This is part of our Campus Spotlight on Bard College Berlin.

Inspired by the title of this journal, a group of international students enrolled in “A Lexicon of Migration” at Bard College Berlin responded visually and in writing to the question: what is Europe now? In the weeks leading up to the assignment, we discussed the meanings and workings of colonialism, borders, migration, and belonging in Europe and beyond. We have read, among others, Doreen Massey’s 1991 essay “A Global Sense of Place,” excerpts from Walter Rodney’s 1972 How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, and Nicholas De Genova’s introduction to a recent volume titled The Borders of “Europe” and the European Question (2017). We were also fortunate to host two wonderful guest speakers on our campus: Matthew Gandy (University of Cambridge), who showed and discussed with the audience his 2017 documentary film Natura Urbana: The Brachen of Berlin, and Prem Kumar Rajaram (Central European University), who delivered a lecture titled “Border Crisis?: Governing Human Mobility in Europe and Beyond.”

Four weeks into the semester, students were encouraged to engage critically with the readings we discussed in class so far and draw from their own experiences in and of Europe to respond to the question. Below are several representative examples of their work.

—Agata Lisiak for EuropeNow

“A Sense of Europe” by May Keren

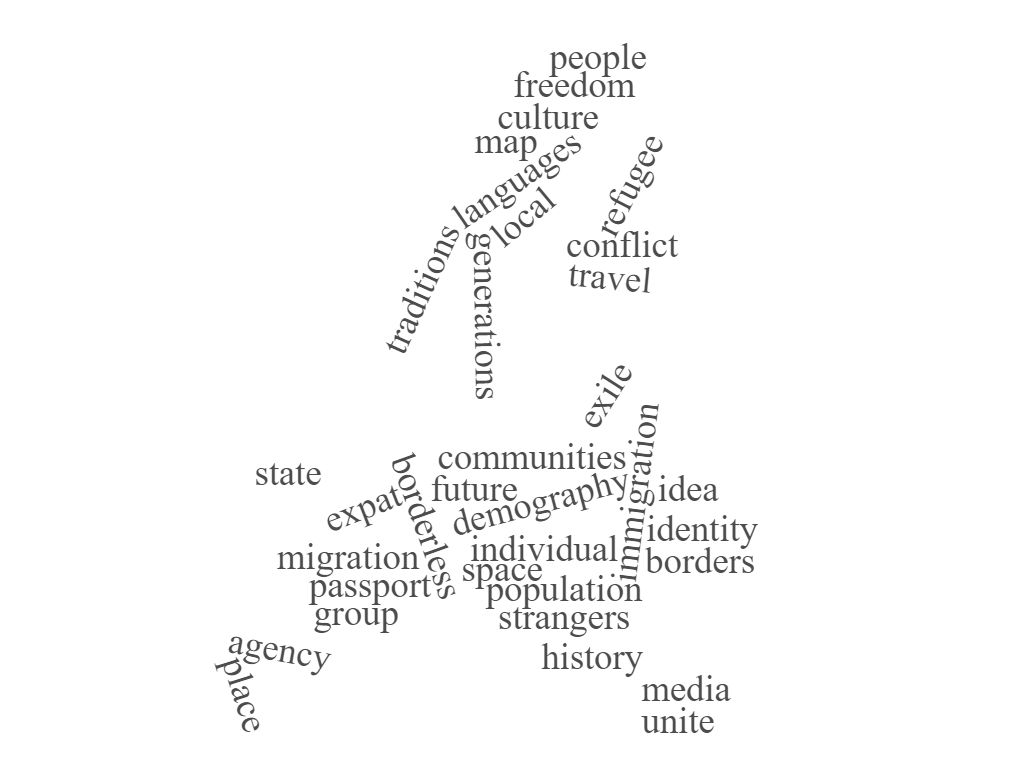

Europe as a term holds diverse definitions for different people and groups. Throughout history, the understanding and shape of Europe changed multiple times due to diverse desires to dominate over its space. Thinking of Europe in contemporary times raises ideas of cultural diversity, borders regimes, economic inequalities, and the core notions of unity and identity. Who is included in Europe and who stands outside of it? Is Europe a continent or is it synonymous with the European Union? Does living in Europe make someone European? What does being a European even mean? At the heart of all these questions are two issues – unification and identification – and both relate to borders and people’s aspiration for a sense of place.

The above picture of “Europe” is composed as a lexicon of words that reflect the main ideas behind the issues of unity and identity and concern both Europeans and “outsiders”. Each word in the lexicon echoes the diverse possibilities for definitions and meanings of contemporary Europe. By using words to delineate a map of Europe, the borders and places are being fragmented and dissolved. It is not clear what is being outlined, but according to the website wordcloud.com, in which it was made, this is the shape of Europe. Significantly, there is no hierarchy between the words and they are arbitrarily scattered to “fit” the shape of Europe’s map.

When thinking about the borders of Europe as its delineation, it is unclear what exactly is considered to be (in) Europe, which countries are included on the map and which are not. As Massey asserts in “A Global Sense of Place”: “Geographers have long been exercised by the problem of defining regions, and this question of ‘definition’ has almost always been reduced to the issue of drawing lines around a place” (152). By creating the word map without delineated borders around countries, the idea that places should not be reduced to a lineated map is emphasized. Although borders reflect the social concern for a definition, the word map of Europe changes this notion by eliminating the borders and, at the same time, creating a map that represents the diverse ideas of and perspectives on Europe. The word map connects the notions of unity and identity, as the need to unify Europe into a concrete portrait is being questioned by how Europe should be defined. The places that are chosen to be in a map represent the people who identify with these places, hence borders divide not only the places but the people as well. Although the borders of Europe provide a territorial definition, they do not take into consideration the varied ideas that people have in mind when identifying with Europe. The bordering of a place encloses it to be a place of an inside and an outside, of fragmented areas and becomes a tool to separate and dissociate people from one another. Borders disable the notions of unity and inclusive identity with regard to people’s sense of place.

It is the notion of diversity and the acceptance of the “other” under the same desire for unity and identity that may unify people under a progressive definition of Europe. The word map of Europe enables this unification by creating an inclusive borderless definition. The lexicon of words represents ideas, concepts, and questions that open the borders for change; it is not bounded to delineated borders. In the search for elements that unite and identify what Europe is and who is European, the borderless definition of Europe proposes what Europe could be.

May Keren is an Ethics and Politics student at Bard College Berlin, from Israel.

“The Reappropriation of Space: What is Europe Now?” by Jude Macannuco

This photograph depicts an industrial building on Schwedenstraße in Berlin-Wedding. Owned by the Gewerbesiedlungs-Gesellschaft (GSG Berlin), which was formally operated by the Berlin government before being taken over by the private company Orco Property Group, this structure was originally a factory of the AEG-Telefunken, a company which produced radio devices and transmitters. Constructed between 1939 and 1942, the building held a strategic function as a site of military technology production for the German Wehrmacht during the Second World War (Elfert). In the fifties, single story extensions were added to the building and served as production depots for vehicles (GSG Berlin). The AEG-Telefunken decided to abandon the building in the eighties. It has since been renovated and repurposed by the GSG, transforming into an office space where companies and start-ups that define themselves as “creative” and “innovative” can rent out spaces for their operations. Its industrial architecture highlights the building’s multifaceted political and socioeconomic history in its usages, while also underlining broader economic, political, and social shifts that have characterized Western Europe during the building’s history.

Doreen Massey’s theorization of space and place provides insight into this building’s evolution both in relation to its immediate urban environment and to global economic shifts. Massey writes that places are constituted through “a particular constellation of social relations, meeting and weaving together at a particular locus” (154). Places are, thus, “absolutely not static” (155). The industrial utility and functions of the building have been altered, though it remains a site of labor, the nature of this labor draws attention to the general shifts that have taken place in Western Europe in the post-industrial era, namely the shift from a Fordist economy dominated by standardized, extremely specialized labor to a knowledge economy focused on entrepreneurship and innovation. We can, then, perceive this building as simultaneously housing new configurations of labor while recalling an era dominated by a different kind of labor. The building is also one of many loci where gentrification processes are taking place: rising property values are transforming working-class, immigrant neighborhoods such as Wedding into trendy, and therefore costly, living and working spaces.

Massey stresses the importance of any particular place’s global linkage with other places. She writes that “there are real relations with real content … between any local place and the wider world in which it is set” (155). Indeed, in viewing this building through a historical lens, one must also consider the imperial and Nazi legacies that brought it into being and the processes that engendered the transformations of its utility. Walter Rodney describes the exploitative activities of European colonizers in Africa and the West Indies, poignantly demonstrating that “African contribution to European capitalist growth extended over such vital sectors as shipping, insurance, the formation of companies, capitalist agriculture, technology, and the manufacture of machinery” (97). Europe, in reaping the wealth that it forcefully extracted from Africa and elsewhere, was able to “develop” itself through the production of machinery and new technologies, which required vast sums of wealth. This building, thus, emblematizes and carries within it this extracted wealth, and the brutal colonial legacy that accompanies it. This historical connection could be viewed as indirect; indeed, Germany had lost its African colonies after the First World War, so this building’s emergence did not coincide with Germany’s colonial regime. However, as Rodney insists, Europe’s wealth is based on the exploitation of Africa in manifold, also indirect ways, a truth that persisted even in the aftermath of Europe’s cessation of “direct” colonization. Rodney’s analysis elucidates the global relations that made this building possible.

The GSG building illuminates both historical and contemporary truths about Europe, and locates the role of Europe’s historical political actions within Europe’s contemporary economic life.

Jude Macannuco is a student of Ethics and Politics at Bard College Berlin in Berlin, Germany. His interests include migration studies and urban sociology.

“Layers of History and Temporary Homes” by Omar Haidari

Historical bonds in Europe are as varied as the threads in a piece of fabric. I will attempt to give an answer to the short but dense question “What is Europe” by pointing out a few aspects from which we can view Europe. The photographs above are taken from a short 1 minute 40 seconds video I shot at the Tempelhof Airport, Berlin. One can see remnants of decades-old texts (US Army) on the walls of the airport as well as more recent billboards advertising German language courses for refugees aimed at better integrating them into society. The billboards, architecture, and the texts on the wall symbolize a multitude of historical events.

Primarily, I will define Europe from a migrant’s point of view. I recorded the short video at the Tempelhof Airport, which has been turned into an emergency shelter for refugees. The history of this airport and its transformation into a refugee shelter are controversial. Tempelhof Airport was reconstructed from a small airfield by the Nazis in the 1930s. Its design and size were a massive portrayal of Hitler’s vision, as well as a representation of Germany’s racial primacy through its architecture. Tempelhof’s current presence is a living history of various eras: it was a laboratory for the world’s best aircraft, used as an airlift for medicine and food in response to the Soviet Union’s blockade in 1948-49, and it also witnessed the endpoint of Hitler’s power. The historical significance of this place imposes extreme living restrictions for refugees. As a result of its historical and national importance, and it being listed as a historical landmark, refugees are obliged to make this fascist architecture their home and are not allowed to bring any revision to the construction of this building to make it more livable.

Tempelhof was/is a “tempo-home”, or temporary home, for me and thousands of other refugees. This airport, as a refugee shelter, always made me feel that this place is temporary since the airport is a temporary place for people who are coming and going, who are arriving and departing. Tempelhof’s history and it being an airport always reminded me of my temporal and unknown existence there, as well as in Germany. The lack of privacy, constant loud noises in each hangar, and twelve beds in 25 m² blocks stress and traumatize people–especially when they have run away from a conflict zone.

While I was in the Tempelhof emergency shelter, I always wondered whether the other refugees and I were being protected from the outside world by being placed in this extremely restricted living space. On the other hand, I also wondered whether placing us in this space was another way of alienating us and keeping the outside world safe from refugees. With the passing of each hour in the hangar filled with small containers with 8-12 beds each, I felt indeed contained and wondered whether the government was trying to render us invisible to those on the outside. The architecture (alongside the environment and nature) has a direct impact on shaping people’s lives. It is people who design architecture and it is (other) people who are, in turn, shaped by it.

During his lecture at Bard College Berlin, Prem Kumar Rajaram (Central European University) pointed out the ways in which architecture can shape lives and boundaries – and not just physical boundaries, but also boundaries in people’s minds. The architecture of the great Tempelhof Airport was a symbol demonstrating Hitler’s power and dominance in Europe and the world. At the present moment, this architecture has unintentionally and ironically fulfilled the Nazis’ beliefs regarding racial supremacy by making hundreds of people live and adjust their lives in this airport which traumatizes, stresses and depresses any person’s well-being.

Omar Haidari is an Ethics and Politics student at Bard College Berlin. He has been involved in volunteer work helping refugees over the course of the past two years in Berlin. As he is pursuing his BA degree, he is conducting research focusing on migration, migration in Germany, as well as the history of Afghan migration to Germany.

“Inclusion Through Exclusion: Europe’s Complicity in Global Inequalities” by Wilma Ewerhart

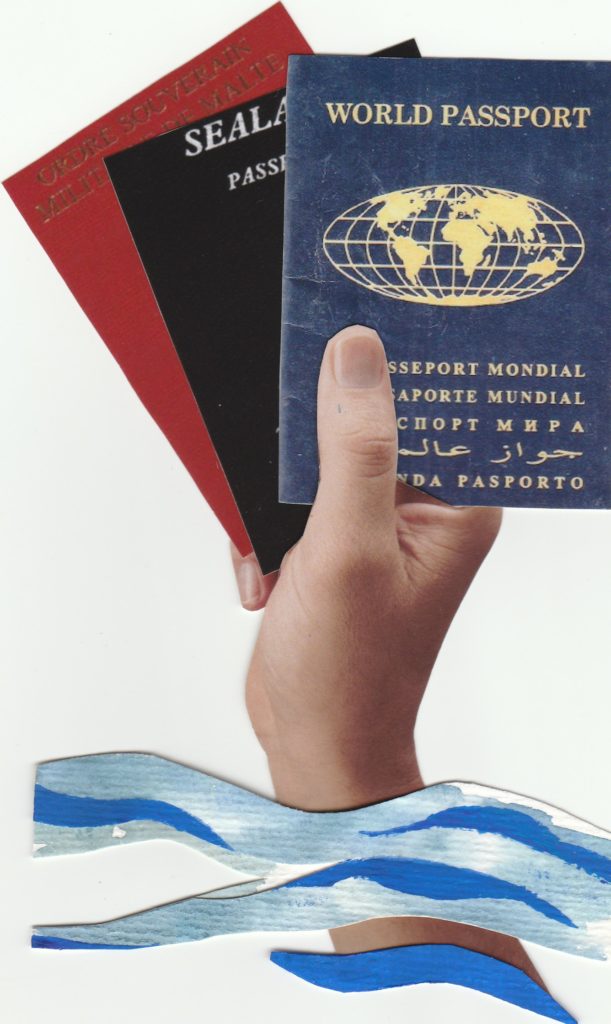

The small collage I created depicts a hand emerging from troubled water, holding a small stack of several nations’ passports as if they were playing cards. One of the nations, Sealand, is a so called “micronation” – a state that is both tiny and very contested in territorial and political terms. Sealand is well known for being a sort of eyesore to the United Kingdom both literally and metaphorically, given that it is nothing but an oil rig some seven nautical miles from its shores. It has drawn much attention – and thus debate – about what actually constitutes a state and what values states, particularly European states, should exemplify. Sealand highlights the banal reality of the state, the immense privilege associated with belonging to a certain place over another, but also the commonplace lack of agency one has with regard to where one comes from and what one is consequently allowed to do: travel, exist in certain spaces, learn, migrate.

What is often labelled Europe’s ‘”igration crisis” in European media “has long been nowhere more extravagantly put on display than in the Mediterranean Sea … The European Union has actively converted the Mediterranean into a mass grave” (De Genova 3). Nicholas De Genova describes the atrocities of bordering in Europe and the effect it has on those who are kept out by the practice. By contrast, Sealand’s motto, E Mare Libertas (From the Sea, freedom), an easily realized utopic fantasy given Sealand’s size and brief history of 52 years, sees the sea as providing safety and freedom. Repurposing an ex-Naval Sea Fort for the territory of a new utopia, as Sealand does, subverts the idea of bordering and reappropriates territory from the UK, a state complacent in the harmful practices of “redrawing the colonial boundary between a European space largely reserved ‘for Europeans only’ and the postcolonial harvest of centuries of European exploitation and subjugation” (De Genova 18).

The second passport in the collage is that of The Sovereign Military Order of Malta, a European Christian organisation with no territory, yet a usable passport. It has active diplomatic relations with 107 states, permanent observer status at the United Nations, and a population of two. What does Europe stand to gain from its relationship to The Sovereign Military Order of Malta, and what makes the presence of “other”, non-European actors so undesirable by comparison? All personhood is aimed to be erased at the level of what states try to make simply bureaucracy; yet, as Doreen Massey put it, “some people are more in charge of [mobility] than others; some initiate flows and movement, others don’t; some are more on the receiving-end than others, some are effectively imprisoned by it […] Mobility, and control over mobility, both reflects and reinforces power” (149). In Europe, a place which touts itself as progressive and is very much proud of its provisions of internal mobility to EU citizens, the lack of care towards those who are refused their right to pass through the borders of Europe is harshly felt.

Most important in this collage is the passport at the front, the World Passport, issued by the World Government of World Citizens after the ideals of Garry Davis, an ex-US citizen who renounced US citizenship in 1948 and subsequently declared himself a citizen of the world. The World Passport breaks that final utopic barrier, past Sealand’s ideas of parodying the European state, towards highlighting the very banality of restricting human movement, making the passport both a highly political tool and one devoid of all significance and function. Perhaps the World Passport presents an opportunity to re-invent an all-encompassing understanding of Europe that does not deny its history of migration and spatial subjugation. Because even an increasing inward freedom of those holding EU citizenships (in form of the Schengen Agreement, for example) is felt all the more by rampant nationalisms within Europe wanting to redraw internal boundaries or fortify outward ones to decrease the likelihood of outsiders coming in. The ever-growing supranational entity of Europe still exists against the backdrop of “the other”: those not belonging and thus suffering under the regulations aimed to keep them out.

Wilma Ewerhart is a student in the BA Humanities, the Arts and Social Thought Program at Bard College Berlin. Wilma is set to graduate this Spring.

“Europe Then and Now: How About the Future?” by Mohamad Othman

Europe now and Europe then? Who hasn’t heard of Europe or wasn’t influenced by it? Between the fifteenth and twentieth century, despite making up only 8 percent of global landmass, Europe conquered, colonized and controlled over 80 percent of the globe. It drew borders and divided communities, claiming cultures and resources for itself, and implementing its own laws with no regard for the locals in the areas under control. Some such stolen goods are now inseparable from the “European” identity. Things that are now considered “originally” European were brought from other parts of the world, becoming part of national images by which European states are now known. Is tea British, for example? Does Britain even grow tea? No, it is just a saying. Britain claimed its colonies as part of the British Empire until the people of those colonies came to Britain and tried to “enjoy being British” and assimilate into a culture to which they already felt they belonged.

To borrow Stuart Hall’s words, describing his own take on the matter:

People like me who came to England in the 1950s have been there for centuries; symbolically, we have been there for centuries. I was coming home. I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea. I am the sweet tooth, the sugar plantations that rotted generations of English children’s teeth. (48)

By talking about being there symbolically for centuries, Hall argues against a belonging based solely on physical location. For centuries, those under the rule of the British Empire were allowed to belong so long as they did not step outside the bounds of symbolic belonging. Hall made the justified argument that although tea leaves and sugar for the tea are understood as British, he himself is more British than the person drinking the tea. However, in reality it appears that to be British means to be the person disconnected from the processes of colonization that have given them the privileged position to merely “enjoy” the final product.

The years that followed the kinds of interactions detailed in Stuart Hall’s experiences show a side of the “other” and how a person coming from the “European” colonies could never become truly European: one would always be seen as inferior and unwelcome, only belonging in the limited and symbolic sense. A person could come to Europe and claim the right to stay, using Europe’s own laws, and still one of the responses a person receives is an invitation to return “voluntarily”, owing to the continued egotistical need of Europe to maintain its position of power and dominance.

One poster from the Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat (translated officially, if not exactly faithfully, into English as Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community) in Germany is written in languages other than German, and is an invitation for people coming as refugees and migrants to go back. It targets specific nationalities, as seen in the flags on the poster, demonstrating that there is a specific group of people who are especially unwelcome. Furthermore, there is an incentive to take the deal: a full year’s payment by the German government. One of the arguments used to attack migrants is that they are economic migrants weakening the economy; here the government will pay them to go back if they take the deal, which is ironic. The web domain itself (returningfromgermany.de) shows that the emphasis is not on going home and the German government helping the returners to build a life for themselves, but rather the focus is on gettting away from Germany. This shows the primacy of the nation and national interest over and above humanitarian issues: the very avoidance of advertizing the policy as “Returning to Nigeria” (for example) points to a repressed awareness in the German consciousness that this return is ultimately to the benefit of Germany and the detriment of the prospective returner.

Mohamad Othman is an Economics and Politics student at Bard College Berlin.

Funding for the development of this version of A Lexicon of Migration came from the Center for Civic Engagement at Bard College and the Mellon-funded Consortium on Forced Migration, Displacement, and Education.

References

De Genova, Nicholas, ed. The Borders of” Europe”: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering. Duke University Press, 2017.

Elfert, Eberhard. “U-Bhf Osloer Str.: Stadtplanung Einer Unwirtlichen Kreuzung » Weddingweiser.” Weddingweiser, 22 Mar. 2017, weddingweiser.de/2012/10/25/u-bhf-osloer-str-stadtplanung-einer-unwirtlichen-kreuzung/.

GSG Berlin. “Gewerberäume in Berlin-Mitte 2019”: www.gsg.de/de/mieten/gewerbe/berlin/mitte/.

Hall, Stuart. “Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities.” In Culture, Globalization, and the World-System: Contemporary Conditions for the Representation of Identity, edited by King Anthony D. University of Minnesota Press, 1997, 41-68.

Massey, Doreen B. “A Global Sense of Place.” Space, Place, and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009, pp. 146–156.

“Modernisierter Gewerbehof Im Berliner Norden.” GSG-ORCO.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Verso, 2018.

Bard College Berlin is part of the Mellon-Funded Consortium on Forced Migration, Displacement, and Education.

Photo: Europe abstract background with dot connection vector | Shutterstock

Published on April 2, 2019.