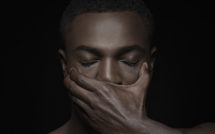

An introduction to our special feature on Race and Racism in Europe: The Urgency of Now.

Since the police killings of Breonna Taylor in March and George Floyd this past May, hundreds of thousands of protesters have taken to the streets across the United States to call for an end to police violence—and, sometimes, the abolition of police altogether. Black Lives Matter demonstrations persisted throughout the summer despite unusually high temperatures, extensive wildfires, a global pandemic, police violence against protesters, and menacing counter-protesters (indeed, murderous in the case of Kenosha). But as the readers of EuropeNow have likely noticed, these demands for a reckoning with institutional and systemic racism have not been limited to the United States. Cities like Amsterdam, London, and Paris have seen large protests both in solidarity with Black Lives Matter and in opposition to what activists describe as their own countries’ racism, both past and present.

Francophone scholar and filmmaker Dr. Mame-Fatou Niang recently described protests against police violence as part of France’s “Racial spring.”[1] Her expression alerts us to the democratic aspirations of anti-racists who seek to break the silence on race and racism in France. In so doing, Dr. Niang’s phrase, “Racial spring,” provocatively rejects the common French narrative that equality and republican unity can only be secured through race blindness. From demands for justice regarding the death of Adama Traore while in police custody in France, to the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston in the UK, racism and anti-racism remain key for understanding Europe’s past and its present. It is such discussions that we hope to engender with the newly formed research network on Race and Racism in Europe at the Council for European Studies (CES).

For decades, scholars studying race and racism in Europe, whether they were American or European, were warned against “importing American concepts” to European terrain. As experts on racial formation know full well, however, the American concept of race would not exist in the first place were it not for ideas born of Europe: specifically, ideas born of Europe’s Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, European colonialism and imperialism, and the European slave trade. True, anti-Blackness, Islamophobia, and orientalism are all influenced by the country-context in which they are found; nevertheless, they are found throughout Europe and its settler-colonial descendants (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, the United States), and they always share similar underlying logics of dehumanization, exploitation, possessive fascination, and fear that work neatly in tandem with capitalist accumulation and inequality. (We note that political scientist and fellow CES member Terri Givens has a forthcoming book, The Roots of Racism, on this very subject.) And this two-way ideological exchange is not just historical: on both sides of the Atlantic today, immigration and race have become entwined, so that far-right politicians can easily dog-whistle to racist supporters by shrugging off Syrian refugees as barbarian invaders and Mexican asylum seekers fleeing the violence of organized crime as drug dealers, criminals, and rapists. Drowning deaths in the Mediterranean and deaths by dehydration, exposure, and heat stroke along the US-Mexico border do not register as the loss of human life in the dehumanizing logic of racism.

It has been over thirty years since the publication of Paul Gilroy’s There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack and over eighty years since CLR James’s The Black Jacobins. Yet, Europeanists who seek to study race and racism in Europe continue to face pushback for their work—especially when they are Black, or otherwise non-white. At a roundtable at last year’s CES conference in Madrid discussing whether CES should have a Research Network dedicated to the study of race and racism in Europe, a graduate student made a plea for help justifying her decision to study race in Europe to an unimpressed dissertation committee that felt the topic did not merit study.

The essays in this special issue demonstrate the utility of centering race and racism in our analyses. Our first essay, by sociologist Ali Meghji, makes the explicit link between the denial of racism in the UK with its postcolonial crisis or “melancholia.” The UK remains wedded to its construction of itself as a “benevolent empire,” even in the face of present disproportionate deaths of BAME (British Asian Minority Ethnic) populations due to COVID-19. Britain’s denial of racism is also a denial of its colonial history and postcolonial present.

Our second essay, by Audrey Celestine, is a personal reflection of being a Black scholar in France researching and writing about race and racism in France. Here, she illustrates the complications of pursuing such scholarship, particularly when one is not white. Her description of identity as an object of daily negotiation rejects both communitarianism and abstract universalism, and challenges the accusation that to discuss racism in France is to be guilty of “importing concepts” from America.

Next, political scientists Saskia Bonjour and Sarah Bracke discuss how race functions in the construction of sexual predators in Europe, including how race and gender intersect to create a moral panic on behalf of white European women. Such a panic is mapped onto ongoing “crises” in Europe, including over an influx of migrants and refugees.

Our last essay by political scientist Michelle Weitzel examines an underexplored sensory aspect of racism: sound. In examining how French communities have criticized the Muslim adhan as communitarian noise pollution while simultaneously failing to perceive church bells as either a sound or a Catholic phenomenon, the essay explores how the borders of citizenship are policed via everyday soundscapes. Her essay also considers how culture serves as a site of racialization in France.

Finally, we end with an interview with historian Marius Turda on the historical relationship between eugenics and racism, the need to examine race and racism historically, and the relevance of both in our present moment.

As we were writing this introduction, Italian Foreign Minister Luigi Di Maio shared multiple photos of himself in digital blackface and Haitian-Italian designer Stella Jean boycotted Milan Fashion Week in protest of racism within the fashion industry. A Spanish journalist used racist language to describe the skills of footballer Ansu Fati. And Germany was dealing with the discovery of far-right police officers suspected of sharing Nazi propaganda. There is a pressing need for scholarly research and analysis about race and racism in Europe in all its forms, from microaggressions to state violence. Contrary to what some French political leaders and academics have recently suggested, this research is an essential part of moving past stereotypes, amalgams, and the taboos and silences of racism itself. In that spirit, the Race and Racism in Europe Research Network is pleased to present this series of essays and invites readers to follow the research of members of our network as we seek to center race and racism in our analyses of Europe.

Research

-

“Perception, Racism, and Islamophobia in French Soundscapes” by Michelle D. Weitzel

-

“Britain’s Postcolonial Crisis: The Denial of Racism in Little England” by Ali Meghji

-

“Europe and the Myth of the Racialized Sexual Predator: Gendered and Sexualized Patterns of Prejudice” by Saskia Bonjour & Sarah Bracke

Commentary

Visual Art

Interviews

-

“The Politics of Race and Memory in European Society: An Interview with Jean Beaman, Crystal Fleming, and Jennifer Fredette” by Laura Bartley

-

“Looking at Racism, Eugenics, and Biopolitics in Europe Historically: An Interview with Marius Turda” by Hélène B. Ducros

Book Reviews

Jean Beaman is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She was previously on the faculty at Purdue University and has held visiting fellowships at Duke University and the European University Institute (Florence, Italy). Her research is ethnographic in nature and focuses on race/ethnicity, racism, international migration, and state-sponsored violence in both France and the United States.

Jennifer Fredette is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Ohio University. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Washington, where she also obtained a certificate in Socio-Legal Studies. She studied Comparative Federalism at Sciences-Po Paris in 2006 and worked as a visiting research fellow at Sciences Po Bordeaux in 2008. Her areas of interest include constitutional law, comparative law, and sociolegal studies. She is currently conducting research on law and social movements in the French Caribbean.

Photo: Lincoln, Nebraska Black Lives Matter peaceful protest in Lincoln Nebraska | Shutterstock

Published on December 8, 2020.

References:

[1] Niang, Mame-Fatou. 2020. “France’s racial spring.” Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Brussels August 26, 2020. https://www.rosalux.eu/en/article/1761.france-s-racial-spring.html?pk_campaign=SocialMedia