This is part of our special feature, Business in Politics and Society.

The debates about populism and neoliberalism have produced two disjointed discourses in the social sciences. The conventional approach to populism followed by most economists and political scientists has characterized it as a threat to the neoliberal order and a cultural backlash (Norris and Inglehart 2019) against cosmopolitan globalization. It describes populist leaders as opposed to business elites and liberal economic principles (Dornbusch and Edwards 1990). Businesses are, in turn, frequently hypothesized to oppose populism. When populists get elected, they are described as reckless political entrepreneurs openly breaking with liberal norms and erecting populist regimes imbued with state capitalism. In short, the conventional approach to populism hypothesizes that populist politics leads to a clash with most businesses and a divergence from liberal capitalism. In contrast to the conventional approach to populism, neoliberalism scholars (mostly sociologists, historians, and social anthropologists) have been more skeptical about the supposed clash between right-wing, nationalist populism, and neoliberalism. In a path-breaking piece of research on Alberto Fujimori’s Peru, Kurt Weyland has shown that populism and neoliberalism can cohabit comfortably (Weyland 1999). In another crucial paper, Adam Harmes has distinguished between internationalism and neoliberalism (Harmes 2012). While internationalists embrace all forms of global political cooperation, neoliberals oppose forms of political globalization that would entail a new set of international institutions curtailing capital accumulation. Thus, as Harmes concludes, neoliberalism can depend on nationalist policies if they enhance capital accumulation.

Right-wing populism has emerged within neoliberalism in Germany and Austria, not in opposition to it (Slobodian 2018). Several key supporters of Brexit have also argued for a return to the British state not to challenge neoliberalism but to shield it from European regulation and embark on a new export-oriented neoliberal trajectory (Wood and Ausserladscheider 2020). According to this emerging consensus amongst neoliberalism scholars, in many cases, right-wing populism is not a wholesale rejection of neoliberalism but only a variety of it. This new version remains within the neoliberal framework, amounting to a “mutation of neoliberalism” (Callison and Manfredi 2020). In contrast to the conventional approach to populism, this emerging neoliberalism literature also implies that some businesses support right-wing populists (Slobodian 2021). Thus, the two views, two academic discourses separated by disciplinary walls, could be hardly more different.

In my recent article published in Socio-Economic Review (Scheiring 2022), I enter this debate by presenting a framework to analyze the national populist mutation of neoliberalism in dependent economies. Following theory-testing process tracing, I substantiate this theoretical framework through a detailed mixed-method study of the strategic test case of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary. Utilizing new empirical material on businesses and policymakers, I show how the polarization of the business class rooted in global dependency structures, in interaction with a rising group of nationalist technocrats, has contributed to the national-populist mutation of neoliberalism. National-populist neoliberalism entails a new power bloc and a new compromise between national and transnational capital. It has preserved the core tenets of neoliberalism while modifying some of its peripheral elements and cutting back on avant-garde excesses to ensure the political viability of neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism meets national-populism

Neoliberalism has three faces: an intellectual-professional project, a repertoire of policies, and a form of politics (Mudge 2008). As a form of politics, neoliberalism is against the types of capitalism that put temporary shackles on capital accumulation in the name of popular pressures or national development goals. In response to these models, neoliberalism does not dismantle the state but builds new state institutions to improve accumulation conditions. Market-fundamentalism should not be confused with the “proto-neoliberalism” of Hayek, who was critical of laissez-faire and saw much room for an interventionist state. Market-fundamentalism also differs from the “rollout” phase of neoliberalism in the 1990s and 2000s, a period when neoliberalism relied on active state-building and regulatory reform to constitute markets and protect them from democratic intervention (Peck and Tickell 2002).

Close to neoliberalism as a form of politics, I regard neoliberalism as an accumulation strategy. As suggested by Bob Jessop, “an ‘accumulation strategy’ defines a specific economic ‘growth model’ complete with its various extra-economic preconditions” (Jessop 1991). Such accumulation strategies represent temporarily stable formations of the capitalist circuit, where various factions of the business class are conjoined, usually under the leadership of a dominant faction. In core capitalist countries, the Keynesian social-democratic configuration was the accumulation strategy of the post-war era. At the same time, import-substitution developmentalism—including state socialism—was the accumulation strategy in semi-peripheral countries. Neoliberalism emerged as the alternative to these strategies.

Following Aldo Madariaga (2020) and Cornel Ban (2016), I differentiate the core tenets of neoliberalism from its peripheral aspects. Peripheral institutions can change without jeopardizing core institutions. This distinction is crucial for “neoliberal resilience,” a process whereby neoliberalism dynamically adapts to external shocks to ensure its survival. The resilience of neoliberalism depends on the ability of dominant social groups to “defend those aspects of a neoliberal policy regime that—in their view—better serve their interests while allowing degrees of freedom in those aspects that they view as less relevant” (Amable and Palombarini 2009). According to Cornel Ban, at the core of neoliberalism are institutions designed to serve three primary goals: 1) credibility with financial markets, 2) trade and financial openness, and 3) competitiveness (Ban 2016). Neoliberalism is constantly evolving, negotiated by local actors filtered through domestic power struggles and ideologies, relying on different instruments to secure popular legitimacy, leading to different hybrids. However, as long as politics adheres to these core institutions, the accumulation strategy remains neoliberal.

In the real world, neoliberalism as an accumulation strategy and as a form of politics never presents itself as a pure ideology, or a set of internally coherent policies. It is embedded in social relations. Neoliberalism must ensure its political survival by forging coalitions that carry neoliberalism through the forest of governance. Neoliberalism must meet the needs of these social coalitions. Furthermore, in democratic societies, neoliberalism must secure an electoral majority to survive. Reagan and Thatcher relied on moral panics and a revival of traditional values to legitimate neoliberalism. Blair and Clinton fetishized globalism, and the spread of liberal democracy, while shifting some resources back to redistribution and human capital development to smooth the tensions inherent to neoliberalism. Some of these political instruments are at odds with economic textbook definitions of pure neoliberalism. Nevertheless, all these versions of neoliberalism remained committed to ensuring credibility with financial markets, trade and financial openness, and international competitiveness. The political instruments used to build social coalitions and to secure an electoral majority did not lead to a fundamental change in the accumulation strategy; there was no reversal back to Keynesian social democracy or a shift to a new alternative economic model.

Combining Weyland’s notion of “neoliberal populism” and Harmes’s notion of “neoliberal nationalism,” I regard national-populism as a “legitimation strategy” that can contribute to the political sustainability of neoliberalism. Populism as a legitimation strategy appeals to a mass public using a Manichean logic that opposes the virtuous people to corrupt elites and affiliated out-groups (Gidron and Bonikowski 2013). National-populist neoliberalism is thus a compromise between the core of neoliberalism and the political imperatives of advancing national interests, relying on populism as a legitimation strategy. National-populist neoliberalism emerged as an alternative to globalist neoliberalism. Globalist neoliberalism corresponds to what Nancy Fraser called ‘progressive neoliberalism’ (Fraser 2017) in core countries and what Dorothee Bohle and Béla Greskovits labeled ‘embedded neoliberalism’ (Bohle and Greskovits 2012) in the foreign-investment-dependent economies of Central Europe. Globalist neoliberalism differs from the radical neoliberalism exemplified by Chile or the Baltic states in dependent semi-peripheral countries (Madariaga 2020) or the early “roll back” phase of neoliberalism in core countries, which relied on an authoritarian-conservative populist legitimation strategy opposed to later progressive globalism (Hall 1985)

The mutation of neoliberalism in dependent economies

In semi-peripheral, dependent economies, such as Hungary, or most countries in Latin America and Europe’s eastern periphery, the business class is polarized based on access to international markets and technology. Compared to transnational capitalists, national capitalists have less access to the most successful sectors of the global economy. Therefore, the national bourgeoisie of peripheral states is structurally prone to rely directly on its political connections to compete with transnational companies. However, transnational capital must also compromise with domestic political and economic elites to secure the conditions of accumulation. Economic crises act as historical contingencies that throw the class compromise between the segments of the power bloc into question, thus jeopardizing the hegemony of neoliberalism. In these situations, elites need to reach a new consensus and reconstitute the power bloc. The balance of power determines whether the response to these crises leads to a new accumulation strategy or a modification of peripheral aspects of the prevailing accumulation strategy.

If the national capitalist class is strong enough to mobilize but weak to dominate transnational capital, and if populists can mobilize disillusionment with neoliberalism, then the resolution of the crisis of the neoliberal accumulation strategy will be the national-populist mutation of neoliberalism. In Hungary specifically, globalist neoliberalism was an accumulation strategy maintained by the class compromise of transnational corporations (TNCs), technocrats, and politicians. It institutionalized industrial policy based on economic openness and a strict preference for transnational capital. Taxation became increasingly less progressive, with a race to the bottom on corporate tax. Globalist neoliberalism also relied on redistribution to pacify the victims of neoliberalism, which led to a combination of austerity to maintain fiscal balance and recurring deficits and cycles of indebtedness. Discursively, globalist neoliberalism offered economic modernization, a cosmopolitan ideology of human rights, democratization, and European integration as a source of mass legitimation. It also attempted to depoliticize economic questions to prevent the political mobilization of economic anger.

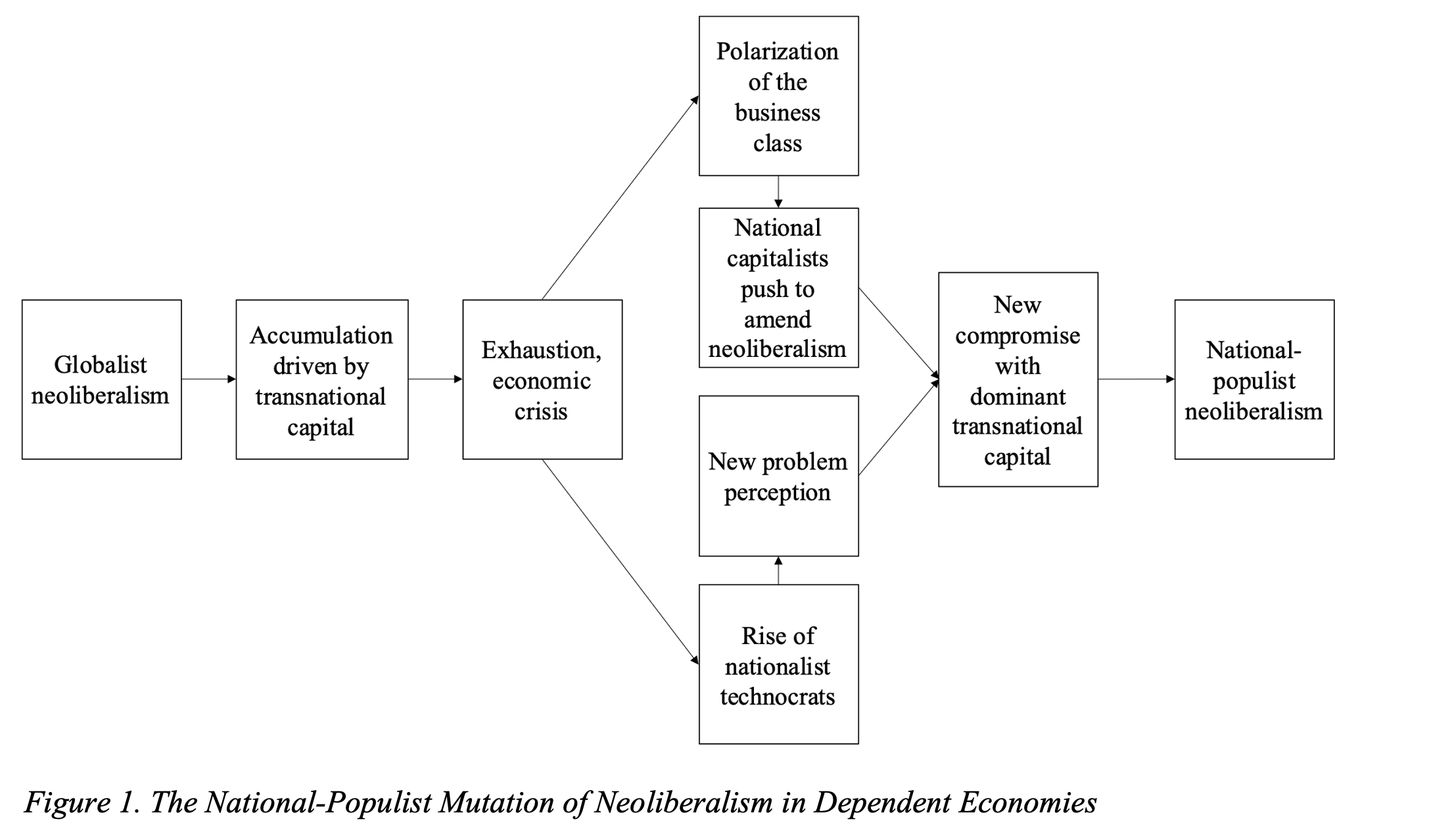

The exhaustion of this globalist neoliberal accumulation strategy in the 2000s led to the polarization of the business class and the growing influence of nationalist technocrats. Facilitated by national-populist politicians, national capitalists reached a new compromise with transnational capital, retaining the core aspects of neoliberalism. Figure 1 presents a summary of this process.

Viktor Orbán, the nationalist champion of business elites

In my Socio-Economic Review article, I follow a mixed-method approach relying on three primary data sources to demonstrate the national-populist mutation of neoliberalism in Hungary. The first dataset comprises data on the political connections of Hungarian capitalists encompassing the 2002–2018 period, including 222 individuals from publicly available publications about the 100 wealthiest businesspersons. I identified the main factions of the national capitalist class based on the role of political capital in their capital accumulation. Second, I also analyzed the press coverage of national capitalists and business advocacy organizations representing domestic and transnational businesses, covering 1990 to 2014 (more than 3600 printed pages). I use these data to analyze the political implications of the polarization of national and transnational capital, identifying which groups of the national capitalist class pushed for the amendment of globalist neoliberalism. Third, to analyze how policymakers channel business interests into the policymaking process, I collected data on 194 policymakers with economic portfolios (ministers and secretaries of state), covering 1990–2014. I identified left-liberal and right-wing policymakers and analyzed their embeddedness in the transnational or domestic economic sectors. Technocrats are policymakers with significant ties to the business class, deriving their legitimacy from ‘expertise’. I fit logistic regression to identify the odds of ever having been employed in a TNC among left-liberal and right-wing policymakers. I extend this quantitative analysis with a qualitative overview of the most critical policies in the four fields. Finally, I also analyze policy outcomes relying on international macro-data presented.

The results emerging from this empirical analysis show that a large segment of businesses supports Orbán’s populist regime. The severe dependence on foreign investment galvanized national capitalists and nationalist technocrats to support populists in amending globalist neoliberalism. However, they were too weak to challenge the dominance of transnational capitalists occupying the commanding posts of the economy. Therefore, manufacturing TNCs remained central to the power bloc and are among the biggest winners of Orbán’s populist regime. In other cases, such as Poland or Argentina, national capitalists were stronger and could push for more thorough developmentalist interventions that amounted to a stronger break with neoliberalism. In short, the balance of power within the business class matters for how the crisis of neoliberalism is resolved. Followers of the conventional approach to populism need to relax their politics-centered focus and pay more attention to business elite support for populists.

Orbán’s regime is a mutated continuation of neoliberalism, not a switch to developmentalism. Economic nationalism led to significant changes in the ownership structure of service sectors, including info-communications, mining, and finance. However, foreign investors retained their dominant position in technologically-intensive, export-oriented manufacturing and continue to dominate Hungary’s accumulation strategy. Embracing economic nationalism in industrial policy did not challenge the core of neoliberalism. Fiscal policy and social and labor market policy became even more neoliberal. The sphere of finance experienced the most momentous change. However, these moves either only remedied radical excesses of “avant-garde” neoliberalism (Appel and Orenstein 2018), such as pension privatization or foreign currency loans, or did not significantly diverge from the global shift towards more heterodox monetary policy after the 2008 crisis. Overall, fiscal policy remained conservative, and international financial credibility has improved since 2012. Despite noisy nationalism, these policy changes have not reached a threshold for developmentalism in practice. Research needs to pay more attention to the co-optation of economic nationalist goals into neoliberal strategies.

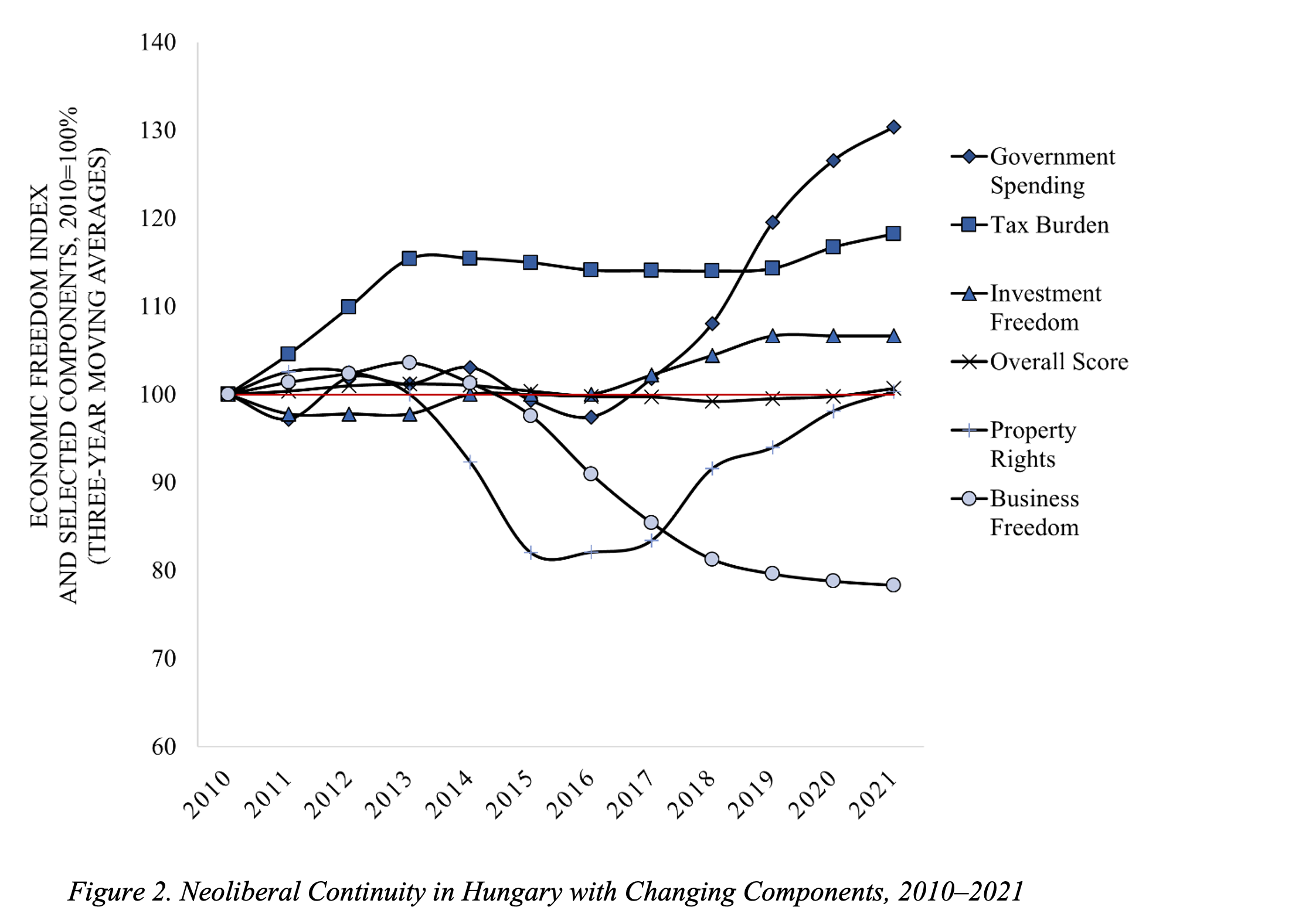

The Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, a widely accepted measure of neoliberal policies compiled by a leading neoliberal think-tank, supports the argument of neoliberal resilience in Hungary. With Orbán in power, the Heritage Index of Economic Freedom has remained stable, fluctuating around its 2010 value, as Figure 2 shows. In 2021, it was 2% higher than it was in 2010. Some dimensions, such as government spending, taxation, or investment freedom, have become more neoliberal. Other dimensions, most notably business freedom, have become less neoliberal. According to the Heritage Foundation, property rights freedom declined until 2016 but climbed back to their 2010 value by 2021. However, neoliberalism is not the same today as it was in the 1990s and 2000s. Certain peripheral institutions could be abandoned; avant-garde excesses could be corrected without jeopardizing the core of the neoliberal project. This national-populist neoliberalism is a compromise between the core of neoliberalism and the political imperatives of advancing national interests, relying on populism as a legitimation strategy. While economic nationalism serves to pacify and incorporate national capitalists, populism works as a legitimation strategy that systematically draws a large segment of the population into the orbit of the governing party. Populist campaigns against migrants and cosmopolitanism are designed to appease even those segments of society that are relative victims of Orbán’s polarizing policies by reframing distributive conflicts as issues of identity politics.

Neoliberalism has been mutating, not just in Hungary but in several key dependent economies such as the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte and Brazil under President Jair Bolsonaro, as well as in the “core of core” countries, such as the UK during Boris Johnson’s tenure and the US during Donald Trump’s. Local idiosyncrasies shape the various mutations of neoliberalism, but there are common underlying factors in contemporary capitalism pushing countries toward national-populist neoliberalism. Neglecting the embeddedness of populism in the business class and its compatibility with neoliberalism leads to a misunderstanding concerning the roots of the current populist wave.

Gabor Scheiring (PhD, Cambridge) is a Marie Curie Fellow at Bocconi University. His research uses quantitative, qualitative, and comparative methods to address the socio-economic determinants of inequality in health and wellbeing and how these inequalities shape democracy and capitalist diversity through the national-populist mutation of neoliberalism. His book, The Retreat of Liberal Democracy (Palgrave, 2020), winner of the BASEES 2021 Book Award, shows how working-class dislocation and business elite polarization enable illiberalism in Hungary. His work has appeared in leading journals such as The Lancet Global Health, Socio-Economic Review, Theory and Society, and the Annual Review of Sociology.

References

Adam Harmes, “The Rise of Neoliberal Nationalism,” Review of International Political Economy 19, no. 1 (2012), 59.

Aldo Madariaga, Neoliberal Resilience: Lessons in Democracy and Development from Latin America and Eastern Europe (Princeton 2020: Princeton University Press).

Bob Jessop, “Accumulation Strategies, State Forms, and Hegemonic Projects,” in The State Debate, ed. Simon Clarke (Houndmills, Basingstoke 1991: Palgrave), 161.

Bruno Amable and Stefano Palombarini, “A Neorealist Approach to Institutional Change and the Diversity of Capitalism,” Socio-Economic Review 7, no. 1 (2009), 640.

Cornel Ban, Ruling Ideas: How Global Neoliberalism Goes Local (Oxford 2016: Oxford University Press).

Dorothee Bohle and Béla Greskovits, Capitalist Diversity on Europe’s Periphery (New York 2012: Cornell University Press).

Hilary Appel and Mitchell Orenstein, From Triumph to Crisis: Neoliberal Economic Reform in Post-Communist Countries (Cambridge 2018: Cambridge University Press).

James D. G. Wood and Valentina Ausserladscheider, “Populism, Brexit, and the Manufactured Crisis of British Neoliberalism,” Review of International Political Economy Published online, no. 03 (2020).

Jamie Peck and Adam Tickell, “Neoliberalizing Space,” Antipode 34, no. 3 (2002), 384.

Kurt Weyland, “Neoliberal Populism in Latin America and Eastern Europe,” Comparative Politics 31, no. 4 (1999).

Nancy Fraser, “From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump—and Beyond,” American Affairs 1, no. 4 (2017).

Noam Gidron and Bart Bonikowski, Varieties of Populism: Literature Review and Research Agenda, 2013, Working Paper Series, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University, No.13-0004., Cambridge, M.A.

Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart, Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism (Cambridge 2019: Cambridge University Press).

Quinn Slobodian, “The Backlash Against Neoliberal Globalization from Above: Elite Origins of the Crisis of the New Constitutionalism,” Theory, Culture & Society Published online (2021).

Quinn Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Cambridge, MA 2018: Harvard University Press).

Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards, “Macroeconomic Populism,” Journal of Development Economics 32, no. 2 (1990).

Scheiring, Gábor (2022), “The National-Populist Mutation of Neoliberalism in Dependent Economies: The Case of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary,” Socio-Economic Review, Advance access, published on Feb 15, 2022.

Stephanie L Mudge, “What is Neo-liberalism?” Socio-Economic Review 6, no. 4 (2008), 704.

Stuart Hall, “Authoritarian Populism: A Reply,” New Left Review, no. 151 (1985).

William Callison and Zachary Manfredi (eds.), Mutant Neoliberalism: Market Rule and Political Rupture (New York 2020: Fordham University Press).

Published on November 2, 2022.