Water Stress and Pollution in Belgium: The Internationalization and Regionalization of a Policy Problem

This is part of our special feature on Water in Europe and the World.

2018 has seen the hottest and driest summer in Western Europe since records began. This prolonged heat and dryness has touched areas in England, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France amongst others, affecting farms and forests, threating agricultural output, pasture, and feed supply. In Belgium, drought has highlighted concerns about water stress, pollution, and water resources management that were already in the political agenda. Projections of water availability for the second half of the twenty-first century predict a decrease in water availability for summer and an increase for winter, suggesting drier summers and wetter winters,[1] and putting water at the center of the policy challenges that Belgium will be facing in the coming decades.

In this article, we describe the main features of the country and trace the principal characteristics of water resources in Belgium, identifying the commonalties it shares with neighboring countries, but also the particularities of the country. We evaluate the measures taken for water policy and management, and pinpoint the most pressing institutional and policy issues that Belgium confronts. Belgium is a remarkable case to examine how a small but institutionally complex country has dealt with the challenges of water stress and pollution in a context of simultaneous internationalization and regionalization of water policy.

Belgium

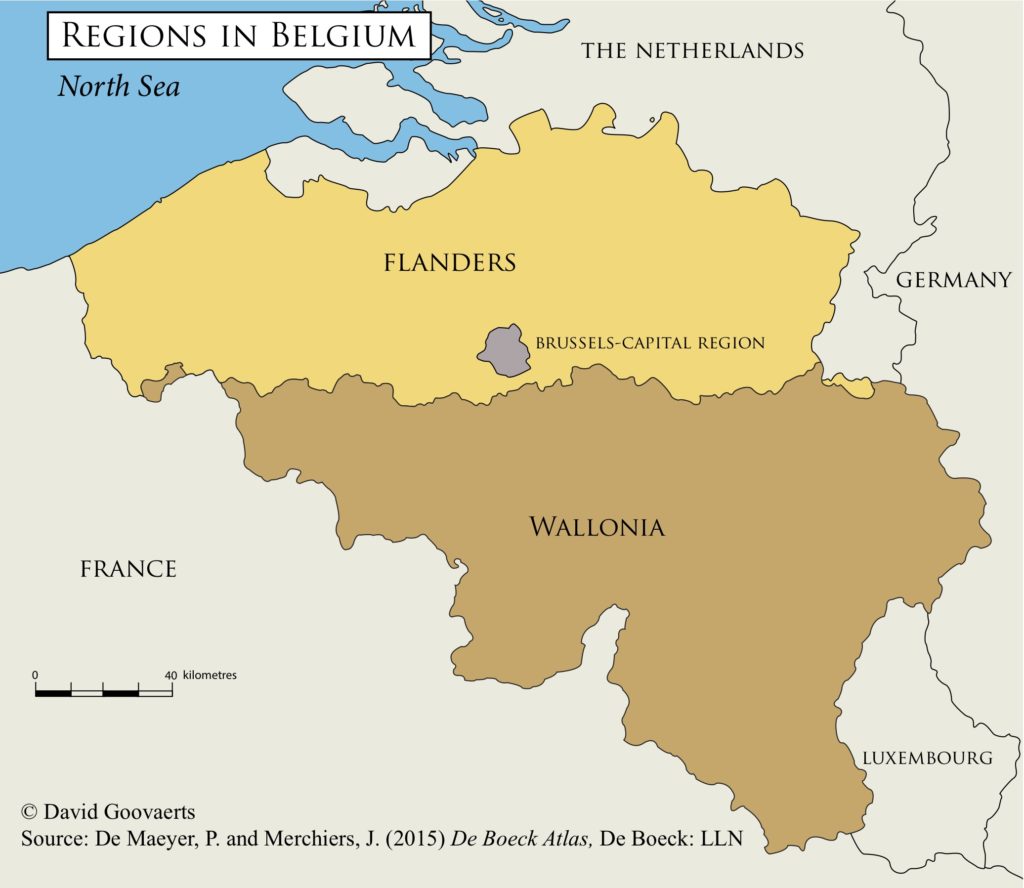

Belgium is a highly industrialized, very dense, and very urban country in Western Europe with a population of around 11 million inhabitants (372 people/km²). It is a constitutional monarchy that shares borders with France, the Netherlands, Germany, and Luxemburg. Since 1993, after a series of constitutional changes in 1970, 1980, and 1988, and in response to internal political tensions, Belgium has been a federal state composed of three regions—Wallonia, Flanders, and Brussels-Capital Region, as well as three Communities: the French Community, the Flemish, and the German speaking Community.

Decision-making power is shared by the Federal Government, the three Communities, and the three Regions (See Map 1). The Federal Government is exclusively responsible for justice, social security, monetary and fiscal affairs, and national defence. The three Communities deal with cultural matters and education. The three Regions have authority in respect of socio-economic matters, such as zoning and planning, housing, agriculture, employment, and energy. The Federal Government and the Regions share competences on the environment—so while the Federal Government is in charge of the protection and management of coastal waters, the Regions define policies for waste, green areas, forests, continental waters, and waterways in their respective regions. Besides this, the local authorities (589 in 2018) are responsible for the provision of local services, which include, among others, the collection, treatment and distribution of drinking water and sewerage within their municipal land.

Although water resources in Belgium are not as scarce as in other countries in Europe— particularly the Mediterranean countries—Belgium is vulnerable mainly as result of its high population density. Annual freshwater availability in Belgium is with 1174 m³ per capita low, which contrasts with 5,393 in the Netherlands, 11,872 in Hungary or the 2,274 m³per capita in Germany.[2] On the other hand, annual water consumption in Belgium is one of the most efficient in Europe. The domestic sector – household and services – annually employs about 26m3 per inhabitant, significantly less than, say, the Netherlands or Germany respectively (55m3 and 46m3 per person). This value has remained remarkably stable in the last ten years despite a significant demographic increase, thanks to the improvement in the state of the pipeline network and the ampler use of water-efficient appliances. As for the Belgian manufacturing industry, it is an important user of water, using about five times as much water as all households. This contrasts with the pattern of use in countries with little industry and/or a strong service sector, such as Luxembourg and Cyprus, where water use for manufacturing amounts to only 5 percent of the total.

Belgium’s water resources are distributed among five main river basins (See Map 2). The Maas and the Scheldt are the largest, originating in France and flowing into the sea in the Netherlands. In addition, the Yser in Flanders and the Oise (tributary of the Seine) and the Moselle (tributary of the Rhine) in Wallonia are smaller and irrigate only around 10 percent of the country before flowing into the North Sea or continuing their courses in France. The use of surface waters is prevalent in Belgium. Indeed, unlike countries such as Denmark or Malta, where the volume of abstracted groundwater is fifteen times as high as the volume of abstracted surface water, in Belgium, 88.5 percent of all abstractions are from surface waters (mostly for the cooling of nuclear power plants) and only 11.5percent from groundwater (2010 data).[3]

The distribution of water resources is very uneven between the north and the south of the country. Wallonia, in the south of Belgium satisfies 55 percent of the national drinking water needs although its population share is only 37 percent. The Region of Brussels imports 66 million m3 from Wallonia as drinking water supply—97 percent of its total needs—while Flanders imports around 40 percent of its demands from Wallonia. Thus, satisfying Brussels’ and Flanders’ water needs depends on resources existing beyond their regional frontiers. Developing governance structures that make this possible in a country with a history of regional tensions has been a crucial element for water policy-making in Belgium—we address this aspect further below.

Water pollution as main environmental challenge

As in any other industrial country, water pollution has been one of the great—if not the greatest—and longstanding environmental challenges facing Belgium.[4] Urban waste water was already identified as a public health concern in the second half of the nineteenth century, when certain large public works—such as the vaulting of the Senne river going through Brussels—were initiated with the aim to limit the impacts of undesirable pollution discharges. However, adequate sanitation was limited to only certain urban areas, while wastewater treatment was nonexisting. After the Second World War, increasing both industrial and agricultural production became key priorities for the economic development of the country, and it was achieved by mechanization, intensification and increased use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. These practices had negative environmental impacts on water bodies —nitrates run-off, industrial metals and organic contaminants—but they received little attention. Timid initiatives were taken in 1950, when a new law on the protection of water was adopted, aiming to ensure a sufficient river flow capable of taking water pollutants to the sea. Also in 1965, a “Royal Commissariat on the Water Problem” proposed a plan to ensure urban wastewater treatment in Belgium, which would be the core of legislative proposals adopted in the early 1970s. These attempts identified water needs and proposed solutions, but for the most part they involved the construction of dams to control river flow and the adoption of measures to ensure quality standards for drinking water, and not about pollution control.

The development of a policy to fight against water pollution in Belgium was started in the early 1970s, matching with initiatives adopted both at the international and the European levels. The meeting of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment and the signing of international treaties and agreements concerning water resources management and pollution control[5] marked the beginning of an international effort to integrate economic activity with an awareness of ecological limits. In the European Union (EU), the first Environment Action Programme and the establishment of a common environmental policy in 1972 sought the harmonization of national pollution policies as a requisite to create a functioning common market. In Belgium, the incipient environmental policy was directed in the early 1970s by the national government. In absence of a Ministry for the Environment, it was the Ministry of Public Health that took the lead in issues related with protecting water quality and the environment, and certain provisions for pollution control were adopted[6]. However, the development of a comprehensive policy to fight against water pollution and to regulate water resources in Belgium came in the following two decades hand in hand with two simultaneous processes: the Europeanization and the regionalization of water policy.

Europeanization of water policy

From the mid-1970s onward, EU environmental legislation increased rapidly. Between 1975 and 2000, 12 water directives were adopted to deal with the negative effects of different sources of pollution in diverse recipient waters. EU directives are compulsory so they cannot be enforced selectively or partially, but give EU member states some leeway to define how they are to be implemented (article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union). EU environmental legislation was initially aimed at creating a level playing field for a common market: by establishing common environmental laws, EU member states wanted to ensure that any costs associated with pollution were assumed entirely by the polluter member state, and not by any other EU country. Progressively, the scope of EU environmental regulation expanded, and so ‘‘pollution control’’ and ‘‘environmental protection’’ became fully-fledged EU policy objectives.[7]

Special mention must be made of the Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for the Community action in the field of water policy (the Water Framework Directive – WFD) adopted in 2000. The WFD has been a fundamental text for the management and the protection of water bodies in Europe. First, it has streamlined the wide diversity of different objectives and requirements that EU water directives established, and set up a common time schedule for implementing their demands. Secondly, the WFD has required EU member states to create new river basins authorities for the management of rivers. By introducing the principle of integrated river basin management, the WFD has sought to ensure the coordinated and integrated planning, development, and use of water resources in Europe. For this, it also asks Member states to produce and update specific and regular “River basin plans,” indicating how they plan to achieve “good status” for all their river basin districts. This requirement entails analyzing the status of the water bodies, a plan of measures to improve their conditions, and a system for monitoring and reporting any progress.

Furthermore, the WFD determines that Member States should “take account of the principle of recovery of the costs of water services,” broadly defined to include the costs of abstraction and distribution of freshwaters and the collection and treatment of wastewater. Member states must ensure that appropriate mechanisms for costing water resources and water services are developed, and also specify how the existing water tariffs will recover the costs of providing water services.[8]

Belgium, a founding member of the EU, has participated in the negotiations of these directives, has transposed them all into national and regional legislation, and has taken measures to implement their requirements.[9] EU law has been, in this sense, an engine for policy change not only with regards to the degree of protection of water bodies, but also on how water policy should happen both in Belgium and in all other EU countries.

Regionalization of water policy

The adoption of EU environmental policy has been simultaneous to the progressive devolution of power from the Belgian State to the Regions. In 1980, the Flemish and Walloon regions were established and were granted the exclusive responsibility for environmental policy in their territories.[10] For Brussels, it took until the state reform of 1988-89, when the region received its own institutions. From then on, the regional governments have decided on the measures they apply within their jurisdictions, in agreement with EU and other international provisions.[11] The regional authorities and the federal government coordinate international environmental policy in a “Comité de coordination de la politique internationale de l’environnement (CCPIE) or Coördinatiecomité Internationaal Milieubeleid.”[12] The committee is organized into working groups; one of them concerns water policy. This committee sets up the position of Belgium at the international and EU levels.

In the exercise of their competencies as environmental regulators, the three regions have operated autonomously. Flanders’s approach has consisted in favoring measures to lessen its dependency on water supply from Wallonia. This has meant a more stringent regulation of pollution discharges and a better control of diffuse pollution, particularly from the 1990s onwards. For this, it created Aquafin, a publicly owned company responsible for the treatment of urban wastewater in the region, and it took definitive steps towards the integrated management of waters in Flanders which resulted in the adoption, in 2003, of the Regional Law on Integrated Water Policy. This law institutionalized the river committees as coordinating body for local authorities.[13] The revision of this law in 2013 has emphasized flood management as a policy priority.

In Wallonia, the emphasis has been on the protection of water catchments and the development of river tourism, with the regional laws on surface water (1985) and groundwater (1990). The regional government took a leading role, while the municipalities maintained an important function for ensuring water supply and treatment, particularly via the intercommunales—publicly owned companies operating in various municipalities. The region favored the establishment of local river agreements (contrats de rivière), which bring together local authorities, riparian users and local stakeholders to define a program of actions for the restoration of the rivers, their surroundings and the water resources of the basin. In 1999, an ambitious construction program and a new model of financing were designed to meet wastewater treatment standards after years of poor implementation, and a new regional company destined to water services provision and the protection of water catchment was created (Société Publique de gestion de l’eau). Integrated water management became a legal requirement contained in the Water Code (2004). In comparison with its Flemish counterparts, Wallonia has adopted a more decentralized and local style for water governance.

For its part, the situation in the Brussels-Capital Region is similar to that of any urban area worldwide. Apart from ensuring water supply via catchments in Wallonia, the main challenge for the Region has been to finance and build two enormous wastewater treatment plants to the south and the north of the city, inaugurated respectively in 2000 and 2007. The Brussels-South plant is managed by Vivaqua, a publicly owned regional water company responsible for drinking water catchment and distribution, and collection and treatment of wastewater in the region.[14] The larger Brussels-North plant, designed to deal with up to three quarters of the wastewater generated in the Brussels Region, resulted from a public-private partnership initiative and is currently operated by Aquiris, a branch of the transnational company Veolia. The second major challenge has been the renewal of the sewage network, which has been financed by important increases in household bills.[15]

To meet the WFD’s requirements regarding integrated water management, the three regional governments divided their territories into river basins districts (tributaries): 11 in Flanders, 15 in Wallonia and 2 in Brussels. The regional governments act as the main authority for the river basin districts flowing entirely within their territories, and also participate as members in the international river basins authorities for the Scheldt (the International Scheldt Commission – ISC) and for the Meuse (the International Meuse Commission – IMC) along with the governments of France and the Netherlands.[16]

Evaluation and future prospects

The development of water policy in Belgium has happened under the simultaneous and seemingly contradictory forces of Europeanization and regionalization. With the adoption of EU water legislation, the regional governments have put water management in their respective political agendas, have assessed water status in their regions, and have developed management plans to deal with water pollution and other difficulties along with riparian users and stakeholders. Water management and pollution have become a large-scale public problem deserving attention and resources. Important improvements have been made as a result. While in 2000 only 42 percent of the population was connected to at least secondary urban waste water treatment, in 2013 the percentage was 84.2 percent.[17] In addition, the ecological and chemical status of almost all water bodies in the country has improved in the last 15 years, and improvements are expected in all Belgian river districts by 2027.[18] However, there are still very important deficits, with over one third of all surface waters having a poor or bad ecological status and over half of groundwater reserves having poor chemical status.[19] Also, these improvements have had a price: water bills have increased considerably in all regions order to cover the costs of providing waste water treatment and renewing water infrastructures.[20]

Regional authorities have taken necessary steps to deal with many challenges in the sector—although there is still a long way to meet all the requirements of the legislation in force. More troubling is that water policy in Belgium remains vastly uncoordinated and divergent in the three regions. A firmer coordinated effort will be needed in the future as the three regions face population growth and climate change. Belgium is already close to hydric stress because of its high population density, but forecasts indicate that, by 2025, the country will have about 340,000 additional inhabitants—110,000 of them in water-dependent Brussels. In case of persistent and repeated dry periods, the demands on Wallonia’s reserves will likely put drinking water availability under threat. Also, the three regions are vulnerable against sea level rise. Although Flanders is the only region with a coastal line, increasing salinity of groundwater may cause more demands for drinking water in Wallonia, while slower flow at the mouth of the rivers may increase floods upstream. These circumstances require a common national policy for water resources management, which has not been developed. Indeed, the three regions continue to operate rather autonomously, and neither the coordinating committee CCPIE nor the River basin authorities have served to develop a fully-fledged national approach to water resources management and pollution. As global changes put Belgium under increased pressures, the country’s ability to assure a common policy for these challenges remains very much under question.

Monica Garcia Quesada PhD (LSE) is a researcher based in Brussels (Belgium). She has worked as Senior Researcher at the Institut de sciences politiques Louvain-Europe, at the Catholic University of Louvain (UCL) and at the Building, Architecture and Town Planning Department at the Free University of Brussels (ULB). Her work has been published in the Journal of Public Policy, the International Review of Administrative Sciences and the Journal of Public Administration, amongst others.

David Aubin holds a PhD in political science from UCLouvain (2005). He is professor at UCLouvain where he teaches policy analysis, evaluation and environmental policy. As part of Belgian and European comparative research projects, he studies policy work, environmental policies, and regulation of network industries. He was invited at Université de Montréal, KU Leuven and University of Colorado Denver, published in journals such as Policy Sciences, and Journal of Public Policy, and co-edited the book Policy Analysis in Belgium (Policy Press, 2017).

References:

[1] Tabari, Hossein; Taye, Meron Teferi and Patrick Willems (2015) Water availability change in central Belgium for the late 21st century, Global and Planetary Change, 131: 115–123.

[2] Authors’ calculation with data from Eurostat’s Water statistics, at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Water_statistics.

[3] Eurostat Water statistics, available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Water_statistics.

[4] Aubin, D. and F. Varone (2004). “The evolution of the water regimes in Belgium” in I. Kissling-Naef and S. Kuks, The evolution of national water regimes in Europe: Transitions in water rights and water policies, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 143-185. Aubin, D. and F. Varone (2001). “La gestion de l’eau en Belgique. Analyse historique des régimes institutionnels”, Courrier hebdomadaire, n°1731-1732 (2001), Bruxelles: CRISP, 75 p.

[5] Such as the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter and the Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment and Coastal Region of the Mediterranean Sea.

[6] Such as the framework laws for the protection of surface waters (loi du 26 mars 1971 sur la protection des eaux de surface contre la pollution) and for the protection of groundwater (loi du 26 mars 1971 sur la protection des eaux de souterraines). In addition, during this period, the first programme for research and innovation in the environment was launched. It was devoted to water projects and, in particular, the study of seawater, rivers and groundwater quality and management.

[7] Aubin, D. and F. Varone (2004). “The evolution of European water policy” in I. Kissling-Naef and S. Kuks, op.cit. 49-86.

[8] Garcia Quesada, Monica (2010) Water and Sanitation Services in Europe: Do Legal Frameworks provide for “Good Governance”?, UNESCO Centre for Water Law, policy and Science, University of Dundee: 60-82.

[9] Not without certain problems: the Commission took Belgium to the European Court of Justice (Case C-366/11) for failing to adopt and report its River Basins Management Plans to the European Commission in time. The ruling of the Court of Justice was published on 24 May 2012, whereby it was established that Belgium has failed to comply with its obligations as required by the WFD Articles 13(2),(3) and (6), Article 14(1c) and Article 15(1). The case was closed after Belgium adopted and reported all remaining plans.

[10] To some exceptions as the standards on products and ionizing radiations which remained federal. The competence on river and dam management was transferred to the regions later on, in 1988. See Aubin and Varone (2004), op. cit.

[11] Even if Belgium has been declared a federal state only in 1993.

[12] Accord de coopération du 5 avril 1995 entre l’Etat fédéral, la Région flamande, la Région wallonne et la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale relatif à la politique internationale de l’environnement.

[13] Mees, H., C. Suykens and A. Crabbé (2017), “Evaluating conditions for integrated water resource management at sub-basin scale. A comparison of the Flemish sub-basin boards and Walloon river contracts”, Environmental Policy and Governance 27, 59-73.

[14] Aubin, D., P. Cornut and F. Varone (2007), “Access to water resources in Belgium: strategies of public and private suppliers”, Water Policy 9(6), 615-630.

[15] Between 2005 and 2014, the water bill of a Brussels household of 2 people has seen a rise of nearly 60% (at current prices, based on average consumption of Brussels over the last 10 years). Bruxelles Environnement (2015) Consommation et prix de l’eau de distribution, IBGE, Collection de fiches documentees. Thematique Eau: 10. Available at http://document.environnement.brussels/opac_css/elecfile/Eau_6.PDF.

[16] by the treaties of Ghent (03.12.02).

[17]See Eurostat data at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Water_statistics.

[18] European Commission (2015) Commission Staff Working Document, Report on the implementation of the Water Framework Directive River Basin Management Plans. Member State: Belgium. SWD(2015) 52 final: 36-42.

[19] European Commission (2015) op.cit: 34-35.

[20] See, for instance, evolution of the water bill in region Brabant Wallon at https://www.inbw.be/prix-de-leau-et-evolution

Photo: Dried-up lake in Bourgoyen-Ossemeersen, a beautiful nature reserve in Ghent, Belgium | Shutterstock

Published on December 11, 2018.