This is part of our special feature, Thinking Eurasia Now.

Translated from the Turkish by Brendan Freely.

That morning as Monsieur Lausanne was on his way to the Karaköy Post Office to send Dilara Hanım a telegram, he saw a row of rowboats loaded with coffins move away from the shore towards Üsküdar one after the other. The rowboats loaded with coffins wrapped in green flags bobbed up and down on the waves like a chain of death.

He asked a man standing nearby what these rowboats were.

“Corpses,” said the man, “the corpses of soldiers who don’t want to be buried in Europe, who want to have their eternal rest in Asia, on Muslim soil . . . They’re taking them to the far shore to be buried.”

Lausanne didn’t quite understand what the man said but he didn’t want to ask too many questions, he was going to say, “There are Muslim cemeteries in the European part of Istanbul, aren’t they Muslim soil?” but he changed his mind.

He went to the post office and sent Dilara Hanım a brief telegram.

“The foreign minister has invited me to dinner this evening. Matters that interest you will be discussed. If you should wish to attend, it would be a great pleasure and honor for me to accompany you.”

Dilara Hanım, who informed him that she would be “pleased to come,” was in a strange mood in those days, the war made her worried and anxious about Ragıp Bey, and this anxiety increased her yearning in a painful manner.

There was nothing strange about either her anxiety or her yearning, but she had an unusual way of coping with it, with a strength of will seldom seen in people experiencing this kind of yearning, she concealed her feelings about Ragıp Bey from herself, from her own consciousness, she tried to bury them somewhere in her soul and cover them up, and for the most part she was successful. The yearning never abated, it was always there, sometimes it manifested itself as a sudden pain that seemed to rip through her, sometimes as an unbearable anguish, but this did not affect the flow of daily life that Dilara Hanım insisted on maintaining.

She rejected the idea of being a recluse or a lonely woman who spent her life with her daughter and son-in-law so violently that this denial and her yearning were constantly clashing, apart from momentary victories, the yearning usually had to accept defeat and retreat. The denial was more suited to Dilara Hanım’s personality, ideas and habits, in any event the yearning behaved in a hostile manner to her, as if it was a stranger, or as if it belonged to someone else, in this war that was raging within her she sided with denial, she supported it.

Unavoidably, this created a sense of partition within her, it wearied her to constantly struggle to bury one of her emotions deep within her; this weariness led her not to give up on life but to cling to life more violently.

Sometimes she blamed Ragıp Bey for being the cause of all this and got angry at him, but at other times she thought that he was right, her weakest moments were the moments when she accepted that Ragıp Bey was right, at those times she wasn’t able to prevent the yearning from taking her over, all of her resistance was broken, she blamed herself. “Why,” she asked. “why did I behave that way?” These questions inevitably paved the way for the unending questions, “Why am I like this, why do I harm myself, why do I obstruct my own happiness?” She didn’t want to find the answer to these questions, she was afraid, because at those times she felt that if she questioned herself a bit more she might come face to face with her own truths. She already knew what those truths were, but every time she faced them they caused her pain and wore her out, and it didn’t produce any outcome, nothing changed, that’s why she avoided it if at all possible.

When she remembered one of those moments she said to Osman, “People’s relationship with themselves is like their relationship with death, they know the truth but they don’t accept the truth, they prefer to forget the truth.”

She stopped and then continued, “Because they can’t live with that truth. Is it possible to live feeling death at every moment, knowing that it’s coming, it’s approaching, that it’s inevitable? You have to forget that truth and bury it deep in your consciousness, the truth about yourself is like that too, you feel it, indeed you know it, but no one can live with that truth . . . No one can bear to know the whole truth about themselves. We have to forget ourselves, trick ourselves, we have to see ourselves as someone we’ve made up in our minds.”

Her face suddenly fell, “I hate picking myself apart, because of Ragıp I had to think about things like that, I’ll never forgive that,” she said angrily.

She hadn’t changed her lifestyle when she was with Ragıp Bey, and she didn’t change it after Ragıp Bey left, after her husband died she had distanced herself from the crowds; this was a vague, twilight area that was observed by no one, the entirety of which no one saw, Dilara Hanım’s own life was like a private garden in which she lived as she pleased without showing anyone and without asking anyone. Those who were given permission to enter the garden only saw part of it but they couldn’t explore all of it.

The fortune her husband had left her had helped develop this garden’s thick walls, “Wealth shields you,” she said once to Osman, “money is good for buying your liberty, if you ask me it’s not much good for anything else.”

After Ragıp Bey left, this twilight area, which she saw as the most precious part of her existence, which she defended with an almost mad passion and had hidden from everyone, began to seem like her enemy, “I couldn’t bring liberty and happiness together,” she said to Osman, “What use is liberty that doesn’t bring happiness? It’s such a simple question, but only idiots think there are simple answers to simple questions. They don’t realize that sometimes it’s impossible to find an answer to a simple question. Yes, when there’s no happiness, liberty is rendered meaningless, but is happiness that destroys liberty of any use, there’s that question too.” She paused, she thought, she allowed her frail and transparent body that came from the world of the dead to ripple in the wind, then continued, “perhaps I didn’t want happiness,” she said, “liberty is uneasy and vague, it doesn’t give a person any sense of security, it keeps its door open to all dangers, yes, that’s how it is, happiness requires you to close some doors within yourself, I was never able to close those doors, in my opinion I’m attached to liberty in an unhealthy way, I’m fond of that ambiguity and danger . . . That’s why I could never reach happiness, no that’s not completely true, there were times when I did reach it, I was happy with Ragıp, I’d closed the doors, but he wanted me to close all my doors. He never understood that this was impossible for me . . . Yet I still liked happiness, perhaps even more than I liked my liberty . . . But I could never digest the idea of giving up my liberty . . . This contradiction, this peculiarity in my nature determined my entire fate . . . Everyone has some kind of madness, well this is mine, believing that happiness and liberty can’t coexist.”

In these days full of contradictions. of internal reckoning and of emotional uprisings that she tried to put down, Monsieur Lausanne was struggling to get into her twilight garden as an insistent guest, and in a sense he was succeeding too.

He was a very well-informed and entertaining man, like most journalists he had a lot of stories to tell, a lot of experience, because of his profession he wasn’t intimidated by obstacles, if he was stopped he would find another way around, he had a likeable predacity, he thought he had a right to ask and do anything, he had a self-indulgence that was decorated with intelligence. His responsibility in his work, his success in breaking news and his fame made him trustworthy.

He had the means to bring Dilara Hanım to the places where the people who knew most about the war were to be found. Because of Ragıp Bey, the war was slowly becoming a passion for Dilara Hanım, and he was perhaps the only person who could satisfy her desire to obtain the latest news.

Without realizing it, he was entering Dilara Hanım’s life on a path that had been cleared by Ragıp Bey, he was exploring that twilight area because he had the means to ease her worries and anxieties about Ragıp Bey. But to say that this was all there was would be unfair to Monsieur Lausanne, his presence and his conversation affected Dilara Hanım, he was succeeding in establishing a place for himself on the shore of that vast area of Dilara Hanım’s soul that Ragıp Bey overspread.

Dilara Hanım was aware of the situation, and it both pleased her and made her uneasy. She couldn’t quite grasp why she was uneasy, but the pleasure that seeing Monsieur Lausanne created in her had something saddening about it, after Ragıp she didn’t want any man to create a stirring of emotion within her, but she didn’t reject any joy that helped obscure the ache that Ragıp Bey had created. As Osman also said, she was full of “contradictions.”

That evening they went together to the dinner at Foreign Minister Noradinyan Efendi’s house. The guests who came to the mansion in Taksim had to wait some time for their host. Noradinkyan Efendi arrived with a yellowed face and apologized for being late.

“Unfortunately we’re living through one of the most difficult times in our history,” he said, “our army is retreating towards Lüleburgaz. This shouldn’t have happened, our European friends shouldn’t have left us alone, they know how much we’ve struggled for peace but the Balkan states wanted war.”

To get clearer information Lausanne asked, “What is the Ottoman army’s current situation?”

The Foreign Minister was inviting foreign diplomats and journalists to develop a pro-Ottoman campaign in the eyes of both governments and peoples to force Europe to help. If he concealed the truth he wouldn’t be able to request this help, but if he told the truth he would be announcing the Ottoman Empire’s helplessness to the entire world.

“As you already know, the Bulgarians have taken Kırkkilise, there have been local skirmishes as our army retreats to the Lüleburgaz line. At Lüleburgaz our units will be reorganized and will give the enemy the answer they require . . . But it’s in Europe’s hands to make sure that too many people don’t die in this war, by putting pressure on the Balkan nations that wanted and started this war they could force them to end the war. From the beginning of this war we have shown the entire world that we want peace and that our intentions are good . . . However, the world has remained deaf to this.”

Then, evidently thinking that he should threaten as well, he continued.

“The Ottoman Empire is not an empire that can be overthrown by four Balkan nations, the world couldn’t contend with the death of the Ottoman Empire, the order and stability of the entire world would be shattered.”

This was met with complete silence. No one answered. It was clear that just as Noradinkyan Effendi hadn’t found the assistance he sought in official meetings, he wasn’t going to find it in these private gatherings either.

The German Ambassador suddenly said in a deep voice, “If the Ottoman foot soldiers had anything to eat this war wouldn’t have turned out this way.”

Monsieur Lausanne’s nationalism tended to raise its head especially when he was faced with Germans.

“If food hasn’t reached the soldiers, whose responsibility is that, Monsieur Ambassador? The quartermaster corps . . . If the quartermaster corps is at fault so is the army it’s part of . . . If we consider the German generals in the army, then it’s clear that these are German mistakes.”

The Foreign Minister intervened before the Ambassador could answer, the last thing he wanted was for this gathering to become a German-French duel and for the guests to argue among themselves.

“At the moment we’re not in a position to look for who is at fault,” he said, “that will be for later, of course our army will take the required steps to achieve the required results. Our mission at the moment is to bring about peace. By explaining this situation to your governments you can convince them that they can help in achieving this peace.”

Again he received no answer.

At dinner Dilara Hanım was seated next to the foreign minister, she took the opportunity, leaned towards the minister and asked the question she was most curious about.

“Have there been many fatalities among the men?”

Noradinkyan Efendi made a face.

“I don’t know how to answer that question, should I say thankfully or should I say unfortunately . . .”

It was clear the foreign minister was very distraught, he seemed wearied by the truths he knew.

“We haven’t had too many losses, indeed we’ve had very few losses. We lost almost no men when we left Kirkkilise to the Bulgarians. We had some casualties, but they were more because of some unpleasant incidents that occurred during the retreat.”

“Have there been many casualties among the officers?”

Noradinkyan Effendi suddenly leaned back and looked at Dilara Hanım with suspicion, he didn’t understand why was she asking so many questions, why she was interested in these kinds of details.

When Dilara Hanım saw the expression on the minister’s face, she felt the need to offer an explanation.

“I have a close friend at the front . . . I haven’t heard from him in a long time.”

Noradinkyan Efendi sensed the woman’s sorrow,

“What’s his rank?”

“I don’t know, I suppose he’s a colonel . . . Or something like that.”

“As far as I know we haven’t lost any officers of that rank. You can rest assured . . . At the moment we’re not losing men, all we’re losing is the empire’s territory and pride.”

No one would have guessed that someone could be this delighted by news of a war being lost, but Dilara Hanım had rarely in her life been this delighted. For her the person she missed was much more precious than an empire, “Patriotism,” she’d said to Osman, “what an absurd word, it’s one of the names men invented for their own death games, I wouldn’t have traded Ragıp for the entire Ottoman Empire . . . And do you want me to tell you something, every woman who had someone she loved at the front thought the same as I did, anyone who didn’t couldn’t be called a woman, in fact I don’t think they could be called human beings, but because men have a different conception of humanity, they keep talking about the necessity of death, that we need to be pleased by these deaths . . . They say it brings a person honor, I say men are idiots, for a sane person, what could be more precious than the life of someone you love?”

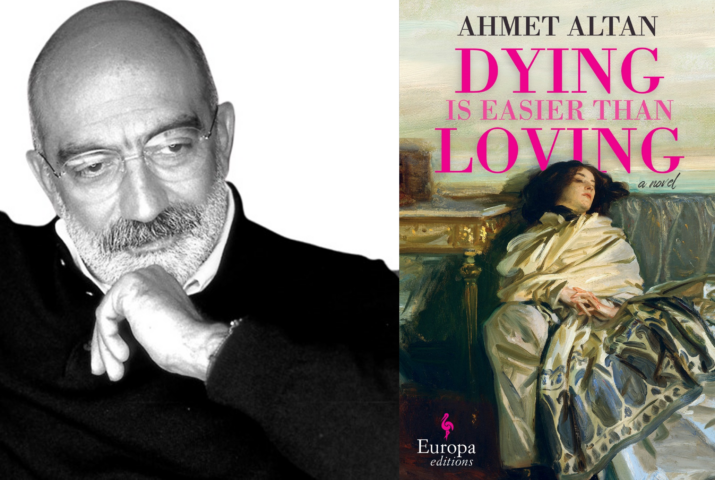

Ahmet Altan is one of today’s most important Turkish writers and journalists. He has been an advocate for Kurdish and Armenian minorities and a strong voice of dissent in his country; his arrestation in September 2016 and sentence to life in prison received widespread international criticism, with 51 Nobel laureates signing an open letter to Turkey’s president calling for his release. He was released in April 2021. Altan is the author of ten novels—all bestsellers in Turkey—and seven books of essays. In 2009, he received the Freedom and Future of the Media Prize from the Media Foundation of Sparkasse Leipzig, and in 2011 he was awarded the International Hrant Dink Award. The international bestseller Endgame was his English-language debut, and was named one of the fifty notable works of fiction of 2017 by The Washington Post. Like a Sword Wound is the winner of the prestigious Yunus Nadi Novel Prize in Turkey.

Brendan Freely was born in Princeton, New Jersey, and studied psychology at Yale University. He has been working as a freelance literary translator since 2004 and has translated over twenty books. He is also co-author, with John Freely, of Galata, Pera, Beyoğlu: A Biography about the social history, architecture, and topography of the Beyoğlu district of Istanbul.

This excerpt from DYING IS EASIER THAN LOVING was published by permission of Europa Editions. Translation copyright © 2022, Europa Editions.

Published on September 12, 2023.