Europe and the Myth of the Racialized Sexual Predator: Gendered and Sexualized Patterns of Prejudice

This is part of our special feature on Race and Racism in Europe: The Urgency of Now.

The Rise of the “Rapefugee”

It is sexual terrorism, a sexual jihad, and it happens everywhere in Europe […], everywhere where the red carpet is laid out for these testosterone bombs. (Wilders 2016)

“Testosterone bombs.” This is how Geert Wilders, leader of the Dutch radical-Right Freedom Party, and never shy for sweeping racist charges, spoke of Muslim immigrants in 2016. In a statement posted on YouTube, Wilders called for a Muslim immigration ban in order to stop what he referred to as a “rape epidemic.” Pending such a ban, he proposed locking all male asylum seekers in reception centers. Wilders published his statement in the wake of the 2015-2016 New Year’s Eve events in the city of Cologne, when groups of men robbed and sexually assaulted hundreds of women (De Hart 2007). Much has been written about the events, with many conflicting accounts of what happened—notably about the numbers of perpetrators and victims involved—or about the organized or spontaneous character of the mob. But a few things are consistent: many women were sexually assaulted that night, the perpetrators were described as North African or Arab, and moral panic surrounded the event. The moral panic, however, was not so much about the vexed question of sexual violence at large, but rather, about the presence of racialized men in the cities of Europe. As public narratives and frames on what had happened were elaborated, the spotlight turned to these men racialized as non-white and not belonging to Europe, qualified alternately as migrants, Muslims, or refugees. While a sexualized fear for refugees had been brewing, both in the mainstream media and on the streets, the moral panic following the sexual assaults in Cologne cemented the central role of a new figure which PEGIDA would rapidly baptize as the “rapefugee” (Bracke and Hernandez Aguilar 2020).

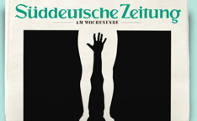

The narrative has gained traction all over Europe: non-European male immigrants represent a sexual threat to European women. In the wake of the sexual assault in Cologne, the narrative was elaborated in a vast array of cultural productions and representations—perhaps most loudly on the side of parties and activists with an explicit anti-migration and/or anti-Muslim agenda, but also pervading mainstream politics and media in Europe. A quick glance at the covers of widely read magazines in the first months of 2016 shows us these representational politics in action, with variations of images of black and brown hands assaulting white female bodies. The February cover of the Polish magazine Wsiecki makes it very explicit: an image of a blond woman draped in a European flag violently harassed by dark brown hands, entitled “the Islamic rape on Europe” (Wsiecki 2016).

This narrative is all but new: it has been told and retold for centuries, and this intimate familiarity probably contributes to its strong resonance in contemporary European politics and societies. When Europeans invented race as we know it today, as part of their colonial enterprises, including systems of slavery and genocide, they relied on stories about dangerous and violent racialized “others,” who needed to be controlled and “civilized” by white people (Hall [1994] 2017; Baum 2006). Representations of non-white men as sexual predators preying on white women were central to these stories. The figure of the racialized sexual predator, in its many iterations, has indeed been at the very heart of European racism and white supremacy. In this essay, we seek to situate this current iteration, the “rapefugee,” within a broader context and unpack what this new figure, or better this new articulation of an old trope, is doing today.

Figure 1 Süddeutsche Zeitung, 9 January 2016

Figure 2 Focus, 9 January 2016

Figure 3 wSIECI, 16 February 2016

Figure 4 NRC, 9 January 2016

Figure 5 Vrij Nederland, 6 February 2016

European Fantasies, Fantasies of Europe

Throughout history, and across the globe, perceived threats to the nation have often been sexualized and represented in terms of a rape threat to “our” women. Such representations have been part and parcel of the gendered and sexualized constructions of the nation and its others (Yuval-Davis 2008). Here, we are particularly interested in how such representations have been mobilized in the context of the modern European nation-state, that is to say, in a social formation often qualified as “modernity” that has been characterized by European colonial and imperial projects. European colonial rule was grounded in a belief in the superiority of European civilization and in the supremacy of Christianity (subsequently in secular versions) and the superiority of what was considered to be the white race (Anidjar 2006). Gender and sexuality were crucial to the articulation of these civilizational and racist ideologies, and racial boundaries were drawn in the realm of the intimate: Europeans defined themselves as different from and better than the people whom they colonized, by pointing to the alleged superiority of, among other things, European womanhood and manhood, European dress, European homemaking, European parenting, and European marriage and sexuality (Stoler 2001; Hajjat 2012). The dehumanization of colonized men and women, as the philosopher María Lugones has argued, meant excluding them from all that made up manhood and womanhood for Europeans: colonized men were denied autonomy, citizenship, and the role of breadwinner and pater familias; colonized women were denied dedication to motherhood and domesticity, as they were often separated from their children and expected to do (hard) labour outside of their homes (Lugones 2010).

Sexuality was a crucial terrain upon which this dehumanization occurred: white European representations have consistently attributed colonized and enslaved men and women with an animal-like sexuality, with strong sexual drives and few—if any—inhibitions. The literary critic and Black feminist theorist Hortense Spillers (1987) developed the concept of “pornotroping” to think through how the violence inflicted upon enslaved bodies became tied up with the (sexual) pleasure experienced by the sovereign subject. Gender and sexuality studies scholar Anne McClintock (1995, 22) characterized the colonies as “porno-tropics for the European imagination—a fantastic magic lantern of the mind onto which Europe projected its forbidden sexual desires and fears.”

While the sexualisation of “others” has a longer genealogy, nineteenth-century scientific racism firmly inscribed such fantasies within the concepts, myths, and imaginaries of race that are still with us today. Modern understandings of race, in other words, have been as obsessed with the size and shape of sexual organs of racialized people as they were with the size of their skulls (Saint-Aubin 2002). In these racist fantasies, women of colour were commonly cast as sexually available and men of colour were consistently cast as a sexual threat. Both of these tropes were subsequently invoked as justifications for the systemic and institutionalized (sexual) violence against racial “others” (hooks [1981] 2015).

Old Tropes in New Articulations

If this is, in broad strokes, the horizon in which the figure of the “rapefugee” enters the scene, the particular articulations of the trope of the racialized sexual predator matter. The narrative of the sexual threat posed by racialized men is not a singular story: it is told and retold in different ways and with different protagonists (note the sliding Arab/Muslim/refugee references in the Cologne case), in different contexts and with different purposes. Attending to the specificity of these articulations while mapping out the connections and resemblances between them, sheds lights on the different dimensions of European constructions of self and other, and the political and economic context in which these threatening figures come to life.[i] In an early and seminal analysis of one of these persistent mythical figures, i.e. “the Black rapist,” Angela Davis scrutinizes the articulations within which this figure was animated. Relying on the work of Ida Wells and Frederic Douglass, Davis lays out how the myth of the Black rapist was conjured up in post-Civil War times in the US when violence and terror against Black communities needed a new kind of justification. While the lynching of Black men on the basis of rape accusations hardly occurred when the slavery system was in place, nor during the Civil War, it took on massive proportions and became an indispensable part of the political economy of the Reconstruction era. The trope of the Black sexual predator, in other words, found fertile ground in a political, economic, and cultural context in which a white European-descendent population lost the technologies of domination they had relied on for centuries (i.e. the slavery system) and was frantically searching for new ones (Davis [1981] 1983).

At the same time, another articulation of the racialized sexual predator was activated on the other side of the Atlantic, in the midst of the rise of nineteenth century European antisemitism. In 1888, the city of London as well as other parts of the UK and Europe were in the grip of Jack the Ripper, and both the police and the public at large speculated that the serial killer must be a Jewish man. As the cultural and literary historian Sander Gilman argues, Jack the Ripper was the emblem of sexual perversion out of all control, of deviant sexuality and violence. The fact that many of the victims had certain organs removed, invoked the charge of ritual butchering: Jack the Ripper was framed as the shochet, the Jewish ritual butcher (Gilman 1991).[ii] The descriptions of Jack the Ripper that circulated among the public amounted to a caricature of the Eastern Jew, and a high proportion of the men who were questioned in the case were Jews. While the killer was never identified at the time, the memoires of the police officer in charge, Sir Robert Anderson, conveyed his deep conviction that the killer must have been a Jew (Gilman, 115). As the killings continued throughout the year (a total of twenty killings were potentially ascribed to the same serial killer) and the representations of Jack the Ripper as Jew flourished, repercussions towards the Jewish population became tangible, including the treat of a pogrom against Jews. UK’s most famous serial killer was a hot topic of debate in the international press as well, and in various German newspapers, Jack the Ripper was framed as part of “the international Jewish conspiracy” (Gilman, 119). The trope of deviant and dangerous Jewish sexuality preceded this particularly intense moment of the representation of the male Jewish sexual predator, and it continued to be reworked and animated in the decades to come. When the Nazi party rose to power in Germany in the 1930s, Nazi propaganda was replete with images of the denigrate Jewish sexual predator, posing a serious threat to white “Aryan” femininity and (the “purity” of) the German nation—images that played a critical role in the systematic dehumanization of the Jews.

In yet other contexts and articulations, European colonizers across the globe fretted over “the Black peril,” as the British called the sexual threat that male colonized subjects purportedly posed to white women. In Kenya and Southern Rhodesia, citizens’ militia were created in the 1920s and 1930s to protect white women from being raped by Black men, as postcolonial studies scholar Ann Stoler documents, which included “white ladies” being taught to handle a rifle for “self-defense.” New Guinea introduced the death penalty in 1926 for the attempted rape of a white woman; in the Solomon Islands the penalty was public flogging. Stoler (2002, 58-59) emphasises that none of these public outcries were caused by actual incidents of sexual violence against white women, rather, they were responses to perceived threats to the stability of colonial rule, emanating either from resistance by the colonized, or from tensions within European communities. In the words of legal scholar Betty de Hart (2007), “Discourses on the sexuality of colonized men functioned to maintain [the] colonial order” (41).

These representations travelled back to the European metropoles where they were re-articulated at the end of WWI and in the Interbellum, after the Treaty of Versailles had granted the Allies the right to occupy Rhineland until 1935. As France stationed its “colonial” soldiers (notably from Senegal, Madagascar, Algeria, and Vietnam) in Rhineland, a moral panic emerged in Germany, known as “the Black Horror on the Rhine” or the “Black Shame.” Central to the moral panic were newly elaborated representations of Black soldiers as sexual predators and rapists of white women, in public debates that were concerned with the boundaries and identity of the German nation.

Gender and Race in the ‘Refugee Crisis’

We return to the newest member of that old and extended family of racialized sexual predators. The figure of the “rapefugee” in Europe occurs in a specific context: a political crisis that followed the rise in numbers of refugees making their way to Europe in the mid-2010s, a political crisis rooted not only in decades of increasing economic precarity in Europe, but also in shifts in European public and political discourses since the 1990s, in which the racist constructions of “civilizational thinking” focused on the difference between ‘Islam vs. the West’ have become today’s common sense. The “rapefugee” articulates these cultural, political, and economic elements, while serving a distinct political agenda: rendering migration to and seeking refuge in Europe threatening, through articulating immigration of non-white people with rape—the rape of “European” women, equated with the rape of Europe.

This articulation of migration-as-threat made tangible through sexual violence and rape is captured in a disturbing way in the particularly brutal and dehumanizing political cartoon by Laurent Sourisseau published in Charlie Hebdo, where the iconic image of the small lifeless body of the toddler Aylan Kurdi on a sandy Turkish beach is juxtaposed with a drawing of a grown-up Aylan threatening to grab a woman’s behind. ‘What would have happened if Aylan grew up?’ the cartoonist asks, and answers: un tripoteur de fesses en Allemagne—someone who gropes at women’s behinds in Germany.

We cannot afford to be surprised by the emergence of these sinister and dehumanizing figures or myths. Indeed, such surprise, and innocence,[iii] could only exist in conditions of severe historical amnesia. As hundreds of thousands of people embark on dangerous journeys to flee uninhabitable livelihoods and seek refuge in Europe, and tens of thousands lose their lives along the way, those with vested interests in framing migration as a threat—a threat to identity, a threat to economy, a threat to the social order—and in ensuring that the European borders, both material and symbolic, are as closed and controlled as possible, need ammunition for their narratives of threat. The racialized sexual predator is a familiar story to turn to. It is also a very powerful one. Since the rise of the “rapefugee,” different European countries implemented laws that made it easier to expulse asylum seekers or refugees convicted for criminal acts, including sexual crimes (De Hart 2007). And European officials have proceeded to select single women and families for resettlement but never single men, who are considered likely to lack ‘integration potential’ and to commit (sexual) offences (Welfens and Bonjour, forthcoming).

Yet situating the story of the racialized sexual predator within the racist politics that bring it to life, which requires recognizing the multiple and colonial genealogies of European racisms, and recognizing that sexual fears and fantasies have always been at the heart of European racisms, gives us a chance at dismantling the power and appeal of such narratives. And as old stories shrink and shrivel, new stories about identities and belongings in Europe have more chance to grow.

Saskia Bonjour is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. She is the principal investigator of the research project Strange(r) Families. Political Contestation over Family Migration Rights for Non-Normative Families, funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

Sarah Bracke is Professor of Sociology of Gender and Sexuality at the University of Amsterdam. She is the principle investigator of the EnGendering Europe’s’ Muslims Question’ research project funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

References:

Anidjar, Gil. 2006. “Secularism.” Critical Inquiry 33, no. 1 (Autumn): 52-77. https://doi-org.proxy.library.ohio.edu/10.1086/509746

Baum, Bruce. 2006. “Enlightenment, Science and the Invention of the Caucasian Race, 1684-1795.” In The Rise and Fall of the Caucasian Race. A Political History of Racial Identity, 58-94. New York: New York University Press.

Bracke, Sarah and Luis M. Hernandez Aguilar. 2020. “‘They love death as we love life’: The ‘Muslim Question’ and the biopolitics of replacement.” British Journal of Sociology 71, no. 4 (September): 680-701. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12742.

Davis, Angela Y. [1981] 1983. Women, Race & Class. New York: Vintage Books.

De Hart, Betty. 2007. “Sexuality, Race and Masculinity in Europe’s Refugee Crisis.” In Migration on the Move: Essays on the Dynamics of Migration, edited by C. A. F. M. Grutters, S. Mantu, and P.E. Minderhoud, 27-53. Nijmegen: Brill.

Gilman, Sander L. 1991. The Jew’s Body. New York: Routledge.

Grossberg, Lawrence. 1966. “On postmodernism and articulation: An interview with Stuart Hall.” In Stuart Hall: Critical dialogues in cultural studies, edited by D. Morley and K. Chen, 131–150. London: Routledge.

Hajjat, Abdellali. 2012. Les frontières de l’ “identité nationale”. L’injonction à l’assimilation en france métropolitaine et coloniale. Paris: La Découverte.

Hall, Stuart. [1994] 2017. The Fateful Triangle. Race, Ethnicity, Nation. Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press.

hooks, bell. [1981] 2015. Ain’t I A Woman. London: Pluto Press.

Judd, Robin. 2009. Contested Rituals: Circumcision, Kosher Butchering, and Jewish Political Life in Germany 1843-1933. Ithaca: Cornell University.

Lugones, María. 2010. “Toward a Decolonial Feminism.” Hypatia 25, no. 4 (Fall): 742-759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2010.01137.x

McClintock, Anne. 1995. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. London: Routledge.

Saint-Aubin, Arthur F. 2002. “A Grammar of Black Masculinity: A Body of Science.” The Journal of Men’s Studies 10, no. 3: 247–270. https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.1003.247

Spiller, Hortense J. 1987. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer): 64-81. https://doi.org/10.2307/464747

Stoler, Ann L. 2001. “Tense and tender ties: The politics of comparison in north American history and (post) colonial studies.” The Journal of American History 88, no. 3 (December): 829-65. https://doi.org/10.2307/2700385

Stoler, Ann L. 2002. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wekker, Gloria. 2016. White Innocence. Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Durham: Duke University Press.

Welfens, Natalie and Saskia Bonjour. Forthcoming. “Families first? The Mobilisation of Family Norms in Selection Practices of Refugee Resettlement.” International Political Sociology.

Wilders, Geert. 2016. “Mannelijke asielzoekers opsluiten in AZCs.” Translated by Saskia Bonjour and Sarah Bracke. YouTube video, 3:06, January 18, 2016, https://youtu.be/c7NshmTyizU.

Wsiecki. 2016. Cover image. February 13. 2016. https://www.wsieciprawdy.pl/wsieci-islamski-gwalt-na-europie-pnews-2681.html

Yuval-Davis, Nira. [1997] 2008. Gender & Nation. London: SAGE.

[i] We draw upon Stuart Hall’s understanding of articulation, as a way to account for how the cultural (representational) relations to political economy, in a way that does justice to the contingent character of social formations (Grossberg 1966).

[ii] Gilman reminds us that this representation of the Jack the Ripper as the Jewish ritual butcher occurred in a moment of public campaigns by anti-vivisectionists in England and Germany against kosher butchering. See also Judd (2009).

[iii] See Wekker (2016).

Photo: Bregana, Slovenia – September 20, 2015 : A large group of male syrian refugees at the slovenian border with Croatia. The migrants are waiting for the authorities to open the border crossing | Shutterstock

December 8, 2020.