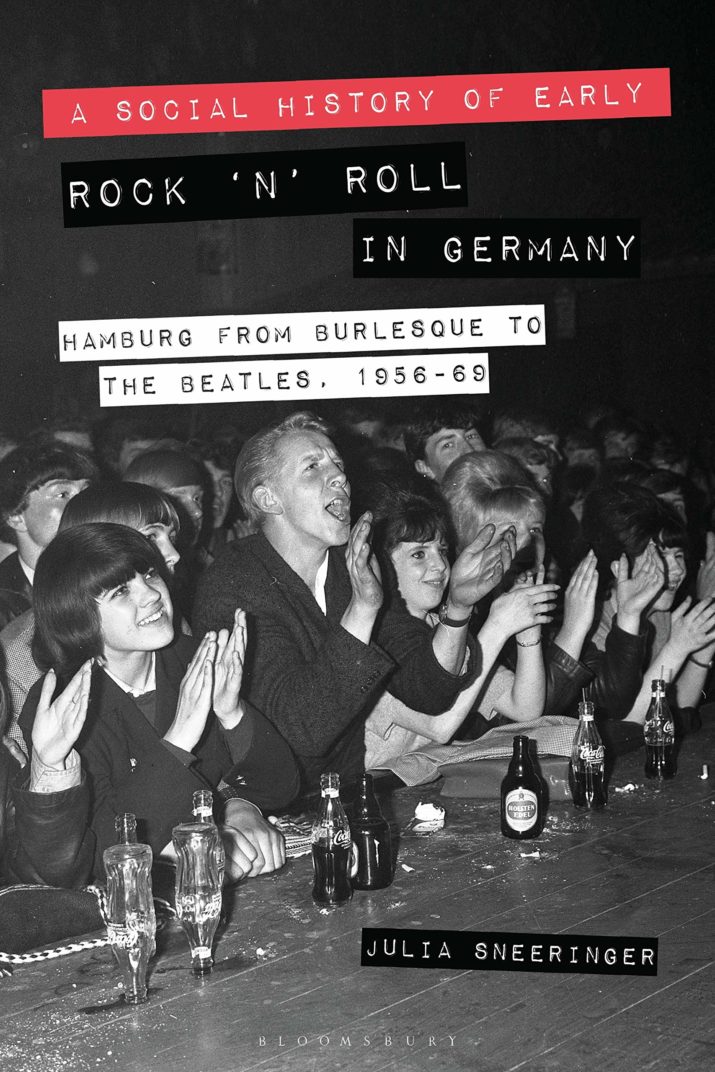

A Social History of Early Rock ‘N’ Roll in Germany: Hamburg from Burlesque to the Beatles, 1956-1969

The Beatles: what more is there to say about the band that transformed global popular culture? A casual survey of the Library of Congress reveals over a thousand titles. When a band—its members, music, and impact—have all been so thoroughly chronicled and analyzed, it is tempting to think there is nothing meaningful left to say. Historian Julia Sneeringer’s recent publication A Social History of Early Rock ‘N’ Roll in Germany: Hamburg From Burlesque to the Beatles, has found one of the rare blind spots in the voluminous literature on the Beatles, and on the development of rock music outside of the US-UK context. Her history of Hamburg’s post-war entertainment industry captures a moment of nascent global youth culture, but in a location not often associated with international influence making. By combining political and economic histories, fan culture, musical studies, and a few lurid details, Sneeringer composes a succinct and insightful narrative, decentering the “great men” of rock in favor of interrogating myriad others involved in “musicking.” She argues that important practices, which shaped European youth culture, took root in Hamburg during the German Miracle, and that the city, and the St. Pauli neighborhood in particular, was fertile ground because of its history as a tolerant cosmopolitan port city with a vibrant and risqué entertainment industry. Her history emphasizes the importance of local cultural histories and political economies of place in influencing the production and reception of the arts, industry, and emergent cultural practices.

The book begins with an excursion into the history of St. Pauli as an entertainment district, from a space beyond the walls of the thirteenth-century city-state of Hamburg through rebuilding after World War II. The chapter points out Hamburg’s historical cosmopolitanism and the role of sex work and entertainment that combined to cultivate the ground on which rock ‘n’ roll would be transformed from its southern American roots in rhythm and blues. The following chapter is a finer grained approach, examining the advent of clubs that catered to younger patrons and the visions and business models that enabled this transformation in the context of the German Miracle. The following three chapters delve into musicians, fans and audiences, and authorities, respectively. Collectively they put human faces on Hamburg’s history: the links between Hamburg and Liverpool, how locals shepherded young Brits through the rough streets of St. Pauli and taught them to love Hamburg (and Germany by extension), changing notions of youth, sexuality, gender roles, and national identity, and government resistance to youth upheaval and independence. The final chapter explains how the most vibrant rock ‘n’ roll scene in Germany met its demise at the hands of aggressive new genres of rock, discotheques, and cultural conservatism.

Sneeringer expertly crafts several arguments that are essential to expanding dialogue about rock’s global impact. The first is the importance of entertainment space as a terrain where experiments in subjectivity occur. As much as escapism is part of entertainment, new freedoms, social roles, and behaviors exercised in dance halls were integrated into the daily lives and identities of Hamburg’s youth. While these spaces were no panacea, and were not immune from the strictures, hierarchies, and violence of traditional society, practices learned in entertainment districts influenced everyday life. The second is that fans of rock made themselves part of the spectacle and exerted influence on musicians and scenes. Without the (now) nameless, mostly young fans that populated the bars and dance halls of Hamburg, The Beatles, or any of the other early British rock groups who cut their teeth in Hamburg, would not have had the sweeping influence in Germany, the UK or US that they did. As the Beatles performed on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” they brought pieces of Hamburg with them. This exchange between audience and musicians was produced in multiple aesthetic realms (sonic, sartorial, coiffure, art) and facilitated by the relative closeness in age of musicians and fans. The final argument is that entertainment is often the dynamic vanguard of innovation—it heralds changes in subjectivity, policy, economy, and social relationships (at times of the international sort). This final point is particularly relevant as we collectively stare into a world shaped by COVID, populism, and a disintegration of post-war economic relationships and political alliances. In a moment when American K-pop fans can disrupt a presidential rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, using a Chinese-made app, the lessons from 1960s Hamburg retain their relevance.

The overall strength of Early Rock ‘N’ Roll is the author’s thorough use of mixed methodology. The text relies on historical documentation—newspapers, advertisements, historical monographs, fan magazines, diaries, recordings, police reports and legal documentation—and includes engagements with gender and sexuality theory, biography and autobiography, political economy and cultural/sub-cultural theory, law and public policy. The text synthesizes these multiple narratives into a succinct overview, a snapshot of a moment that petered out in 1969 (ironically because the revolution in popular music that the Beatles began, what critic Elijah Wald hears as the end of rock ‘n’ roll and the beginning of rock, fractured the aesthetics and business models of rock ‘n’ roll dance music-oriented club owners). The mixed method approach, and one that brackets deep discussion of “the music” in technical terms, instead centering fans, business owners (of all sorts, as connections between music consumption, promotion and recording, sex work, and commodities are intertwined), media, and government, opens up ways of interrogating the terrain on which music flourishes and undercuts some myopic musical discourses that focus solely on sound.

This methodological approach performs two essential functions. The first is to expand musical histories. Even popular music histories, written in the shadow of “great man” critiques (see monographs on Beethoven or Wagner for examples), tend to focus on music makers as agents, and on fans as the lucky recipients of their artistic talent and vision (literature on the Beatles largely reinforces these notions). There are exceptions to this (Trish Rose’s Black Noise; Alex Zolov’s Refried Elvis, George Lipsitz’s Footsteps in the Dark, Debra Pacini-Hernandez’ Oye Como Va!), but Early Rock ‘N’ Rollsignificantly de-centers musicians and puts their success into robust historical, aesthetic, cultural, geographic, emotional, and embodied context. This enables music to be understood holistically as collective phenomena that allows for consumers to make meaning, businesses to make money, and officials to make policy alongside musicians making music.

The second function is that the text opens up the study of music culture to scholars and students who are not necessarily trained in the academic discourse of music. While the performance, composition, and capturing of musical sound in print for analytic purposes is an essential element in music scholarship, these are not, and should not be, the only foci of music scholarship. Sneeringer is right to cite the work of Christopher Smalls, Simon Frith, and Ruth Finnegan, all of whom insist on viewing music as social life, spaces where social life creates music and vice versa, and insist on researching and writing in this spirit. All participants that make up a scene are appropriate subjects and agents of history. Sneeringer’s approach also makes the book accessible to scholars and students who are not versed in the vocabularies of ethno/musicological research or methods of musical analysis, and serves as an important contribution to students of contemporary popular culture and political economy.

While the brevity and focus of the book is admirable and makes for both an enriching and interesting read, there is a critical oversight that is worth bringing out. When addressing audiences’ preference for US and UK acts over German bands, Sneeringer uses the term “authenticity:” German youth saw UK acts as closer to the US and to American Blackness, and therefore more authentic. Taste hierarchies that started with language (English) and origin (US first, then the UK, and then Germany) depended on this notion of authenticity and fans’ emotional and intellectual reactions to it. These notions of authenticity were in turn reinforced by a knowledge economy that produced cultural capital. However, the term authenticity is not sufficiently unpacked (there is a long legacy of debating this term in folklore and popular music studies). This is a missed opportunity, partly because the concept of authenticity that shaped thought in the US and drove the folkloric search for African-American (as well as Indigenous and Appalachian) music are rooted in the work of Johann Gottfried Herder, whose ideas loom large over the formation of European Ethno-nationalism that youth in Hamburg were searching to distance themselves from. An interrogation of this term, in light of rock ‘n’ roll fans’ attempts to create separation from the Third Reich and find community with English-speaking artists from the UK, while simultaneously navigating German gender roles, expectations, and strictures in a former red-light district in the midst of an economic boom, would yield a compelling narrative of the contradictions, erasures, and unevenness of global exchanges, local identity formation, and collective appropriation.

Early Rock ‘N’ Roll is an excellent addition to the literature to popular music studies and rock in particular. It illuminates a historical period where the genre rules of popular music and industry infrastructure had not yet erected fences between musicians and audiences and laid the groundwork for popular culture as the signature of mass democracy. Sneeringer humanizes cultural exchanges between former adversaries and the youth on both sides who yearned for and ultimately created a pathway out of ethno-nationalism (one which is now at risk). The lessons from this historical and cultural moment are as relevant today as they were six decades ago, and Sneeringer’s elegant and erudite exegesis into these histories stands as an important intervention into larger discussions on the lessons of the past and the shape of a world to come.

Justin Patch is Assistant Professor of music at Vassar College, where he teaches global and popular music traditions. His research focuses on sound and emotion in contemporary US political campaigns and has appeared in Soundings, The European Legacy, The Journal of Sonic Studies, Americana, The Ethnomusicology Review, American Music, and The Journal of Popular Music Studies. His book Discordant Democracy: Noise, Affect, Populism and the Presidential Campaign, which analyzes the 2008 and 2016 campaigns, was published by Routledge in 2019.

A Social History of Early Rock ‘N’ Roll in Germany: Hamburg from Burlesque to the Beatles, 1956-1969

By Julia Sneeringer

Publisher: Bloomsbury Academic

Hardcover / 289 Pages / 2018

9781350034389

Published on October 13, 2020.