Translated from the Bulgarian by Izidora Angel

Naya and I have been living together since we were born. First in the Home, then in the attic room we shared in the Reduta neighborhood. She was given up for adoption as a three-day-old baby. The story goes that her mother got pregnant at sixteen by some boy she never saw again. To avoid the public indignity of it all, her parents locked her up in their village house on the vineyard, like a prisoner of her own naiveté. Every few days for three months, her mother would come to bring her food and water and to check on her. But nobody was there when her contractions started; no one had imagined she’d go into labor in the seventh month. She would have had little use in banging on the door or screaming—the house was deep off the main road and out of earshot, and since it was right before Christmas, the other villagers were keeping warm inside their houses. Hours passed before her mother found her lying on the floor in a puddle of blood, a sleeping baby swaddled in her lap. They saved the baby’s life, but quickly got rid of it.

That’s the story of how Naya ended up in the Home. Her mother died a few days later. I picture her obituary reading something like this:

“Rest in peace, our dear child!

Your grief-stricken mother, father, and brother.”

Not a word about that other child, the one just barely tasting life but already vanishing in a haze of disremembrance.

Naya came into this world prematurely, unwanted, and marked for life by these events, which the Home’s Matrons made sure to recount to every adolescent girl as a cautionary tale. Naya’s real name is Nadezhda, meaning hope. It had been her dying mother’s attempt to bestow her with good fortune.

One Christmas, a big box of donations arrived for us at the Home. Clothes, toys, and sweets. We were elated, and jumped up and down for two hours. Sure enough, the Matrons ransacked every-thing. They kept the nicer clothes for their own kids or to give away as Christmas presents to relatives, and what remained they sold to the sales women at the department store, reaffirming that enduring, two-way relationship. Those same saleswomen then sold everything off-register for a percentage of the profit—even the youngest of us at the Home knew this.

To save face, it being Christmas and all, the Matrons allowed us some plain vanilla wafers called “Naya.” Our friend, still Nadya then, took such pleasure in devouring the crispy wafers that she insisted we call her Naya, too. We didn’t mind. Every time someone called out her name, the sweet taste of the wafers seeped into our conscious-ness and we munched away our Christmas memories. Na-ya, Na-ya.

One night, the boys broke into our sleeping ward. They were sixteen, seventeen, we were barely twelve. I knew what they wanted to do to us, I’d heard about it from the older girls. There was no point in screaming—еven if the only Matron on duty could hear us over her nine o’clock TV show, she wouldn’t have done anything about it. The Home was like an aquarium: the big fish ate the little fish, everyone saw it happen through the glass, and no one did anything to stop it. It happened again the following night, and the one after that. I squeezed my eyelids shut underneath the blanket just as I’d done when I was little and I tried to outrun my demons, but they caught up to me over and over again.

Naya turned out to be the savviest of us all. Soon the boys com-pletely stopped bothering her. One day during lunch she whispered to me how she did it. She shat herself. Revolted, they didn’t come anywhere near her. At twelve years old, Naya shat herself every single night, of her own volition, and with the outward calm of a Tibetan monk. She told me this in between bites of macaroni and feta. Now it was up to me to choose between these two evils. I chose to follow suit. And I finished my lunch.

Sometimes I’m asked what life in the Home had taught me. I used to go for an answer the person asking could actually take; something that rewarded them for caring. But lately, I’ve gone another way with it.

Stoycho was six when the ambulance took him away and we never saw him again. He had suffered broken ribs, a fractured skull, and a brain hemorrhage. He died a few days later. It all happened when we were making our way back down from the cemetery at the top of the hill. We snuck up there to snatch the food left at the gravestones in memory of the departed, God rest their souls. Usually we found the requisite plastic cups of boiled barley and powdered sugar, but some days we stumbled on plain biscuits and Turkish delight. Anything we came across we were ordered to bring back to the older kids. We weren’t allowed so much as a taste from what we salvaged. But we were ravenous, carrying food forbidden to our rumbling bellies, and we found it excruciating to resist. Those of us who secretly tasted the barley with powdered sugar and were lucky enough to get away with it relished the sweetness long into our dreams, but one of the kids saw Stoycho do it and squealed to the older kids. Squealing got you a biscuit. Stoycho was beaten like a dog while the Matrons stared blindly out the window until he was left lying in a puddle of his own blood. Someone did call an ambulance eventually, but at that point it was too late.

Stoycho had been a glutton by nature. Some of the kids said they saw him ducking in the bushes by the street at dusk, waiting for the goats to come home from grazing. They said he suckled one of the does. No one could figure out why the animal had allowed it.

What did life in the Home teach me? The only thing that mat-tered. Survival.

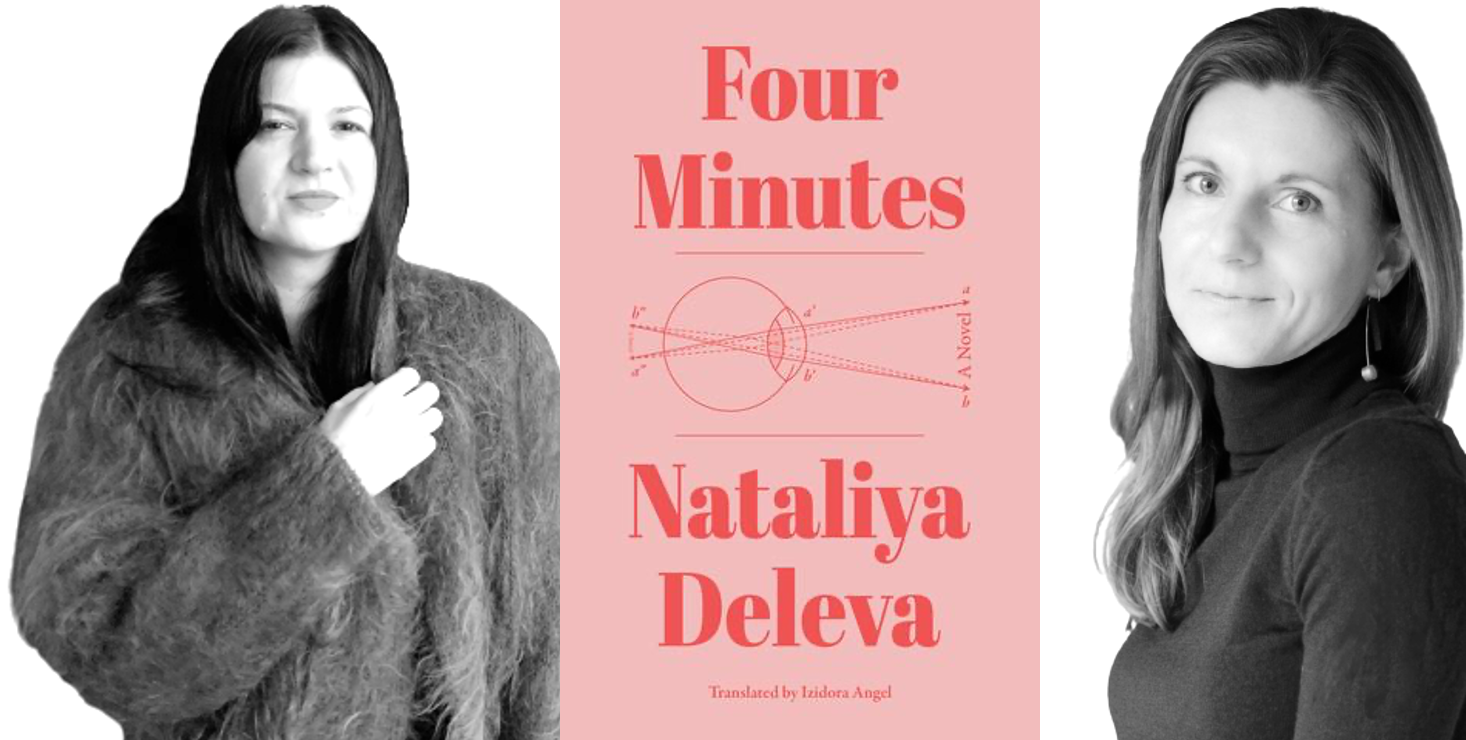

Nataliya Deleva is a Bulgarian-born writer living in London. Four Minutes is her debut novel. Originally published in Bulgaria (Janet 45, 2017), the book was awarded Best Debut Novel and was shortlisted for Novel of the Year (2018), and has since been translated into several languages, including German (eta Verlag, 2018) and Polish (Wydawnictwo EZOP, 2021). Nataliya’s short fiction, critique, and essays appeared in Words Without Borders, Fence, Asymptote, Empty Mirror and GrantaBulgaria, among others. Her second novel, Arrival—an English-language original—is forthcoming from The Indigo Press in 2022.

Izidora Angel is a Bulgarian-born writer, translator, and creative director living in Chicago. She has published essays, critique, and translations for the Chicago Reader, Publishing Perspectives, EuropeNow Journal, Drunken Boat (Anomaly), Banitza, Egoist, and others. She is a founding member of the Third Coast Translators Collective. Her debut translation of Hristo Karastoyanov’s The Same Night Awaits Us All (Open Letter, 2018), received an English PEN grant, an ART OMI fellowship, and was shortlisted for Peroto Literary Awards in 2018.

This excerpt from FOUR MINUTES was published by permission of Open Letter Books. Copyright © 2017 by Nataliya Deleva. Translation copyright © 2021 by Izidora Angel.