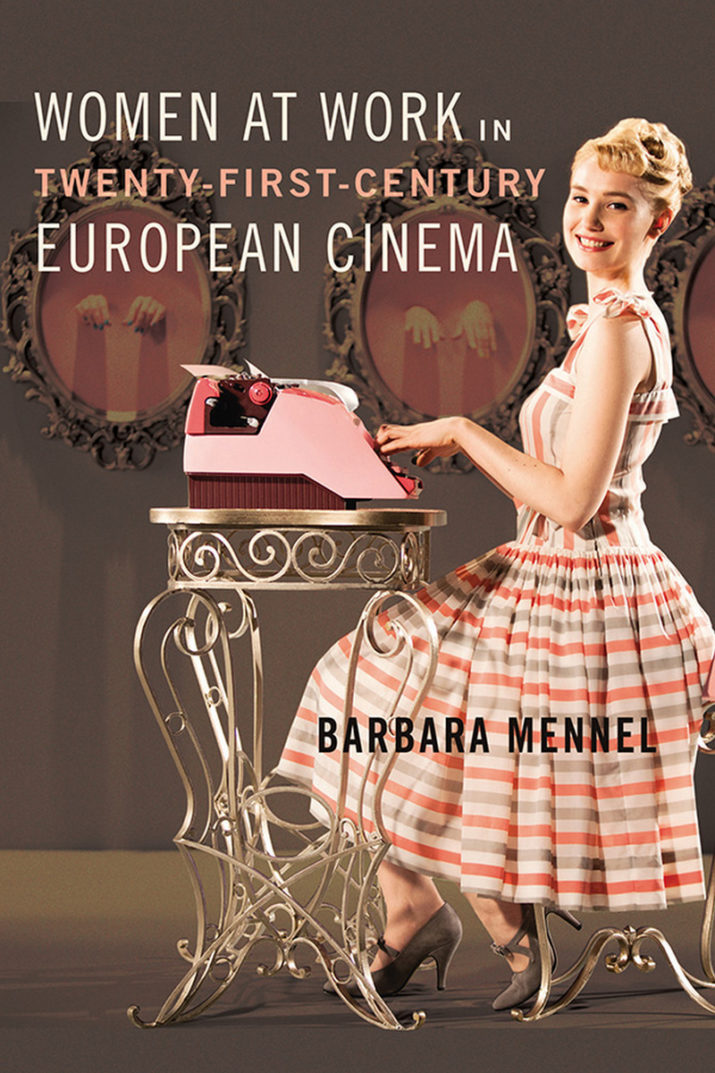

Women at Work in Twenty-First-Century European Cinema, published by University of Illinois Press, is a timely contribution to feminist social theory and film studies. Barbara Mennel’s interesting and, at times, demanding book charts the developments of women in the workforce as depicted in contemporary cinema to reveal the tensions between “feminist advances and their capitalist appropriation.” (2) The book offers what Mennel calls “a cinema of women’s work,” (2) with new readings of several European films made between 2001 and 2016, and provides several frameworks for reconsidering women’s work as it appears in these films. Generically, the scope is broad, encompassing mainstream and art house films, genre cinema, such as romantic comedy, action, and thriller, as well as documentaries and political films and the so-called “weird wave” films, which emerged in Greece, Spain and Portugal following the European economic crisis of 2008. It is of interest to feminist scholars, film scholars, and scholars working across fields including sociology, economics, and critical theory.

Women at Work in Twenty-First-Century European Cinema, published by University of Illinois Press, is a timely contribution to feminist social theory and film studies. Barbara Mennel’s interesting and, at times, demanding book charts the developments of women in the workforce as depicted in contemporary cinema to reveal the tensions between “feminist advances and their capitalist appropriation.” (2) The book offers what Mennel calls “a cinema of women’s work,” (2) with new readings of several European films made between 2001 and 2016, and provides several frameworks for reconsidering women’s work as it appears in these films. Generically, the scope is broad, encompassing mainstream and art house films, genre cinema, such as romantic comedy, action, and thriller, as well as documentaries and political films and the so-called “weird wave” films, which emerged in Greece, Spain and Portugal following the European economic crisis of 2008. It is of interest to feminist scholars, film scholars, and scholars working across fields including sociology, economics, and critical theory.

The book opens with a broad definition of what constitutes “women’s work” in the films discussed. This ranges from waged labor to managerial roles and self-employment, to domestic and reproductive labor, including housework and motherhood. Mennel points out that her discussion of work is not necessarily framed in Marxist terms (although class, along with race and ethnicity, is a key factor in her considerations), couching her argument instead in terms of a materialist feminism, which combines theory with concrete representations. Importantly, Mennel points out in the introduction that although this is essentially a book about women and women’s work, she does not adopt the essentialist assumption that only women can meaningfully convey women’s experiences of work and that only a woman director can make a progressive film about women in the workforce. Thus, films made by both women and men are examined. She also argues that with the continuing appropriation and commodification of social movements by capitalism, there needs to be some critical discourse around this appropriation itself, while at the same time acknowledging the ongoing critical purchase of feminism as a movement. What is at stake in this book is not women’s labor as such, but rather the image of this labor as mediated through film, and how this mediation contributes to the cultural imagination surrounding women’s work and the rethinking of tropes such as the male breadwinner and the housewife.

Mennel provides a careful overview of the different academic debates she engages in, including the connection between work and film (the depiction of material vs immaterial labor, film’s relationship to capitalism, and the historical focus on the male worker in European cinema), the situation of European cinema after the fall of the Berlin Wall (a shift in what constitutes a “European” film), and the rise of the gendered economy in Europe. Mennel then sets the scene for what is a nuanced and multifaceted argument, which treads a very careful path between feminism as a critical discourse and “feminism” as “the handmaiden of neoliberalism,” (6) to quote Nancy Fraser. Mennel comes down on the side of the former (against Fraser) arguing that feminist theory continues to offer “an alternative to the totalizing account of neoliberalism” (25), particularly when considering the role of gender, race, and class in the organization of labor.

Central to the overall argument is Hannah Arendt’s critical distinction between public work and private labor, which becomes in many ways the leitmotif for the book. Important for Mennel is the way Arendt both “maps the binary of gender” onto work and labor (27) and provides a critique of Marx’s theory of labor, which offers the potential to reconceptualize women’s work (particularly in the domestic sphere) outside a strictly capitalist framework. The tradition of excluding this kind of work from analyses of labor is mirrored in contemporary cinema, which, as Mennel points out, “rarely focusses on housewives” (32). There are, however, exceptions, as Chapter One demonstrates, such as Jan Troell’s Everlasting Moments(2008), which depicts a photographer who is also a stay-at-home mother, contrasting the “drudgery” of domestic labor with artistic labor; and Aida Begić’s low-budget Snow(2008), which shifts the focus to the unpaid domestic labor of women working communally immediately after the Bosnian war. While these are obscure films, this chapter also includes a discussion of the better-known Biutiful(2010) by internationally-renowned director Alejandro González Iñárritu, a film which, according to Mennel, deals with the problematic concept of maternity as innate by juxtaposing the “caring” figure of a migrant woman from the Global South with “the domestic failure of the European woman” (42). Indeed, maternal “failure” is a theme which runs through the chapter and seems to be a common, almost symptomatic feature of what Mennel calls “progressive” films about women’s labor.

Chapter Two moves away from domestic and maternal labor to consider women’s place in the labor market of the post-industrial West. Here, Mennel shifts the focus from the notion of working-class solidarity to “solitary female figures who struggle under conditions of post-Fordism and neoliberalism” (53). The chapter begins with a discussion of two key films which emphasize this shift, Ken Loach’s It’s a Free World(2007) and the Dardenne brothers’ Two Days, One Night(2014) with a focus on the precarious situation of labor under neoliberalism. The question raised here is, what is particular about women’s situations in this universality of precarity? Chapter Three examines the “new heritage cinema of industrial and mechanical labour” (78), tracing “the revision of the depiction of factory labour projected into the past and organised around female characters” (79). Several films are discussed, including Régis Ronsard’s 2012 Populaire, which not only taps into the present nostalgia for typewriters but also “claims anachronistic mechanical work for a faux feminism” (102). Topics covered in the remaining chapters include women’s work and migration, material and immaterial labor from factory work through to the care industry, reproductive labor and biotechnology, and the “return of the housewife” (186) in times of economic crisis. Films discussed include Women on the Sixth Floor(Le Guay 2010), Dirty Pretty Things(Frears 2002), Never Let Me Go(Romanek 2010), and Yorgos Lanthimos’ Dogtooth(2009). Of these, the chapter on reproductive labor is particularly interesting as it demands a more nuanced argument to separate what is ostensibly a cross-gender issue (in the films as well as in life): organ harvesting and cloning. Here Mennel draws resourcefully on Foucault’s concept of biopolitics and Giorgio Agamben’s notion of “bare life,”’ noting however that neither concept addresses “gender and reproductive labour” (157). In her reading of Dirty Pretty Things, Mennel squares the circle by claiming (following Donna Dickenson) that “‘we all have female bodies now’ because all bodies may be harvested” (165).

Women at Workcovers a lot of ground, its disparate pathways held together by a commitment to demonstrating the particularity of women’s work in an increasingly global context. This is not just a book about women at work, nor is it just about cinema. It is, rather, an attempt to bring feminist discourse to bear on neoliberalism using films as case studies. This works, on the whole, although there are times when the relevance of feminism to certain social phenomena (such as migration, organ harvesting, and precarious labor) seems open to debate. The burden of the book is to demonstrate that there is no such thing as a post-gender neoliberal subject. The films generally bear this out well; although there are occasions where the lead character appears to be only incidentally female, or where the experiences depicted in the films are shown to be more universal than particular. In one sense, the fate of Sandra (Marion Cotillard) in Two Days, One Nightmight appear quite distinct from her gender (is this not the fate of many workers irrespective of whether they are men or women?). This is perhaps the only tension running through the book: there might be a difference between a film in which the central character is a working woman, and a film which deals with working women’s issues. This tension is perhaps the result of an irresolvable contradiction between feminism and neoliberalism, between the particular and the universal. Mennel’s book intensifies rather than resolves this contradiction and that, is its key strength.

Reviewed by Felicity Chaplin, Monash University

Women at Work in Twenty-First-Century European Cinema

By Barbara Mennel

Paperback / 258 pages / 2019

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

ISBN: 978-0-252-08395-2