This is part of our special feature, Homelessness and Poverty in Europe.

Translated from the French by Nina Bogin

Displaced persons

From the little Austrian village where we arrived from Hungary, we take the coach for Vienna. The mayor of the village pays for our tickets. During the voyage my little daughter sleeps on my lap. All along the road, luminous mileposts flash by. I have never seen such mileposts before.

When we arrive in Vienna, we go to a police station to announce our presence. There, in the office, I change my baby’s diapers and give her her bottle. She throws up. The policemen give us the address of a refugee center and tell us which tramway will take us there for free. In the tram, well-dressed women take my baby on their laps, they slip money into my pocket.

The center is a large building that must have been a factory or a barracks. In immense rooms, straw mattresses are spread out on the floor. There are collective showers and a vast dining hall. At the entrance to the dining hall is a blackboard stuck with notices of missing persons. People are looking for relatives and friends they lost contact with during the border crossing, beforehand or afterwards, in the city of Vienna, or even in the crowd and the chaos of the center.

My husband, like everyone else, spends his days waiting in the offices of different embassies in order to find a host country. I stay with my little daughter who lies on the straw mattress and babbles as she plays with bits of straw. I am obliged to learn a few words of German to ask for what I need for the baby. Taking her in my arms, I enter the center’s big kitchen and say to the man who seems to be the manager: “Milch für Kinder, bitte.” Or “Seife für Kinder.” The man always gives me personally what I ask for.

Christmas is coming when we take the train to Switzerland. There are fir branches decorating the little shelf in front of the window, and chocolate and oranges. This is a special train. Aside from the people accompanying us, the only travellers are Hungarians, and the train makes no stops until the Swiss border. There, a fanfare welcomes us, and kind women hand goblets of hot tea through the window, and chocolate and oranges.

We arrive in Lausanne. We are lodged in a barracks high above the city, next to a soccer field. Young women dressed like soldiers take our children with reassuring smiles. Men and women are separated for the showers. Our clothes are taken away to be disinfected.

Those among us who have already lived through a similar experience confess later on that they have been very frightened. We are all relieved to find each other again afterwards and, above all, to find our children, clean and already well fed. My little girl is sleeping peacefully in a beautiful crib the likes of which she has never had before, next to my bed.

On Sunday, after the soccer game, the spectators come to look at us through the barracks fence. They offer us chocolate and oranges, naturally, but also cigarettes and even money. It no longer reminds us of concentration camps, but of a zoo. The more modest among us refrain from going out into the courtyard, while others spend their time reaching their hands through the fence and comparing their bounty.

Several times a week, factory owners come looking for workers. Friends and acquaintances find a job and a flat. They depart, leaving their addresses.

After a month in Lausanne, we spend another month in Zurich, lodged in a school in a forest. We are given language lessons, but I can attend only rarely, because of my little girl.

What would my life have been like if I hadn’t left my country? More difficult, poorer, I think, but also less solitary, less torn. Happy, maybe.

What I am certain of is that I would have written, no matter where I was, in no matter what language.

The desert

From the refugee center in Zurich, we are “distributed” to places all around Switzerland. This is how, by chance, we come to Neuchâtel, more precisely to Valangin, where a two-room apartment, furnished by the inhabitants of the village, awaits us. A few weeks later, I begin work at a clock factory in Fontainemelon.

I get up at five thirty. I feed and dress my baby, I get dressed too, and I catch the six-thirty bus that will take me to the factory. I leave my child at the crèche and go inside the factory. I come out again at five in the evening. I pick up my little girl at the crèche, I take the bus again, I go back home. I do the shopping at the village shop, make the fire (the apartment does not have central heating), prepare the evening meal, put the child to bed, do the washing-up, write a little, and I too go to bed.

The factory is a good place for writing poems. The work is monotonous, you can think about other things, and the machines have a regular rhythm that accentuates the lines of verse. In my drawer I keep a sheet of paper and a pencil. When the poem takes shape, I note it down. In the evening, I copy it out in a notebook.

We are about ten Hungarians who work in the factory. We sit together during the lunch break at the canteen, but the food is so different from what we are used to that we eat almost nothing. In my own case, for at least a year, I have only coffee with milk and some bread for the mid-day meal.

At the factory, everyone is kind to us. They smile at us, they speak to us, but we don’t understand.

It is here that the desert begins. A social desert, a cultural desert. After the exaltation of the days of revolution and escape, come silence, emptiness, nostalgia for the days when we felt we were participating in something important, even historic, homesickness, and the lack of family and friends.

We were waiting for something when we arrived here. We didn’t know what we were waiting for, but it was certainly not this: these days of dismal work, these silent evenings, this frozen life, without change, without surprise without hope.

Materially speaking, we are a little better off than before. We have two rooms instead of one. We have enough coal and sufficient amounts of food. But compared to what we have lost, we are paying too high a price.

On the bus in the morning, the ticket-taker sits down next to me. In the morning it is always the same one, fat and jovial. He talks to me for the whole ride. I don’t understand him very well; I understand nevertheless that he wants to reassure me by explaining that the Swiss will never allow the Russians to enter the country. He says that I must not be afraid any longer, that I must no longer be sad, that now I am safe. I smile. I can’t tell him that I’m not afraid of the Russians, and that if I’m sad, it’s more because I’m too safe at present, and because there is nothing else to do or to think about than the job, the factory, the shopping, the laundry, the meals, and nothing else to wait for but Sundays when I can sleep and dream a little longer about my country.

How can I explain to him, without hurting his feelings, and with the few French words I know, that his beautiful country is a desert for us, the refugees, a desert we must cross in order to arrive at what is called “integration,” “assimilation.” At that time, I don’t yet know that some of us will never arrive.

Two of our number returned to Hungary despite the prison sentence that awaited them. Two others, young bachelors, went farther, to the United States, to Canada. Four others went even farther, as far as one can go, beyond the great boundary. These four people of my acquaintance killed themselves during the first two years of our exile. One with barbiturates, one with gas, and two others with the rope. The youngest was eighteen. Her name was Gisèle.

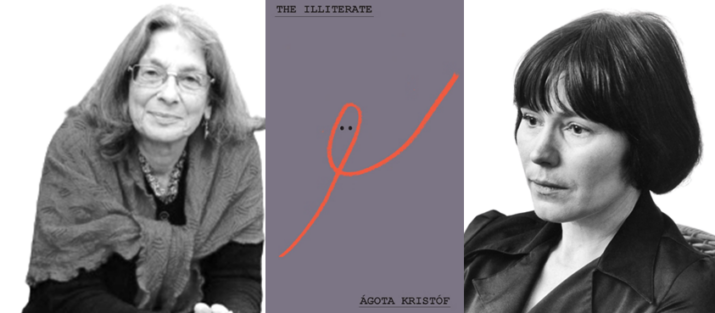

Ágota Kristóf was born in Csikvánd, Hungary, in 1935. Aged twenty-one, Kristóf and her husband and four-month-old daughter fled the Soviet repression of the Hungarian Uprising to Austria and were resettled in French-speaking Switzerland. Working in a factory, Kristóf slowly learned the language of her adopted country. Her first novel, The Notebook (1986), won the European Prize for French literature and was translated into forty languages. Kristóf’s other work included plays and stories as well as The Proof (1988) and The Third Lie (1991), which complete the trilogy begun with The Notebook. She died in 2011.

Nina Bogin was born in New York City and grew up on the north shore of Long Island. She attended Kirkland College (now Hamilton College) and received a BA from New York University. She has lived in France since 1976, has published three books of poetry, and has received a National Endowment for the Arts grant.

Excerpt from THE ILLITERATE, by Ágota Kristóf, translated by Nina Bogin. Copyright © 2004 by Editions Zoé. Translation copyright © 2014 by Nina Bogin. Reproduced by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Published on July 12, 2023.