a full history.

Finally, Amsterdam-based OUTLINE describes itself as “a publishing platform and floating collective that aims to create interventions within intermediate spaces, and accelerate an exchange by connecting ideas, artefacts, individuals and localities.” [19] OUTLINE projects have included sound works and radio broadcasts, often utilizing track listings and message threads on its Telegram channel. More than the other projects presented here, OUTLINE explores an enmeshment of physical and digital culture, often taking particular, critical positions within this debate, for example through the production of a radio station for the Kunstenfestival Plan B, which was available only to residents of the Belgian village of Bekegem. [20]

Within this context, OUTLINE has produced a number of print publications, in print runs of 150 copies. The Pilcrow series includes pamphlets composed solely of images and text sourced from Wikipedia (Bots 2022; Urbanke 2020; Winkel 2021). More recently, W-Street (plot points and non-fictions) is a journey in which “our protagonist, A., will walk the entirety of one street” (’t Hart 2023, 3). We Do Not Yet Know What ‘Toto – Africa (playing in an empty mall)′ Can Do (Vega 2023) explores the online phenomena of manipulating pop music videos to make them sound as if they are being played in deserted shopping malls. Both titles dialogue enthusiastically with urban studies, psychogeography, hauntology, and feminism, as quotes and ideas from key texts in these disciplines become tested and elaborated in the authors’ investigations. This exploration is aided by the distinctive graphic design of Lulu van Dijck and Tjobo Kho, respectively. In W-Street, for example, the paper is folded so that it can be opened out, interrupting the flow of the main essay to reveal specific notations and illustrations (by Kho) of the author’s journey. Vega’s written text is followed by a sequence of stills from his own film-making, reproduced in the atmospheric monochrome indistinctness attained by risograph printing, a popular printing technology for many art writing publishers. It will be interesting to see how the book figures among the likely diverse media of future projects by the OUTLINE collective.

Forms for distribution and discussion

If these examples suggest some possible forms of organization, how about the distribution of such projects? Alongside websites and artist-run bookshops and project spaces [21], the distinctive form of distribution for many of these presses is the art book fair [22]. Sometimes hosted within larger cultural institutions, stallholders typically range from individual artists to the small presses described in this essay and larger trade publishers. During art book fairs, book launches, readings, talks, and performances are programed elsewhere in the building, further emphasizing the importance of sociality, which arguably often trumps actual book sales.

As the number of book fairs has grown, the format of these fairs itself has been reconsidered. Miss Read: The Berlin Art Book Festival & Fair 2023, held at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt, focused on publishing practices from the East(s)—especially Asia, the Middle East, and the Asian Diaspora—as part of a project for “decolonizing Art Book Fairs.” [23] A support grant was created for artists in the Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) community and for small-scale independent publishers. Even so, the cost of traveling, accommodation, and sometimes table rental remains exclusionary to varying degrees. The Books Are Bridges Art Book Fest in Rotterdam, while attracting some stall holders who also attend larger fairs, suggests a local basis for the book fair, as it is based on collaborations that emanate from more diverse, regional community projects than from Europe-wide and up-sized networks of artists and publishers. [24]

What, finally, is this abundance of decentralized publishing activity creating? There is always a certain mystery to books and to how they might be read, remembered, and applied—or not. There is little critical discourse about the books themselves and nothing equivalent to the reviews that might accompany mainstream novels and non-fiction volumes. But maybe the forms of publishing discussed here enable a particular kind of critical writing. Passing Images: Art in the Post-Digital Age (Rafael 2022) draws on autofiction and memoir to view the works of artists within the digital and physical experiences and communities through which images are now encountered. In 2021, the Berlin-based publisher of Passing Images, Floating Opera Press, launched the Critic’s Essay Series that “gives voice to critics who offer thought-provoking ways in which to subvert or replace normative modes of discussing culture and the world beyond.” [25] Like the Gestures series of Varamo Press, the series has a uniform, text-only design, with variations in cover color. Most recently, Perpetual Slavery (Finlayson 2023) discusses works by African-American artists Ralph Lemon and Cameron Rowland. Finlayson’s essay originally appeared online as an article in the journal Parse (Finlayson 2019). The re-publication of this material as a paperback gives Finlayson a space to clarify critical ideas while suggesting the printed book offers a particular type of engagement and distribution for the essay’s discussions on race, art, politics, and activism.

Last, a theoretical and contextual overview has emerged. The Amsterdam-based publisher Valiz is a frequent participant in the book fairs listed above. It functions as a trade publisher, with its titles widely distributed and available in physical bookshops and online. Its Antennae series “maps the interaction between changes in society and cultural practices” [26] and often does so through a theoretical and critical writing proximal to the kinds of art, writing, and publishing practices described here. Most recently, Sensing Earth: Cultural Quests Across a Heated Globe (Dietachmair et al. 2023) is a primer in which various artistic practices are explored for how they enable a comprehension of and response to environmental issues and futures. In another title from the wider Valiz list (Pol and Vorstermans 2023) the back cover blurb, which also appears in Dutch, asks: “what is the future of books on art, design and architecture, and cultural-critical publications?” Across the 496 pages of Future Book(s): Sharing Ideas on Books and (Art) Publishing, contributors—including various combinations of writer, artist, bookseller, dramaturg, philosopher, translator, and graphic designer—are asked to be “future tellers or future speculators” ( Vorstermans and Pol 2023, 10). Their responses are variously fantastical, humorous, practical, ecological, and technological, among other modes and strategies, some of which return to topics already discussed in this essay, including art book fairs, Aby Warburg, and the choreographic entwinement of humans and books. Here, such bookish practices are considered for how they might be manifesting in five years, twenty years, and far off in 2100.

But my conclusion is elsewhere: in 2010, Edvardsen, one of the founders of Varamo Press, devised the still ongoing performance Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine. Based on a detail of the novel Fahrenheit 451 (Bradbury 1953), the project’s participants each “memorize a book of their choice” and all together “form a library collection consisting of living books.” [27] When chosen by a visitor “the book [the performer] brings its reader to a place or setting in the library, in the cafeteria, or for a walk outside, while reciting its content (and possibly valid interpretations).” If it seems unlikely that participants could memorize a whole book, Edvardsen’s project is about both the possible and the impossible—what she has called “a continuous process of remembering and forgetting.” In Bradbury’s novel, such book-people are outlawed from a society that has found it necessary to ban books. In the context of this essay, Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine is a fable offering insights into different possibilities for writing and publishing.

David Berridge is a writer based in Hastings, UK, researching art writing, fictocriticism, literary and artistic approaches to field work, and relationships with books as a choreographic practice. Essays appear in The Glasgow Review of Books, The Critical Flame, Annulet: A Journal of Poetics, and soanyway. A novella, The Drawer and a Pile of Bricks, is published by Ma Bibliothèque.

[1] This is the “About Us” statement on the website of rile*, ‘a bookshop and project space for publication and performance’ in Brussels, https://www.rile.space/info/about-us (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[2] The Dutch artist Nicoline van Harskamp has developed Englishes MOOC, an online language course whose “About” statement outlines its ‘aim is to emancipate art makers and their audience from having to measure their English along native-like standards in the international realm.’ Week 2 and 4 of the course, for example, focus on Phonetics and Intonation respectively, while Week 3 and Week 5 focus on Postcolonial Englishes and Professional Language, the later specifically focused on the specifics of “Art Jargon,” https://www.englishes-mooc.org (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[3] See https://ificantdance.org/about/ (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[4] This appears as part of a description of the press underneath the biography of the author in the end matter of the publications discussed here. It is also part of a longer ‘About’ statement on the Varamo Press website at http://www.varamopress.org/about.html (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[5] See, for example, the contradictory physical instructions which the lesson often offers participants: the lesson’s opening instruction to ‘lie down and rest on the floor’ being followed, when the page is turned, with “No lying on the floor here” (Juren 2023, 11-12).

[6] See a description of the project’s history at http://www.mennomichieljozef.be/jozef/projecten/layer.html (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[7] Errant Editions is described as a series of “poetics” on the homepage of Errant Bodies Press at https://errantbodies.org (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[8] See https://www.lydgalleriet.no/about-us (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[9] See a full description of Vibrational Semantics as part of Lydgalleriet’s contribution to the project Oscillations, https://oscillations.eu/project/vibrational-semantics/ (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[10] Ibid. This statement also appears on the back cover of the five publications by Lisa Busby, Daniela Cascella, Holly Pester, Cia Rinne and Marie Thams, https://www.lydgalleriet.no/publications-image (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023). For comparative images of print publications see https://goodpress.co.uk/collections/vendors?q=Lydgalleriet (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[11] Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas Mnemosyne was at the Haus der Kulturnen der Welt, Berlin, Sep 4-Nov 30 2020, https://archiv.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2020/aby_warburg/bilderatlas_mnemosyne_start.php (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023). It remains available online as a virtual tour. https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/aby-warburg-bilderatlas-mnemosyne-virtual-exhibition (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[12] See https://shelter-press.com/about/ (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[13] See https://readymag.com/u3104844720/4160594/about/(Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[14] These texts are part of a larger project titled The Sun Becoming an Island – Het Eiland Wordt Een Zon, which the author’s website describes as ‘an ongoing writing project that currently comprises approximately sixty pairs of texts in Dutch and English’, http://www.nielsbekkema.nl/thesunbecominganisland-en (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[15] See https://readymag.com/u3104844720/4160594/about/(Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[16] Founded in 2009 in Portland, Oregon, Publication Studio describes itself as “a publisher of original books distributing through a global network, a printer and binder able to make books one-at-a-time and a social gathering place for those interested in publication or in publishing their own work.” It has opened European studios in Glasgow, London, Paris, and Rotterdam, with London and Rotterdam listed as closed on its website at https://www.publicationstudio.biz/about/ (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[17] This statement appears in slightly variant form in the colophon of the printed pamphlets (the example here is from Hunter 2023), and as part of an extended statement on the editor’s website.

[18] See https://www.isabelle-sully.com/unbidden-tongues (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[19] See https://outline.jetzt/about/ (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[20] Documentation of OUTLINE #2: De Lokale Omroep is on the group’s website at https://outline.jetzt/?outline=outline-2-de-lokale-omroep along with a full catalogue of projects https://outline.jetzt (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[21] One way to gauge the extent of these bookshops is to look at the lists of stockists compiled by individual presses as they develop networks for the distribution of their titles. See, for example, the list of bookshops from Varamo Press https://www.varamopress.org/bookshops.html (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023) and that of the UK-based ‘artist-run publishing project’ FIELDNOTES https://fieldnotes.site/about/ (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023). The Berlin bookshop Motto has developed into a distributor for a number of publishers, and some presses discussed here also use specialist distributors including Les presses du réel (France), Antenne Books (UK), and Idea Books (Netherlands).

[22] A full if non-comprehensive listing of Art Book Fairs since 2017 is maintained by Das Kunstbuch (Association for the Promotion and Dissemination of Artists’ Books), who are themselves organizers of the Vienna Art Book Fair, https://daskunstbuch.at/art-book-fairs-2020/ (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[23] See https://missread.com (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[24] See https://printroom.org/2022/07/02/17-july-books-are-bridges-art-book-fest/(Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[25] See https://www.floatingoperapress.com/about/ (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[26] See https://valiz.nl/en/publications/antennae-series (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

[27] All quotations in this paragraph are from the description of the project at http://www.metteedvardsen.be/projects/thfaitas.html (Accessed 1 Oct. 2023).

References

Atkinson, Félicia. 2023. The Whisper/ Le Chuchotement. Regneville-sur-Mer: Shelter Press.

Bekkema, Niels. 2023. Bowl, Kom/Glow, Gloed/Vase, Vaas. Rotterdam: Short Pieces That Move!

Bergholtz, Frédérique, and Hoeter, Megan, 2021. “Publisher’s note.” In Sara Gianinni. Maquillage as Meditation: Carmelo Bene and the Undead, i-iii. Amsterdam: If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution.

Binnerts, Annabelle. 2023. Guest. Rotterdam: Short Pieces That Move!

Bots, Kim David. 2022. Pilcrow #3: The mental traveller. Amsterdam: OUTLINE.

Bradbury, Ray. 2008 [1953]. Fahrenheit 451. London: HarperVoyager.

Brzeski, Samuel. 2020-2021. The Block. Bergen: Lydgalleriet, https://www.lydgalleriet.no/writer-in-residence.

Burrows, Jonathan. 2022. Writing Dance. Brussels/ Oslo: Varamo Press.

Busby, Lisa. 2022. Belong to Me. 2022. Bergen: Lydgalleriet.

Cascella, Daniela. 2022. Words are my warders but don’t keep an I on me. Bergen: Lydgalleriet.

Chattopadhyay, Budhaditya. 2020. The Nomadic Listener. Berlin: Errant Bodies Press – Errant Edition #1.

Damiani, Giulia, ed.. 2022. Ritual and Display. Amsterdam: If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution.

Desclaux, Vanessa. 2014. Matt Mullican’s Pure Projection Landscapes. Amsterdam: If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution.

Dietachmair, Philipp, and Gielen, Pascal, and Nicolau, Georgia, eds.. 2023. Sensing Earth: Cultural Quests Across a Heated Globe. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Edvardsen, Mette. 2019. Not Not Nothing. Brussels/ Oslo: Varamo Press.

Finlayson, Ciarán. 2019. “Perpetual Slavery: Ralph Lemon, Cameron Rowland and the Critique of Work.” PARSE- Platform For Artistic Research Sweden 9. https://parsejournal.com/article/perpetual-slavery/.

Finlayson, Ciarán. 2023. Perpetual Slavery. Berlin: Floating Opera Press.

Fournier, Anik, ed.. 2021. Social Movement: Through the Lens of Performance and Performativity. Amsterdam: If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution.

Hoare, Nastasha. 2019. Alexis Hunter: Sexual Warfare. London: Goldsmiths Press.

Hunter, Alexis. 2023. Unbidden Tongues #8: Feelers. Munich: Kunstverein München.

Juren, Anne. 2023. Lesson on Gravity. Brussels/ Oslo: Varamo Press.

Krischke, Roland, ed.. 2021. Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt: Gerhard-Altenbourg- Preis 2021. Dresden: Sandstein Verlag.

Lyster, Janne-Camilla. 2023. Being a Chair: Essays on Choreographic Poetry. Brussels/ Oslo: Varamo Press.

Martínez, Israel. 2022. Dead People Whispering to Us (an attempt). Berlin: Errant Bodies Press – Errant Edition #4.

Maviel, Lalie Thébault, 2022. Notre pain quotidien. No place of publication: September Books.

McCalman, Janet. 2021. Unbidden Tongues #4: Oral Informants. Rotterdam: Publication Studio.

Moten, Fred, and Tsang, Wu. 2018. Who Touched Me? Amsterdam: If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution.

Mühlebach, Rhona. 2023. Obstacle for Cows. St.Gallen: Jungle Books.

Nicolai, Olaf, and Wenzel, Jan. 2013. Labyrinth – Four times through the labyrinth. Leipzig: Spector Books.

Ohrt, Roberto, and Heil, Axel. 2020. Aby Warburg Der Bilderatlas Mnemosyne – The Original. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag.

Peeters, Jeroen. 2019. Something Some things Something else. Brussels/ Oslo: Varamo Press.

Peeters, Jeroen. 2022. And then it got legs. Notes on dance dramaturgy. Brussels/ Oslo: Varamo Press.

Pester, Holly. 2022. Five Devours. Bergen: Lydgalleriet.

Pol, Pia, and Vorstermans, Astrid, eds. 2023. Future Book(s): Sharing Ideas on Books and (Art) Publishing. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Rafael, Marie-France. 2022. Passing Images: Art in the Post-Digital Age. Berlin: Floating Opera Press.

Rinne, Cia. 2022. Dear Ear. Bergen: Lydgalleriet.

Robertson, Lisa. 2021. Anemones: A Simone Weil Project. Amsterdam: If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution.

Sifostratoudaki, Vasiliki. writing is drawing is writing. Rotterdam: Short Pieces That Move!

’t Hart, Jan-Pieter. 2023. W-Street (plot points and non-fictions). Amsterdam: OUTLINE.

Thams, Marie. 2022. A Tone or Two. Bergen: Lydgalleriet.

Urbanke, Annosh. 2020. Pilcrow #1: Backpacking. Amsterdam: OUTLINE.

Vega, Mateo. 2023. We Do Not Yet Know What “Toto – Africa (playing in an empty mall)” Can Do. Amsterdam: OUTLINE.

Vorstermans, Astrid and Pol, Pia, 2023. “Het nu van de toekomst/ The Now of the Future (Inleiding)/ (Introduction)” In Pol, Pia, and Vorstermans, Astrid, eds. Future Book(s): Sharing Ideas on Books and (Art) Publishing, 8-10. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Winkel, Romy Day. 2021. Pilcrow #2: Bundle theory. Amsterdam: OUTLINE.

Wolf-Rehfeldt, Ruth. 2020. Unbidden Tongues #1: Introverse Arrangements.. Rotterdam: Publication Studio.

Wouters, Jozef. 2022. The Soft Layer. Brussels/ Oslo: Varamo Press.

Zappia, Francesca. 2022. Flâneurs: Copies, Appropriations, Citations from the Collection of the Centre national des art plastiques. Regneville-sur-Mer: Shelter Press, and Paris: Centre national des art plastiques.

Zdjelar, Katarina. 2023. Borderwork. Rotterdam: Short Pieces That Move!

Published on November 21, 2023.