Translated from the Italian by Hope Campbell Gustafson.

I can still remember the first time I saw the sea in Italy. We went without Papa—just me, Mama, and some friends. A walk along Ostia Lido after having visited Isola Sacra where the Tiber empties out, cloudy and dense. Her friends made fun of her because she was used to the ocean and thought that the tide could rise at any moment. “Don’t put your towel near the water, or the sea will take it away.”

“The sea,” they told her, “doesn’t come very far forward here.” It was spring: the beach deserted, no umbrellas. The sea was dirty, the sand too, but the smell of saltiness was enough to make her happy. She jumped up and down, did cartwheels. I ran after her and tried to catch her until, surprising everyone, Mama said that even though the water was cold, she was going in just the same. I saw her throw herself into the slimy sea, delirious with joy. When you’re a kid, everything seems immense.

“It’s dengelous!” I screamed from the water’s edge. I was scared, and I called out to her, flailing my arms. Every time she recalls this story, Mama starts to laugh.

“Can you believe it, you hardly knew how to talk!”

But she doesn’t tell the story about that last trip to Gezira with Papa. The new car, the music on the radio, her happily singing, and, out of nowhere, a garrison of pickups and frowning soldiers. Lined up on the right side of the road, the bodies of three men encrusted with sand. My eyes hardly reached the height of the window, yet they saw everything. My father stretched his arm back from the front seat to push my head down, then, turning to Mama, said: “Stay calm,” and got out of the car. Mama immediately moved into the back seat and pressed my face into her lap. Some very long minutes followed. My father got back in the car, said goodbye to the soldiers with a hand gesture, and began driving again, turning up the volume of the radio. The music, extremely loud at that point, drowned out my parents’ voices.

Just days later we would leave Somalia. It was the summer of 1990. That’s how we came to Rome, like many other Somalis in the months that followed.

When I ask my mother what happened to my father, she says that there’s been war in our country for fifteen years and as far as she knows he could be dead. She says it with a coldness that upsets me, so I immediately stop asking questions.

I think about my father often, about our first years together in Rome. It wasn’t uncommon for him to come get me at preschool. He’d carry me on his shoulders, and I liked seeing everything from above. His shirt would get a bit dirty from my little shoes, but it didn’t seem to bother him.

By that time Mama had already found a job and was trying to make new friends. Papa frequented a club. I don’t remember the neighborhood, but I’m guessing it was close to Termini. It was a sort of cellar, with an old, faded sign posted on the door. Whenever we walked in, there were always lots of men sitting around a table, and as soon as they saw my father, they would all stand up to greet him with reverence. One of them would make a gesture as if to take me into another room, but Papa opposed.

“I want him to stay here. Don’t worry. He’s a little man; he’ll behave himself,” he’d say, looking at me with pride. I felt important next to him, silently drinking a glass of aranciata and eating coconut cookies.

Back then I was a very good kid, even my mom says so: “When you were little, you were an angel!” as though being good depended on the presence of my father.

In that cellar, badly lit by neon lights, almost everyone smoked, and the ashtrays were always full of cigarette butts. Some chewed on little green leaves, but my father didn’t do either of those things—he didn’t smoke, he didn’t chew, he spoke with authority to those present and used difficult words, the kind that are hard for a kid to understand.

One night when we got home, my mom, hugging me, asked: “You smell like smoke. Where did he take you?”

I didn’t respond, even though Papa was watching TV and couldn’t hear us. It was supposed to be our secret. But later, while I was trying to fall asleep, I heard their voices coming from the living room: “You’ve kept me from participating in the liberation of our people! Let me go! There are still loyalists to the dictator—we have to annihilate them.”

“War is not the answer. You have to stay with us, we’re your family.”

I didn’t understand who the people he had to liberate were or even what annihilating someone means. Inside, I only hoped that Papa wouldn’t leave and that he’d stay with us forever.

It’s been many years since I’ve seen him. In the country where I was born, there’s the civil war, and one day my father left us to go fight. He pulled on khaki pants and camouflage combat boots and put himself in command of an army, and the soldiers agreed to obey him, so long as he’d restore order for all.

The wise men didn’t know how to get rid of the cruel beasts, so the people turned to two powerful magicians and rivals, Abow and Saykayeele.

“Do something!” they begged them. “Frightening monsters live in the river that Xiltir and Goole brought us.”

Abow went to an enormous garas tree and, after having lifted it from the ground with a spell, commanded:

“Go to the river, and crush all the crocodiles!”

Saykayeele went to a giant anthill and, after having lifted it from the ground, commanded: “Go and destroy all the crocodiles!”

The people waited along the riverbank to be freed from the terror, but when they saw the two magicians being followed by the tree and the giant anthill, they were even more frightened. The people feared the two new creatures more than they did the crocodiles.

“The garas tree and the anthill are much more dangerous than the beasts of the river,” said Yabar, a man who knew how to speak to animals. “We’d better ask the magicians to interrupt their magic.”

“Then who will protect you from those terrible animals? Remember that you were the ones to ask for our help!” the magicians admonished the people.

“I’ll help you live alongside the crocodiles,” Yabar offered himself, “whenever I am asked.”

The people joyfully accepted his proposal, and Yabar was elected commander of the river and of all its creatures: his duty was to protect the people and livestock from the crocodiles. The two magicians accepted the villagers’ wish, entrusted the two monsters to the commander, and gave the crocodiles an order: “From now on, you’ll obey Yabar, otherwise you’ll all be destroyed by the garas tree and the anthill.” The crocodiles agreed to obey Yabar and went back to swimming in the river.

“And if the magicians had refused to bend to the will of the people or, even worse, if they couldn’t stop the monsters, what would’ve happened to the river, the people, the crocodiles?” I ask.

Zia Rosa responds slowly. She seems to be searching for the most appropriate words while speaking: “If disproportionate, sometimes remedies are worse than evil.”

“But are we sure that the crocodiles will obey Yabar, like the magicians instructed them to? And will he manage, if necessary, to frighten them with the garas tree and the anthill?”

“We must be very wise to exercise the power that is bestowed upon us. The crocodiles are a necessary evil, yet the river people can’t live without water, so they elected the commander to help them govern it.”

“Were the wise men and the magicians the ones to nominate the commander of the river, or was it all the people together?”

“The commander of the river proposed himself: ‘I’ll protect you from the crocodiles; elect me,’ he said, and the people elected him because they believed his words. Yabar knows medicinal herbs and spells, he knows how to charm the crocodiles and get them to obey him, and he doesn’t act in his own interest, but in that of the people.”

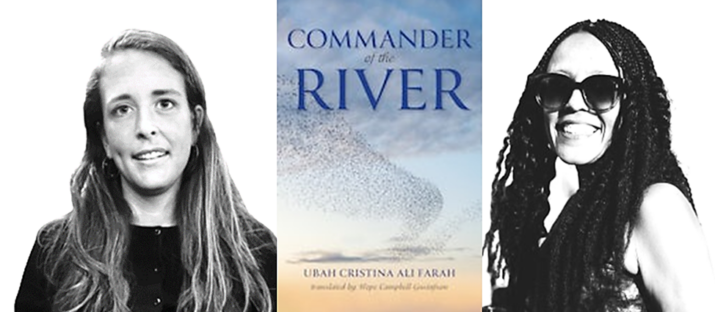

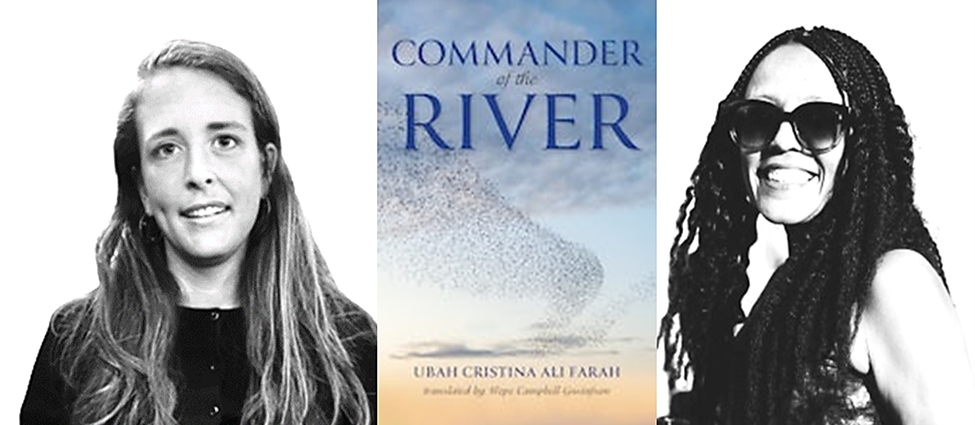

Ubah Cristina Ali Farah is a writer, poet, playwright, and performer of Somali and Italian descent. She was raised in Mogadishu, Somalia, but fled in 1991 at the outbreak of civil war, and eventually settled in Rome to teach Somali language and culture at Roma Tre University. Her stories and poems have appeared in several anthologies and her 2007 novel Madre piccola was awarded the prestigious Vittorini Prize. In 2006, she was awarded the Lingua Madre National Literary Prize.

Hope Campbell Gustafson has an MFA in literary translation from the University of Iowa and a BA from Wesleyan University. Her translation work can be found in various journals, in Islands—New Islands: A Vagabond Guide to Rome(Fontanella Press), and in Ubah Cristina Ali Farah’s Commander of the River (Indiana University Press, 2023), for which Campbell Gustafson received a PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant. From Minneapolis, now living in Brooklyn, Campbell Gustafson is Senior Program Associate for the Civitella Ranieri Foundation.

This excerpt from COMMANDER OF THE RIVER was published by permission of Indiana University Press. All rights reserved.

Published on July 12, 2023.