An introduction to our special feature, Thinking Eurasia Now.

An introduction to our special feature, Thinking Eurasia Now.

Eurasia as a world and thought model

This special feature proposes multiple perspectives on Eurasia, the planet’s “largest landmass,” which is here broadly conceived of as a historical, political, and art-historical form of connectivity across the continental divisions of Europe and Asia and across the nation-states located on this territorial expanse. Departing from earlier historical narratives and existing models of connectivity, such as the Silk Road, this feature approaches Eurasia through contemporary debates and artistic projects, be they in the realm of (science) fiction, film, geopolitics, or intellectual history. The feature also examines responses to expansionist narratives such as that based on the concept of Eurasianism, which designates both a desire to challenge Western domination and to affirm a new imperial order in the post-Cold War context. The contributions address not only geopolitical tensions but also the ways in which Asia and Europe intersect, for example in debates on modernity and in the arts. To think Eurasia also entails a reconsideration of world models that are emerging in the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic and post-globalization environmental and geopolitical crises. Together, the pieces included here go beyond an understanding of the world as a place of power struggles between East and West over global supremacy and focus instead on issues of collaboration and convergence through an emphasis on futurity.

Post-Cold War East-West constellations

In the midst of the Ukrainian-Russian war and against the backdrop of escalating diplomatic tensions between China and the US, which entail “new imperialist” struggles for the control of the Pacific (The Guardian, July 27, 2023), shadows of Cold War divisions are coming back, prompting debates about models of post-Cold War world organization. These debates are permeated by the role of Eurasia in the new East-West constellations. In the summer of 1989, Francis Fukuyama published The End of History and the Last Man as an essay. He developed it into a book in 1992, famously predicting the rise of liberal democracy as a uniform model of state organization in the context of the weakening and eventual collapse of the communist regimes that divided the East from the West. Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, Fukuyama has updated his thesis to predict an “end of an end of history” in the event of possible political alliances between the former giants of the Cold War bloc. He has further posited that these alliances could degenerate into another world war. His initial thesis was most famously criticized by economist Samuel Huntington (1992 & 1996), who advanced that the civilizational and cultural—especially religious—differences that came with the loosening of state borders were becoming more pronounced. Huntington has drawn his own share of criticism from, among others, cultural theorist Edward Said, who rebutted Huntington’s thesis in his 2001 “The Clash of Ignorance.”

The question of East and West civilizational clashes was first put front and center by early twentieth-century narratives of cultural pessimism such as Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West. This two-volume magnum opus written in 1918 and 1922 delineated the inevitable rise and then decay of world civilizations, culminating in what Spengler called “a decline of the West.” However, these arguments in favor of an East-West world division were seemingly contradicted—especially before the COVID-19 pandemic and the intensification of the Russian- Ukrainian war in 2022—by new possibilities of connectivity between China, Russia, and Europe, possibilities defined by Portuguese scholar and politician Bruno Maçães (2018) as “Eurasia.”

Published in 2018, Maçães’s book The Dawn of Eurasia: On the Trail of a New World Order allows us to reflect on the possibilities of convergence among China, Russia, and Europe, rather than on divergence. Maçães predicts a future “Eurasian age,” going back to earlier models of world connectivity and to shared values prevalent in the Old World. These values had already been envisioned by German explorer Alexander von Humboldt in the social sciences, but Maçães imports them into other fields such as history, politics, and the arts (Maçães 2018). During a voyage through the Eurasian sphere that took him from Astrakhan—the historical gateway to the Caucasus—to Khorgos (Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in China), Maçães probes his thoughts about the respective unity of Europe, China, and Russia and about their different visions of political order within a shared global space (Ibid.). As Maçães claims, The Dawn of Eurasia is a book about “the reunification of Europe and Asia as modernity became universal” (interview with the author, August 2023); for him, it is no longer possible to posit a unique model of world organization; instead several models have emerged.

Eurasia then and now

Thinking Eurasia Now seeks to mediate between multiple world visions. Some historians have assessed that there was a balance of power between Asia and Europe until around 1750-1800. At that time, Europe came to maximize its economic potential through the successful exploitation of resources at home—mostly coal— and the development of new trading opportunities with the New World (see Pomeranz 2000 or Frank 1998). In fact, the rise of the West at the turn of the nineteenth century has been seen as a blip in history, as opposed to the sustained rise of Asia (Frank 1998). What is the relevance of Eurasia today, and how do the possibilities offered by the idea of a Eurasian utopia help address the world’s divides? If globalization is understood as an age of contagion, culminating in the viral propagation of media and the spread of COVID-19 (Kim 2022), how are we to reflect on Eurasia and its potential upon the exhaustion of the forces of globalization?

In response to these interrogations, social anthropologist Chris Hann discusses Hungary and Ukraine as “two countries at the interface of Europe and Asia” to draw attention to two conflicting definitions of Eurasia: some regard Eurasia as a continuum—a “supercontinent”— while others see Eurasia as signifying an inescapable separation between Europe and Asia, which for Hann is rooted in Greek antiquity. He also explains that Eurasia is defined today—from a Western perspective—as “whatever lies east of Western Christianity” and that it is usually politically associated with illiberalism. Hann’s own affinity lies with the supercontinental approach, i.e. with a definition of Europe as a Eurasian macro-region territorially on par with China or South Asia. Alternatively, intellectual historian Noriaki Hoshino, in his article that explores the role of the Japanese New Middle Ages in creating a “Eurasian intersection,” understands Eurasia as a tug between Europe and Asia and draws implications for this intersection in relation to theories of modernity and world models.

In the ancient world, the Silk Road, celebrated in most contemporary references to Eurasia, was one of the earliest projects connecting East and West. Today, the world of ancient empires, especially as it emerged in the course of early forms of globalization that linked Europe to the Islamic world and China, still dominates many accounts of Eurasian connections. Political scientist Barbora Valockova reminds readers that “the Silk Road had its eastern terminus in Chang’an (today’s Xi’an), while its western endpoint was in Daqin, the Chinese name for the Roman Empire.” However, since 2013, the revamping of the idea of the Silk Road via the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) proposes a new narrative for connecting the world. However, despite fantasies about East-West connections such as the BRI, the specter of religious and political divisions lingers, for example in relation to the presence of Islam in the Eurasian world, which has been contested in the modern world.

The BRI is meant to rebuild the old Silk Road, which connected China with Europe through many other countries in Asia. However, with China massively investing in infrastructure for roads and shipping routes in those Asian countries, recent critics have described the BRI essentially as a tool of Chinese global dominance rather than as a connector (The Guardian, July 27, 2023). Italy, the only major Western member of the EU to be part of the BRI, is currently seeking to dissolve its ties to the agreement because of an increase in non-reciprocal economic advantages in its commercial relation with China. As Valockova explains in her essay, initially the US strongly opposed Italy’s signing of the BRI Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with China but was eventually reassured when Italy was able to use a text for the agreement that it had itself formulated and that extolled “Western principles and standards.” China did not have a problem with this wording; hence both the US and China were satisfied with the terms of the agreement. In this context, Valockova reads Eurasia as a “norm neutralizer,” which means that it allows Europe—via the EU—to balance the US’s and China’s powers without it becoming an appendage of either countries. It is precisely these fears of becoming marginalized in the face of Asia that motivated the EU Council to produce The Project Europe 2030 Report. This report signals Europeans’ anxieties that “the Union and its Member States could slide into marginalization, becoming an increasingly irrelevant western peninsula of the Asian continent” (Diesen 2021, 24).

As Europe has inspired Asia to reflect on its own identity, Asia has in turn prompted Europe to do the same. In his article, Hoshino shows that Japan responded to Fukuyama’s predictions by deriving its own world model in the aftermath of the Cold War—a model drawn from the European New Middle Ages and from a desire for a unified ideology in Japan. According to one of the characters in a short-story written by Berlin-based multilingual writer Yoko Tawada (2002) which documents a dream Trans-siberian journey—Where Europe begins—“everything’s Europe behind the Ural Mountains.” The question of European identity is thus tied to Asia through many streams, including Russia’s own historical attempts to get closer to Europe under Catherine and Peter the Great, as well as through debates about modernization and modernity. Beyond religious and economic divisions, the question of the differences between Asia and Europe has remained constant in attempts to define Eurasia. According to the curators of the exhibition Eurasia, a landscape of mutability, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp (M HKA) in 2021, “In contrast to nation states, Eurasia is ambiguous, home to a growing number of new modernities and spheres of influence.” The curators further stated that “We can become aware of the historical notions of Eurasia, Eurasians and Eurasianism, in all their utopian and dystopian forms, but we should also look to seize their futurity.”[1]

Futurity and “SF”

Eurasia is presented here as to undermine the contours of a Western-centric, US-dominated world and opens new avenues for thinking about an intersectional world. The process of decentering the West is applied to major “European” ideas such as cosmopolitanism and modernity, which are re-translated and/or re-imagined in Asian contexts. In her interview, filmmaker and scholar Soyoung Kim asks how global intellectuals can engage with the subaltern cosmopolitanism of non-Western, Soviet, and nomadic Central Asia. In her work, Kim compares the histories of colonialism and the persecution of Korean ethnic minorities in Central Asia under Stalin to those of other persecuted minorities that were deported from different European countries under Stalin’s rule. Kim describes her three-channel installation SFdrome: Ju Sejuk as constitutive of an archive of the future that documents the life of a socialist feminist personality who was sent into exile to Kazakhstan by Stalin, to a place that happens to be the site from which the largest rocket was launched from Earth into space: the Baikonur Cosmodrome. In her title, the abbreviation “SF” stands for a range of meanings: “string figures, science fact, science fiction, speculative feminism, and speculative fabulation” (Kim 2020). Kim’s work examines, among other topics, the spaces in Central Asia where ethnic Koreans were sent in exile under successive regimes—Japanese, Stalinist, and post-Soviet nationalist. Thus, her work highlights Eurasia as a place of exile but also as a place of communion and solidarity for a range of minorities who reconnected there and created ties between Western and non-Western worlds.

The rise of postcolonial and decolonized identities has impacted not only minorities in Asia but also, more broadly, the relation between Asia and the West, especially as this relationship developed after WWII. It is this connection that Holger Briel studies through science fiction (SF). The media theorist shows that this literary genre is an ideal field of inquiry for examining post-WWII decolonized and postcolonial imaginaries, in particular because non-western SF worlds have dismantled the primacy of an American-led, Orientalist vision of science fiction. In particular, Briel discusses the emergence of Sinofuturism (another “SF”) as a critical step in studying Eurasia(nism) as an opposition to Western-centric paradigms. For him, Sinofuturism is part of the broader development of Chinese SF, here understood as science fiction and speculative fiction constituting a platform to envision the future across multiple ecological zones and various potential utopias and dystopias. The outcome of this envisioning, as Briel writes, is not a world based on competition between East and West but rather a world based on multiple futurities.

New perspectives on Eurasianism

Eurasian futures are encapsulated in the term Eurasianism, which is most frequently associated with Russian thought. “Classical Eurasianism” was first developed by Russian émigrés in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. The concept “proposed an alternative to Western colonialism and Soviet modernity by advancing the idea of Russian messianism” (Filimonova 2015, 118). After the fall of the Soviet Union, the uniqueness of Russia, as well as its centrality in Eurasia and distinct role in both Asia and Europe, served as a catalyst for “neo-Eurasianism.”

This new Eurasianism encompasses an innate coherence uniting most of the lifespace of the former Russian Empire and is considered from multiple novel perspectives by the feature’s contributors. In her essay on Georgian-born Sergei Paradzanov, cultural studies scholar Adrianna Hlukhovitch examines Eurasia(nism) as a doctrine that holds together, through the cinema of former Soviet republics, the center of the Soviet Union. Hlukhovytch shows how Paradzanov’s poetic cine-essays are deeply political in the way they expose the Soviet grip on Ukrainian and Central Asian territories and undermine Eurasianism through ancestral myths and ethnic motifs. In fact, Russia has used the pretext of Eurasianism and the establishment of an alternative (non-Western) world order to wage war on Ukraine. Echoing this thought, Hann’s specific treatment of Ukraine and Hungary underscores the ways in which doctrines of Eurasianism have played a significant role in shaping Russian nationalism in the post-Soviet era, especially in Hungary. Hence, the conceptualization of Eurasia has “function[ed] as a stigma for any political system that [has fallen] short of liberal democratic standards as specified in the West.” Looking at Ukraine, which Huntington identified as a west-east “fault line” in his projected “clash of civilizations,” Hann reveals the duplicity of the western call for liberal democracy. Ukraine has historically been a politically and religiously divided country; but it has been propelled into a unified symbol of liberal freedoms as a result of Russia’s attacks.

Many have suggested that the coexistence of Europe and Asia will be crucial for our experience of the twenty-first century and that Eurasia will bring back a sense of unity that was lost with the deflated powers of globalization. While warning of the reactionary potential of Eurasianism, Thinking Eurasia Now proposes various intellectual and artistic projects to assess how Europe and Asia may converge in the future. However, with the end of the Cold War and the accelerated rise of Asia, questions emerge about the possibility that this coexistence might become Asian-centered, making Eurasia ever more relevant for an understanding of the relationship between Europe and Asia on a continuum.

Work on this special feature was facilitated by the start-up research grant UICR0700027-22.

Research

- “Eurasia as a ‘Norm Neutralizer’ in the Relation between Europe, the US, and China” by Barbora Valockova

- “Exploring the New Middle Ages: Japanese Intellectual Discourses and the Eurasian Intersection” by Noriaki Hoshino

- “The Poetic Cinema of Sergei Paradzhanov: An Opportunity to Rethink Eurasia” by Adrianna Hlukhovych

- “Asian Futures or Western Futures? The Increasingly Varied Faces of Science Fiction” by Holger Briel

Commentary

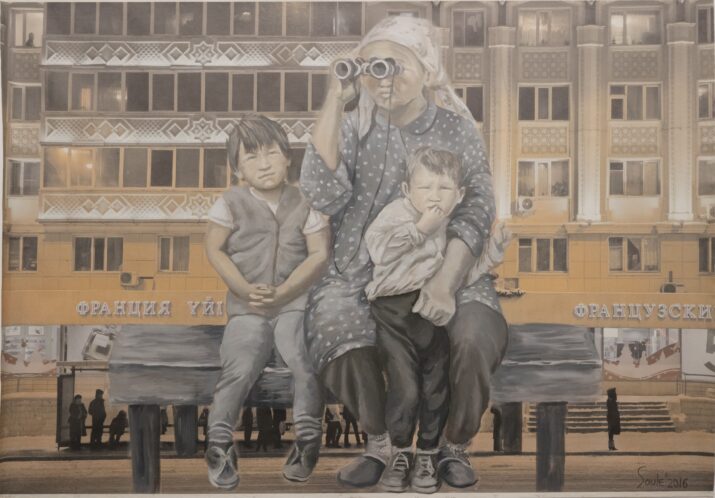

Visual Art

Fiction

Poetry

Interviews

Campus Round-Up

Arina Rotaru is an Assistant Professor at Beijing Normal University-Hong Kong Baptist University, United International College, who earned her PhD in German Studies and Comparative Literature from Cornell University and her BA from the University of Bucharest. Her research interests include comparative modernities, minoritarian avant-gardes, world literature and film, and diasporic poetics.

References

Diesen, Glenn. 2021. “Europe as the Western Peninsula of Greater Eurasia.” Journal of Eurasian Studies, 12, no 1, 19–27.

Eurasia. A Landscape of Mutability. 8 Oct 2021–23 Jan 2022. muhka.be/programme/detail/1452-eurasia-a-landscape-of-mutability.

Filimonova, Tatiana. 2015. “Eurasia as Discursive Literary Space at the Millenium.” In The Eurasian Project and Europe: Regional Discontinuities and Geopolitics, 117–132.

Frank, Andre Gunder. 1998. ReORIENT: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Oakland, CA: California University Press.

Fukuyama, Francis. 1989. The National Interest, no. 16, 3–18.

Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. Free Press.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1993. “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Affairs, 72, no. 3, 22–49.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Kim, Soyoung. 2020. “Post-contact zones: (en)countering COVID-19.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 21, no 4, 557–565. DOI:10.1080/14649373.2020.1831813.

Maçães, Bruno. 2018. The Dawn of Eurasia: On the Trail of the New World Order. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pomeranz, Kenneth. 2000. The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Said, W. Edward. 2001. “The Clash of Ignorance.” The Nation. October 4, 2001. The Clash of Ignorance | The Nation.

Spengler, Oswald. 1926–1928. 2 vols. The Decline of the West. New York: A. A. Knopf.

Tawada, Yoko. 2002. “Where Europe Begins.” In Where Europe Begins. Trans. Susan Bernofsky and Yumi Selden. New York: New Directions. 121–147.

The Guardian. 2023. Italy seeking to leave “atrocious” China Belt and Road plan without harming ties – minister | Italy | The Guardian. The Guardian July 31.

The Guardian. 2003. Emmanuel Macron denounces “new imperialism” in Pacific on historic visit to Vanuatu | Pacific islands | The Guardian. The Guardian July 27.

[1] muhka.be/programme/detail/1452-eurasia-a-landscape-of-mutability.

Image: Saule Suleimenova

Published on September 12, 2023.