This is part of our special feature on Water in Europe and the World.

An NGO Perspective.

Civilization was founded on the presence of water. The two cradles of civilization—the Nile Valley and the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers—were established around fertile river valleys that brought both the rewards of rich soils for agriculture, and perversely, the risks associated with the nutrient-laden flood waters. Whether we look in the Middle East, Latin America (both the Aztec and Inca engaged in extensive hydrological engineering), Asia (Angkor Wat is a giant labyrinth of water works), or Europe, water has always been at the heart of great civilizations and linked to their risk and fall.

One of the many waterways in Angkor Wat, Cambodia © Alexis Morgan

It is for these reasons that we should all take heed when we begin to experience the leading edge of climate effects. Climate change may be more aptly referred to as climate destabilization. And with a destabilized climate, extreme weather events—most of which manifest with either too much or too little water—become more the norm than the exception. The record drought of summer 2018 in Europe that affected waterways in the Rhine[i] was followed by flash flooding in Spain as post-tropical Hurricane Leslie struck the shores of the continent in the fall of 2018.[ii] Such water risks do not only manifest in terms of scarcity and overabundance however. From the water quality issues (in which the ecological status is rated as moderate, poor, or bad[iii]) that affect some 60 of European rivers, to issues of weak governance, water risk is a multi-faceted issue, and one that companies are increasingly recognizing.

Corporate water risk?

When it comes to corporate risk issues, water is often not top of mind for many companies. Yet, as climate change awareness grows, and companies and their shareholders increasingly begin to learn the financial perils of ignoring flood and drought warnings, or the massive potential fines from water pollution violations, we are seeing a growing level of awareness that water risks are indeed material to companies and their shareholders.[iv] Both reported environmental data, which suggests freshwater trends continue to grow more dire, as well as financial impacts reported both by companies and the insurance sector appear to indicate that water risks are growing more prevalent and more financially material.

It is therefore to be expected that data from the CDP Water Security program suggests that water risk awareness and reporting is gradually increasing.[v] While the quality of the reported data remains variable, and sophistication of the so-called ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) ratings used to interpret water risk and response is still lagging, at least the trends are headed in the right direction. Further evidence from CDP suggests that the trend that began with leading companies has now extended to the early majority of Global 2000 companies and to penetrate supply chains as well. Similarly, evidence from the World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report over the past decade suggests that water and other water-related issues (e.g., extreme weather events), remains quite top-of-mind with many global economic leaders.[vi]

Why is WWF engaged on corporate water risk?

Freshwater was not only the basis for human civilization—it was, and remains, the basis for all life on Earth. Environments endowed with significant freshwater—from wetlands to tropical rainforests—are amongst the most biodiverse on the planet. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that WWF, the global conservation organization, is engaged on freshwater around the world.

What may come as more of a surprise is that the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is an active player helping companies tackle water risks. Since 2011, WWF has been working at the forefront of water risk helping not only corporate partners, but also the financial sector to navigate water risk issues. But why is WWF helping businesses?

The logic for our engagement is simple: freshwater biodiversity has declined some 83 percent since 1970,[vii] suggesting we need to undo significant damage. To affect change at scale, you need to engage those who are capable of mobilizing capital and resources large enough to change the status quo. In other words, to save freshwater species and habitats, you are going to need companies and often, their agricultural supply chains. On a global average basis, 70 percent of water withdrawals (90 percent of consumption) come from agricultural water use and thus companies with food and fiber in their supply chains are key to affecting change.[viii]

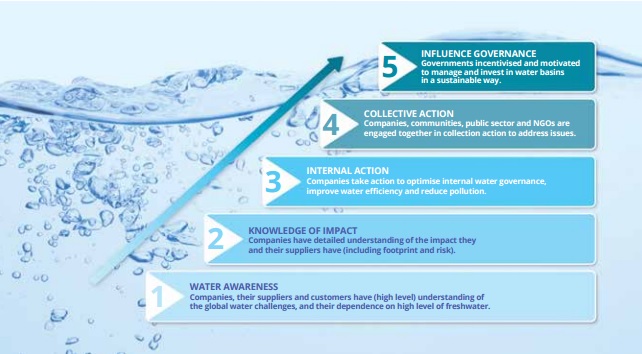

While WWF has long worked on freshwater issues, from 2006 to 2008 there was a general emergence of a new paradigm in response to what some perceive as the failure of government-led river basins management to stem the growth in basin water risks: water stewardship. Water stewardship is defined as “the use of water that is socially equitable, environmentally sustainable and economically beneficial, achieved through a stakeholder-inclusive process that involves site and catchment-based actions.” (AWS[ix]). WWF’s working theory of change (Figure 1) was that through moving companies up a progress of internal actions and collective action, we could ultimately create a critical mass of companies that could in turn be harnessed as powerful advocates for progressive, good water governance.

Figure 1: WWF’s water stewardship ladder

Source: WWF[x]

However, to mobilize companies on their water stewardship journeys, WWF and other conservation organizations turned to the narrative of water risk, and later, explored how water risk can affect value. These concepts were familiar territory to many corporate staff, who have long engaged in enterprise risk management.

Framing corporate water risk

Stemming out of shared thinking on corporate water risk exposure developed around 2008, WWF and others involved in guiding the private sector on this topic, classify water risks into three broad categories: physical, regulatory and reputational water risk. These three forms of risk come together and manifest ultimately as financial impacts (sometimes referred to as financial risks).

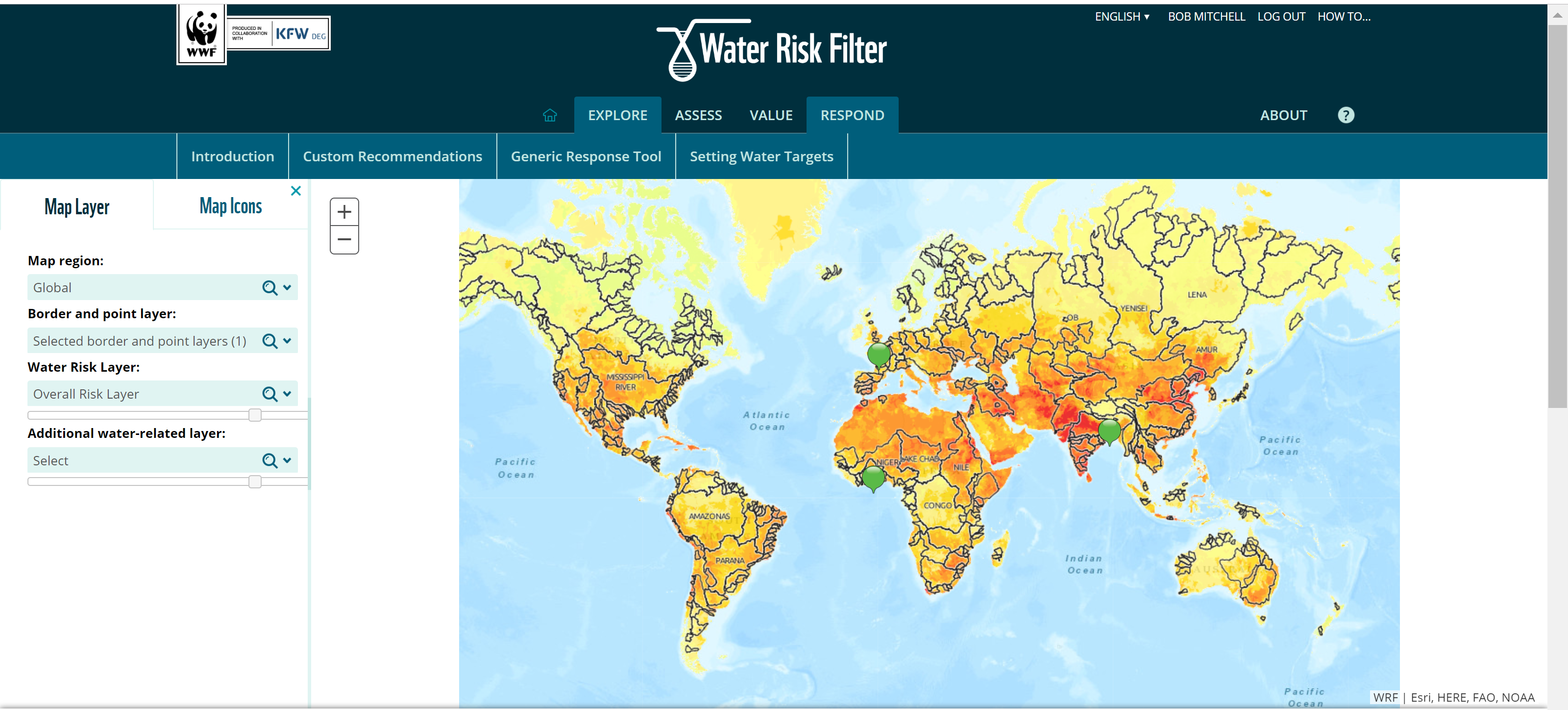

It is this broad classification that forms the basis for our global, online, freely available water risk assessment tool: the Water Risk Filter (WRF).[xi] The WRF has been online since 2012 and has been used by more than 3000 unique users to assess over 250,000 sites across all continents.

From Water Risk to Response

In the fall of 2018, building on lessons learned, WWF rolled out the latest modification to the WRF. Indeed, the past decade of corporate water partnerships, from Coca-Cola to H&M, have taught us a significant amount about not only good practice, but challenges and opportunities as well. It was with this in mind that we updated the tool, in an effort to return to the primary aim: mobilize corporate activity at scale to affect system level change that can stop and then reverse the loss of freshwater biodiversity.

So what have we learned and where are things going next?

1. It is important to assess water risk, and perhaps even more important to assess water opportunities.

Over the past six years, we have seen dozens of Global 500 companies use the Water Risk Filter to assess their water risk. While this is a useful beginning, the risk narrative is fundamentally rooted in stopping the bad, rather than promoting the good. As any investor knows, where there is risk, there is often also reward. Accordingly, in the new version of the Water Risk Filter, we’ve started to think about how we can leverage the data to find opportunity as well. By drawing on site water risk data, and corporate partnerships, we’ve begun to roll out a new initiative called “Bankable Water Solutions.”[xii] This initiative marries commercial lending, profitable investments, and tackling water risk, by bundling projects to achieve scale. The “business case” for water and for water stewardship continues to grow stronger and stronger.As we move forward, increasingly more of our work is about finding opportunities. Opportunities to save costs, to retain purpose-driven talent, to invest in cost-effective green infrastructure. Water has a huge number of untapped, profitable investments, and so we have started to add “opportunity matchmaker” to “risk advisor.” Learnings in behavioural psychology suggest that such shifts in narratives are critical as we seek to motivate the mainstream to join.

2. Water has multiple values to multiple audiences, but finance people talk money.

In 2015, WWF and IFC jointly published a framework document that sought to link water risk, water stewardship and water valuation.[xiii] This report not only explored the multiple forms of value that water can take – from financial to spiritual, but also presented a case for how water risk events could affect different aspects of financial statements. By 2018, the CDP Water Security programme had gathered more than four years’ worth of reported data on the links between various water risk events and how those affected financial value. Not only does this enable insights into which kinds of water risks are most commonly reported (answer: water scarcity), but also how water scarcity most often affects income statements (answer: higher operating costs). The more than 10,000 data points give a reasonable sample to infer how water risk and financial value most commonly link.

Building off of these insights, the Water Risk Filter has incorporated two new tools: a valuation approach finder and a value potentially affected calculator. The former was developed out of a recognition that many people were confusing different approaches when it came to finding resources to help them find “the value of water.” Some were seeking methods to calculate water tariffs (i.e., water pricing) for water service providers, while others were interested in calculating the value of freshwater ecosystem services.

The latter, the value potentially affected calculator is powered by the CDP water security data, and takes advantage of user input, a Monte Carlo simulation, to offer users insights on how water can not only affect different elements of an income statement, but in turn be built into a discounted cash flow analysis to help inform investment decisions. The hope is that through this new tool, we can better equip internal staff to help mobilize more resources and drive positive change at greater scale.

3. While leaders might know what to do next, many need to be guided from risk to response

Our time working on water stewardship taught us one lesson in particular: even with an explicit understanding of water risks in hand, companies can still manage to implement solutions that do not match the problem. We continue to find that many companies believe that shared water scarcity challenges can be solved through improved efficiency measures. The evidence, linked to the concept referred to as the Jevons Paradox, suggests otherwise. No one questions that water use efficiency can create savings. But equally, too few people question what happens to those “water savings.” Most often, rivers, wetlands and other freshwater systems do not see such savings and instead they go to greater production.[xiv]Where that reality led us, was to begin to explicitly match solution with problem. The new version of the Water Risk Filter uses the basin and operational risks unique to a given site, to prioritize different, contextually relevant, response actions (Figure 2). Furthermore, we’re now starting to develop new, science-based target methods that will allow us to better model cumulative sustainable water use and explore shared targets. We believe that this may help user in the shift from risk to meaningful response.

Figure 2: The updated Water Risk Filter

4. There is strength in numbers

The numbers regarding freshwater biodiversity, as mentioned at the outset of this paper, are not only disheartening, they represent a shared failure. Water is not simply life giving, it is a right. A human right, and a right for other species that share our planet. Water is also not just a shared right, it is a shared responsibility. And it is a responsibility that we are failing to live up to.While sectoral collaboration has progressed, collective action at the basin level at the scale necessary to tackle the challenges at hand, have largely not. We have far too few examples of effective collective action & collaboration.

Nevertheless, those working to change this narrative have not been idle. Over the past decade, we have collectively worked to lay the foundation for collaboration at scale. The development of the Alliance for Water Stewardship (AWS) standard helped to not only create the definition noted earlier, but brought together an accepted shared framework and a common language. Furthermore, the process of developing a joint standard developed relationships and trust. These elements, collectively, are critical precursors for collaboration at scale. AWS continues to grow, and as it does, the number of potential allies to implement scaled basin collaboration also grows.

The trends on water stewardship are ultimately both promising and concerning, simultaneously. We’ve lost most of our wetlands and most of our freshwater biodiversity. Conversely, we’ve got more, and more powerful, allies than ever before and a common language, with powerful tools, with which we can begin to mobilize at scale. What we now need is the willpower to organize and take action.

Water stewardship represents a new approach, borne out of both need and recognition that our failing river basins will not be “saved” by government. Rather, if we are to restore water ecosystems, and provide water security – for businesses, for communities and for the environment – we need to take collective responsibility for shared, common pool resources.

Alexis Morgan is the Global Water Stewardship Lead at WWF, where he has worked for over 15 years. He helped to develop the world’s first water stewardship standard with the Alliance for Water Stewardship (AWS) and has also led the development of leading water tools such as, WWF’s Water Risk Filter. Alexis regularly publishes on water risk, water stewardship, water valuation, sustainability standards, and freshwater conservation. He sits on CDP Water’s advisory board and currently serves as chair of the AWS’s board. He holds degrees in Geography, Hydrology, and a sustainability-focused MBA and lives in Vancouver, Canada.

References:

[i] AFP. “Water woes as drought leaves Germany’s Rhine shallow”. Phys.org. October 19, 2018. https://phys.org/news/2018-10-woes-drought-germany-rhine-shallow.html (accessed November 14, 2018).

[ii] Matthew Cappucci “Zombie storm Leslie slammed Portugal, France and Spain with unusual strength” Washington Post. October 16, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2018/10/16/zombie-storm-leslie-slammed-portugal-france-spain-with-unusual-strength/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.f47cfe876e15 (accessed November 14, 2018).

[iii] Peter Kristensen, Caroline Whalley, Fernanda Néry Nihat Zal, Trine Christiansen. European watersAssessment of status and pressures 2018. EEA Report No 7/2018, European Environment Agency, 2018.

https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/state-of-water

[iv] CDP. A turning tide: tracking corporate action on water security – CDP Global Water Report 2017. https://6fefcbb86e61af1b2fc4-c70d8ead6ced550b4d987d7c03fcdd1d.ssl.cf3.rackcdn.com/cms/reports/documents/000/002/824/original/CDP-Global-Water-Report-2017.pdf?1512469118 (accessed November 14, 2018).

[v] CDP. A turning tide: tracking corporate action on water security – CDP Global Water Report 2017. https://6fefcbb86e61af1b2fc4-c70d8ead6ced550b4d987d7c03fcdd1d.ssl.cf3.rackcdn.com/cms/reports/documents/000/002/824/original/CDP-Global-Water-Report-2017.pdf?1512469118 (accessed November 14, 2018).

[vi] World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2018, 13th Edition. ISBN: 978-1-944835-15-6. World Economic Forum. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GRR18_Report.pdf (accessed November 14, 2018).

[vii] WWF. Living Planet Report 2018. https://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/all_publications/living_planet_report_2018/ (accessed November 14, 2018).

[viii] United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. “Facts an Figures about [water]” http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/didyouknow/index2.stm (accessed November 14, 2018).

[ix] Alliance for Water Stewardship. “Leading the way in water stewardship” http://a4ws.org/about/impacts-of-aws/ (accessed November 14, 2018).

[x] WWF-UK. Water: a risky business. https://blogs.wwf.org.uk/blog/habitats/rivers-freshwater/water-risky-business/ (accessed November 14, 2018).

[xi] WWF. “The Water Risk Filter” http://waterriskfilter.org (accessed November 14, 2018).

[xii] WWF. “Bankable Water Solutions” http://wwf.panda.org/our_work/water/bankable_projects/ (accessed November 14, 2018).

[xiii] Alexis Morgan and Stuart Orr “The Value of Water: a framework for understanding water valuation, risk and stewardship.” https://commdev.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/The-Value-of-Water-Discussion-Draft-Final-August-2015.pdf (accessed November 14, 2018).

[xiv] Conor Linstead “The Contribution of Improvements in Irrigation Efficiency to Environmental Flows”. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 06 June 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00048 (accessed November 14, 2018).

Photo: Rocks underwater on riverbed with clear freshwater, Dumbea river, Grande Terre, New Caledonia | Shutterstock

Published on December 11, 2018.