This is part of our campus spotlight on Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, with Columbia University.

Archaeology became institutionalized in French universities significantly later than in other European countries, especially Germany. The first chair of archaeology was established at the Sorbonne—and roughly at the same time at the University of Bordeaux—in 1876. The first incumbent was Georges Perrot who, despite the prestige of the position, quickly preferred to be entrusted as director of the École normale supérieure, from which he originated—and which still ranks higher in France than any university (on the grandes écoles in France, see Bourdieu 1996). Maxime Collignon, who previously had held the chair in Bordeaux, was then appointed as deputy professor in 1883 to replace him in Paris and became the formal holder of the Sorbonne chair of archaeology in 1900 until his death in 1917 (Bruneau 1992; Therrien 1998, 243–249). Collignon would have a most decisive influence on the creation of an effective chair of archaeology at the Sorbonne, not only in terms of teaching and scientific production, but also in terms of facilities and available instruments. Faced with the absence of a French tradition and despite the existence of the École française d’Athènes since 1846—the French advanced school for archaeology in Greece, of which he was a member—it was to Germany that Collignon turned to define a model for teaching archaeology in France. He undertook a mission across German universities in the early 1880s and on his return wrote a report for the Minister of Public Instruction, which he summarized in a paper, “The teaching of classical archaeology and the cast collections in German universities” (Collignon 1882). Three German particularities had caught his attention: (a) courses were based on collections of figurative monuments, real or reproduced; (b) in addition to the lectio magistralis, the students were invited to actively engage in the field through practical work on objects to be described and analyzed; and (c) a chair of archaeology had to be provided with a collection of plaster casts and antiquities. For Collignon, these characteristics logically had to be implemented at the Sorbonne. His subsequent efforts were gradually supported by Henry Lemonnier, who soon held the first chair of art history created at the University of Paris in 1893.

The time coincided with the construction of the new Sorbonne, built by architect Henri-Paul Nénot between 1884 and 1901. While Perrot had complained about his work environment in the old premises dating back to the time of Richelieu, Collignon was largely responsible for setting up an archaeology department in the new Sorbonne buildings, including a cast museum, a library, and what he called an “Archaeology Room” (fig. 1), similar to the facilities he had seen in German universities. In a paper explaining how the teaching of archaeology was organized at the Sorbonne, Collignon noted that

Real progress was made when it was possible to outfit an ‘Archaeology Room’ at the Sorbonne, in the wing reserved for special institutes. This room, which is open to students, contains what can be called the apparatus of the course, books with plates, photographs and a library which is still too small. Students can also find a collection of small casts and a modest series of original objects (Collignon 1899, 196, translation by author).

As Nénot’s Sorbonne had barely been completed, Collignon already complained about the cramped conditions within the new building, waiting for the day when the university would “find, outside the too narrow walls of the Sorbonne, a site large enough to house the collection” and calling for a generous donor to imitate the American philanthropists (Collignon 1899, 197–198). The project of an Institute of Art and Archaeology was mentioned as early as 1913 by the Rector Louis Liard, but the war would interrupt the project for a few years. In 1923, the Marquise Arconati-Visconti, a major patron of the University of Paris, bequeathed 3 million francs to the university in her will for the construction of such a structure. A plot of land next to the Luxembourg Gardens was donated by the State, and architect Paul Bigot won the competition for the construction of the new building. A former resident of the Académie de France in Rome, Paul Bigot did not build much, but his work is no less remarkable. For example, he was acclaimed for his monumental plaster model of the ancient city of Rome, which would find a place within the new institute in Paris. From 1924 to 1931 he built an astonishingly audacious building made of steel and concrete behind an envelope of red bricks mirroring Venetian architecture (Texier 2005). The new Institut d’art et d’archéologie arose on the corner of avenue de l’Observatoire and rue Michelet, originally intended to house three professors and a few hundred students (fig. 2).

When the building opened in 1932, the 400 or so students who were to attend courses in archaeology and art history were immersed in an atmosphere of erudition, which included not only the classrooms, but also, and even more so, a cast museum and exhibition galleries, various archaeological collections, a photo archive containing tens of thousands of prints and glass plates, and several research libraries, including the Jacques Doucet’s art and archaeology library. This library was then (and still is today) the largest in France in the field, although it is now housed in the former locale of the Bilbiothèque nationale. These remarkable study conditions were accompanied by a cultural program—concerts were given every week in the large auditorium in the basement—and the institution came to enjoy an international influence. The course offering was widely distributed, while summer schools enabled professors based in Paris to attract American students and disseminate their knowledge across the Atlantic. In its conception, the Institut d’art et d’archéologie was not only a facility for teaching; according to the principles that led to its construction, it was to be a laboratory, a place for “science in the making.”

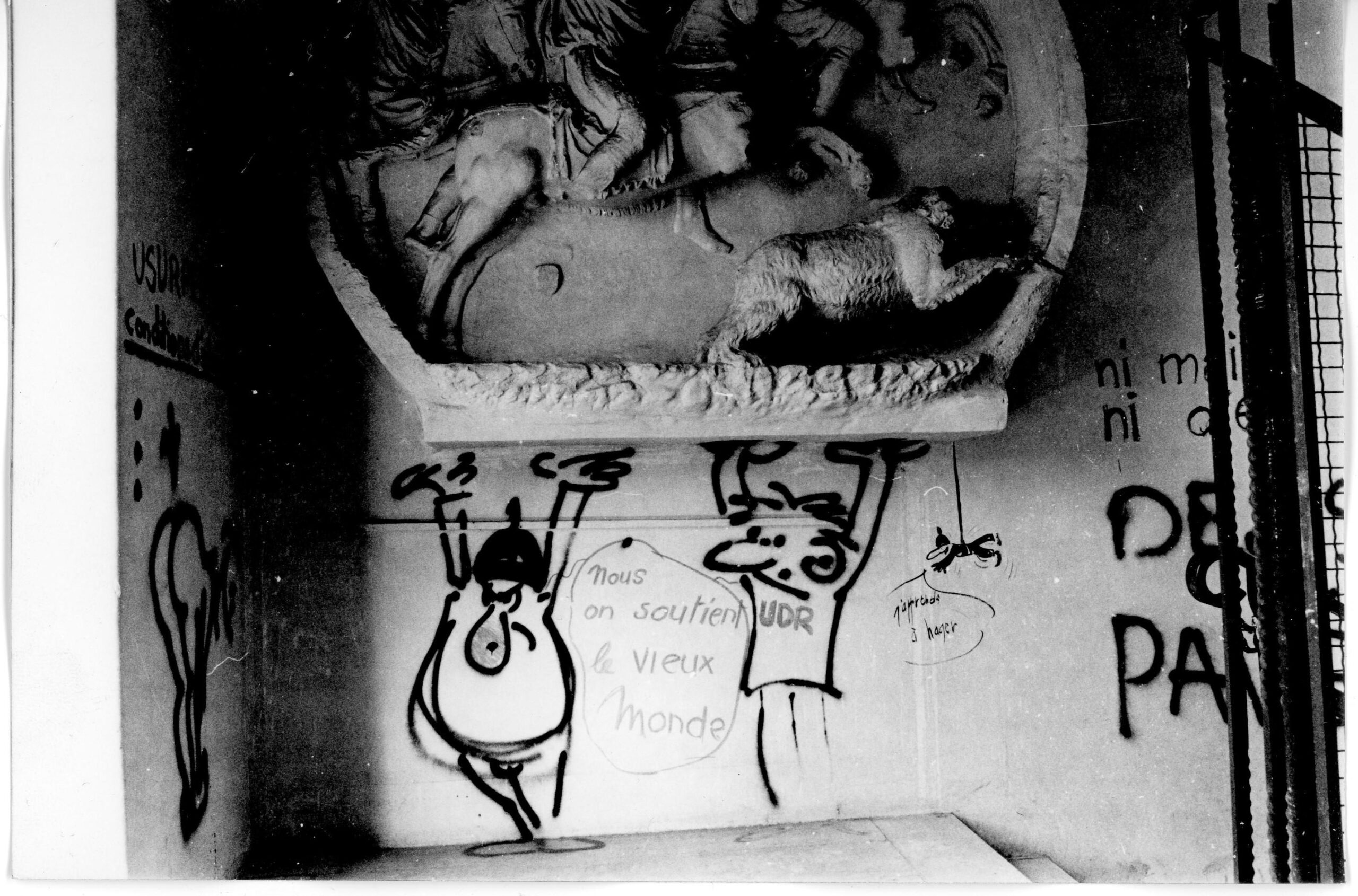

Despite being closed to the public during WW2, the Institut d’art et d’archéologie suffered some damage. From 1941 onwards, the building was practically abandoned, although various urgent interventions were carried out, notably on the roof. In the post-war period, teaching and research activities resumed according to unchanged principles, but the period was also marked with an overall lack of funding for the building’s maintenance and an ever-growing population of students. Then came the events of May 1968. Amidst the student and social insurrection, the building and its collections suffered enormously: many plaster casts were vandalized or destroyed, while the walls of the institute were stained with graffiti when the students involved in the movement chose the building as a meeting place for its action committees, as shown in photographs taken by Jo Schnapp during the second half of May (fig. 3). Virtually besieged by the Compagnies républicaines de sécurité (CRS, a section of the French National Police responsible for crowd and riot control), the stained staircase and upper floor of the building, as if echoing the insurrectionary charge of the slogans deployed in the streets, showed another facet of the May 68 movement (see Lewino 2018, with Jo Schnapp’s photos). Indeed, beyond the punctual material degradations, the splitting of the University of Paris into thirteen universities marked the real turning point in the teaching and scientific project of the Institut d’art et d’archéologie.

The decree of March 21, 1970, establishing the universities of the Academy of Paris, distinguished between Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne and Paris IV Sorbonne. Instructors had to choose between the two new institutions, which became independent from one another. De facto, the Institut d’art et d’archéologie of the University of Paris, whose architectural reality coincided until then with a research and teaching department dependent on the Sorbonne, ceased to exist. Two new university departments of art history and archaeology were created on the ashes of the previous institute, one dependent on Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and the other on Paris IV Sorbonne. Moreover, in the early 1970s, the building itself underwent profound—and often unfortunate—modifications to cope with the student demographic pressure. The cast and exhibition galleries were dismantled (fig. 4). The need for space and the divorce between the two universities explain why approximately 330 plaster casts were sent to the Petite Écurie at Versailles in 1973, where they eventually became part of a plaster cast gallery administrated by the Louvre Museum (Martinez 2009). The dismantlement or the splitting of the teaching collections also meant that the educational project that had been achieved since the creation of the institute was ruined. From then on, each university carried out its own policy, generally with no concern for their common heritage. The listing of the building in the Inventaire supplémentaire des Monuments historiques in 1994 did not change the situation much, except that it further froze the building into the past; it was transformed into heritage, and it also increasingly became disconnected from pedagogical evolutions and institutional realities. For decades to come, the cohabitation between the two universities would be tense, especially regarding the management of the building, which quickly came to be considered nothing more than a physical space for teaching, while archaeological collections that previously made-up teaching were forgotten.

Things have however progressively changed, for the better. As the archaeological collections are now rediscovered and studied, an architectural project jointly elaborated by both universities resulted in the awarding by the state in 2021 of a generous grant of 8 million euros for a major renovation project—to be supplemented by an equivalent figure contributed equally by the two universities. The completion of the renovation work is scheduled for the end of 2027, just in time to celebrate the building’s centennial. While the details of the architectural program are currently being defined, it is to be hoped that the determination of decision-makers will enable the Institut d’art et d’archéologie to once again become a place for science in the making.

Alain Duplouy is reader in Greek archaeology at the University Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne. He was Alliance Visiting Professor in Greek archaeology at Columbia University during the winter-spring semester in 2022. He has led archaeological fieldwork programs in Greece (Itanos) and Italy (Laos and Pietragalla) and has published extensively on elites and citizenship in archaic Greece, as well as on university heritage.

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. State Nobility: Elite Schools in the Field of Power. Stanford University Press: Oxford.

Bruneau, Philippe. 1992. “L’archéologie grecque en Sorbonne de 1876 à 1914. Deux professeurs d’archéologie grecque”, in P. Bruneau (ed.), Georges Perrot. Maxime Collignon. Études d’archéologie grecque présentées par Philippe Bruneau. Picard: Paris, 7–43.

Collignon, Maxime. 1882. “L’enseignement de l’archéologie classique et les collections de moulages dans les universités allemandes.” Revue internationale de l’Enseignement 3, 256–270.

Collignon, Maxime. 1899. “L’archéologie à l’Université de Paris.” Revue internationale de l’Enseignement 37, 193–198.

Lewino, Walter. 2018. L’imagination au pouvoir. Editions Allia: Paris.

Martinez, Jean-Luc. 2009. “La gypsothèque du musée du Louvre à Versailles.” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1127–1152.

Texier, Simon. 2005. L’Institut d’art et d’archéologie. Picard: Paris.

Therrien, Lyne. 1998. L’histoire de l’art en France. Genèse d’une discipline universitaire, Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, Paris.

Photo: Wikimedia.org | Institut d’art et d’archéologie, Paris | artonthefly | licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Published on November 21, 2023.