A special feature on forced migration, Narration on the Move.

Narration can have a powerful effect on the experience of being on the move away from one’s home; it can aid in trauma recovery, protect collective memory, and serve as an important vector for political agency. Precisely because narrative is such a powerful tool, however, it can also be a treacherous one. The most dangerous narratives about migration can be persuasive even when they are inaccurate. For instance, even though migration to Europe has halved in the last two-years, xenophobic politicians such as Victor Orban, Marine Le Pen, and the recently deposed Matteo Salvini deploy tropes of rising existential threat.[1] These stories about migration are not restricted to the political fringes. When the incoming president of the European Commission announced a new position, the “vice-president for protecting the European way of life,” it became clear that a fictional threat (to a fictionally unitary “way of life”) could nevertheless be written into the structure and priorities of European institutions.[2]

Fortunately, there are countervailing, migrant-authored narratives that offer a more inclusive picture. Projects like My Escape/Meine Flucht, a documentary about the perilous voyage to Germany assembled entirely from the migrants’ own smartphone footage, demonstrate the impact of migrant-authored narratives. Meanwhile, self-determination movements like the Gilets Noirs in France are re-writing the role that migrants, and particularly undocumented migrants, play in public life, elaborating upon the “multidimensional conception of political belonging” developed by earlier sans-papiers activists.[3] The response is not limited to Europe. In the United States, particularly in the Southwest, undocumented people have rallied around the cause of mobility and the freedom to live border-crossing lives, rather than formal membership in a nation-state through citizenship papers.[4] In the Zaatari camp in Jordan, refugees trained in GIS mapping participate in a process akin to city-planning, contributing to decisions about emergency planning and infrastructure.[5] Everywhere, activists, artists, and scholars are mobilizing to debunk pernicious myths about forced migration and to write new stories.

The voices and experiences of migrants themselves should be the foundation of this effort to change the narrative about forced migration. As Lisa Malkii cautioned, even well-intentioned humanitarian discourse can fall into the trap of representing forced migrants as “mute victims” rather than historical actors.[6] We can draw inspiration from the profusion of new narratives bucking those stereotypes. In film, literature, and photography, in contemporary therapeutic contexts, and in our historical archives, there are examples of cliché-defying stories about forced migration forged from migrants’ experiences, imagination, and commitments. In this special issue, Narration on the Move, we highlight the way that students, researchers, educators, and artists are collaboratively producing new narratives about migration.

A migrant-centered understanding of migration can have sweeping implications for public discourse. Giovanna Faleschini Lerner illuminates the use of the video camera as a discursive tool in the hands of migrant mothers. She studies the film Ibi, constructed in Italy out of footage from the home videos of the eponymous author-subject alongside footage filmed after her death. She explores the stories that Ibi, a migrant mother, tells her children from across an ocean, and argues that the film is part of a migrant memory archive that tells a truer story than the mainstream notions of migration and security politics which it seeks to subvert.

A sense of control over one’s narrative and life can be elusive but powerful for people experiencing displacement. In their joint article, Evan Henritze and Adam Brown argue for “collective self-efficacy” as a new framework for mental health interventions that accounts for the political dimensions of displacement. Although the community’s political power may be circumscribed, developing a common belief—a shared narrative—about the collective ability to cope with hardship and to enact change can have salutary mental health effects.

It is imperative to respect migrant communities’ collective understandings of themselves for scholars who are not migrants but who create works of literature, art, and scholarship based on migrants’ experiences to listen carefully to migrants before attempting to synthesize or theorize. When done right, informed representations of migration can be equally impactful for migrants and non-migrants. Eva Woods Peiró taught her bilingual “Building Inclusive Communities with Latinx Poughkeepsie” course to prompt students to hold reflective conversations with Latinx Poughkeepsie residents and understand residents’ concerns about issues including migration. The course centered language, asking students to work towards nonhierarchical relationships based on an understanding of both parties’ goals and priorities in English and/or Spanish. Tracey Holland has produced remarkable collaborative projects and research using a listen-first model in her “I Learn America” project. She pairs college students with high school students who have recently migrated to the United States in support of migrant students’ autobiographical storytelling projects. The projects educate college students while helping migrant students to feel control over the way their stories are told.

Matthew Brill-Carlat also addresses the question of how colleges can support high school students with a forced migration background, reflecting on the inaugural year of Vassar’s “New Americans” Summer Program, which eighteen migrant high school students attended. Brill-Carlat expands the definition of college access beyond the simple question of space, and is clear-eyed about historical barriers to equal access. Filmmaker Jan Müller’s short documentary about the program, weaving migrant student interviews with professional footage, serves as an example of how the arts can serve as a vehicle for shaping new narratives on the basis of migrant knowledges.

One of the “New Americans” classes taught Jérôme Ruillier’s graphic novel The Strange (2018), which spins a narrative of migration and political disenfranchisement, chronicling the life of an unnamed migrant in a Western country (with clear allusions to France) and the people who help or hinder his activities. The characters are drawn fancifully but the exhaustive research — including interviews with migrants, police officers, and nonprofit staffers — and analysis of Europe’s contemporary migration policies builds a product that resonated with the students enrolled in the summer program.The featured interview with Ruillier includes questions from “New Americans” students, in addition to Brittany Murray. Ruillier speaks candidly about the writing process, migrant rights, what it means to be a “strange” in every sense of the term, and our obligation to hospitality.

Research processes as exacting as Ruillier’s must be learned and practiced. This summer, Adam Brown led a research trip to Bern, Switzerland for graduate and undergraduate students at the member campuses of the Consortium on Forced Migration, Displacement, and Education (CFMDE). Brown and his students’ research points to the need to develop mental health interventions for displaced people that train non-specialists to support their own communities’ wellbeing, and they evaluate this model’s record and promise in Switzerland. Task-shifting is one way that knowledge about mental health can be transferred from a small handful of experts to a broader community of migrants and supporters. The program helped undergraduate students develop the technical and ethical sensibilities necessary for conducting research on migration before they must choose a specialized area of graduate study or a career in government, NGOs, or non-profits. Furthermore, the task-shifting approach calls for mental health practitioners to have broader training that includes the humanities, social sciences, and languages.

The narratives we tell ourselves—or forget, or ignore—about universities’ ethical commitments to the idea of refuge in the past can have direct effects on universities’ responses to forced migration today. The institution of the university has been a source of new ideas that integrate policy proposals with humanist commitments for centuries. Nancy Bisaha writes that the early European university could be considered a “movable refuge” for scholars and students alike. An interview with Arien Mack shows a contemporary expression of the university as refuge, exploring how she drew on 20th century precedents of universities being places of refuge to develop an initiative to help displaced scholars. The history of the University in Exile, which extricated scholars from Nazi-occupied lands and brought them to the U.S., inspired her to found the New University in Exile Consortium in response to the current, increasing persecution of academics and crackdowns on academic freedom across the globe.

In the Commentary section, noted American photographer, journalist, and writer Amy Kaslow’s photo-essay on forced migration and mental health, titled Life After War: Disturbed, traces displacement across the globe, from the Kosovo War, sexual violence and conflict in Syria, and gang violence in Central America. Her narrative is an injunction to reconsider the role that liberal arts play in bringing together the respective strengths of the humanities, sciences, and social sciences. In this vein, Kaslow, the Consortium on Forced Migration, Displacement, and Education, and EuropeNow are proud to announce a groundbreaking digital resource that will go live in the coming weeks. Kaslow’s stunning photo essay will form the cornerstone of EuropeNow’s new Digital Classroom, a web-based archive devoted to innovative teaching materials.

Stefanie Woodard’s syllabus for her “Moving Histories” course, featured in the “Campus” section, is a model of how universities can incubate global thinking. Through a European lens, and with complementary sources from around the globe, “Moving Histories” asks students to think historically and critically about contemporary migration and how it is typically described in the news and conversation. Blending theory, case studies, and community engaged learning, Woodard’s “Moving Histories” syllabus and accompanying reflection on the process of building the course, is an instructive example for anyone looking to bolster migration studies and critical engagement with the past and present. Miles Rodriguez teaches a class called “Migrants and Refugees in the Americas: Understanding Mexican, Central American, and Global Migration to the United States” that examines migration to the U.S., and the discourses around migration, in the twentieth and early twenty-first century. Each course has its area of focus, but the syllabi are committed to the same broad intellectual questions, pointing to the need to share knowledge across specialties and to understand migration outside a regional or area studies approach.

This issue’s “Campus Spotlight” section highlights Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. In this section we feature the work of Vassar students and professors who are pursuing a wide array of research, community-based, and artistic projects around forced migration. In addition to Holland’s article on the “I Learn America” project, we present student contributions on the mental health effects of displacement, the intersection of migration and disability, and how displaced people collectively narrate their identities to the outside world. The section also features a collective article on the innovative organization Conversations Unbound (CU), written by its founding director (a Vassar graduate) and two professors who have worked with CU, on how the organization helps universities disrupt hierarchies of knowledge that devalue refugees as thinkers and knowledge producers.

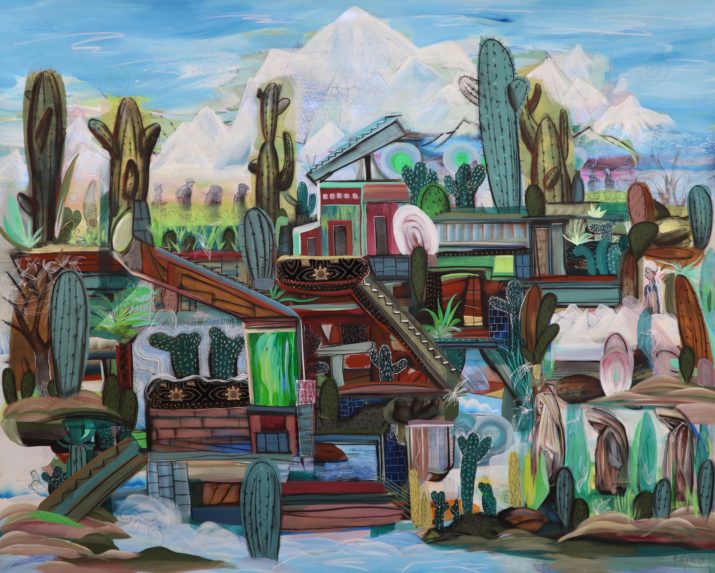

The featured artist for this issue is Charles Geiger, whose “quasibotanical” paintings dwell on climate change and forced displacement across the globe. Deeply concerned with the natural world, Geiger’s rich colors and striking landscapes depict settings both arid and tropical, where encroachments of gangs and armies, or rising tides and strengthening storms, push people from their homes.

Together, these contributions indicate new ways to narrate forced migration, rooted in past actions of hospitality while remaining responsive to contemporary challenges. As these contributions demonstrate, the call to build sustainable models of defying borders is at the same time a call to rethink academic categories. Europeanists are finding new contexts for their work; as we approach the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin wall, new walls are being erected in the U.S., in Hungary, and Saudi Arabia. It has never been more vital to share knowledge across domains, and it has never been more urgent to forge connections between research and pedagogy. The writers in this issue traverse academic disciplines, challenging the traditional relationship between researcher and subject and re-writing the roles of student, teacher, artist, and educator. On both sides of the Atlantic, European and North American scholars are benefiting from transnational exchange to change the stories we tell about global migration.

Research

-

“Archives of Migrant Motherhood: Andrea Segre’s ‘Ibi’” by Giovanna Faleschini Lerner

-

“The Medieval University as Refuge” by Nancy Bisaha

-

“Translating Socio-Cognitive Models of Agency into Migration and Mental Health: A Framework for individual and Community Empowerment” by Adam Brown and Evan Henritze

-

“From the Couch to the Community: The Emergence of Peer-to-Peer Therapy for Refugees in Switzerland” by Adam Brown

Commentary

Interviews

-

“Committing to Academic Sanctuary: An Interview with Dr. Arien Mack” by Matthew Brill-Carlat

-

Campus interview: “Foreign, Strange, Singular, Exceptional: An Interview with Jérôme Ruillier” by Brittany Murray

Visual Art

Campus Spotlight: Vassar College

-

“Displaced Students and Higher Education Access: Reflections from Vassar College” by Matthew Brill-Carlat

-

New Americans Summer Program at Vassar College by Jan Müller

-

“Resignation Syndrome: A New Conversation” by Ava McElhon Yates

-

“Book Review Essay: Narrating Refugee Identities” by Desmond Curran

Brittany Murray is a scholar of French & Francophone Studies who teaches forced migration at Vassar College. Her first book project was Taking French Feminism to the Streets: Fadela Amara and the Rise of Ni Putes Ni Soumises, and she is working on a book about the 1970s, a decade of economic upheaval, changing gender roles, and new migration policy in France. She is also the Program Coordinator for the Consortium on Forced Migration. Displacement, and Education.

Matthew Brill-Carlat is the Coordinator of Research and Pedagogy with the Consortium on Forced Migration, Displacement, and Education. He is a recent graduate of Vassar College, where he majored in History. Born and raised in Baltimore, MD, Matthew lives in Poughkeepsie, NY.

References:

Europarl, “Asylum and migration in the EU: facts and figures,” European Parliament, July 22, 2019. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20170629STO78630/asylum-and-migration-in-the-eu-facts-and-figures

Fernández, Luis, and Joel Olson. “The Freedom to Live, Love, and Work Anywhere You Please: Arizona and the Struggle for Locomotion.” Contemporary Political Theory, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Aug., 2011).

Malkii, Lisa H. “Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization,” Cultural Anthropology. Vol. 11, No. 3 (Aug., 1996).

McNevin, Anne. “Political Belonging in a Neoliberal Era: The Struggle of the Sans-Papiers.” Citizenship Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2 (May 2006).

Tomaszewski, Brian, Jean-Laurent Martin, and Yusuf Hamad. “GIS for Refugees, by Refugees.” Esri.com, Summer 2017. https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcnews/gis-for-refugees-by-refugees/

Trilling, Daniel. “‘Protecting the European way of life’ from migrants is a gift to the far right.” The Guardian, September 13, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/sep/13/protecting-europe-migrants-far-right-eu-nationalism

[1] Europarl, “Asylum and migration in the EU: facts and figures,” European Parliament, July 22, 2019. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20170629STO78630/asylum-and-migration-in-the-eu-facts-and-figures

[2] Daniel Trilling, “‘Protecting the European way of life’ from migrants is a gift to the far right,” The Guardian, September 13, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/sep/13/protecting-europe-migrants-far-right-eu-nationalism

[3] Anne McNevin, “Political Belonging in a Neoliberal Era: The Struggle of the Sans-Papiers,” Citizenship Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2 (May 2006), 131-151.

[4] Luis Fernández, and Joel Olson, “The Freedom to Live, Love, and Work Anywhere You Please: Arizona and the Struggle for Locomotion,” Contemporary Political Theory, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Aug., 2011), 4-6.

[5] Brian Tomaszewski, Jean-Laurent Martin, Yusuf Hamad, “GIS for Refugees, by Refugees,” Esri.com, Summer 2017. https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcnews/gis-for-refugees-by-refugees/

[6] Lisa H. Malkii, “Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization,” Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 11, No. 3 (Aug., 1996), 378.

Photo: Charles Geiger

Published on October 22, 2019.