Assessing the Impact of Air Pollution on Students’ Interest in Migration to the European Union: A Study on Students at the University of Macau

This article is funded by the European Studies Undergraduate Paper Prize, awarded by the Council for European Studies.

Air pollution has emerged as the world’s fourth-leading fatal risk to people’s health, causing one in ten deaths in 2013. Each year, more than 5.5 million people around the world die prematurely from illnesses caused by breathing polluted air. A study conducted in 2016 by the World Bank and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington reports that “breathing polluted air increases the risk of debilitating and deadly diseases such as lung cancer, stroke, heart disease, and chronic bronchitis (World Bank Group, 2016, vii). Nevertheless, studies have demonstrated that it negatively impacts students’ performances by causing absenteeism, fatigue, and attention problems (Mohai et al, 2011).

In the last few years, a growing body of research has rediscovered the increasing importance of the environment and recognized it as a driving force for migration. In fact, people’s migration in response to environmental changes is not a new phenomenon. Seasonal migration was mainly practiced by pastoralists and nomads centuries ago (IOM, 2009). The Stern Review (2006), the Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007), and the United Nations Framework on Climate Change (2015), have drawn global attention to the urgency of climate change and its influence on migration. People migrate for a variety of reasons. Scholars identified “push” and “pull” factors, namely economic, political, demographic, social, and environmental (Black et al, 2011). The environment-migration nexus is highly contested and the research debate has taken on two opposite views: a “minimalist view,” which sees environmental factors as indirectly causing migration and interacting with the other drivers; and a “maximalist view,” which advocates a direct causal link between environmental factors and migration (Suhrke, 1994).

This study contributes to the on-going debate by addressing the following research question: to what extent can air pollution be considered a determinant of students’ interest in migration, particularly from Macau to the European Union? The decision to base this thesis on the students at the University of Macau is due to three main reasons. Firstly, it is based on the fact that Macau and the rest of China are the major air pollutants in the world and are the countries which suffer most for their consequences. Indeed, the latter causes 350,000 to 400,000 premature deaths per year (World Bank Group, 2016). Secondly, and strictly related, is the evidence that air pollution has a negative impact on students’ performances (Mohai, et al, 2011). The third reason rests on the fact that China is the country with the largest number of students abroad, 35 percent of whom moved to EU countries in the year 2016 alone, a phenomenon often linked with “brain drain”1 (OECD, 2016). Therefore, it is in the interest of this thesis to add to the “minimalist” or the “maximalist” side of the current debate.

The thesis attempts to answer the research question by conducting a quantitative study, in which, the answers of an online questionnaire are analyzed by means of a correlation and multivariate regression analysis. “Push” and “pull” factors are used to predict interest in migration to the EU, namely education, job prospective, and air quality satisfaction. Overall, the result of the correlations and the multivariate regression show that, despite students being generally unsatisfied with air quality in Macau, air pollution is not the exclusive driver of migration to the EU. Education plays an important role; however, job prospective seems to not be a determining factor in their interest in migrating. While responding to the open-ended questions, other factors contributing to mobility are mentioned, such as family networks. This paves the way to a consideration of other factors, which may be more influential and could be subject of future research. This thesis derives its hypothesis from the theories of Internal and International mobility. Drawing on these, it can be expected that students tend to migrate from more polluted areas to less polluted areas.

The thesis is organized as follows. Firstly, it provides a brief overview of the literature investigating the migration-environment nexus. Secondly, it addresses the theoretical framework deployed to interpret students’ interest in migration to the EU, namely theories of Internal and International migration. The theories help to formulate the hypotheses. Then, the case of Macau is presented, followed by an outline of the methodology. Subsequently, the results of the correlations and multivariate regression analysis are extensively discussed.

Finally, a conclusion addresses the outcome, the limitations of the study, and provides ideas for further research.

Academic Debate on Environment-Migration Nexus

The migration phenomenon is extremely diverse in terms of forms, types, processes, actors, motivations, and geographical context, and it acquires meaning only in a particular historical and social context. For this reason, empirical studies about the environment-migration nexus are interdisciplinary and generally circumscribed to certain areas at a given time (Arango, 2000). Castles (2002) identifies three major inquiries in the debate about environmental migration, two of which serve the interest of this paper: a debate about the definition of “Environmental Refugee”2 (El-Hinnawi 1985; Jacobsen 1988) and a debate about whether environmental factors can be recognized as a root driver of migration. The first scholar to make a clear distinction between these two mainstreams is Suhrke, who (1994) identified a “minimalist view,” which sees environmental factors as indirectly causing migration and mainly interplaying with the other drivers; and a “maximalist view,” which advocates for a direct causal link between environmental factors and migration. Before expanding the debate, it is important to draw a distinction between voluntary migration and forced migration, since the present study entails a certain degree of students’ interest in migration. Speare (1974) states:

In the strictest sense migration can be considered to be involuntary only when a person is physically transported from a country and has no opportunity to escape from those transporting him. Movement under threat, even the immediate threat to life, contains a voluntary element, as long as there is an option to escape to another part of the country, go into hiding or to remain and hope to avoid persecution (89).

Other scholars argue that, even in situations conventionally seen as being voluntary, migration takes place when in fact the migrants have little or no choice. Amin (1974) points out:

A comparative costs and benefits analysis, conducted at the individual level of the migrant, has no significance. In fact, it only gives the appearance of objective rationality to a ‘choice’ (that of the migrant) which in reality does not exist because, in a given system, he (sic) has no alternatives (100).

A third category has been identified by Petersen. It falls between voluntary and forced migration, and entails a certain degree of overlap between the two categories. He distinguishes between “impelled migration when the migrants retain some power to decide whether or not to leave and forced migration when they do not have this power” (Petersen, 1958, 58). Hence, by drawing on this definition, scholars have agreed on considering human migration as “being arranged along a continuum ranging from totally voluntary migration in which the choice and will of the migrants is the overwhelmingly decisive element encouraging people to move, to totally forced migration, where the migrants are faced with death if they remain in their present place of residence” (Hugo, 1996, 105). For the purpose of this paper, air pollution is regarded as a driving force for migration that falls into Petersen’s category of “impelled migration,” since students retain some decisive power on whether or not to move.

According to the “minimalists,” environmental factors mainly interact with other drivers of migration. They define five groups: Economic drivers, such as career opportunities and different income levels; Political drivers, which regard security, persecution, discrimination or public policy; Demographic drivers, which include demographic characteristics of both the sending area and the receiving area, such as size of unemployment among the population or demand for jobs due to an ageing population; Social drivers, namely students’ search for better education, family and cultural expectations; and Environmental drivers, which consist of “rapid-onset” events such as floods, earthquakes, tsunamis or “slow-onset” events such as land degradation, soil erosion, and desertification (Black et al, 2011).

Furthermore, Richmond (1993) argues that migration is in part affected by a series of constraints and facilitators present in the area affected, namely transport networks or family networks. Also, he recognizes that some areas in the world are more vulnerable to environmental disasters than others; hence, more incline to force environmental migration. The factors can be strictly environmental-such as earthquake zones, volcanic zones etc., but also related to the pressure of human activities on the environment, such as exploitation of natural resources, uncontrolled emissions from industries and vehicles etc. – as in the case of China and Macau. Richmond (1993) categorizes air pollution as a Technologically Induced Disaster (TIDs). In the case of China, geography has an important role in northern areas. The mountains that surround the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region do not permit the diffusion of the haze. In the winter, slow air flows, coupled with indoor heating systems relying on coal, tend to worsen the situation (Jia et Wang, 2017).

With regard to students’ mobility and the phenomenon of “brain drain,” several studies have provided evidence that air pollution negatively affects students’ performances, with a special focus on children. This happens by causing absenteeism, as analyzed by Mohai (2011), who found out that, in Michigan, schools located in areas with higher pollution registered lowest attendance rates and highest proportion of students failing educational testing standards. Also, research has demonstrated that air pollution has analogous effects on productivity, fatigue, and memory (Kampa and Castanas, 2008). Graff Zivin and Neidell (2012) found that a change in average ozone exposure results in a substantial decrease in workers productivity. Wang (2009) conducted a study showing that children attending schools in polluted areas attained lower cognitive scores than children attending schools in clearer areas.

Theory: Internal and International Migration

This section focuses on two of the theoretical concepts developed by scholars to describe the migration phenomenon: Internal and International migration. In fact, there is no such a thing as an all-encompassing theory of migration, but the latter can be explained in different ways depending on the geographical, historical, and social context. However, the concepts of Internal and International migration are often deployed to describe trends and characteristics of the phenomenon. By means of these, three hypotheses are articulated.

Internal migration studies analyze the movement of people within their own country, whereas, international migration studies focus on the movement of people across countries. They are characterized by different methods of study. The first discourse about internal migration was conducted by Ernest-George Ravenstein, the undisputed founding father of modern migration theories. He formulated (1885) “The laws of migrations” and observed that people tend to move only short distances from their country of birth, and, strictly linked to this, that this movement mostly takes the form of rural to urban migration. In the sphere of internal migration, on the basis of a micro-level approach, which rests upon individual rational choice, people maximize their expected utility function, and, consequently, the decision of whether to migrate or not is based on a cost-benefit assessment. Considering that air pollution in Macau is less severe than the rest of China, it can be assumed that students tend to move internally, from one heavily polluted area in China to a less polluted area, Macau. Thus, the following hypothesis can be developed:

H (1): There is a positive relationship between students’ satisfaction with air quality and the likelihood to stay in Macau.

International migration can be explained through macro, meso and micro theories. Macro theories emphasize the structural and objective conditions that trigger migration. However, they do not explain why although similar factors exist in more areas in the world, they do not produce the same outcome on mass mobility (Faist, 2000). Meso theories address this limit by rejecting the macro focus and placing migration flows within a system of connections between states (Bilsborrow and Zlotnik, 1994). Two concepts are at the basis of meso theories: systems and networks. Migration is assumed to take place within countries bound by economic, social or political ties. Thus, the triggers of migration are conceived as dynamics taking place between two areas, rather than several indicators. Lastly, micro theories of international migration focus their attention on an individual’s rational choice, which is generally based on a cost-benefit analysis. Among the costs, psychological and financial resources are usually the most considered, whereas, among the benefits of said resources are better salaries and physical safety. The importance of the micro perspective rests on the information it provides about how individuals process the conditions for migrating on a personal level (Faist, 2000). In the case of students at the University of Macau, macro theory is considered, since the aim of the thesis is to assess the importance of air pollution as a determinant of students’ migration, intended as mass-migration. Therefore, the second hypothesis can be developed:

H (2): There is a positive relationship between the importance of air quality to students and their interest in International migration.

This relation between Internal and International migration is a neglected topic in studies of migration. Ronald Skeldon (2006) observed that internal and international migration are becoming increasingly interrelated and they may give rise one to the other. Indeed, individuals may initially decide to move internally and then internationally, or vice versa. There are different types of Internal and International migration: short-distance rural to rural migration flows or rural to urban movements. Yet, they can be regarded as part of a single theoretical framework, in which theories from Internal migration can be associated to International migration and vice versa, as it was already acknowledged by Pryor (1981). It is important to notice that the state is at the core of the distinction and draws the lines between what is internal and what is international by defining borders and empowering its citizens with rights and obligations (Skeldon et al, 2006). Skeldon argues that there is great potential to incorporate studies of internal and international migration both at the empirical and theoretical level, by the combination of return migration (Skeldon, 2008). The present thesis does not address return migration but only estimations of interest in migration. However, by linking Internal and International migration under the common “push” of air pollution, it aims at testing their potential relationship in the light of the recent attempts to bridge the gap between the two carried out by Skeldon. Thus, the third hypothesis can be developed:

H (3): Air pollution leads to internal migration which, in turn, leads to international migration.

These three hypotheses are tested on the case of Macau, in light of the theories and of the variables, whose criteria of selection is clarified in the following chapter.

Data and Method

After the formulation of the hypotheses that guide this study in light of the theory, it is necessary to present the case selection, the data collection method and the methodology. Hence, the present chapter is divided into two sections, which address the case selection and the data collection method, respectively.

Case Selection

This study employs a single case study of Macau, to provide an in-depth understanding of the importance of air pollution as a driver of migration. It focuses on students enrolled at the University of Macau in the academic year of 2016/2017. The choice is based on three criteria. Firstly, the choice of Macau is due to the fact that air pollution is a serious threat to people’s health, as demonstrated by several studies which consider it responsible for 350,000 to 400,000 premature deaths per year (World Bank Group, 2007). The main sources of pollutants are the Pearl River Delta economic zone, the uncontrolled diesel motor vehicles emissions and the power plants. Although the concentration of pollutants in the air varies across the country, with the Southern areas of China suffering less than the Northern areas, China is still the major contributor of air pollution in the world and the country which suffers most from the consequences. The second criterion is based on existing data on students’ International mobility, reporting that China is the country with the largest number of students abroad, with 35% in EU countries in the year 2016 (OECD, 2016). Thirdly, Macau is a suitable case since evidence has shown that air pollution has a negative impact on students’ performances, causing absenteeism, fatigue and concentration problems (Mohai et al, 2011). Considering the high levels of air pollution in Macau, it can be assumed that students’ interest in migration to the EU may be determined by air pollution and its influence on their health and academic performances.

Hence, the empirical relevance of the study becomes evident in two aspects. Firstly, it looks to a case that previous studies have not addressed yet- the Macanese academic and geographical context in relation to students’ mobility is addressed for the first time; secondly, and strictly related, it contributes to the on-going debate between “minimalist” and “maximalists” by adding new evidence to the existing empirical studies. Moreover, the case selection was driven by a personal experience with the severity of air pollution in Macau and the University environment. The fact that air pollution is less severe than the rest of China, yet still considerable, makes it an interesting case to investigate, since it may shed light on potential migration paths, their determinants and the link between Internal and International migration.

Data Collection and Sampling

To assess students’ interest in migration to the EU at the University of Macau an online structured questionnaire was created through the Qualtrics Survey Software and comprises of 21 questions designed to test their satisfaction with air quality in Macau and in the country in which they used to live before moving to Macau, and their interest in migration to the EU. Among the other variables, it also contains questions related to interest in moving to the United States, for the sake of comparability, and the likelihood to stay in Macau, in view of the fact that the results may provide interesting insights on immobility. A final open-ended question is included with the aim of generating qualitative and exploratory data. The target population of the study consists of all students enrolled at the University of Macau in the academic year of 2016/2017. A pilot test was conducted before the official distribution. Four students of the University of Maastricht were provided with the questionnaire in order to test its coherence and validity. The official distribution took place on 24th April 2017 and it was made available to respondents until 15th May, three weeks in total. Ideally, the support of the University staff in spreading the survey through the official webmail would have ensured a larger outreach. However, this could not be provided due to specific rules which do not allow for distribution of material for the purpose of research. Yet, thanks to the support of social media such as WeChat and Facebook the task was facilitated. The questionnaire was posted on the groups of the University residential colleges and those of different faculties: Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FSS), Faculty of Education (FED), Faculty of Arts and Humanities (FAH), Faculty of Law (FLL), Faculty of Health Sciences (FHS), Faculty of Science and Technology (FST) and Faculty of Business and Administration (FBA). Furthermore, since the focus of the thesis is on students, it was ascertained that only students would provide their answer to the questionnaire by clarifying it in the preface.

With regard to H (1), the dependent variable can be found in question 14 and it is the likelihood to stay in Macau, whereas the independent variable is in question 8 and it assesses the satisfaction with air quality in Macau. Their coding is respectively aggregated into 5 groups: 0-Nor likely at all, 1- Not likely, 2-Neither likely, nor unlikely, 3- Likely, 4- Very likely and 0- Not satisfied at all, 1- Not satisfied, 2- Neither satisfied, nor dissatisfied, 3- Satisfied, 4- Very satisfied. With regard to H (2) and H (3), the dependent variable is found in question number 16 and it is the likelihood to move to the EU. Its coding is aggregated into five groups: 0- Not likely at all, 1- Not likely, 2- Neither likely, nor unlikely, 3- Likely, 4- Very likely. Furthermore, the four independent variables that are expected to influence the dependent variable are explained below. Education is mentioned in question 18 as a criterion to consider when moving. The coding is aggregated into five groups: 0- Not important at all, 1- Unimportant, 2- Neither important, nor unimportant, 3- Important, 4- Very important. Air quality and job prospective are respectively mentioned in questions 19 and 20 and their coding is aggregated in the same manner as in question 18. Satisfaction with air quality in the country of living before Macau is coded into five groups, ranging from 0- Not satisfied at all, 1- Not satisfied, 2- Neither satisfied, nor dissatisfied, 3- Satisfied, 4- Very satisfied. Table 1 contains the descriptive statistics of the independent and the dependent variables.

Methodology

The present section outlines the methodology, by virtue of an effective analysis of the results. The overall design of the study will take a quantitative approach, complemented by a qualitative consideration of the results provided by the open-ended question. Taking into account the missing data, a Pairwise Deletion approach is adopted with the aim of minimizing the losses. Also, this technique suits the present study since it ensures valid analysis results with little probability of bias in parameters and estimations, if compared with a Listwise Deletion (Marsh, 1998). The three hypotheses formulated above are analyzed by means of four types of quantitative analysis. Firstly, an assessment of the descriptive statistics is conducted, in order to shed light on the characteristics of the respondents and the general attitudes towards migration and satisfaction with air quality. Secondly, two bivariate correlation analyses with the variables under scrutiny are performed. The first aims at assessing the dependence between the satisfaction with air quality in Macau and the likelihood to stay. This helps to draw conclusion on the theory of internal mobility. The dependent variable can be found in question number 14, which tests the likelihood to stay in Macau, and the independent variable, which can be found in question 8 and tests air quality satisfaction in Macau, of which conclusions can be drawn in relation to the theory of Internal mobility. The second bivariate correlation analysis brings to evidence the dependence between satisfaction with air pollution and likelihood to move to the EU, of which conclusion can be drawn in connection to the theory of International mobility. Both the analyses employ the one-tailed Spearman-Correlation since it allows the measurement of the strength of the relationship between paired data.

The Spearman’s correlation coefficient4 is indicated by rs 5 and is by design constrained as follows:

Thirdly, a multivariate ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression is performed. It serves the interest of this study since it attempts to verify the degree of correlation between the independent variables, and the dependent variable resulting from the second correlation analysis. Moreover, in order to conduct an OLS regression analysis, this study considers the independent variables education and job prospective as continuous and interval variables, hence, there are no big variances in comparison with an analysis with dummy variables (Rhemtualla, Brosseau-Liard & Savalei, 2012). Furthermore, gender and age are also considered in order to control for potential bias in the analysis. The regression equation is thus:

Yi = a + b1 (satisfaction with air quality) + b2 (education) + b3 (job perspective) + b4 (air quality) + b5 (age) + b6 (gender) + ε

4 The closer is rs to +1 or -1 the stronger is the monotonic relationship.

5 The guide for the absolute value of rs :.00-.19 – “very weak”; .20-.39 – “weak”; .40-.59 – “moderate”; .60-.79- “strong”; .80-.1.0 – “very strong”.

Whereby Y is the dependent variable “likelihood to move to the EU”, a is the intercept and b, the independent variables. No value is assigned to the intercept as there is no need for a control variable in this study. Having addressed the methodology, the following chapter of this thesis applies it to the theory and the case study of students at the University of Macau, alongside the three hypotheses.

Empirical Evidence of the Study

This chapter presents the results in relation to the theories set out in the third chapter and compares them with the hypotheses developed. Therefore, it is divided into four sections, beginning with the descriptive statistics of the analyzed sample. Subsequently, the bivariate correlation analyses are discussed, followed by the multivariate regression analysis to ensure a coherent analysis of air pollution as a driver of students’ interest in migration to the EU.

Descriptive Statistics of the Respondents

This section looks at the characteristics of the respondents to the questionnaire and remarks important factors that help to address the hypotheses. Also, the general attitudes towards air pollution and environmental protection are assessed.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of the analysed sample

| Characteristics | Percent | N |

| Gender | 340 | |

| Male | 29, 2% | |

| Female

Age 16-20 |

69, 2%

56, 4% |

349 |

| 21-25 | 34, 7% | |

| 26-30 | 6, 9% | |

| 31+

Years of study at Umac Less than one year |

2, 0%

19, 5% |

349 |

| 1 year | 27, 5% | |

| 2 years | 26, 1% | |

| 3 years | 14, 0% | |

| 4 years or more

Country of birth Macau |

12, 9%

35, 0% |

339 |

| Mainland China | 49, 6% | |

| Other Asian country | 7, 4% | |

| European Country EU | 1, 4% | |

| European Country (other) | 0, 0% | |

| Other

Country of residence before Macau Macau |

3, 7%

44, 4% |

335 |

| Mainland China, Beijing area | 2, 9% | |

| Mainland China, urban area | ||

| (Other than Beijing area) | 35, 0% | |

| Mainland China, rural area | 4, 0% | |

| Another Asian country | 7, 2% | |

| Another non-Asian country | 2, 6 % | |

| Concern with air pollution and | ||

| environmental protection | 331 | |

| Very concerned | 26, 89% | |

| Concerned | 55, 89% | |

| Neither concerned, nor unconcerned | 13, 60% | |

| Not concerned | 3, 32% | |

| Not concerned at all | 0, 30% |

The total number of respondents to the questionnaire is 349. At first glance, it can be seen that the percentage of female respondents is notably higher than the percentage of male respondents. This may be due to a disparity in the total number of female and male students enrolled at the University of Macau in the year under investigation. As a matter of fact, according to the data reported by the Registry of the University of Macau, the total number of students registered in 2016/2017 is 9, 987 comprising of 5,724 females and 4, 263 males (Registry, 2017). Therefore, the following multivariate analysis considers also gender as a variable, in order to control for possible gender bias in migration. Furthermore, the results provide support for the analysis of the first hypothesis. It can be noted that 35% of the respondents was already living in Macau, whereas a significant 49% of the respondents was born in Mainland China and a 42% has lived there until moving to Macau. This data shows an internal mobility trend, from urban to urban areas, which is in clear contrast with Raventein’s observation of a tendency to move from rural to urban areas. A cumulative 83% of the respondents feel concerned with air pollution and environmental protection, which could signify a potential attitude to consider air quality in their migration plans. On the basis of these results, the following section focuses on the correlation analyses.

Bivariate Correlations

Having assessed the general characteristics of the respondents and the general attitudes towards air pollution and environmental concern, this thesis now turns to the presentation of the bivariate correlation analyses, comparing the outcome with the initial hypothesis. Firstly, H (1) is evaluated, which argues that there is a positive relationship between students’ satisfaction with air quality and the likelihood to stay. It means that the more students are satisfied with air quality in Macau, the more likely they are to stay. Considering that the 49 % of the students comes from Mainland China, thus, has already moved internally, a trend of internal mobility is apparent. Yet, the bivariate correlation analysis provides a confirmation or a rejection of the hypothesis and evaluates the role played by air pollution. Table 3 reports the output of the bivariate correlation between the independent variable and the dependent variable.

| Independent variable | N | Dependent variable |

|

Satisfaction with air quality in Macau |

349 |

Likelihood to stay in Macau Correlation Coefficient rs

,112* |

| Note: * p< ,01; ** p <, 05; *** p < ,001 |

Table 3: Correlation between air quality satisfaction in Macau, and likelihood to move to stay in Macau.

The result of the Spearman correlation highlights a positive, significant relationship between students’ satisfaction with air quality in Macau and the likelihood that they will stay. This means that the more students are satisfied with air quality, the higher is their interest in staying, and confirming that air pollution can be one determinant of Internal migration H (1). However, the relationship between the two variables is weak; thus, other factors may play a role in dynamics of Internal migration, which are not discussed since they go beyond the scope of this study. Next, H (2) is evaluated. The answer category “Very important” is assumed to show a strong relation with students’ interest in migration to the EU, whereas “Not important at all” is assumed to show no relation with students’ interest in migration to the EU. Table 4 reports the output of the bivariate correlation between the four independent variables and the dependent variable.

| Independent variable | N | Dependent variable |

| Likelihood to move to the EU | ||

| Correlation Coefficient rs | ||

| Air quality satisfaction in | ||

| the country before Macau | 307 | , 018 |

| Importance of education as a driver of migration |

307 |

, 187** |

| Importance of air quality as a driver of migration |

302 |

, 177** |

| Importance of job prospective as a driver of migration |

300 |

, 033 |

|

Note: * p< ,01; ** p <, 05; *** p < ,001 |

Table 4: Correlation between air quality satisfaction, education, air quality, job prospective and likelihood to move to the EU.

In order to address the extent to which internal migration may then lead to International migration due to air pollution (H (3)), it is necessary to take a closer look to the independent variable “air quality as a driver of migration”. It represents an assessment of the general importance of air pollution in students’ interest in migration to the EU. As it becomes evident after running the Spearman’s correlation a weak positive relationship is found, meaning that the more important air quality is considered to be, the more students are likely to move to the EU. Hence, this finding is consistent with the second hypothesis. This outcome is also displayed in the crosstabs6, which show the degree of importance, ranging from “not important at all” to “very important” and the likelihood of moving to the EU, ranging from “not likely at all” to “very likely”. Considering the results of the correlations between the other two independent variables “importance of education” and “importance of job prospective”, two considerations can be made. The first variable, education, is also positively and weakly correlated with the dependent variable, meaning that the more students’ regard education as an important factor, the more likely they are to move to the EU. The fact that the EU was considered by Chinese students a popular destination for higher education was already confirmed by the existing data on student mobility (OECD, 2016). However, the evidence here presented relates to estimations of potential future migration paths, based on the fact that it tests students’ interest in migration after the obtainment of their University degree. It can therefore be argued that the EU is an attractive destination for study purposes.

However, it needs to be acknowledged that the questionnaire does not address specific questions about the estimated time of permanence, thus, relevant concepts such as seasonal, temporary or permanent migration cannot be investigated.

However, the third independent variable “importance of job perspective” may shed light on these concepts in the view of the findings. Surprisingly, Spearman’s correlation has revealed that no significant relation can be found between the independent variable and the likelihood to move to the EU, meaning that students’ interest in migration is not prompted by the prospective of a job or a career. This finding is probably one of the most remarkable, since it contradicts the fundaments of migration theories, which regard economic factors as the most influential drivers of migration. The first theoretical explanation based on job-seeking was provided in the third quarter of the twentieth century by Arthur Lewis’ model of “Economic Development with Unlimited Supply of Labour”. He estimated that wage differentials between two sectors would foster workers’ migration (Lewis, 1954). Also, the Neoclassical theory viewed the origin of migration in the disparities in wage rates between countries, which in turn reflect income and welfare disparities, entailing in its paradigm concepts of rational choice, utility maximization and net returns. In the last quarter of the twentieth century the “new economics of labor migration” developed, primarily as a critique to the precedent school of thoughts arguing that migrants aim at maximizing income, but move also relatively to their reference group that is their family or household members in general (Stark, 1991). It is followed by the “Dual Labour Market theory” developed by Michael Piore (1979), which rests not only on economic determinants but underlines the importance of macro-level structural factors in migration. Finally, “World System theory” remarks the importance of linkages between countries at different stages of development (Arango, 2000). In the light of this brief overview on the founding migration theories, it seems evident that job prospective has always played an essential role in International migration.

However, an explanation for these findings can be embedded in return migration studies. Instead of making use of the educational skills acquired abroad, students may prefer to return to their home county to work. Rosenzweig (2006), for instance, investigated higher education and international migration in Asia and identified a “brain circulation”, whereas Dustmann, Fadlon and Weiss (2010) attributed the creation of “brain gain” to return migration (i.e. when students returning bring to the home country augmented local skills). Therefore, although this thesis accepts H (2), it also acknowledges the fact that air pollution is not the exclusive driver of students’ interest in migration to the EU. Hence, a multivariate regression analysis becomes necessary and is presented in the following section.

Multivariate Regression Analysis

Having performed the bivariate correlations, it is now in the interest of this analysis to conduct the multivariate regression. This highlights the interdependence of all the independent variables, namely education, job prospects, air quality and satisfaction with air pollution, on the dependent variable, that is likelihood to move to the EU. Also, gender and age are considered, with the aim of controlling potential bias. It can therefore be regarded as a deepening of the analysis of H (2).

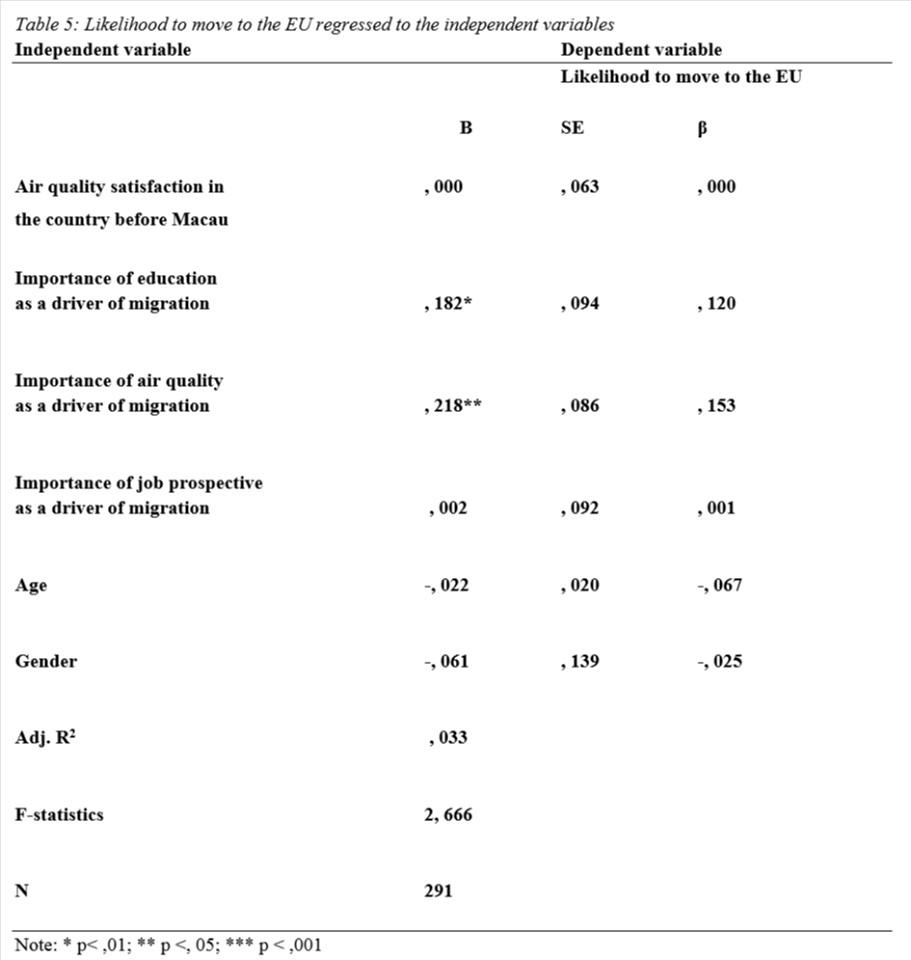

Table 5 displays the most relevant elements of the regression. Firstly, it needs to be noted that the value of the adjusted R2 is low, meaning that there is a limited number of explanatory factors due to a limited number of control variables that are taken into consideration in the equation. However, this does not condition the validity of the study (Frost, 2013).

Furthermore, collinearity is not present, as shown by the fact that the variance inflation factor is below the threshold of three in all the cases. Also, the regression analysis entails explanatory power, since it finds that air quality satisfaction, education, job prospective, air quality in general, age and gender account for a significant amount of the variance in the likelihood to move to the EU. As far as gender and age are concerned, the result of the regression shows that they do not significantly influence the outcome variable in relation to the other variables considered. With regard to education, the analysis demonstrates to be highly significant. Hence, education is undoubtedly a determinant of students’ interest in migration to the EU. Air quality as a driver of migration also proves to be statistically significant, meaning that students take into account the environmental factor when moving to the EU. On the other hand, the satisfaction with air quality in the country of living before Macau and job perspective does not prove statistically significant. This confirms the results of the correlation analysis set out in section 5.2.

Therefore, drawing on the multivariate regression, it can reasonably be argued that Internal migration leads to International migration under the “push” of air pollution, but, the latter is not the sole determinant of migration, confirming H (3) and placing this study on the “minimalist” side of the debate. In other words, environmental factors can be seen as a contributor to students’ interest in migration to the EU, but they act in relation to other factors. Surprisingly, the study has revealed that job prospects in Europe are not appealing to students at the University of Macau. This may be caused by other factors. Thereof, the open- ended question seems to provide relevant insights. Family networks have been mentioned as an important factor: “I don’t want to go anywhere because my family is all in Macau and air pollution doesn’t change my choice” (On-line questionnaire: Assessing the impact of air pollution on students’ interest in migration at the University of Macau, 2017). These findings can be embedded in macro theories of international migration. Networks have a significant influence on destinations and the volume of migration. They help to facilitate mobility due to sharing of information, contact, financial and social support, contributing to the phenomenon of mass migration (Faist, 2000). In the case of the respondent, they cause immobility. Due to the difficulty in identifying which factors may have significant impact on interest in migration, the need for further research arises, to deepen the understanding of determinants of students’ migration to the EU. Furthermore, considering that the present study is based on estimations of interest in migration, it might be in the interest of future research to confirm whether they took place, or, other factors intervened in the meanwhile.

Conclusion

The present thesis investigated to what extent air pollution can be considered a determinant of students’ interest in migration, particularly from Macau to the European Union. The analysis was based on an-on line questionnaire, comprising of questions aimed at assessing students’ interest in migration and concern with the environment. A quantitative approach was adopted by means of two correlation analyses and a multivariate regression analysis. The results generally show that air pollution can be considered a determinant of migration, but, other factors such as education and family networks play also a role in students’ interest to move to the EU. Therefore, this thesis contributes to the debate between “minimalists” and “maximalists,” demonstrating that air pollution has an impact on students’ interest in migration to the EU, but, it is not the only driver. Rather, other factors, such as education and family network, play a more significant role. Hence, it adds to the “minimalist” side of the debate, which considers environmental factors as mainly interplaying with other drivers. The three hypotheses that guided the analysis were generated on the basis of theories of Internal and International migration. With regard to the first hypothesis, the analysis shows that the more students are satisfied with air quality in Macau, the higher is their interest in staying.

This confirms that air pollution can be one determinant of internal migration. The second hypothesis aimed at assessing students’ interest in international migration, specifically to the EU. The results demonstrate that air pollution plays a significant role in driving migration to the EU, next to education. Specifically, the more students consider air quality as an important factor the more likely they are to move to the EU, highlighting a positive relationship between the variables, which confirms the second hypothesis. Surprisingly, job prospective is not appealing to students. This finding shows a change in the migration trend in respect to the literature tradition, where economic factors played a major role in driving migration.

However, in both correlations, air pollution has a weak relationship with the dependent variables, hence, the multivariate regression analysis helped to further examine these findings by adding other variables such as gender and age in order to control for potential bias. The result of the multivariate regression confirms that air pollution can be considered a driver of migration to the EU, among the other factors under scrutiny, thus linking internal migration with International migration and confirming the third hypothesis.

Finally, the answers to the open ended questions offered interesting inputs for the consideration of other factors such as family networks, which seem to play a role in return migration. Therefore, in terms of EU migration challenge, the study suggests that students are interested in migrating to the EU for study purposes, and, air pollution plays an important role. However, they are not considering the prospective of a job, but rather mention family networks as an important factor. A reflection about the limits of the study needs to be conducted. Firstly, since the study tests interest in migration, the on-line questionnaire is not specific about seasonal, temporary or permanent migration. However, this approach does not attempt to foresee paths of migration in greater details, but to understand whether the interest is present. Also, with regard to the method, the imbalance in gender data might be addressed more accurately by means of a stratified analysis, thus, generating two different models, for females and males students respectively. In any case, the method used in the present thesis does not bias the results.

To overcome the limitations and further elaborate on its findings, future research needs to be conducted. In particular, it is of great importance to assess the shift of interest in migration, traditionally associated with job prospective, in order to understand what the implications are on the sending country and the receiving country. This might shed a new light on the phenomenon of “brain drain”. Also, it might be of great interest to conduct a similar study in other areas of China which are more affected by air pollution, such as Beijing. Student’s interest in migration may be stronger not only due to the severity of air pollution but also in relation to other factors pertaining to the different political and economic context. Yet, it has to be remarked that air pollution has an influence on migration, and, being a serious threat to people’s life, it may pose a further migration challenge to the EU in the near future.

Evelin Rizzo graduated from Maastricht University with a Bachelor’s Degree in European Studies in 2017 and is currently undertaking a Master of Arts in Human Rights and Democratization. Her academic interests range from the EU migration challenge to environmental sustainability and the promotion of women’s rights. The exchange semester at the University of Macau inspired her essay “Assessing the Impact of Air Pollution on Students’ Interest in Migration to the European Union: A Study on Students at the University of Macau,” which has been selected as a winner of CES’s 2018 Undergraduate Project Prize.

This article is funded by the European Studies Undergraduate Paper Prize, awarded by the Council for European Studies.

References:

Amin, S. (1974). Modern Migrations in Western Africa. Oxford University Press: London.

Arango, J. (2000). Explaining Migration: A Critical View. International Social Science Journal, 52 (165), 283-296.

Bailey, A. (2005). Making Population Geography. Hodder Arnold: London.

Bilsborrow, R. E., Zlotnik, H. (1994). The Systems Approach and the Measurement of the Determinants of International Migration, Paper presented at the Workshop on the Root Causes of International Migration, Luxembourg, 14 -16 December.

Black, R., Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., Dercon, S., Geddes, A., and Thomas, D. (2011). The Effect of Environmental Change on Human Migration. Migration and Global Environmental Change, 21(1), S3–S11.

Castles, S. (2002). Environmental Change and Forced Migration: Making Sense of the Debate. New Issues in Refugee Research, Working Paper No. 70, United Nations High Commission for Refugees, Geneva.

Dustmann, C., Fadlon, I., Weiss, Y. (2010). Return migration, human capital accumulation and the brain drain. Journal of Development Economics, 95 (2011), 58-67. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctpb21/Cpapers/DustmannFadlonWeiss2011.pdf

El-Hinnawi, E. (1985). Environment Refugees, Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environmental Programme.

Faist, T. (2000). The Volume and Dynamics of International Migration and Transnational Social Spaces. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Frost, J. (2013). Regression Analysis: How do I interpret R-squared and Assess the Goodness- on-Fit? The Minitab Blog. Retrieved June 9, 2017, from http://blog.minitab.com/blog/adventures-in-statistics-2/what-is-the-f-test-of-overall- significance-in-regression-analysis

Geddes, A., Adger, N., Arnell, N., Black, R., Thomas, D. (2012). Migration, Environmental Change and the Challenges of Governance. Environment and Planning C, 30(6), 951- 67.

Geddes, A., Jordan, A. (2012). Migration as Adaptation? Migration and environmental governance in the European Union. Environment and Planning C, 30(6), 1029-44.

Graff Zivin, J., Neidell, M. (2012). The Impact of Pollution on Worker Productivity. American Economic Review, 102(7), 3652–3673. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic1459278.files/2015_2- 20_Matt%20Neidell_1- Paper_Impact%20of%20Pollution%20on%20Worker%20Productivity.pdf

Hugo, G., J. (1996). Environmental Concerns and International Migration. International Migration Review, 30(1), 105–131.

International Organization for Migration (2017). Key Migration Terms, Glossary on Migration, International Migration Law Series No. 25, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2017, from https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms

International Organization for Migration (2015). Global Migration Trends Factsheet 2015. IOM’s Global Migration Data Analysis Center GMDAC. Retrieved May 16, 2017, from https://publications.iom.int/system/files/global_migration_trends_2015_factsheet.pdf

International Organization for Migration (2009). Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Assessing the Evidence. Retrieved May 16, 2017, from http://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/migration_and_environment.pdf

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptations and Vulnerability. Retrieved on 16, May 2017 from https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg2/ar4_wg2_full_report.pdf

Jia, H., & Wang, L. (2017) Peering into China’s thick haze of air pollution: Scientists are teasing out which emissions contribute most and the chemical reactions that create smog filled with particulates. C&EN, 95(4), 19-22. Retrieved May 16, 2017, from http://cen.acs.org/articles/95/i4/Peering-Chinas-thick-haze-air.html

Kampa, M. and Castanas, E. (2008). Human health effects of air pollution. Environmental Pollution, 151(2), 362–367. Retrieved May 16, 2017, from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749107002849

Lewis, A., W. (1954). Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour. The Manchester School, 22 (2), 139–191.

Marsh, H. W. (1998). Pairwise deletion for missing data in structural equation models: Non positive definite matrices, parameter estimates, goodness of fit, and adjusted sample sizes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 5(1), 22-36.

Mohai, P., Kweon, B.-S., Lee and Ard, K. (2011). Air Pollution Around Schools is Linked to Poorer Student Health and Academic Performance. Health Affairs, 30(5), 852-862.

Morton, K. (2014). Policy Case Study: The Environment, in Joseph, A., W., Politics in China: An Introduction, Second Edition, Oxford University Press.

OECD (2016). Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Retrieved June 4, 2017, from http://www.oecd.org/edu/education-at-a-glance- 19991487.htm

Petersen, W. A. (1958). A General Typology of Migration, American Sociological Review, 23 (3), 256-266.

Piore, M. J. (1979). Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor Industrial Societies. Cambridge University Press. New York.

Pryor, R.J. (1981). Integrating international and internal migration theories, in Kritz, M. M., Keely, C. B. and Tomasi, S. M. (eds) Global Trends in Migration:Theory and Research of International Population Movement. USA: Center for Migration Studies, 110-29.

Ravestein, E., G. (1885). The Laws of Migration. Journal of the Statistical Society of London, 48 (2),167-23. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from https://cla.umn.edu/sites/cla.umn.edu/files/the_laws_of_migration.pdf

Registry (2017). Registered Students: Total No. of Registered Students in 2016/2017 (by headcount)(as at 18 November 2016). University of Macau. Retrieved June 16, 2017, from https://reg.umac.mo/qfacts/y2016/student/registered-students/

Rhemtualla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P., & Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17 (3), 354- 373.

Richmond, A. (1993). The Environment and Refugees: Theoretical and Policy Issues. Revised version of a paper presented at the meetings of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, Montreal.

Rosenzweig, M. (2006). Higher education and international migration in Asia: brain circulation. Higher Education and Development. In: edited by Justin Yifu Lin and Boris Pleskovic (Eds.), Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics Regional, The World Bank, Washington, DC. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTABCDE2007BEI/Resources/MarkRosenzweig ConferenceVersion.pdf

Skeldon, R., King, R., Vullnetari, J. (2008). Internal and International Migration: Bridging the Theoretical Divide, Working paper 52. Sussex Center for Migration Research, University of Sussex.

Skeldon, R. (2006). Interlinkages between Internal and International Migration and Development in the Asian Region. Population, Space and Place, 12, 15-30. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from https://www.unescogym.org/wp- content/uploads/2015/12/Skeldon_2006_Interlinkages-between-Internal-and- International-Migration-Asia.pdf

Speare, A. (1974). The Relevance of Models of Internal Migration for the Study of International Migration, in G. Tapinos (Ed.) International Migration: proceedings of a Seminar on Demographic Research in Relation to International Migration, CICRED, Paris, pp. 84-94.

Suhrke, A. (1994). Environmental Degradation and Population Flows. Journal International Affairs, 47 (2), 12-17. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-15144563/environmental-degradation- and-population-flows

Stern, N. (2006). Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change. HM Treasury, London.

Retrieved June 4, 2017, from http://mudancasclimaticas.cptec.inpe.br/~rmclima/pdfs/destaques/sternreview_report_ complete.pdf

Stark, O. (1991). The Migration of Labor. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2015). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved May 16, 2017, from https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf

Wang, S., Zhang, J., Zeng, X., Zeng, Y., Wang, S., and Chen, S. (2009). Association of Traffic related Air Pollution with Children Neurobehavioral Functions in Quanzhou, China. Environmental health perspectives, 117(10), 1612-1618. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2790518/

World Bank Group (2016). The Cost of Air Pollution: Strengthening the Economic Case for Action. University of Washington, Seattle. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/781521473177013155/pdf/108141- REVISED-Cost-of-PollutionWebCORRECTEDfile.pdf

Published on October 2, 2018.