Discovering (M)othertongues: A Reflection on the Conception of a Student-Run Publication

This is part of our special feature, Networks of Solidarity During Crisis.

This is part of our Campus Spotlight on Bennington College.

When we took the course, “In Translation: Lives, Text, Cities,” at Bennington College in Fall 2017, we were presented with a class that would allow us to study writers who live in translation —writers like us. We were eager for the opportunity to discuss the ideas that the texts presented us—ideas like in-betweenness, pluralism, and hybridity, ideas so prevalent in our daily lives—but what we did not expect was the strong disparity between our experiences and the ones that dominated the anthology we studied, Lives in Translation: Bilingual Writers on Identity and Creativity. We disagreed with the notion that a bilingual life was somehow a dual or binary life, knowing that our multilingualism and in-betweenness didn’t create contradictory lives and stories, but enriched ones. With this perspective in mind, we began to create a variety of essays from our experiences, on a wide range of subjects, including the reclamation of Indian forms of English (Soumya Rachel Shailendra ‘21) and linguistic activism in Belarusian education, which explored how language can be used as both a tool for political repression and for resistance (Hanna Karnei ‘21). These essays inspired us to create a space to share work beyond binaries, and were the first seeds from which (M)othertongues grew.

We commenced in the second half of the Fall 2019 term within a class called “Living in Translation: A Student-Run Literary and Cultural Publication” taught by Marguerite Feitlowitz. There were fourteen of us, representing Pakistan, El Salvador, Ecuador, Mexico, England, Nepali, China, Germany, and Malaysia. The air of our first class, in the brisk late-October of the Vermont hills, was charged with the potential energy of the inevitable discoveries we would be making over the next months. We discussed an excerpt from From Nomenclature, Miigaadiwin, a Forked Tongue by Aja Couchois Duncan, a piece that was the first of many that could not be understood in a vacuum, pieces that insist on research and effort from the reader in order to begin to understand. When it came time to discuss the publication, we were surprised to find that we had difficulty determining the focus of our magazine. The impetus was clear—that’s to say, we knew why we were cramped around a table in a Southern Vermont classroom to discuss what it means to live in translation—yet we couldn’t articulate the answer to a crucial question: what can we publish to further explore our understanding of hybridity?

With these questions in mind, we went around the room, taking turns to discuss what we felt we most wanted to explore in our first issue. One area of discordance regarded the subjectivity of the phrase “living in translation.” Even though the magazine was conceived in a course on literary translation, a few of us weren’t actually fluent in multiple languages. We learned that one can still experience the translation process outside of language, whether that be the translation of self from one’s English identity to their a familial home-self in Iran, or the act of listening to one’s grandmother as she ventures to translate her life story of refuge and war across years and oceans.

While listening to each other, we soon realized that the differences in our voices allowed for depth and richness that no one alone could design. Our disharmony was the key, and our publication would seek to explore just that—the disharmony, in-betweenness, and hybridity that we felt within our individual identities. Thus, we constructed our mission statement soon after:

We are living in a multicultural, multilingual era, creating new spaces for hybridity that unsettle cultural binaries of the past. We believe it is important to complicate the dichotomous idea of here and there-ness that has dominated historical narratives. We aim to create a publication that looks to address themes such as migration, diaspora, in-betweenness, identity, cultural diversity, and language.

Our name took much longer than our mission statement to be decided on. One suggestion was In the Seam, an image that represents the harmonious consolidation of two originally distinct things. But translation, someone pointed out, is not always harmonious, and hybridity is not stagnant like a seam. The name we decided on, (M)othertongues, represents how an “other” tongue can also be a mother tongue—that the latter is not always singular. By conflating “other” with “mother,” our publication’s name expresses the naturality of hybridity—that here, singularity is not the norm.

Neither is monolingualism. Like most of the world, our team is comprised of people to whom the notion of living in one language is inconceivable. Some on our team speak two or three languages just at home, such as our poetry reviewer Hafsa Zulfiqar ‘22, who lives in Urdu, Sindhi, English, Hindi, and is learning French. The other languages spoken by are team are Spanish, Farsi, Nepali, Polish, Mandarin, German, and Malay. Some of these languages were spoken by multiple people in the room, yet we learned that a shared “mother tongue” between didn’t mark an identical relationship with language; one of our team, born and raised in China and educated in an English-speaking international school, once asked the other Chinese-language speaker in the room (who was primarily educated in Chinese) to read their writing, insistently apologizing that their reading skills weren’t as proficient in Chinese. It became abundantly clear, then, that an individual’s relationship with a language can be unique from others’—and that just because someone is more literally proficient in one language does not diminish their identification with another.

At the end of 2019, we were able to produce a “first draft” digital publication of our team’s work. As well as giving us more time during our short seven-week class to refine technical aspects such as the website and call for submission, the draft-publication granted us the opportunity to personally realize our mission statement through creating our own work. Most of us were writing students—the course was classified within the Literature department and instructed by Marguerite Feitlowitz, an author and literary translator—and we produced poetry, essays, translation, or a hybrid-genre piece for publication. Some writers also produced multi-media work, combining the written-word with forms of collage. Alyssa Pong ‘23 produced perhaps the most divergent and inventive piece: I Don’t Know What to Say, a film of improvised dances to oral narratives from primarily international Bennington students. Alyssa says it is “a collection of stories and reflections told in multiple languages and translated through voice and body.” Regarding her experience creating the project, she says, “one thing that intrigued me about the people I met were their stories. Stories that began with numerous renditions of ‘I don’t know what to say’ and continued as tales of change, identity, leaving, and family told in a host of languages. Being a part of a community made up of such complex individuals, I wondered just how we can begin to understand one another. Maybe through words or maybe through movement. These videos are the manifestation of that process.”

In Warsaw—written during for “first draft” publication but included in the first official issue, which launched in May 2020—board member Michelina Ainol ‘21 attempts to understand her city’s burdened past by reading and translating poet Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński. She writes,

In an attempt to make peace with the ever-present history of the place I was born into, I decided to dive deeper; it seemed too easy to simply ignore the signs and landmarks that in one moment became so obvious to my eyes. I wasn’t the first to become obsessed with Warsaw’s complex layers of history and it didn’t take me long to come across the bards of the city who during the occupation took it upon themselves to document the fate of the capital. They might have had the future generations of citizens in mind, or they could have done just for their own sake, treating art as a way to deal with the violence that fell upon their city.

In An Elegy for my Mother’s Tongue, published in May, Soumya Rachel Shailendra ‘21 reflects on “loss, belonging, and lamentation through the lens of language.” She writes,

I was too young to deliver a eulogy for my grandfather. I did not speak Malayalam, neither did I have the words to accurately convey the loneliness that had tugged at my heart in his absence. No, I could not comprehend death—its infinitude or momentum. But I inhabited its space by navigating his public funeral like a stranger. I was still searching for a language of lament, a language that could dignify my private grief publicly.

Juan Lopez ’21 tells us that his piece, A Documentation of Youth, was “inspired by the migration to the Bronx that took place due to the construction of the Cross-Bronx expressway and the urban decay that took place after.” He writes,

I hate the highway. The highway that tore apart the city and split it in two. The city I will no longer come to call home. Mama says they built cities for children. Children like us. The ones that sit upright with attention to watch the sunset. So that when they look up and the sun disappears into the rumble of glass and metal they will see their utopias in the angular buildings of the city. Grass no longer grows from this soil. Instead, it births highrises and highways. We do not complain. Our streets do not bring us to grand cathedrals or skyscrapers. They lead to liquor stores.

Lopez’s piece fit well within our mission statement—he elegantly explored both migration and identity, specifically how the former can disturb the latter by the corruption of a home—yet in an unprecedented way; his piece was inspired by an event of domestic mass migration, an experience that we had never read about, much less considered and discussed. This piece also brought to mind the subject of gentrification, the opposite side of the coin to Lopez’s piece—rather than community decay that he illustrates, where locals find themselves trapped in a neighborhood that is a skeleton of what it once was, gentrification exists as a pervasive form of forced migration and displacement that is rarely recognized as such, despite its impact on innumerable individuals and families. This revealed what we learned to be a fundamental strength of our publication: that our contributors expand our collective understanding of the themes we seek to explore—of identity, hybridity, language, migration, and home.

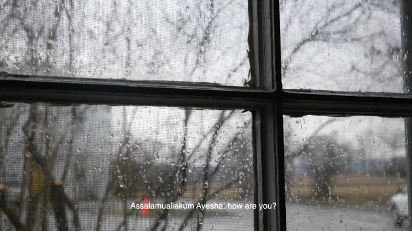

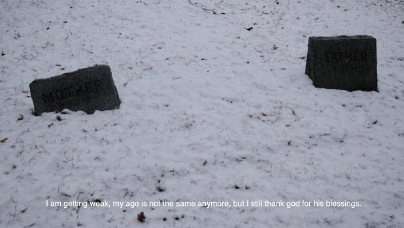

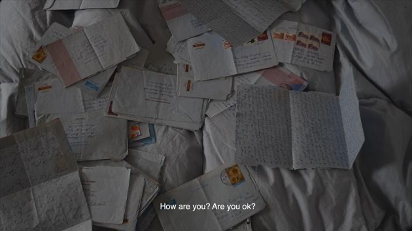

As a group of mostly literature students, the quality of writing submissions for our first official issue lived up to our expectations of what we had assumed our talented peers were capable of. What surprised us, however, was the wealth of visual arts submissions which comprised the majority of the work submitted for our first publication. In her experimental short film, 0:28, Ayesha Bashir ‘22 plays voice messages in Urdu sent by her mother in front of “cold visuals that convey emptiness, alienation, and remoteness.”

Stills from Ayesha Bashir’s experimental short film 0:28

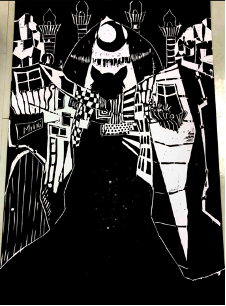

Throughout multiple prints, Melih Meric ‘21 uses printmaking to create continuous abstract patterns, capturing “the essence of orientalism, the structure of the living.” Melih, a student of visual arts and Islamic art history, explains,

I like to combine my experience living in a city with absurd fundamentals of daily life dynamics and what I create. I find value in works that capture the essence of orientalism, the structure of the living. I work with the idea of remembrance, especially specific patterns from Turkish culture, often imitating traditional tile motifs.

From left to right: Lamp, Midnight, and Pattern (Printmaking Pieces) by Melih Meric

As the Fall 2020 term commences, and the Bennington College Campus floods with students from around the world, the future of (M)othertongues is at the forefront of our minds. We know that plans for continuation will have to reckon with the loss of our graduated class, but we hope to use this as an opportunity to expand our team—because if there’s one thing that we’ve learned, it’s that our publication is made strong by the wide array of experiences around us. To view the full work of the artists mentioned above (and much more) check out our website here. We hope their stories expand your understanding of what it means, exactly, to live in translation—just as we hope future submissions expand our own.

Valeria Sibrian is the Managing Editor and Art Editor of (M)othertongues and a senior at Bennington College who is studying Forced Migration and Painting. Their work is focused on the role memory has in understanding and archiving the migrant experience at the U.S/Mexico border.

Sarah Lore is the Prose Editor of (M)othertongues and a sophomore at Bennington College, studying creative writing and literature.

Published on October 13, 2020.