Translated from the Spanish by Victor Meadowcroft and Anne McLean.

Mothers stay with their children during the first years, and then, when the children can — apparently — defend themselves, they release them, they cast them into the naked tumult, and forget them. I’ve seen mothers who despair at having to provide for their children, letting out huge yawns while contemplating them. I never knew if this was because they were racked by exhaustion and fatigue, or out of hunger, a cyclopean desire to devour their young. In any case, these are the same mothers who take responsibility for ex-plaining to them — with beatings, yelling, and gestures — the world into which they’ve arrived. Otherwise, the majority of us (and even our mothers themselves) would never have been able to survive. For my part, I don’t know which of all these women — who wander in circles throughout the house, and whose troubled eyes sometimes occupy the miniature abyss of my window — is my mother. It’s likely she’s still alive. As for my father, he could be a naked one, or a clothed one; in either case his absence is the same. I know, from the sporadic comments of one or other of the elders who remembers, that an old woman snatched me from my mother’s arms the moment I was born, and held me pressed tightly against her, my head between her breasts, my body sheltered beneath her hair, and she didn’t allow anyone to touch or look at me for years. In other words, she defended me from death until she herself died. And yet, according to these same offhand comments, I continued to behave as though the old woman were still alive, hiding from every-one and everything, fleeing even from their looks, from the trembling hands that were sometimes extended toward me; and when I was finally able to find my place inside my ward-robe, my respite, nobody could say they had ever seen me defenseless before the eyes of anyone, not a single time.

And so I grew. I don’t know if I have siblings. I don’t want to know. It makes no difference. In this house, we are all alone. In this house nobody can trace a direct link to their predecessors, dead or living; nobody knows where or how or why or whether their siblings, cousins, or grandparents still breathe. The old-timers almost never talk about them-selves, or about us, and when they do, they skirt nervously around each topic, always with an incredulous gaze straying toward the empty plates, as if awaiting anxiously — though with little hope — the weight and presence of more food.

When I tried to coax something about my past from the elders, I learned of nothing but the abduction and the old lady who defended me from death. And when I ventured to ask about the pasts of these same elders, about their lives — and as such about ourselves, about our past — it was useless, absurd; they confessed nothing because they know nothing, except that they themselves don’t ask about it either. They know only what we all know: that we appeared wandering among the naked tumult with two sexes (some more man than woman and others more woman than man), and that on the other side of the door only death awaits. Very occasionally, the elders talk among themselves in low voices, but they only say what other elders in other corners and at other times have always said. They recall the cemetery, for example, a favorite topic, the first tombstone, torture in the street, and then they go silent, chewing on invisible mouthfuls, to strengthen their jaws, I presume, to be able to devour more when the fleeting opportunity arrives, or perhaps to have an excuse to remain eternally silent, shrug-ging their shoulders. The oldest of the naked ones is a gruff, bald giant who invariably sits in the most hotly contested corner — next to one of the largest kitchens — from which he can grab a piece of something simply by extending one of his big hairy hands. He’s like a statue made of dark marble, covered by what is surely the longest and thickest beard that’s ever ex-isted in the entire history of this house. Occasionally, he’s approached by groups of visitors who set about enthusiastically examining him: first they move aside the long, ash gray train of his beard — which always rests between his stonelike legs — and observe him closely, with cries of jubi-lant panic, and then they stimulate him, rousing him with two or three sharp raps, as if knocking at a door (though the mere stupefaction of the clothed ones constitutes a stimu-lus for the old-timer). Next they measure him, weigh him, issuing unanimous exclamations; they slap the old man on the back, as if congratulating him, before carefully draw-ing his beard back across his most essential union, and finally they interrogate him, amid laughter, about his selfamorous encounters — never wishing to procreate, he has always withdrawn at the crucial moment; they encourage and investigate him, without ever disrespecting him, with-out ever unsettling him with a severe look, for it so hap-pens that this enormous bald elder is like a religion, the grandiose shell of what was once a titan, a colossal relic, peremptorily instituted by the clothed ones, a bountiful scrap heap who must be maintained and obeyed — an extraordinary pastime, the most naked of distractions, a savage celebration sometimes achieving miracles of happiness for the women with veiled faces, for as they themselves put it, this old man is our tender barbarity to enjoy, the most beautiful game of love that continues to live despite his age, a volcano, a beating heart, so they reward the old man with two or three plates of raw meat and bid him affectionate fare-wells, with more vigorous backslapping, as if encouraging him to remain alive until the next visit, the next necessity, the next use. He is protected, one of the few.

They call him Jesús.

And just like Jesús, the majority of old-timers can be found dispersed in the corners closest to the kitchens, all leaning against the walls, panting, as if attempting strategically to protect their backs — pink and slavering seals, huge, small, wrinkled, and hoarse. Damp, despicable seals. Seals and seals and more seals.

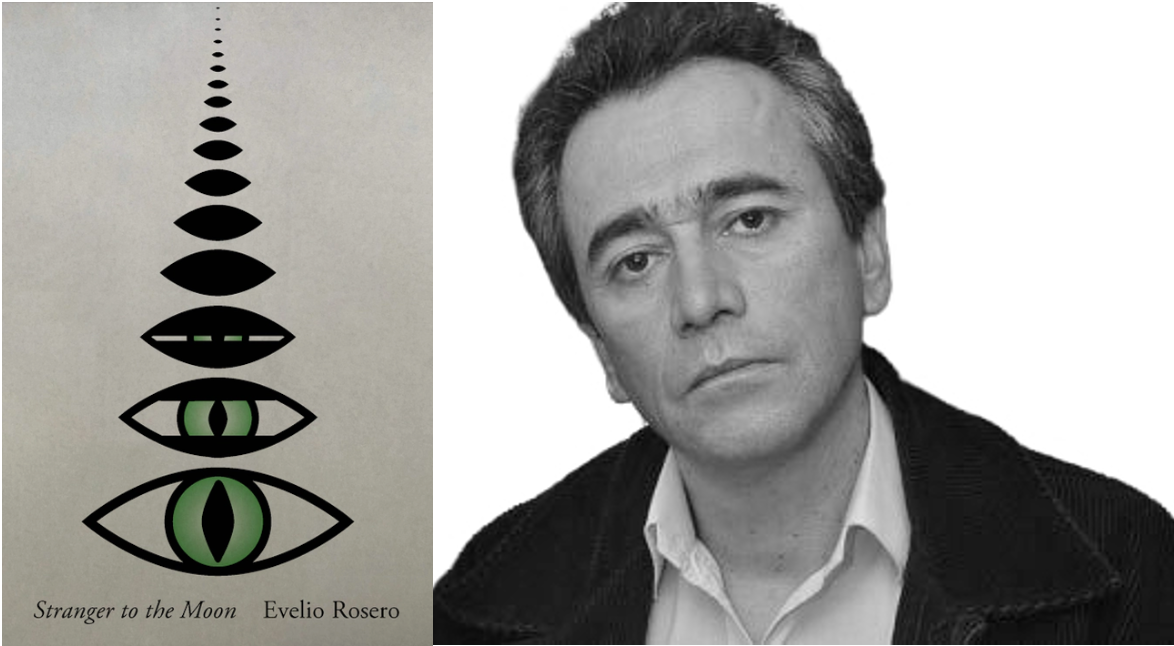

Evelio Rosero was born in Bogotá, Colombia, in 1958. He was awarded Colombia’s National Literature Prize by the Ministry of Culture in 2006 for his body of work, which includes several novels, short story collections, and books for young readers and children. The Armies, Rosero’s first novel to be translated into English, won the Tusquets International Prize and the 2009 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize.

Victor Meadowcroft lives in Brighton, England. He translates from the Spanish and Portuguese.

Anne McLean lives in Toronto and has translated the works of authors including Héctor Abad, Javier Cercas, Julio Cortázar, Evelio Rosero, and Juan Gabriel Vásquez.

This excerpt from Stranger to the Moon was published by permission of New Directions Publishing. Copyright © 1992 by Evelio Rosero Diago. Copyright © 2010 Random House Mondadori, S.A. Copyright © 2021 by Victor Meadowcroft and Anne McLean