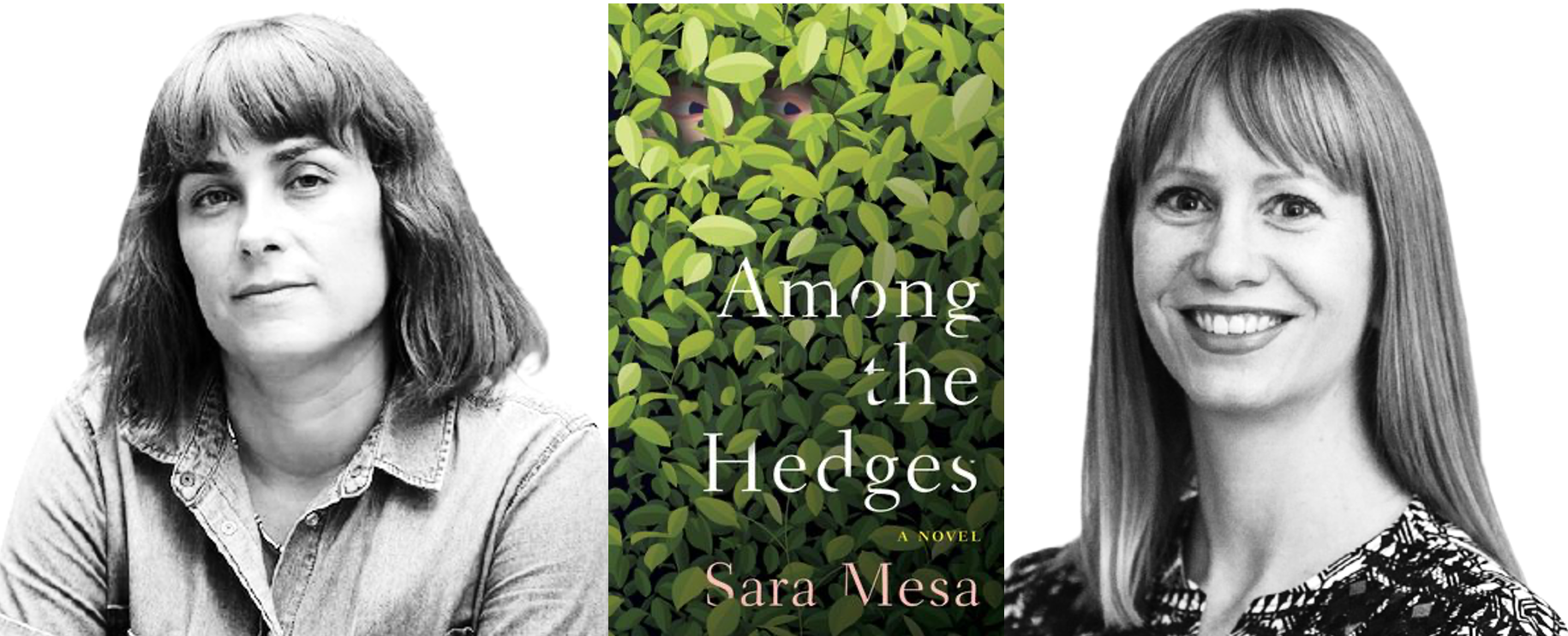

Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell.

She started to feel bad when her brother left. Her brother said he loved her, but it wasn’t true, because he left unapol-ogetically, claiming that he had to go. Had to? That’s what makes Soon the angriest: that he would disguise his freely made decision as an obligation. Is a person forced to do a master’s degree? That’s the first thing. And, in second place, why did he insist on studying abroad? Weren’t any of the programs in his hometown good enough for him? Or did he do it to escape, to get away from her? Of course, Soon had begged him to stay. She’d begged him in tears, she’d pleaded, but in vain. He looked at her with sorrow, he wrung his hands, assured her he also felt bad about leaving, very bad, and he said he was sorry, but his words—the words bad or sorry, for example—sounded so false they tore into her. Her brother is older, nine years older than her, and it’s been ten months since he left. Soon often goes into his room, still full of his clothes and books, to remember him more intensely, though it makes her even sadder.

Old Man listens attentively, nodding to show he under-stands her. Between them is a bag of Cheetos, which they casually share. She pauses to lick her fingers, blows a lock of hair off her forehead instead of touching it with greasy fin-gers. Her parents are older, she says, that’s why there are so many years between her and her brother. One time, Marga insinuated that she must have been one of those kids who are born by accident. Your parents made a mistake, she said, and you came by surprise. Marga was trying to upset her, but the truth is that being an unwanted baby fits perfectly with Soon’s vision of herself—I’ve always felt like I came from a different world, she says. Although in the end it wasn’t true that she was unwanted. She got up the nerve to ask her mother, who denied it roundly. She’d been wanted, very wanted, her mother insisted. Though I guess that’s no guarantee of anything, she concludes, scooping out the last Cheeto crumbs.

Physically, she doesn’t resemble anyone, which makes her happy. She is horrified by those daughters who are identi-cal to their mothers: it’s already clear just how they’re going to deteriorate over time. Though she is full of hang-ups, at least she doesn’t know how she will evolve, and sometimes she allows herself to dream up her own version of the story of the ugly duckling, in which she eventually becomes a lovely, alluring girl. Mysterious. Old Man has told her that her eyes are pretty, dreamy. Dreamy is a word that she finds interesting, even if she doesn’t know exactly what her friend is referring to. Like squinty?, she asks, like I was a little sleepy? Old Man smiles and says no: That would be more like drowsy!

(Old Man has a large vocabulary, she can tell he’s read a ton, though he won’t admit it and claims to read only magazines about birds. Well, he concedes, it could also be because he listens to the radio—every night, he listens to a call-in program where lonely people talk about their lives just so they can be heard. The program has existed for sev-eral decades, and there’s never any shortage of people who call in; there are always peculiar lives to tell, really strange lives that are also full of very strange words.)

Physically, Soon repeats, she doesn’t resemble anyone, not her father—who is tall and thin—or her mother—who is very blonde and has fine eyebrows and a much smaller mouth—and of course not her brother—who has a square face and freckles like their father. Oddly, the three of them share a certain bearing; you can tell they’re from the same family even though they don’t exactly have the same features. But Soon isn’t like them at all, she says, and when she says it she smiles with pride: lately, she’s pleased to feel different, and she doesn’t care that different could mean worse.

And him? Does he take after his parents? Old Man gives her a long, watery look; he shrugs his shoulders. What a question, he says: if he resembles his father, he also resem-bles his mother. He takes after them both, he adds: it’s inevitable! Soon doesn’t understand why his reply is accom-panied by that contorted expression, that pained melancholy. Maybe he misses his parents. Maybe his parents died a long time ago, maybe in an accident that he still hasn’t gotten over. When it comes to his family, Soon knows practically nothing, but it’s hard to ask when he reacts like that, ducking the question. Faced with the slightest pang of discomfort or pain, Old Man always changes the subject.

(There’s very little that Soon knows about Old Man’s life. So far: that he was beaten at school as a child, that he spent time in a hospital, that he lives alone on the eighth floor, that he’s worn the same coat for twenty years, that he doesn’t pay taxes because he doesn’t work, that he’s afraid—though less and less!—of being annoying, that he prefers pencils to pens, that he listens to call-in confessions at night on the radio. Things like that, incidental tidbits that he tells her unexpectedly and out of order. When he talks about sub-jects he knows about he’s didactic, organized, and repetitive, but when he talks about his own life—or mentions it, as if in passing—he does it in a quiet voice, with sentences that trail off and things left unspoken, as if there were no need to explain further.)

This excerpt from AMONG THE HEDGES was published by permission of Open Letter Books. Copyright © 2018 by Sara Mesa. Translation copyright © 2021 by Megan McDowell.