Translated from the Spanish by Layla Benitez-James.

This is part of our special feature on Crime and Punishment.

Introduction

I am one of those people who has always recognized that one comes to Europe, that is, to the land of the whites, in search of what I have referred to as “the other knowledge.” A knowledge that I needed to add to the “little” that I already brought from my village and, therefore, create a mixed world within myself. More than forty years later, I believe I’ve arrived at the moment to reflect, be it only in a basic and elemental way, on my view of the world from this continent, considered one of the “paradises” of our small planet, and find some kind of balance between what I have seen and learned. And, even though one never learns or sees enough, I think that today I can begin to tell the very little that I have been able to perceive and learn….

I

Vision of Europe from Africa

Previously, in my book Spain and Black Africans to be exact, I tried to explain the understanding many Africans, myself included, had of Europe from our continent before we set foot on these lands: “Europe is understood as a species of promise land; a place free from all sin, from misery, a place without the injustice of men or gods…A place that awards ease and opportunities in every moment and to all. It´s possible that, at some point in history, some people from Africa will even begin to relate their unknown Europe with the Paradise preached by the Bible.” [1]

I was part of those Africans who had that understanding and that view of Europe. Although I no longer hold that idea of Europe as an Eden, four decades after my first stay on the continent, this thought continues to be at home, even today, with many Africans. In fact, as I was immersed in the idea of continuing with this writing, an older black African woman confessed to me one day in Barcelona: “Before coming here, to the land of the whites, I believed that they were like God, that they did not die.” She said it with great admiration, despite knowing by this time that whites also die. I had just been gazing, in awe, at the colored lights that flooded the city during the Christmas season. And it is precisely because of all this, and the long time that I have spent among whites, learning and, above all, observing, that I have concluded that our black Africa must change! Yes, black Africa must change, and it must vary its course however it can! Up to this point, the obsession of almost all Africans has been to make our black Africa look like Europe, and we Africans to act like Europeans. This attempt constitutes a grave error. It is true that every human being should always imitate and copy what´s better and what´s best, but the white man, our theoretical model, is not exactly a paragon of virtues, neither are they all his own. Therefore, we must do everything possible to cure this obsessive neurosis! If we look closely at the great failures that our continent is suffering after the alleged independence obtained from the colonizers, we can understand that all of them are due to the fact that the motherland´s “own spirit” refuses to follow that path and that example strictly.

Africa, our old and beloved continent, is an ancestral land, just like her inhabitants. Africa is the beginning of everything. As is said and known, the life of all humanity and its history began there. Domination by other peoples should not make us forget this reality. The black peoples of Africa were defeated and dominated but, despite these multiple defeats, we cannot and should not forget that we are still an old and great people. Why not think, then, that many of our great current failures are due to the fact that the spirit of our elderly mother, Africa, does not want us to triumph on the path that all our nations have struck out on. The path: to strictly follow the mandate of the Europeans, to be and act like them.

If many of us make an effort and try to reflect on the experiences we have accumulated throughout our lives, we can conclude that black Africa must change. The course must be varied. Throughout the history of mankind, the dominance of a human group forming an empire or several at the same time has been constant. Then, this or that empire has ended up collapsing, having lasted centuries or not. This collapse should be thought of with sadness even by those who have not been part of it. But it’s not so. And it´s not so because each empire has always meant enormous suffering and constant agony for those humans who were not part of it, but who suffered the consequences of their negative aspects, their evil. No empire, be it of race or of continent, has been benevolent to the people it dominated. The latter have always been dragged. Nothing they were or represented could be considered important. They were part of the “inferior species,” so they were treated as such, without any regard. The doctrine and customs of the rulers were and still are the most valid. Despite dominating, they did not cease in trying to inculcate their culture, their way of being, trying by all means to neutralize or destroy those other customs.

However, it is not only the great empires who have exercised their repression on the defeated of their particular time and place. Some ethnic groups, tribes, even countries, have acted in the same way when they have had occasion to do so. When they have accumulated more power than others. Animal instinct and ferocity are ruthless towards the weakest.

Meanwhile, the oppressed, who has suffered all kinds of humiliations, ends up accepting his condition of being inferior. His only struggle in life becomes none other than to copy his oppressors´ way of being and doing. This way of life is steeped in guilt and inferiority complexes. Nothing of what his people did before the dominator´s oppression has any value, although he may evoke it from time to time in his mind. His goal is to become like his oppressor. Many times, he may even try to outdo his model, both in the good and the bad, although the predominate element leans to the worst, the most evil of the other. The oppressed person´s great values become insignificant customs. Nothing of what they do in their town is important if you do not authorize it by being the oppressor and most powerful in the moment.

The oppressed person´s struggle, one with an inferiority complex, becomes a baseless battle to attain the goals or objectives of those considered superior victors. They will never stop to try to reflect and meditate if they are on the right path or not. They are completely blind, only wanting to be or to do in the image and likeness of the powerful.

This is more or less the struggle we developed, we black Africans. We fight with all our might to resemble our goal of Western European countries that have dominated and oppressed us for centuries. The aim is to be and act like Europe. Our old values no longer make any sense, because they do not resemble those of Europeans. That’s why we run, blind and harried, dodging any obstacle, to incorporate ourselves into the materialistic, scientific civilization of the white man.

But it is possible that black Africans are wrong, that we have not chosen the right path … It is possible that the spirit of our old mother Africa does not expect this from her children. We must pause a little from time to time, reflect on this crazy race that we are running. If we continue like this, we run the risk of slamming ourselves against a wall and remaining dumbfounded for a long time, without knowing again who we are, as we have throughout the era of slave oppression and colonialism.

III

Spain (first moments)

Spain, in the seventies, was a country immersed in full on dictatorship. However, in those times, a black African youth like myself was far from distinguishing, let alone knowing, what a real dictatorship meant. But even if I had known it, I doubt that I would have cared. One of the things that I appreciated in those moments was my personal inner balance to keep from collapse, and I think I found it. I grew up between towns of great black African traditions, what we can call deep black Africa. A lucky thing that, later in European lands, always helped me to maintain balance. It´s what I described later as “the wall of contention” that every individual needs when faced with adverse situations such as those that we, as many African immigrants have in Europe, have been forced to face.

I came to understand how important the first years of an individual’s life are. His childhood, his adolescence and something of his youth. The teachings and experiences of these stages are complete. At least they have been for me. In these three stages a strong wall of contention was created, they have made me love and, above all, understand, our old mother, black Africa. From a distance I have always carried it in my heart. That is why I feel the strength and the moral right to ask and affirm today that our black Africa must change. One needs to vary the course.

Spain was, then, a country of humble people. Humble both in their manner and in their social conditions in life. It took no effort to adapt to their environment. But, in spite of that, one was black and foreign, coming from a poor nation. In those times there was not a considerable black population. The few who resided here were all students and the majority of Equatorial Guinean and Latin American origin. Many African-Americans who served on the military bases that the United States had on Spanish territory were also seen in Madrid.

This shortage of blacks in the whole Spanish territory, at that time, sometimes caused certain misunderstandings among the Spanish. They were used to hearing in their media and in their churches that blacks were poor people, people to whom Domund’s Mission donations and other works of charity were destined. But the “blacks” that were arriving did not quite fulfil this role. This, logically, caused confusion. On the other hand, it was normal. All the black students of that time, both African and Latin American, were scholars or were being supported, as was my case, by parents from their respective countries.

Precisely because of those misunderstandings, my doubts about the “perfection” of the way of life that I had on this earthly “paradise” where I had landed began to grow. So, for example, after finishing my last year of high school, I enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine. There was no end to my surprise when, days later, the secretary let me know that I had to travel to Madrid to validate my degree. I wanted to argue, to tell her that, as I could well prove, all my high school diplomas were Spanish.

“Don´t argue, hurry to Madrid to avoid missing the course!” the woman told me with all her good faith and kindness.

Once in Madrid, I went to the Ministry of Education. There, the lady, or young lady, who attended me scolded me for not coming to validate my degree earlier, in March.

Desperate, with tears in my eyes, I explained again that I could not have done so in March, I was still studying at my school in Valencia, and that the course did not end until June. She shrugged her shoulders and told me the same again, and that I must wait until March of the following year.

Luckily, the woman, perhaps seeing my state of despair when I was leaving, followed by my friend, suggested that I try to go to the Coordination Office. When we arrived at that place, my partner and I found an older man. After explaining the reason for my visit, the man flew into a rage and spent about two minutes releasing all kinds of curses and profanities … and then, at last, apologized. He explained that his anger stemmed from nothing more than being sent more and more of these senseless cases.

“Why didn´t you ask them what they wanted you to have your degree translated into, into Chinese perhaps?” He then sat down and wrote a letter stating that for every student who has studied in Spain and in Spanish, be they of whatever race or nationality, that their degree had the same validity in Spain as that of any Spanish student. That’s how I was admitted to university.

As the official told me, my case was not the only one. In fact, I later learned that an Equatorial Guinean student was also rejected because he did not validate his architect’s degree, despite having studied architecture at a university in Madrid, that is, in the same city where his title was rejected…

That type of confusion was very frequent in the Spain of that time. Those misunderstandings could both ruin your life or make you very happy; everything depended on the circumstances. To me, personally, they embittered me many times, but they also occasionally worked in my favor, so it was fun for me. I had gotten used to it. So, for example, for many years I was able to renew my residence permit, thanks to these, “confusions.” Sometimes I went to the Social Security Office to renew my papers. The duty officer asked me for things I did not have: a certificate that attested to having a large amount of money in the bank, or anything else. But when I realized that I lacked whatever requirements, I´d return quietly to my house and wait. After a few days, I´d go by again and find the same official, but this time he´d ask me for different things, such as two electricity or water bills, something that would give an account of my home in the city. Then I would go home to look for them and solve the problem immediately. That’s how I existed for many years; those “confusions” amused you in the same way that they annoyed you. That is, they could help you or they could complicate your life … One day I met a French citizen in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Madrid. The man, with a pained expression, approached me and said: “Excuse me, sir. Do you know what the Spanish really want?” I did not know, of course, but I suppose the Spanish didn’t either.

However, my encounter with that Frenchman in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs marked me a lot. Until then I had not reflected on the possible defects that the owners of “Paradise” could have, if they should harbor any defect at all. I was born in the bosom of a Protestant Presbyterian family, and like almost all the inhabitants of my town, went compulsorily to church every Sunday. From a very young age I had always heard how the pastor or preacher on duty enthusiastically recounted the punishments that God inflicts on us, the mysteries inhabitants of the world. The plagues of Egypt, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah and other punishments no less severe. From where I sat, I had seen how the preacher pointed me out, and all of us who went to that religious place, accusing us of being the culprits, those responsible for the horrendous crimes narrated by the Bible. At that time, I dared not question the authorship of God himself in all that happened, much less think that in all those barbarities related by the Bible, God, the owner of paradise, could have had some participation or guilt.

That’s how I was until I met that Frenchman. It was he and his question that made me “guilty” and caused me to begin to question many things of that “paradise” where I was already situated. He was white like the Spanish. Therefore, like them, he was also an inhabitant and owner of the earthly “paradise” where I was already living on loan, and to which many inhabitants of my continent would like to come to live comfortably. But that this Frenchman should question, in front of a black man like me, the perfection of his white Spanish brethren, gave me much to think about. With the passage of time, I connected my astonishment and my doubts with those which black Africans must have felt when they were called by their colonist masters to fight in the Second World War. That is, called to help them kill other whites like themselves. As for those relatives, near and far, nothing was the same after suffering the experience of war; I also felt something similar after that Gaul´s question. Already, nothing was the same for me and my blind admiration towards the inhabitants of the earthly paradise, where I had emigrated.

IV.

Confusion in Eden

Logically, with the passage of time, my confusion was growing larger and larger. As the dictatorship in Equatorial Guinea strengthened, the situation of that country´s students became increasingly difficult in Spain. And, like them, my situation became unbearable, because they did not let any money come out of the old colony.

I took advantage of some of my relatives having residence in the north of France to cross the border to work there during school holidays. I was soon struck by the fact that, no matter the country, every time I crossed the border, the police displayed a derogatory and arrogant attitude towards immigrants who, like me, came from the Third World. Our passports were thoroughly checked by the officers with disgust on their faces, who then addressed us with questions formulated with aggression and harshness. Everything would have seemed normal if the contempt of those guards was also directed at the Spanish and Portuguese citizens, with whom we agreed on the borders of Europe. I also observed that, because I was black, and my passport was that of a poor country, my presence and my papers inspired a feeling of nausea in the expressions of the officers; however, that attitude changed completely when the black man who followed behind or went in front of me, presented a US passport.

At that time (seventies and eighties), the United States had deployed numerous military bases in various European countries. When an African-American citizen showed up, his passport was reviewed with respect. As if by magic, expressions of contempt disappeared from the officer´s faces. Moreover, if the officer in question did dare to delay the passport´s return, its owner would get angry and shout, and the officer would rush to return his document, requesting all kinds of pardon.

In the face of such attitudes, my confusion was increasing. I was discovering that, in Eden, the people who inhabited it received different treatment. Here and there, skin color did not influence as much as one might think; it was, in fact, based more on the individual in question´s documents which certified that he came from a poor or rich country. The situation then changed. I began to realize that what is decisive in our world is not so much the thorny issue of race—black, white, yellow, coppery or olive, still very much mattered, of course—but the fact of being rich or poor, weak or powerful at the right time and place. I could not tell if that discovery made me happy or sad. The only thing I recognize is that, both then and today, I am still invaded by a terrible sense of confusion whose depth is unfathomable.

In the seventies, the United States was immersed in a long struggle for the civil rights of its black citizens. They did not mean anything in the eyes of their fellow white citizens, but abroad, that country was feared and respected for how powerful it was, so much so that their blacks also became powerful citizens.

At that time, Spain was very poor, and exported its poor to richer countries so that these citizens received from their brothers of similar races and shared continent a generally degrading treatment. A situation that black Africans did not yet experience so severely because black Africa still did not massively export its poor to the rich countries of Europe.

The poverty of Spain and the power of its brothers and neighbors created an exaggerated obsession among Spaniards. The obsession was none other than to look like Europeans, in fact to be Europeans, because, in that time, the Spanish did not seem to be European, but instead as if they were citizens of the third category compared to the rest of their more developed continent.

I understand that human societies should do everything possible to import certain characteristics of their brothers or neighbors, whether they are of the same race or not. But, before copying, it is important to decide if what they are going to adopt is really compatible with their way of being and acting. Or if everything they want to copy is better than what they want to leave. Those in powerful, the oppressor of the moment, never discovers defects in his way of being. As I mentioned before, sometimes, even one´s worst defects are considered great virtues by others and, of course, by one´s subjects. It is curious the blindness that overcomes a person low down the rung of power.

I remember a trip in which I was accompanying a couple from France in a car. He was black; she was white and French. We left Valencia, where I lived, and drove to Alicante. I was in the backseat and the couple was in front. The black man drove. On the curve of an exit, the Guardia Civil stopped us. By taking the curve, the driver had clearly crossed the continuous white line, and so the guard informed us. While the two officers were asking for our documentation, the Frenchwoman bounced out of her co-pilot seat and began to shout all kinds of curses. “L’Espagne la merde, the dictature, la France est la démocratie …” (Spain is shit, the dictatorship, France is the democracy …). She screamed this again and again, among other things. The two officers looked at each other and, immediately, returned the documents from their car. I went back into the car with my head down, self-consciously and with a vivid feeling of embarrassment. We had clearly committed a violation and I could not understand how the guilty party could become aggressive and transfer the blame to those who had pointed out the fault. As we started the car again, I heard one of the officers say, as if to justify themselves: “A violation is a violation …” We started off, and the French woman continued to ridicule the Spaniards for their dictatorship. That scene reminded me of many others that I had seen in Africa, played out by whites.

During those first years I spent in Europe, the Spanish obsession with the rest of the continent drew my attention. Commercially, to sell anything, an entrepreneur had to advertise that his merchandise was of European class. Nobody, then, dared to ask what that European class was the goods carried. The ignorance surrounding what was “superior” at the time represented no obstacle, there was no questioning “European class.”

Thus, most Spanish coffee shops and nightclubs were advertised with “European status …” I was very young at that time and, therefore, when visiting European cities, whether they were France, Germany, Switzerland or England, tried to see if those places destined for Spanish leisure had anything to envy of other places in Europe. On the contrary, I would dare to say that I envied holiday destinations in Spain.

From the beginning, I admired the hospitality of the towns and cities in Spain. In any Spanish city or town there were fantastic clubs and cafes. Nightclubs and coffee shops, many of them popular, were of a level that was not seen in the cities of other European cities where I travelled.

This “epidemic” of advertisements in Spain trying to unite themselves with the rest of Europe to be considered of “high category” filled me with confusion. For my part, I wondered why a country like Spain, which is—and was already then—a great power in hospitality, insisted on believing that customers would only go to the cafeteria or to the nightclub if they knew it was on a similar level to the general European. I felt a great ineffectiveness. I wanted to tell the people of Spain that their establishments had nothing to envy from those of their European brothers and neighbors, but I could not. I was just a “poor little black boy” lost in the Eden of whites.

All these contradictions of our world were making me see that the problem was not so much in the races of men, as I have mentioned before, but in the physical and material power that they can exert over each other in any place or determined moment. I was witness, many times, to Spanish complaints at the contempt they received from their European brothers. I even had to comfort some. I understood then that the true drama of man is none other than being poor and weak. I saw a Spanish student bitterly mourn in Zurich (Switzerland): “They take us for animals,” lamented the girl. I approached her and consoled her. The expression “animal,” which one girl used was not even very harsh. The rich and powerful have no other expression for the poor and weak other than that of an animal kept in a zoo. Before I heard the scope of the Spanish woman´s complaints, at the Zurich station I had already heard something similar from my own companion at the time, a Swiss woman. It was Sunday. When we got out of bed I heard her say, while stretching after a long yawn: “Tomorrow, Monday, there will be no choice on the tram but to hold on to those Spaniards and Portuguese who smell like pigs.” I myself also received contempt from some of my own for choosing to study in a country like Spain: “I don´t know how you can study in Spain, they are mean and despicable people …” a cousin once told me in Paris. That cousin had never been to Spain, but for her, everything that represented the Spanish nation resided in its people, who worked in the jobs rejected and despised by the French. I too then, in the eyes of my people, deserved the same contempt and rejection. I had gone to study in a poor country that exported its poor to alleviate their misery…

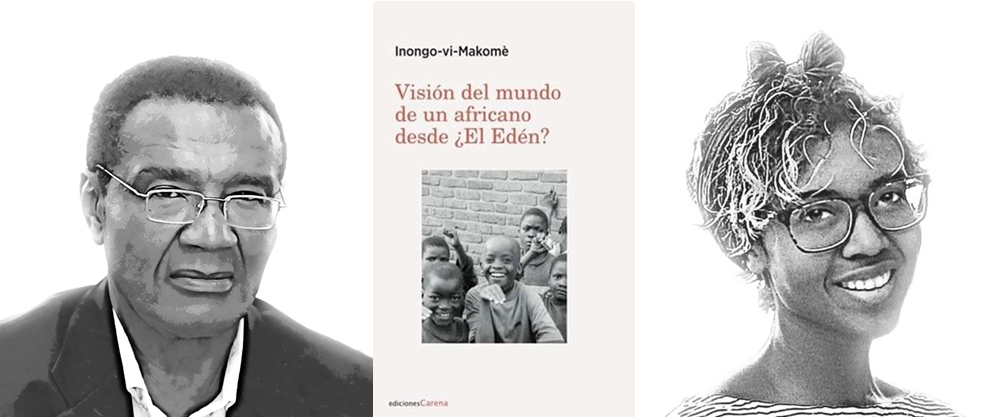

Inongo-vi-Makomè was born in Lobè (Kribi), a town on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in the south of Cameroon. He studied first in Cameroon and finished his studies in Valencia, Spain, where he began his university studies which continued in Barcelona where he still resides. After university, Makomè, dedicated himself to literature. He is a writer, playwright and considers himself mainly to be a story writer because apart from being a teller of stories, all of his works are inspired by the black African oral tradition. Makomè has also written for La Vanguardia, El Periódico de Cataluña, etc. He has also collaborated with the Universidad Autónoma in Barcelona, and given presentations on the theme of immigration in other Universities in Paris and London. His novel, Natives, was translated into English by Michael Ugarte and published by Phonem Media.

Layla Benitez-James is an artist and translator living in Alicante, Spain and serves as the Director of Literary Outreach for the Unamuno Author Series in Madrid. Her poems and translations have appeared in The Acentos Review, Anomaly, Guernica, Waxwing, Revista Kokoro, La Galla Ciencia, and elsewhere. Her audio essays about translation can be found at Asymptote Journal Podcast. Her first chapbook, God Suspected My Heart Was a Geode But He Had to Make Sure was selected by Major Jackson for the 2017 Toi Derricotte & Cornelius Eady Chapbook Prize and published by Jai-Alai Books in Miami in 2018.

[1] [1] Inongo-vi-Makomè España y los negroafricanos. La Llar del Llibre, Barcelona, 1990.

Published on November 8, 2018.