This is part of our special feature on forced migration, Narration on the Move.

With the rise of western modernity and the invention of childhood, the job description of parenthood has expanded to include the establishment and maintenance of childhood archives.[1] A baby’s first shoes, teddy bear, or pacifier, are safely archived in boxes in a parent’s attic or basement. Baby books, which encourage parents to record milestones such as their children’s first tooth, first word, or first steps, are available both in paper and digital forms; social media platforms offer opportunities to create and disseminate the contents of these archives openly across time and space. If the archive is “the means by which historical knowledge and forms of remembrance are accumulated, stored and recovered,”[2] as Charles Merewether writes, the existence of these familial archives asserts the importance of childhood in one’s biography. But how different are the experiences of those parents and children who are separated because of migration? What kind of parenting do migrant parents perform from afar? What kind of memory archive do they build for their children? And what role can cinema play in preserving and disseminating these archives of migrant memories? In this article, I examine these questions in their gendered dimension by considering the case of Andrea Segre’s documentary film Ibi (2017), which focuses on the story of Ibitocho Sehounbiatou, a woman from Benin who left her three children in the care of her mother in order to seek work in Italy.

Produced by ZaLab in 2017 for Jolefilm and RAI Cinema, in collaboration with Open Society Foundations, the film explores long-distance motherhood as an important facet of the feminization of migration, which has become a major concern in migration studies. While scholars and experts acknowledge that women have always participated in internal as well as cross-border migration movements, they have observed that increasing numbers of women are migrating independently. Moreover, women’s migration is different from men’s in relation to both circumstances and opportunities. The feminization of migration has thus generated an increased awareness of the gendered types of labor that migrant women perform in host countries, their economic importance within their home societies as remittance senders, their changing roles within their families and communities, including the phenomenon of so-called “mobility orphans.”[3]

Segre’s Ibi offers important insights into the experience of women migrants from West Africa, thanks partly to the director’s decision to combine Matteo Calore’s contemporary photography with the protagonist’s own home videos. The film is thus almost entirely based on Ibi’s self-narration as an immigrant woman, describing her own life in Europe through a series of video letters to her children, which allow viewers to gain an insider’s perspective on the experience of migrant motherhood.[4] From an esthetic and narrative point of view, the film represents a paradigm shift in its approach to telling stories of migration. Though collectives like ZaLab have been consistently using participatory practices of filmmaking to give space to marginalized experiences within Italian society,[5] Ibi expands the notion of participatory filmmaking to include found footage and its potential for the creation of “a fluid archive,” whose meaning remains unstable and shifting.[6] In the landscape of migration cinema in Italy the film distinguishes itself in three interweaving ways: as a documentary source that allows us to understand the specificity of migrant mothers’ experiences within the context of the feminization of migration, as an example of ZaLab filmmakers’ continued engagement with innovation in film language and narrative, and finally as participating in the aesthetic of the archive.[7]

Ibi’s migration journey is steeped in specific geographies. Born in Benin in 1960, she spent a few years as a migrant worker in the Ivory Coast before deciding to leave for Italy in 2000. In order to pay for her passage to Europe, she agreed to carry a certain quantity of drugs from Nigeria into Italy. When she landed at the Naples airport she was immediately intercepted, tried and convicted. She then spent three years in prison before her good behavior and the support of local social workers resulted in the commutation of her sentence to house arrest. Without a home in Italy, she spent some time in a halfway house managed by the Comboni Missionaries in Castel Volturno. It was there that she met Salami Taiwo Olayiwola (Alaho), an immigrant from Nigeria, and decided to move in with him. Castel Volturno is the home of the largest African diasporic community in Italy. It was the object of Guido Lombardi’s 2011 fiction film, Là bas. Educazione criminale (Là bas. A Criminal Education), which explored the tensions with the local camorra clans that exploded in the massacre of Castel Volturno in 2008, where several innocent immigrants of Ghanaian, Liberian, and Togolese nationality were killed. As in Là bas, in Ibi the filmmakers put on display the diversity of this community, with its linguistic and religious plurality. Within Ibi’s own household, Salami is anglophone and Ibi is francophone, but they communicate in Yoruba—a language spoken primarily in Nigeria and Benin, with an estimated 80 million speakers worldwide. Salami appears to be an observant Muslim, and Ibi is deeply religious, but she does not wear a headscarf or veil and is clearly an emancipated woman, challenging without fanfare our received notions of Islam and gender roles in Muslim societies.

Separated from her children and her mother in Benin, with no hope of returning without risking permanent deportation, Ibi starts recording and documenting her life in Italy early on through photography and videography. Subsequently, as a professional photographer and videographer, she records important events—weddings, christenings, and other celebrations—in the various African communities in Castel Volturno, whether Muslim, Catholic, or Protestant.

The opening sequence immediately establishes Ibi as the focalizer and narrator of the film: she is present through her voice, but remains invisible among the people she interviews, because—as she explicitly states—she is the one who is doing the filming (Figure 1). At this point, a coworker takes over the filming so that she can enter the frame and speak directly into the camera [Figure 2]. Ibi thus claims for herself the authorial position, which she reasserts throughout the film through moments of meta-reflectivity on her job as a photographer and videographer.

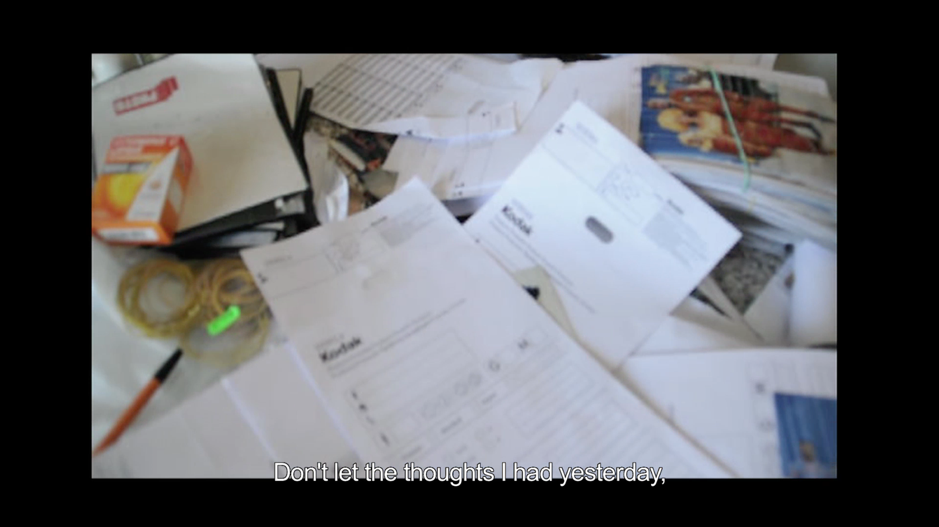

Some of the footage included in the film comes from Ibi’s experimentation with camera filters and lighting. An entire sequence is devoted to a prayer recited over her photographs, which are represented as a means of providing for her family. A high angle shot shows bags of photos and proofs sitting on the floor before the camera moves to a table covered in additional prints, while Ibi’s voice offers a prayer that God may bring prosperity both to her and her clients, so that she will be able to send remittances over to her children (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Screen Capture from Ibi. Image by Ibitocho Sehounbiatou. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale Zalab.

Figure 1. Screen Capture from Ibi. Image by Ibitocho Sehounbiatou. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale Zalab.

Figure 2. Screen Capture from Ibi. Image by Ibitocho Sehounbiatou. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale Zalab.

Figure 3. Screen Capture from Ibi. Image by Ibitocho Sehounbiatou. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale Zalab.

Photography plays a central role in Ibi’s life and in her film in ways that reflect its importance in the so-called “technologies of care”- that connect migrant mothers to their children in their home countries. In a study of Gambian parents in the United Kingdom, Pamela Kea describes these technologies as essential to the construction and maintenance of the “affective circuits” that envelop migrant parents, caregivers, and children, and that include the “flows of goods, money, information, love, and advice.”[8] Within these affective circuits, she argues, photographs work as stages on which the performance of parenting can take place. In Ibi’s photographs, this performative function is highlighted by a non-realist approach to portraiture, which allows the person portrayed to display their self-fashioning as a successful, happy individual, often on a background that has nothing to do with their actual location, or even by photoshopping absent family members into a picture that commemorates a family milestone such as a baptism or a wedding (Figure 4). Photographs, then, become “agentive objects”[9] that produce knowledge and meaning in ways that conform to the expectation for parental care and involvement in their children’s lives, even from a distance. Indeed, as Kea writes, the “expectations of intergenerational care” are often what motivates transnational migration in the first place.[10]

Figure 4. Photomontage by Ibitocho Sehounbiatou. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale Zalab.

If, for the most part, her clients use photographs, Ibi’s preferred technology of care is videography. Her mother and children are the intended audience of most of her videos, which are in fact meant as video letters through which she is able to send messages of love and hope to her family back home and to share her daily experiences with them. In many of these home videos, recorded through a fixed camera perched on a tripod, Ibi puts herself literally at the center of the frame, speaking about her life in the first person. She focuses on her own presence, her maternal body, as though to remind her children of her contemporary, embodied, maternal existence. In many sequences she enters and exits the frame while performing quotidian tasks such as cleaning, hanging laundry out to dry, or planting and watering vegetables in her garden, thus displaying for her family the routine activities that punctuate her life in Italy (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Screen Capture from Ibi. Image by Ibitocho Sehounbiatou. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale ZaLab.

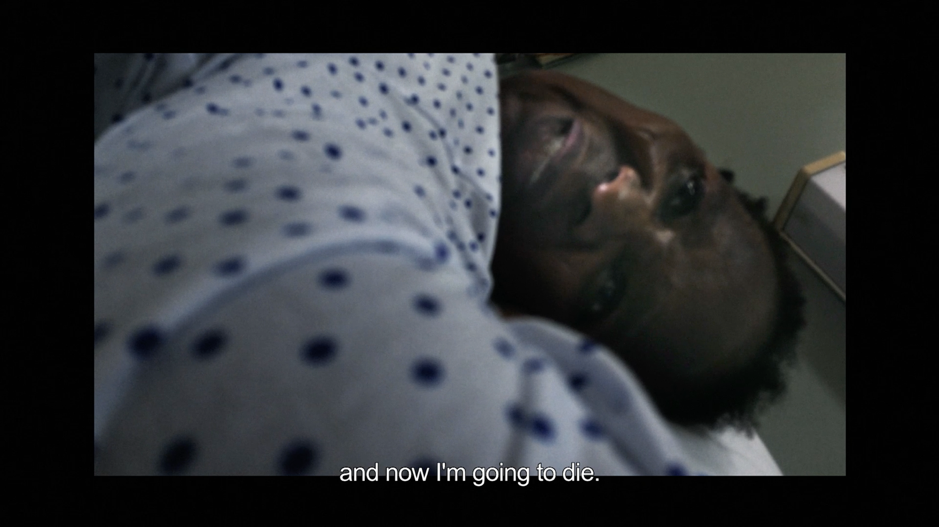

In these videos she is most often seen smiling and laughing and represents herself in positive and upbeat tones, as a person who is full of productive ideas—like planting vegetables in the barren garden of her house—and initiatives—such as the photography business she establishes. She often takes the opportunity to address concrete concerns expressed in phone calls by her children—mostly requests for financial help. She is grateful, after her years in prison without the ability to communicate outside its walls, for the ways in which technology allows her to re-establish a connection with her family. But she also often appears blurred, both as a result of her errors in setting the focus and as a metaphor for the way that memory is blurred by distance and slowly dissolves. Her blurred face is particularly poignant in her very last message to her family, filmed from her hospital bed shortly before her death from cancer in 2015 (Figure 6).[11]

Figure 6. Screen Capture from Ibi. Image by Ibitocho Sehounbiatou. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale Zalab.

In another important sequence, the mood is constantly shifting precisely because of the ways in which Ibi evokes and engages with her distant family. Initially, Ibi films and jokes around with Salami and a friend while they are plastering and repainting the walls of their house (Figure 7). She remains outside the frame, and asks them questions in Italian, encouraging them to speak the language of their new country. Ibi’s real purpose, though, is to “explain Europe” to her sons in Benin—she thus turns the camera onto herself and starts explaining how she feels about being in Italy: she begins by acknowledging human weakness and powerlessness in relation to God; she then observes how fast time moves while being away from one’s family and she expresses the fear of deportation that belongs to all undocumented migrants, contrasting it with the joy of receiving residency papers—as her husband and his cousin did (Figure 8). For Ibi, receiving papers is the equivalent of a miracle, which only God can grant as a reward for a good heart—a miracle, in her case, that would enable her to see her mother and her sons again after years of separation.

Figure 7. Screen Capture from Ibi. Image by Ibitocho Sehounbiatou. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale Zalab.

Figure 8. Screen Capture from Ibi. Image by Ibitocho Sehounbiatou. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale Zalab.

In this sequence, Ibi reveals migration to be both a translocal and a transtemporal experience.[12] Time is plural in so far as it moves differently in Castel Volturno than it does at home in Benin.[13] As Pierre Bourdieu points out, “control of time is critical to the production of inequality,”[14] and Ibi is subject to the time of Italian state bureaucracy while her request for asylum is slowly processed, rejected, and eventually—posthumously—granted. Thus Ibi experiences diasporic time as both slower and faster than in her home country—faster in so far as her children’s growth and development continue in her absence, and especially when she was in prison and was unable to fulfill her role in their chain of care, either toward them or toward her mother; slower because her situation as an undocumented migrant cannot be quickly resolved.

Place is also plural for the migrant. Ibi’s distance from her children strengthens her sense of dislocation. She pines for a native home that occupies a semi-mythical place in her migrant imaginary.[15] But she also attempts to build a home for herself in Castel Volturno, as we have just seen. For Ibi and Salami, the idea of home is also connected to the possibility of cultivating the land and growing produce—a desire that is constantly frustrated by the exorbitant rents landowners require of foreign migrants. The agricultural dimension of home is both concrete and metaphorical and fits in with a gendered approach to diasporic conceptualization. Robin Cohen distinguishes between a patriarchal, Judeo-Christian view of diaspora as the scattering of male seed and a more feminine set of arboreal metaphors—roots, family trees, and soil.[16] He suggests that however rigid these gendered oppositions might seem, the feminine metaphors help complicate views of diaspora as victimization rather than as a dynamic interdependence between rooted subjectivity and global identity.[17] For Ibi, the rootedness comes from her civic engagement with the Movimento Migranti e Rifugiati di Caserta (Caserta Movement for Migrants and Refugees), of which she becomes a leader. Her death leaves a hole in the closely knitted human relationships that constituted her home in Castel Volturno, as well as in the house that she shared with Salami. And in fact, Matteo Calore’s camera displays and explores the void that her absence has left behind in Salami’s house (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Screen Capture from Ibi. Courtesy of Associazione Culturale Zalab.

Calore’s photography also echoes Ibi’s framing and composition in her videos. He too tends to use a fixed camera and let human figures drop in and out of the frame. In this respect, his and Segre’s work on Ibi is representative of ZaLab’s approach to documentary filmmaking as a form of productive, participatory collaboration between documentarists and their subjects. Since the collective’s establishment in 2006, ZaLab has produced a significant number of documentaries and participatory videos workshops in Italy and elsewhere, empowering marginalized communities to tell their own stories. Calore’s and Segre’s choice to adopt Ibi’s aesthetics in order to integrate her past experiences within a perspective from the present derives from Zalab’s ethos of participatory creativity, which reasserts Ibi’s own creative agency in much of the original footage she produced. Perhaps inevitably within the Ibi project, however, a tension develops between the filmmakers’ ethical drive and the actual use of Ibi’s found footage.

In film theory, found footage is defined in its broadest sense as “any images made for occasions other than the ones in which it is used.”[18] Though they use found footage to preserve the memory of Ibi’s life, the filmmakers have access to it only because of her death and her loss of control over this material, which they appropriate and reinterpret in the absence of her authorial agency. To a certain extent, then, their film contradicts Ibi’s narrative authority at the same time that it highlights it and thus foregrounds the difficulties inherent in the ZaLab artistic project tout court. On the other hand, giving Ibi’s images a platform, Segre and Calore allow her films to tell an alternative story about undocumented migration and about African women’s roles both in relation to their families at home and within their diasporic communities. In this respect, it is possible to interpret Ibi as a form of archive.

The archive as an institution is inextricably connected to power and implicated in imperialistic practices and politics of colonization.[19] Projects of decolonization such as Segre’s and Calore’s film must therefore subvert and re-appropriate the archive. Segre’s directorial work, from the documentary Come un uomo sulla terra (As a Man on Earth, 2008) to the fiction film L’ordine delle cose (The Order of Things, 2017), has consistently aimed at disturbing mainstream constructs of migration. In Come un uomo sulla terra, Segre worked with Dag Yimer and Riccardo Biadene to create a repository of migrant stories that complicated the Italian government’s accounts of its security agreement with Libya. Segre’s film thus contributed to the project of Asinitas Onlus/Archivio Memorie Migranti (Archive of Migrant Memories) in Rome, which co-produced it together with Zalab.[20] The Archivio Memorie Migranti is an archive in so far as it gathers, organizes, and makes public individual stories of migration; it includes migrants’ memories and also contributes to constructing migrating memories—collective memories in motion, in constant transformation. The guiding principle of the Archivio is participatory collaboration between researchers and migrants who are actively involved in the coproduction of oral and written narratives that are then collected, archived, and publicly distributed. The ethical and political project of the archive is to transform the public’s view of transnational migration from a foreign, alien experience to a “shared collective patrimony.”[21] Through the posthumous documentary dedicated to her memory, Ibi, too, contributes to the construction of the migrant memory archive in her own voice and through her own images. Ibi’s struggle as a migrant mother separated from her family, an asylum seeker caught in bureaucratic limbo, an African woman in a racially prejudiced country, is not forgotten but on the contrary given space and time through the archeological un-layering of her visual memories and words in the film that bears her name.

By making Ibi’s video material available to the public, rather than keeping it confined to the private sphere of her family, Segre contributes to the decolonization and “democratization”—to use Jacques Derrida’s term—of the migrant archive.[22] He makes it available not simply by granting unrestricted access to the film audience, but by making it legible through an ongoing dialogue between the present of Ibi’s videos and the memories of her that they elicit in the people that loved her, particularly her husband. Ibi thus allows us to understand the archive as a living object which should not be buried as belonging to the past, but engaged in a conversation with the present. It is within this dialogue that Ibi’s archive helps unveil the power dynamics that underlie current debates on migration and political responses to it.

Giovanna Faleschini Lerner is Associate Professor of Italian at Franklin & Marshall College. She is the author of Carlo Levi’s Visual Poetics: The Painter as Writer (Palgrave Macmillan 2012) and the co-editor of Italian Motherhood on Screen (Springer 2017). She has been guest co-editor of Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies and gender/sexuality/Italy, and has published numerous articles on twentieth- and twentieth-first-century Italian literature and cinema. She is currently at work on a monograph on Italian cinema about migration.

References:

Appadurai, Arjun. “Archivio Pubblico, Migrazioni e Capacità di Aspirare.” Meridiana 86 (2016): 9–19.

Ardizzoni, Michela. “Narratives of Change, Images for Change: Contemporary Social Documentaries in Italy.” Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies 1.3 (2013): 311–26.

Ariès, Philippe. Centuries of Childhood : A Social History of Family Life. New York: Vintage Books, 1965.

Brah, Avtar. Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities. Gender, Racism, Ethnicity Series. London: Routledge, 1996.

Braester, Yomi. “The City as Found Footage: The Reassemblage of Chinese Urban Space.” In Global Cinematic Cities: New Landscapes of Film and Media, edited by Johan Andersson and Lawrence Webb, 157-77. New York; Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Braidotti, Rosi. Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

Caritas Internationalis. “The Female Face of Migration.” Background paper. 2010. <<www.caritas.org/includes/pdf/backgroundmigration.pdf>>. (Accessed January 15, 2019).

Coe, Cati. “Orchestrating Care in Time: Ghanaian Migrant Women, Family, and Reciprocity.” American Anthropologist118 (2016): 37-48.

Cohen, Robin. Global Diasporas: An Introduction. Seattle: Washington UP, 1997.

Come un uomo sulla terra. Directed by Andrea Segre, Dag Yimer, and Riccardo Biadene. Italy: ZaLab, 2008.

De León, Jason. The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema II: The Time-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. London: Continuum, 2005.

Derrida, Jacques. “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression.” Translated by Eric Prenowitz. Diacritics 25.2 (1995): 9-63.

Faleschini Lerner, Giovanna. “Liquid Maternity in Italian Migration Cinema.” In Italian Motherhood on Screen, edited by Giovanna Faleschini Lerner and Maria Elena D’Amelio, 211-232. New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Fass, Paula, ed. The Routledge History of Childhood in the Western World. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Frisina, Annalisa and Stefania Muresu. “Ten Years of Participatory Cinema As a Form of Political Solidarity with Refugees in Italy: From Zalab and Archivio Memorie Migranti to 4caniperstrada.” Arts 7.4 (2018). <<https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040101>>. (Accessed August 22, 2019).

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Graves-Brown, Paul, Rodney Harrison, and Angela Piccini, eds. Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Contemporary World. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013.

Heywood, Colin. A History of Childhood: Children and Childhood in the West from Medieval to Modern Times. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018.

Ibi. Directed by Andrea Segre. Italy: Jolefilm, Open Society Foundations, RaiCinema, and Zalab, 2017. Streaming.

Kea, Pamela. “Photography and Technologies of Care: Migrants in Britain and their Children in Gambia.” In Affective Circuits: African Migrations to Europe and the Pursuit of Social Regeneration, edited by Jennifer Cole and Christian Coe, 78-100. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2017.

Là bas. Educazione criminale. Directed by Guido Lombardi. Italy: Minerva, 2011. DVD.

L’ordine delle cose. Directed by Andrea Segre. Italy, France: JoleFilm, MACT, RaiCinema 2017. DVD.

Luiselli, Valeria. Lost Children Archive: A Novel. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

Merewether, Charles. “Introduction: Art and the Archive.” In The Archive, edited by Charles Merewether, 10-17. London: Whitechapel; Cambridge: MIT P, 2006.

Reynolds, Rachel. “ ‘Bless This Little Time We Stayed Here’: Prayers of Invocation as Mediation of Immigrant Experience among Nigerians in Chicago.” In Ethnolinguistic Chicago: Language and Literacy in the City’s Neighborhoods, edited by Marcia Farr, 161–187. Mahwah: Erlbaum, 2004.

Rich, Adrienne. Blood, Bread, and Poetry. London: Women’s Press, 1986.

Triulzi, Alessandro. “Per un archivio delle memorie migranti.” N.d. <<www.archiviomemoriemigranti.net/archivio-delle-memorie-migranti/ricerche/per-un-archivio-delle-memorie-migranti/>>. (Accessed August 22, 2019).

[1] The scholarship on childhood as a modern concept is abundant. Perhaps the most influential—if now outdated—study of the history of childhood is Philippe Ariès’ Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life (New York: Vintage Books, 1965)). More recently, the essays edited by Paula Fass in The Routledge History of Childhood in the Western World (New York: Routledge, 2012) and Colin Heywood’s A History of Childhood: Children and Childhood in the West from Medieval to Modern Times (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018) have helped complicate and refine Ariès’ analysis.

[2] Charles Merewether, “Introduction: Art and the Archive,” in The Archive, ed. Charles Merewether (London: Whitechapel; Cambridge: MIT P, 2006), 10.

[3] Caritas Internationalis, “The Female Face of Migration,” 2010, 2, <<www.caritas.org/includes/pdf/backgroundmigration.pdf>> (accessed January 15, 2019).

[4] Migrant mothers do not often appear in major roles in Italian films focused on the migratory experience; for a discussion of some films where motherhood is a central preoccupation, see Giovanna Faleschini Lerner, “Liquid Maternity in Italian Migration Cinema,” in Italian Motherhood on Screen, eds. Giovanna Faleschini Lerner and Maria Elena D’Amelio (New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 211-232.

[5] On the Zalab experience, see Michela Ardizzoni, “Narratives of Change, Images for Change: Contemporary Social Documentaries in Italy,” Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies 1.3 (2013): 311–26; and Annalisa Frisina and Stefania Muresu, “Ten Years of Participatory Cinema As a Form of Political Solidarity with Refugees in Italy: From Zalab and Archivio Memorie Migranti to 4caniperstrada,” Arts 7.4 (2018), ´<<https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040101>> (accessed August 22, 2019).

[6] Yomi Braester, “The City as Found Footage: The Reassemblage of Chinese Urban Space,” in Global Cinematic Cities: New Landscapes of Film and Media, eds. Johan Andersson and Lawrence Webb (New York; Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press, 2016) 158.

[7] My approach is informed by a post-structuralist perspective and engages with migration and diaspora studies, post-colonial studies, and women’s and gender studies.

[8] Pamela Kea, “Photography and Technologies of Care: Migrants in Britain and their Children in Gambia,” in Affective Circuits: African Migrations to Europe and the Pursuit of Social Regeneration, eds. Jennifer Cole and Christian Coe (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2017) 79.

[9] Kea, “Photography and Technologies of Care,” 81.

[10] Kea, “Photography and Technologies of Care,” 79.

[11] It is important to note that Ibi’s suffering does not occupy much space in the narrative economy of the film, in a way that asserts Ibi’s inexhaustible vitality.

[12] Cati Coe, “Orchestrating Care in Time: Ghanaian Migrant Women, Family, and Reciprocity,” American Anthropologist 118 (2016): 38.

[13] Rachel Reynolds, “ ‘Bless This Little Time We Stayed Here’: Prayers of Invocation as Mediation of Immigrant Experience among Nigerians in Chicago,” in Ethnolinguistic Chicago: Language and Literacy in the City’s Neighborhoods, ed. Marcia Farr ( Mahwah: Erlbaum, 2004), 175-77.

[14] Coe, “Orchestrating Care in Time,” 38.

[15] Avtar Brah, Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities, Gender, Racism, Ethnicity Series (London: Routledge, 1996).

[16] Robin Cohen, Global Diasporas: An Introduction, (Seattle: Washington UP, 1997), 177.

[17] Cohen, Global Diasporas, 177-178.

[18] Braester, “The City as Found Footage,” 157.

[19] See Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972) and Arjun Appadurai, “Archivio Pubblico, Migrazioni e Capacità di Aspirare.” Meridiana 86 (2016): 9-19.

[20] Founded in 2005, Asinitas is an educational not-for-profit organization based in Rome. Its mission is to promote the inclusion of migrants, asylum seekers, and other marginalized individuals in Italian society through education and social work.

[21] Alessandro Triulzi, “Per un archivio delle memorie migranti,” n.d., <<www.archiviomemoriemigranti.net/archivio-delle-memorie-migranti/ricerche/per-un-archivio-delle-memorie-migranti/>> (accessed August 22, 2019).

[22] Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” trans. Eric Prenowitz, Diacritics 25.2 (1995): 11.

Photo: Continuous one line drawing. Family concept. Mother walking with small children | Shutterstock

Published on October 29, 2019.