This is part of our new Campus series, Teaching Genocide.

This is part of our new Campus series, Teaching Genocide.

The January 10, 2022 decision by the McMinn County Board of Education in Tennessee to prohibit the teaching of Art Spiegelman’s graphic memoir Maus from its eighth grade (typically, thirteen-year-old students) curriculum set off a firestorm of media attention. The elected school board—which, as typical for the United States, holds significant authority over what is taught in classrooms—made its unanimous decision on the basis of members’ stated objections over “foul language” and depictions of nudity in the work.[1] Almost immediately, the decision to ban the book sparked controversy and was covered widely in the mainstream press and social media, with many commentators reading more into the decision than prudishness, and decrying the decision as engaging in Holocaust denial, antisemitism, and censorship.[2]The severity of the response to the decision—which included skyrocketing sales for the book on the one hand and many defenses of the school board’s actions on the other—points to deepening fissures that are taking place in school districts and state legislatures around the US over teaching histories of racial violence and oppression.

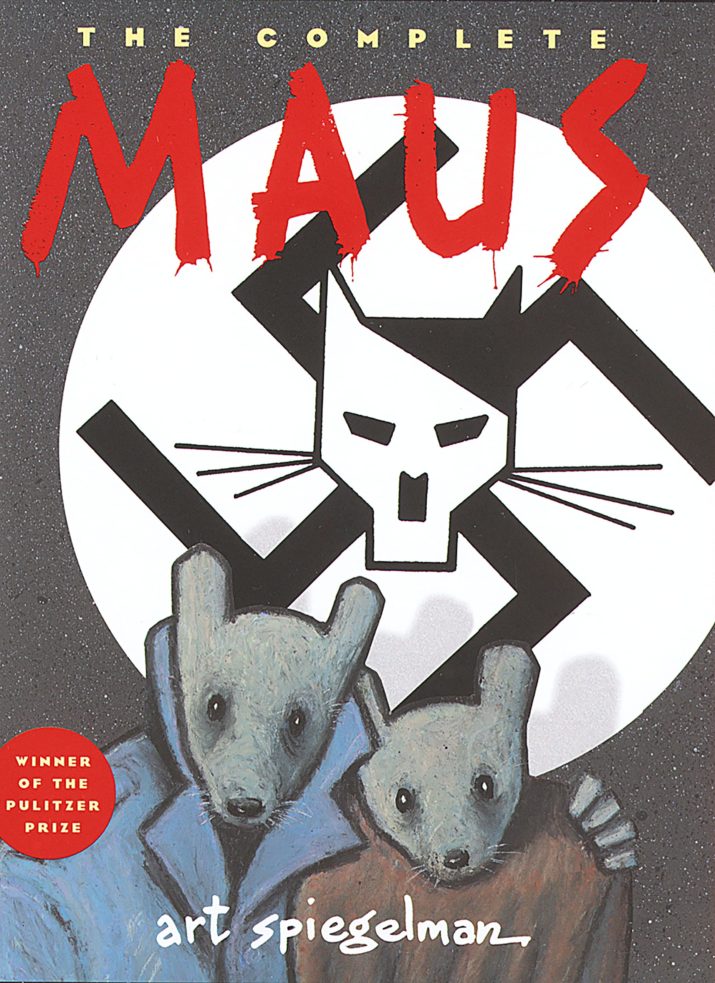

When Volume I of Maus (“My Father Bleeds History”) first appeared in book form in 1986, it was met with a mixture of enthusiasm and criticism. It tells the harrowing experience of the author’s parents, Vladek and Anja (née Zylberberg) Spiegelman, as Polish Jews in the Nazi Holocaust. It is also a compelling account of the author’s own struggles to contend with generational trauma and the weight of his parents’ memories and loss, including the death of his brother Richieu in the Holocaust, and his mother’s eventual suicide. It is a gripping tale that is, in turn, extraordinarily moving, visually engaging, and deeply introspective. Part of the attraction of the work—as well as a source of early debate—is that its characters are drawn as animals and arranged in an occasionally inconsistent schema that depicts different races and/or nations as various species.[3] Jews are mice, Germans are cats, Poles are pigs, and so on. The use of animals to illustrate the various characters in the work initially raised questions regarding the biological determinism of the work, as well as objections to the depiction of Jews as rodents (an antisemitic trope) and concerns over whether it was appropriate to represent the seriousness of the Holocaust through the medium of comic books. Despite these criticisms, the work continued to gain attention for its minimalist style, its effective weaving of contemporary and historical timelines, and the author-as-narrator’s own relentless self-reflexivity concerning his artistic choices. By the time Volume II (“And Here My Troubles Began”) appeared in 1991, Maus was widely hailed a genre-defining masterpiece. It won the Pulitzer Prize the following year and became the subject of museum exhibitions, journalistic features, scholarly studies, reprints, and special editions. It played a central role in the widespread legitimization of graphic novels as a genre of serious literature. It has been translated into over thirty languages. Now a canonical text of Holocaust memory and autobiography, Maus has been regularly taught in middle, high schools, and universities in the US.

The recent banning of Maus in Tennessee schools occurred amidst a protracted period of public debate over how and whether to teach America’s history and continuing legacies of racial violence, a debate which itself is symptomatic of a larger moment of partisan divide in the country. Much of the dispute over school curricula has been over the teaching of “critical race theory” (CRT), a scholarly approach to researching and identifying systematic racism in the country’s legal, educational, economic, political, and carceral institutions. Discussions of CRT date at least to the early 2000s, but it gained widespread attention following the publication of The 1619 Project, a 2019 collaborative journalistic work directed by New York Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones. The 1619 Project presents a powerful challenge to the traditional “Founding Fathers” narrative by placing the institution of slavery, the persistence of racism, and the contributions of African Americans at the center of United States history. It was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2020, and immediately became a flash point for debates around CRT.

Since the publication of The 1619 Project, at least twelve US states have passed laws that prohibit CRT from being taught in public schools. These laws prevent teachers from teaching the present-day impact of historically racist laws and discriminatory practices on people of color, or from discussing how white Americans have benefitted from them. Texas House Bill 3979, which was passed in July 2021 and enacted in December of that year, is representative of this legislation. Among other restrictions, it prohibits teachers from teaching that:

an individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex;

an individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of the individual’s race or sex;

meritocracy or traits such as a hard work ethic are racist or sexist or were created by members of a particular race to oppress members of another race;

the advent of slavery in the territory that is now the United States constituted the true founding of the United States; or

with respect to their relationship to American values, slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.[4]

The passing of Texas’s HB 3979 led one school administrator to warn teachers to “make sure that if you have a book on the Holocaust, that you have one that has an opposing, that has other perspectives,” a statement that brought widespread condemnation.[5]

Although the Tennessee school board’s discussion of Maus did not make explicit reference to CRT, it occurred during a new wave of fights over books taught in schools that contain references to slavery, racism, LBGTQ+ persons, or sexually suggestive material, according to the American Library Association, which maintains a list of the most frequently banned and challenged books in public schools and libraries.[6]

Such fights have been occurring in many states, as in the 2021 successful Virginia gubernatorial campaign of Republican Glenn Youngkin, which focused on the supposed danger of teaching Toni Morrison’s award-winning novel Beloved. Although the work is widely taught for its portrayal of the extreme violence that was inherent to American slavery, it was criticized by Youngkin for being “sexually explicit.”[7] Since attaining office, Youngkin has banned educational policies that encourage diversity and established a telephone “tip line” where students and parents can report their teachers who raise topics that might be considered “divisive.”[8] Not to be outdone, the Florida legislature has recently passed a “Don’t Say Gay” bill, which prohibits “classroom discussion about sexual orientation or gender identity” in lower school grades and requires teachers to inform parents when their students disclose their sexual orientation.

What made the Tennessee school board’s decision so surprising was that up until then, discussions of the Holocaust had largely been immune to these debates. By 2015, thirty-five states and the District of Columbia had mandated teaching of the Holocaust in public schools and Holocaust education had been promoted by educational organizations around the country. The scholar Thomas Fallace has shown that although the Holocaust was taught in the 1960s and 1970s as part of a movement toward progressive education, it began to be mainstreamed in the 1980s, reflecting a widening popular understanding of the event.[9] The motivations for these educational directives have varied. At times, it has been invoked to teach the specific history of antisemitism and to counter anti-Jewish activity, such as in the case of Illinois, when, a decade after pro-Nazi marches in the town of Skokie, the state enacted mandatory Holocaust education. At other times, the Holocaust has been taught to impart universal “lessons” of tolerance and the consequences of bigotry and discrimination. Some have also argued that Holocaust education has been a way for political figures to demonstrate their support for issues of concern to Jewish voters.[10]

What does it mean, therefore, to teach Maus in our contemporary moment of CRT-induced panic and racial reckoning? The outpouring of support for the work that appeared in the wake of the ban has only affirmed the graphic memoir’s position as a valued and authoritative resource. As of the writing of this article, no other school board has repeated the decision to forbid the teaching of the work in the US and it momentarily became the top seller on Amazon.com. Nevertheless, to teach Maus in the wake of the McMinn County Board of Education’s decision to ban it has become a political and not only a pedagogical act. It is an assertion of academic freedom. It is an expression of a commitment to teach historical subjects that are politically divisive and which have the potential to force the racial self-interrogation that opponents of CRT are trying to prevent.

Such a nation-wide reckoning has become ever more urgent. Over the past several years, Nazi and Confederate symbols have regularly appeared together in far-right political events, such as the murderous 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, the January 6, 2021 insurrection in the US capitol, and, in the late winter 2022, truckers’ protests in Ottawa, Canada. The consequence of this merging of symbols is that Nazism and the Confederacy are increasingly carrying equivalent historical and representative significance among white supremacists. Therefore, to teach the history of one compels a consideration of the other and demands a recognition that the two events intersect with one another historically, ideologically, intellectually, and politically. Indeed, some of the most innovative work in Holocaust Studies in recent years links the Holocaust to genocide more globally, to American histories of Black codes and racial violence, and to Western practices of colonialism, cultural genocide, and ethnic cleansing.[11]

Furthermore, for all of the purported concern over the portrayal of naked cartoon mice and the occasional profane word, Maus is not a work limited to European history. It too points to deep racial divisions within the United States. Its framing narrative is an autobiographical account of Art Spiegelman himself that takes place in post-war America, at a time when the perceived racial status of Ashkenazic Jews was undergoing a transformation. Increasing numbers of Jews of European ancestry were being accepted into, and benefitting from the privileges of, the white majority culture. This is present in the subtext of the opening scene of Volume I, which is set in Rego Park, NY, a community where Jews migrated after benefitting from federally-subsidized loans that allowed them to move out of crowded Manhattan neighborhoods, an opportunity that was systematically denied to Blacks.[12] It is present in Volume II, when Art’s wife, Françoise, stops to pick up a Black American hitchhiker (depicted as a black dog, with speech patterns that are more caricature than representative of Black American speech) and Vladek responds with a racist diatribe and panic over the perceived threat the hitchhiker poses. It is most apparent in Art’s questioning of his decision to employ animals as stand-ins for racial and national groups, and when he debates about how to depict the French-born Françoise, who converted to Judaism (and therefore would not have been targeted for extermination under Nazi laws that identified Jews as a racial group). Should she be a frog by virtue of the fact that she was born French or a mouse because of her conversion to Judaism?

To some observers, the focus of the Holocaust in United States’ schools, museums, memorial sites, university programs, and popular culture has been a strategy for teaching about hatred and oppression without having to engage in the national self-criticism that might result from interrogating America’s own history of racial violence and injustice. The geographic distance of the Holocaust has allowed most Americans to learn about it without having to engage in questions of historical responsibility. It even permits us to imagine that through our study we are engaging in an act of moral witnessing without having to be held directly accountable for its implications and repercussions.[13] Unsurprisingly, the strong support for Holocaust education and memory in the United States has prompted some scholars of African American history and advocates for racial justice to demand that the history of slavery and racism be at least as central to American education and memorial culture.[14] However, the McMinn County Board of Education’s decision to ban Maus has forcibly brought discussions of CRT, the experience of Black Americans, and the ongoing threat of white supremacy directly into the teaching of the Nazi Holocaust. It compels us to contend with the questions of race and racism that are present within the text itself and provides opportunities to recognize the intersectionality of the Nazi Holocaust and America’s racist past.

Barry Trachtenberg holds the Rubin Presidential Chair in Jewish History at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He is the author, most recently, of The Holocaust & the Exile of Yiddish: A History of the Algemeyne Entsiklopedye (Rutgers University Press, 2022).

References

[1] McMinn County Board of Education, Called Meeting, January 10, 2022. (https://core-docs.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/asset/uploaded_file/1818370/Called_Meeting_Minutes_1-10-22.pdf). Note: all weblinks were active as of March 22, 2022.

[2] See, for example, Luke Winkie, “Art Spielman on Maus and free speech: ‘Who’s the Snowflake Now?” The Guardian, February 5, 2022; and Sophie Kasakove, “The Fight Over ‘Maus’ Is Part of a Bigger Cultural Battle in Tennessee,” New York Times, March 4, 2020. A Google news search with the keywords “Maus” and “Tennessee” from January 10, 2022 to March 22, 2022 turned up more than 200 new stories in at least half a dozen languages.

[3] See, for example, the review by Harvey Pekar, “Maus and Other Topics,” The Comics Journal, December 1986: 54-57.

[4] Hughes, et al., Texas House Bill 3979, (https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/87R/billtext/pdf/HB03979F.pdf).

[5] Dani Anguiano, “Texas School Official says Classrooms with Books on Holocaust Must Offer ‘Opposing’ Views”,” The Guardian, October 15, 2021. I am grateful to Wake Forest University student Story Sinex for bringing this statement to my attention.

[6] American Library Association, “Top 10 Most Challenged Books Lists” (https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/top10).

[7] Aaron Navarro, “Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ at center of latest battle in Virginia governor’s Race,” CBS News, October 25, 2021.

[8] Hannah Natanson and Karina Elwood, “Virginia Education Department Rescinds Diversity, Equity Programs in Response to Youngkin’s Order,” Washington Post, February 25, 2022; and Gregory S. Schneider, “All 133 Virginia School Superintendents Urge Youngkin to Scrap Tip Line and Content Policy” Washington Post, March 11, 2022.

[9] Thomas D. Fallace, The Emergence of Holocaust Education in American Schools (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

[10] See the discussions in Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American Life (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), 258-261.

[11] See, for example, Danielle Christmas, “The Plantation-Auschwitz Tradition: Forced Labor and Free Markets in the Novels of William Styron.”Twentieth-Century Literature 1 (Spring 2015): 1-31; Dorota Glowacka, “‘Never Forget’: Indigenous Memory of the Genocide and the Holocaust,” in Holocaust Memory and Racism in the Postwar World, edited by Shirli Gilbert and Avril Alban (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2019), 237-258; A. Dirk Moses, The Problems of Genocide Permanent Security and the Language of Transgression (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021); Valentina Rozas-Krause, “Postcolonial Berlin: Reckoning with Traces of German Colonialism,” in Neocolonialism and Built Heritage Echoes of Empire in Africa, Asia, and Europe, edited by Daniel E. Coslett (New York Routledge, 2020), 65-84; and James Q. Whitman, Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

[12] K. Hinterland, M. Naidoo, L. King, V. Lewin, G. Myerson, B. Noumbissi B, M. Woodward, L.H. Gould, R.C. Gwynn, O. Barbot, and M.T. Bassett, Community Health Profiles 2018, Queens Community District 6: Rego Park and Forest Hills; 2018; 48 (59):1-20 (https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2018chp-qn6.pdf).

[13] See the discussions in Susan Neiman, Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2019) and Michael Rothberg, The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019).

[14] For example, see John J. Cummings, III, “The U.S. has 35,000 Museums. Why is only one about Slavery?” Washington Post, August 13, 2015.

Published on May 18, 2022.