Translated from the Danish by Jennifer Russell

DANIEL FOUND HER IN the ground.

He dug her free and brushed off the dirt. He joined the pieces, logged the pigment traces: how they were distributed across her clothes and her skin. Her blue-green eyes. Her coral lips. He carved new marble and filled the holes where fragments had been lost.

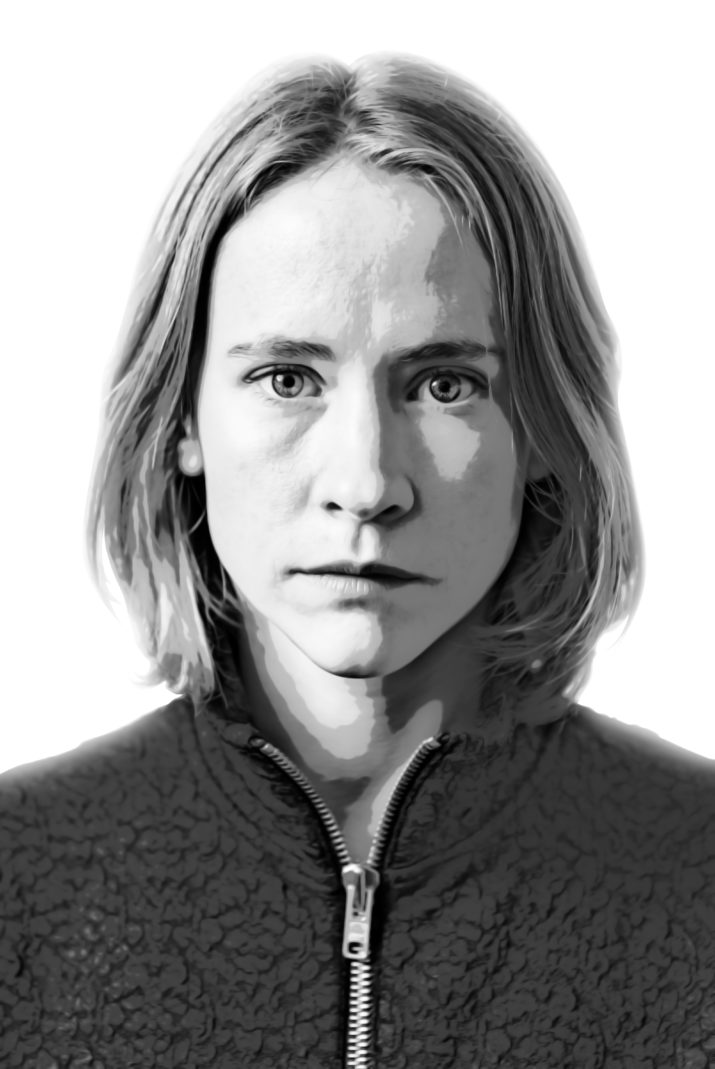

Her name is Marble. Daniel calls her Maggi.

“Maggi.”

Her body fills with blood that can flow in every direction.

Daniel places her on the bed. He asks what it feels like to be her. She says that her ears are small microphones. When he strokes her earlobe, it sounds like wind through a wind muffler. Now the blood flows to her legs.

Daniel lies down and Marble turns to face him. Her right hand grasps his left thigh, she pulls it across her hip. His left hand closes around her right breast.

She finds his mouth in a darkness that comes from her own closed eyes. A kiss so deep and honest, like slowly opening an abyss with your tongue. Massaging it forth.

Marble pulls back her tongue.

“Daniel, what do you see behind your closed eyes?” she asks.

“Orchids,” he says and looks more closely. “Orchids, spread throughout enormous greenhouses. And fluorescent tubes that twist through amber honey. A hand pressing small pieces of charcoal and coral into the sand on a long, white beach. And colors that seep into other colors, quickly and almost imperceptibly.”

“I see sculptures when I close my eyes,” says Marble. “Antique sculptures with brilliantly painted surfaces. Not just one color, but a multitude of saturated colors covering the form. Polychrome. A surplus of color.”

“The color isn’t superfluous,” says Daniel.

“It isn’t superficial, either,” says Marble.

Now the moon casts a window of light onto the floor. Marble gets out of bed and sits on the floor and looks at the moon window.

She lights a cigarette and blows white smoke out into the moonlight. The smoke doesn’t smell of anything. She passes the cigarette to Daniel in the bed. They take turns smoking.

Marble with the cigarette pinched against the loose skin between her fingers, the entire palm of her hand beneath her chin.

“Forms are eternal,” she says. “And materials are eternal. It’s when they meet that time begins.”

Daniel blows a smoke figure that looks like a horse’s head.

“You can carve a form in marble and let it travel through centuries,” he says. “It never stops occupying a space in the world.”

“Yes,” says Marble and blows at the horse head. “But the color slips off.”

Dear Laila,

if the surface is where an object ends, then nothing can be kept there. If you try to pinpoint it, it becomes thinner and thinner until it is nothing but an idea. The surface seems to border on the immaterial.

But at the same time, we encounter the world by virtue of its surfaces. We encounter the outermost layer of everything, never anything but that—through reflection, resonance, touch. Are we then only encountering ideas? Do we reach out and touch them all the time?

Daniel and I visited the cast collection today, in the warehouse down by the harbor. We wanted to take a closer look at the casted surfaces. When a form is reproduced in plaster, the air is solidified around the form. Then the copy is casted inside the cavity. The form is folded around its own immaterial surface.

The collection consists of three stories crammed with plaster copies of Western sculpture. We walked around among the copies as if they were something other than plaster in familiar forms. The Laocoön Group, Venus de Milo, etc. The form transcended the plaster like an echo that said: You’ve seen me before. I was deeply moved. I couldn’t help but touch the plaster. I thought: The plaster does not know what it represents, but potentially it can represent everything.

But Daniel pointed out something black within the folds of the sculptures and said: That’s time.

And: The muzzle of the Parthenon horse head shines because the plaster has drunk from the hands that have touched it.

The cast collection’s surfaces have a history. They have stood at the Academy of Fine Arts, where they gathered dust and were painted white instead of being cleaned, and later at the National Gallery. Again and again they were found worthy of being touched and reproduced and restored.

I said: But these sculptures were created white. There are no traces of paint.

Then we noticed the painted plaster of the Greek korai statues. And Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen’s colored reproductions from the Acropolis: the Typhon and the Bull’s Head.

So everything wasn’t white after all.

Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen!

Give my regards in New York,

MARBLE

DANIEL AND MARBLE BORROW a car and drive south to the limestone quarry outside the town of Faxe. At the quarry is a small museum where they see a black-and-white photograph of a house dusted white by the smoke from the lime kiln; white roof, white grass, white laundry on the clothesline.

They stand at the vantage point behind the museum and look out across the quarry. The sun is shining, and white reflects all the colors. The quarry’s lakes mirror an ice-blue sky.

It’s Sunday, and the excavators and conveyor belts that operate all week extracting the limestone, processing it, and sorting it into piles according to particle size now stand still.

Daniel and Marble descend into the quarry by foot. It’s quiet down there. They can hear the croaking of hundreds of frogs next to a whitewashed and ice-blue shore. And someone cutting into the limestone. Ding—ding—ding.

A middle-aged couple in sandals and caps comes into view behind a big pile of limestone; they carry tools and buckets. Marble and Daniel can hear fragments of the couple’s conversation even though they’re far away and speaking softly. They speak German to one another. Sound travels easily in a mineral landscape.

The couple sits down and carries on splitting the limestone.

Daniel walks over to them. Marble sits down by a lake and listens to the frogs’ mating calls. We’ve dug into another era, she thinks. She hears Daniel talking to the couple.

He returns with something wrapped in a German leaflet. Marble unwraps it. It’s a lump of limestone that has been split.

“Limestone?”

“Yes. Take a proper look.”

She holds it up and peers into a criss-cross of tiny white fossils, branch-shaped, sausage-shaped, tube-shaped, so fragile it’s hard to believe they weren’t crushed long ago.

“Faxe coral,” says Daniel. “There was a coral reef here sixty-three million years ago.”

“Here?”

“Yes, and it’s still here. What we’re walking around in is the fossilized skeletons of the coral reef.”

“Skeletons?” asks Marble. “Is coral an animal?”

“A coral reef consists of polyps that create a shared skeleton across generations,” says Daniel. “The Germans told me. They’re amateur geologists.”

Marble turns the lump of limestone over and tiny fossil fragments sprinkle out.

“If corals share a common skeleton produced across generations, can the entire coral reef be considered a single organism?” asks Marble.

“Why?”

“Because that would mean we’re standing in the middle of one gigantic skeleton,” she says.

Daniel laughs.

A chill runs down Marble’s spine. She doesn’t know whether it’s the many small skeletons or the single large one that makes her uncomfortable.

Just then a fighter jet flies over the quarry. At first it appears as an image, so close they can see its underside: the joints of the metal plates. A quick glimpse of a different scale; very big, very close, very fast. Then comes the sound: a long blast that lingers in the quarry long after the image of the jet has disappeared.

DANIEL WAKES UP AT NIGHT and watches Marble sleeping. Her face is relaxed. Only her eyes move beneath her eyelids.

A truly relaxed face is the face of the dead, Daniel thinks. In sleep too you present your face, tautly stretched like a kite in the wind of a dream.

Marble dreams of a diver kneeling on the ocean floor. He wears a shining copper helmet and a thick canvas suit. His breathing tube winds underneath his arm.

The helmet is attached to the suit with bolts that Marble unscrews. She lifts off the helmet. The diver’s face is shapeless like a lump of dough. It has no form.

Marble wakes up and looks at Daniel. He turns on the light. She smiles at him. He smiles back.

What do you do with reciprocated love?

“I’m going,” she says.

“Going where?” he asks.

“To Athens,” she says. “I want to take a closer look at the surfaces of antique sculptures.”

Amalie Smith (b. 1985) is a writer and visual artist based in Copenhagen. She graduated from the Danish Academy of Creative Writing (Forfatterskolen) in 2009 and the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 2015. She made her literary debut in 2010 and has since published seven hybrid books. Her visual work has been shown at major art institutions in Denmark including Kunsthal Charlottenborg, ARoS, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Roskilde and the National Gallery of Denmark, and internationally in Melbourne, London, Leeds, Reykjavik, Riga and Ulaanbaatar. Smith has received several prestigious grants and awards, including the Danish Art Foundation’s prestigious three-year working grant and the Danish Crown Prince Couple’s Rising Star Award.

Jennifer Russell is an editor and literary translator from the Danish based in Copenhagen. She holds a BA in art history and English from the University of St Andrews and an MA in Critical Studies from the Pacific Northwest College of Art.

Copyright © 2014 Amalie Smith & Gladiator

Translation copyright © 2018 Jennifer Navntoft Russell

Published on December 11, 2018.