Interpretive Archaeology: Historiography of the Ancient World

This is part of our campus spotlight on Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, with Columbia University.

This seminar was offered to University of Columbia students while I was the Alliance visiting professor there during the winter-spring semester of 2022. The objective of the seminar was to bring a historiographical dimension to the training of students enrolled in archaeology and art history of the ancient world or Classics, by providing them with the keys to various readings of ancient Greek societies and their material culture and the way these have been constantly renewed since the nineteenth century. Through class discussions of ancient sources and modern texts, the seminar developed ways of identifying the interpretive models that have shaped classical scholarship up to now. The seminar offered the opportunity to discuss these models, be they complementary or conflicting, in order to move towards an ever more explicit reasoning on the interpretations of ancient sources and archaeological evidence.

Course description

As post-processual archaeologist Ian Hodder once argued, interpretations of past material cultures and societies rest partially on social and cultural contexts in the present. They depend on the cultural background of scholars, on their education and responses to current issues, but also on their academic influences. In this sense, archaeology might be considered as a social practice that is concerned with meanings and making sense of things. Beyond this approach to archaeology, which stems from post-processual thinking—and risks leading to absolute relativism—this seminar mostly emphasizes the value of historiography, that is of how scholars have studied a particular subject using specific sources, techniques, and theoretical approaches. As background models applied to the interpretation of material culture are not always explicitly referred to in the writings of archaeologists—nor even sometimes consciously integrated and applied—historiography has become a specific field of research, worthy of consideration when reading other scholars’ works and evaluating them critically in relation to one’s own beliefs—which also have to be made explicit and fully scrutinized.

Interpretive models applied by classical archaeologists to material culture have fluctuated greatly since the late nineteenth century. Models often reflect contemporary debates in classical historiography, implying more general ideas about social structure, economy, politics, etc., which sometimes also correspond to national trends. A very clear illustration of this implication is the debate on the nature of the Greek polis. According to British historian Oswyn Murray (1990), “To the Germans the polis can only be described in a handbook of constitutional law; the French polis is a form of Holy Communion; the English polis is a historical accident, while the American polis combines the practices of a Mafia convention with the principles of justice and individual freedom.” Taking Murray’s description as a fil rouge, the seminar explores how past and current models have shaped discourse on the Greek city and its material culture. Two main themes are addressed during the semester through dedicated lectures, reading lists, class presentations, and group discussions:

- The cult of the dead: heroes, ancestors, and the ordinary dead

- Style and society: identity and community

These themes are further described as follows:

(a) The cult of the dead: heroes, ancestors, and the ordinary dead: Since the classical study of R. Hertz (1905-1906), we know that in every society there are interactions between the dead and the living. In ancient Greece, these interactions occurred through specific rituals. Death generates a disruption of the social and religious order, entailing the performance of various rituals to “normalize” the situation. Scholars have gradually established distinctions between the ordinary dead, family ancestors, and heroes. Whereas heroes are increasingly considered as gods—at least from a ritual perspective—“ancestors” are usually defined as “recently heroized deceased.” The category, which will be closely scrutinized throughout the seminar, appears as an interpretive “middle ground” between the ordinary dead and the heroes, mostly driven by kinship, lineage, and clan theories. Through the dedicated reading of milestone studies, we will investigate various aspects of the Greek cult of the dead and its links to the making of Greek communities.

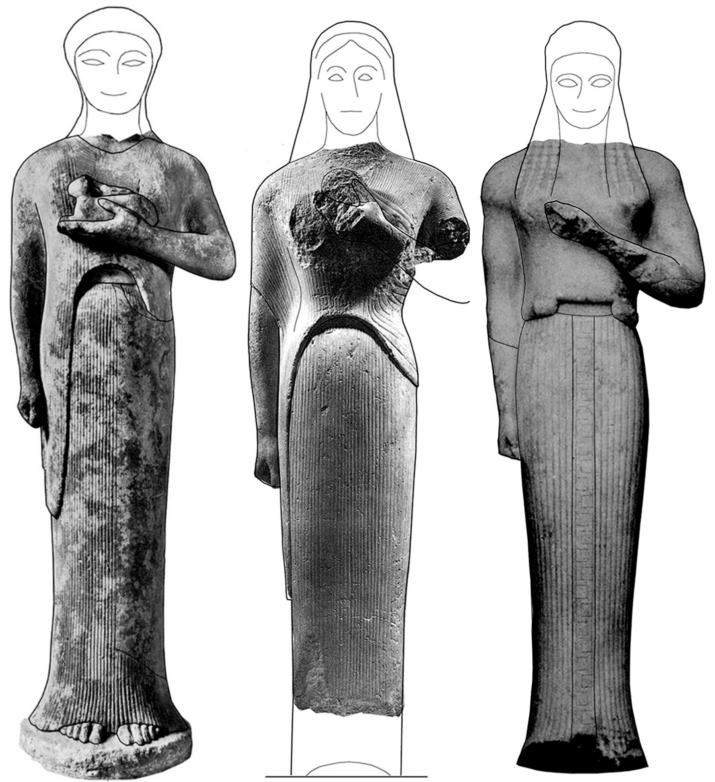

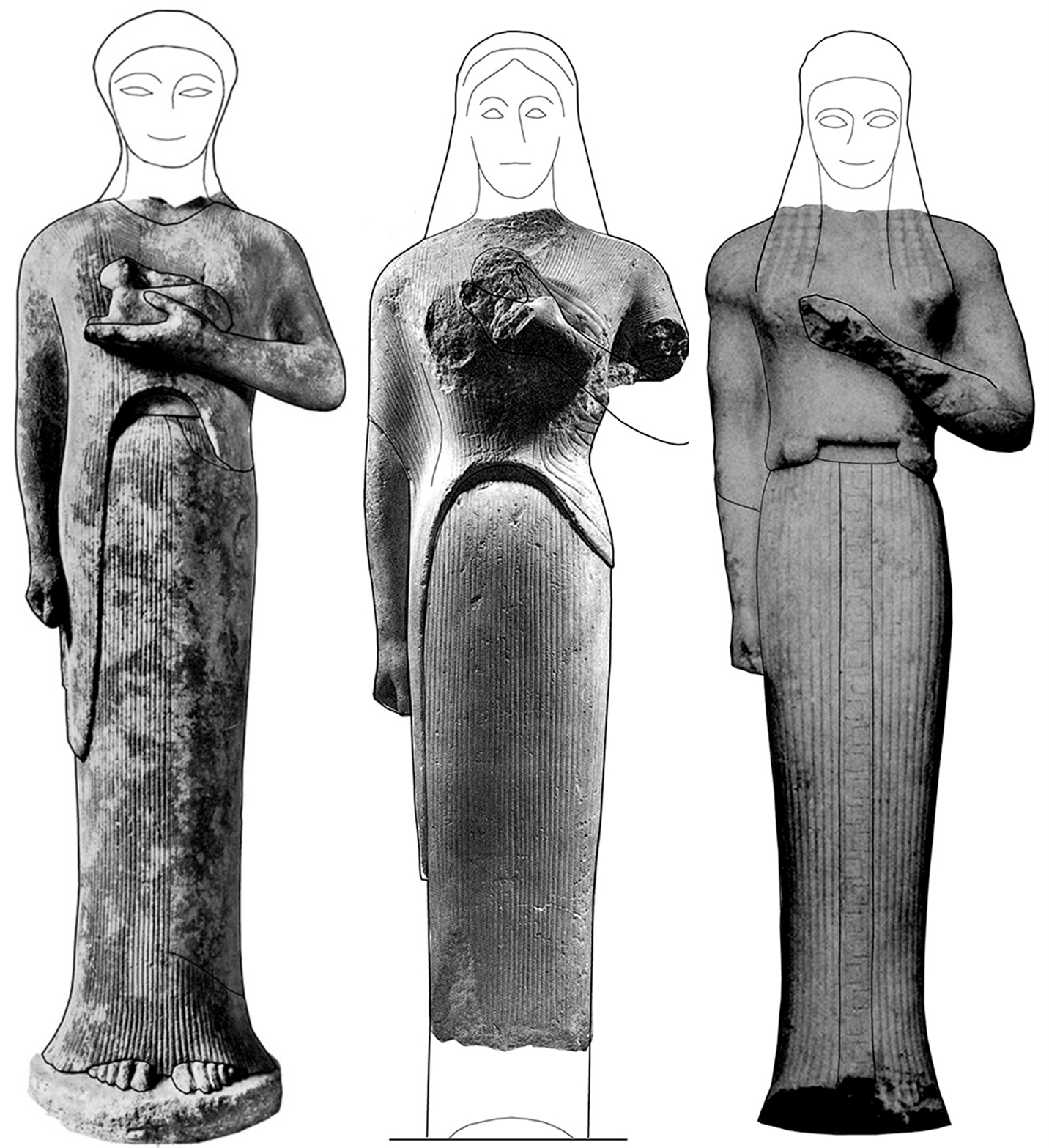

(b) Style and society: identity and community: Style is widely recognized as a powerful interpretive tool in studying material culture in relation to society, as it conveys, through forms and patterns, consciously or not, a message about collective identity. Here, anthropological scholarship meets Classical archaeology. Since the late nineteenth century, the classification of pottery and sculpture has emphasized the political segmentation of the Greek world into poleis, identifying Athenian or Corinthian vase painting, Samian or Parian sculpture, etc. Through the reading of classical texts, we will investigate the historical value of styles in pre-Classical Greece, as a tool to identify political and social aspects of Greek communities.

Course organization

The course is open to graduate students (as well as advanced undergraduate students) from the Art and Archaeology department and from the Classics department. It is also proposed as a graduate-level course to students from member schools of the Inter-University Doctoral Consortium (IUDC).

Beyond compulsory attendance, the seminar rests on active participation by students. Students are supposed to engage in class presentations of shared assignments. The final grade is based on class presentation (50%), participation in class discussions (20%), and a final research paper (30%) submitted during week FIFTEEN. Individual class presentations are based on teamwork, but the final research paper is strictly personal.

Course material

Most texts required for the preparation of this class have been made available as pdf files on courseworks. Students are also asked to consult books at Columbia University’s libraries.

Theme I: The cult of the dead: heroes, ancestors, and the ordinary dead (Weeks 6-8)

- N. Coldstream, “Hero-cults in the age of Homer,” JHS96 (1976), 8–17.

- Malkin, Religion and colonization in ancient Greece, Leiden, 1987, 189–266 (“The cult of the founder”).

- M. Antonaccio, “Contesting the past: Hero cult, tomb cult, and epic in early Greece,” AJA 98 (1994), 389–410.

- de Polignac, Cults, territory and the origins of the Greek city-state, Chicago, 1995, 128–149 (“The hero and the political: Elaboration of the city”).

- Mazarakis-Ainian, “Reflections on hero cults in Early Iron Age Greece,” in R. Hägg (ed.), Ancient Greek hero cult, Stockholm, 1999, 9–36.

- Whitley, “Too many ancestors,” Antiquity 76 (2002), 119–126.

- Ekroth, The sacrificial rituals of Greek hero-cults in the Archaic to the early Hellenistic periods, Liege, 2002, 303–341 (“The ritual pattern”).

Theme II: Style and society: identity and community (Weeks 12-14)

- R. Sackett, “The meaning of style in archaeology: A general model,”, American Antiquity 42/3 (1977), 369–380.

- Wiessner, “Style and social information in Kalahari San projectile points,” American Antiquity 48/2 (1983), 253–276.

- W. Conkey, “Experimenting with style in archaeology: Some historical and theoretical issues,” in M.W. Conkey and C. Hastorf (eds), The uses of style in archaeology, Cambridge, 1990, 5–17.

- N. Coldstream, “The meaning of the regional styles in the eighth century B.C.,” in R. Hägg (ed.), The Greek renaissance of the eighth century B.C., Athens, 1983, 17–25.

- M. Snodgrass, “Centres of pottery production in Archaic Greece,” in M.-C. Villanueva Puig et al. (eds), Céramique et peinture grecques. Modes d’emploi, Paris, 1999, 25–33.

- Rolley, “L’espace ou le temps. Points de vue sur la sculpture grecque archaïque,” Formes 2 (1978), 3–12.

- Croissant, “Style et identité dans l’art grec archaïque,” Pallas 73 (2007), 27–37.

Course schedule

Week ONE

Introduction to the seminar

- No reading

Week TWO

Historiography of the Greek city I: A glimpse into national trends

- Murray, “Cities of Reason,” in O. Murray and S. Price (eds), The Greek City from Homer to Alexander, Oxford, 1990, 1-25.

- Optional: V. Azoulay and P. Ismard, “Les lieux du politique dans l’Athènes classique. Entre structures institutionnelles, idéologies civique et pratiques sociales,” in P. Schmitt-Pantel and F. de Polignac (eds), Athènes et le politique. Dans le sillage de Claude Mossé, Paris, 2007, 271–309.

Week THREE

Historiography of the Greek city II: The making of the Greek city: reason and competition

- -P. Vernant, The origins of Greek thought, Ithaca, 1982, 9–11 (“Introduction”), 49-68 (“The spiritual universe of the polis”) & 130–132 (“Conclusion”). French original, Les origines de la pensée grecque, 1962.

- Murray, “History and reason in the ancient city,” PBSR 59 (1991), 1–13.

- Nietzsche, “Homer’s contest” (German original, Homers Wettkampf, 1872).

Week FOUR

Historiography of the Greek city III: The making of the Greek city: performance and behaviors

- Weber, “The distribution of power within the political community: Class, status, party,” in Economy and Society (ed. by G. Roth and C. Wittich), Berkeley, 1978, 926–939. German original, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 1921, 531–540.

- Duplouy, “Citizenship as performance,” in A. Duplouy and R. Brock (eds), Defining citizenship in archaic Greece, Oxford, 2018, 249–274.

Week FIVE

The cult of the dead—Introductory lecture: key sources and themes

- No reading

Week SIX

The cult of the dead—Student presentation and class discussion (Part I)

Week SEVEN

The cult of the dead—Student presentation and class discussion (Part II)

Week EIGHT

The cult of the dead — Student presentation and class discussion (Part III)

Week NINE

The cult of the dead—Final lecture: A case study: The necropolis of Vari

- No reading

Week TEN

Style and society—Introductory lecture: key sources and themes

- No reading

Week ELEVEN

Style and society—Student presentation and class discussion (Part I)

Week TWELVE

Style and society—Student presentation and class discussion (Part II)

Week THIRTEEN

Style and society—Student presentation and class discussion (Part III)

Week FOURTEEN

Style and society—Final lecture: Two case studies: Samos and Miletus

- No reading

Alain Duplouy is reader in Greek archaeology at the University Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne. He was Alliance Visiting Professor in Greek archaeology at Columbia University during the winter-spring semester 2022. He has led archaeological fieldwork programs in Greece (Itanos) and Italy (Laos and Pietragalla) and has published extensively on elites and citizenship in archaic Greece, as well as on university heritage.

Image: A comparison between Samian, Naxian, and Parian styles for korai, sixth-century female representations. Drawing by Francis Croissant.

Published on November 21, 2023.