An introduction to our special feature on Radicalism and Violence in Europe.

Several intertwined issues animate discussions of radicalism and violence in Europe today. On the one hand, individual countries, as well as the European Union more broadly, have been preoccupied with the prevention of radicalization to Islamist extremism and interrupting planned violence on European soil, as well as the flow of recruits of foreign fighters to the Islamic State. On the other hand, violence from far right extremists—and increasing support for far right parties across Europe—has escalated, most recently in the dramatic street protests in Chemnitz, Germany, where 6,000 far right marchers took to the streets to protest “criminal immigrants” amid scenes of harassment and attacks of non-ethnic Germans, journalists and counter-protesters.

This most recent example from Germany is just one among many other issues regarding radicalism in contemporary Europe. September elections to the national parliament in Sweden also gained much international attention. While the far right Sweden Democrats increased the number of seats in the Riksdag by thirteen and became the third strongest party in the recent national elections, the party did not get the landslide victory some observers had predicted. Like the presidential elections in France in May 2017 when Marine Le Pen got 33.9 percent in the second round with Emmanuel Macron defeating her clearly, one might say that it could have been worse. And even if one takes into consideration the post-election crisis that hit the Rassemblement National, formerly known as the Front National, one cannot escape the fact that far right and ultra nationalist political forces are gaining ground in several European countries and that their political profile is supported by significant portions of particular national populations.

Twenty years ago, it was an exceptional situation for far right parties to become part of a ruling coalition. The coalition between the Austrian Peoples Party (ÖVP) and the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) in February 2000 led to fierce reactions by the international community, including sanctions by fourteen EU member states. More recently, the number of governments with a significant national conservative and anti-immigrant profile such as Italy and Austria has grown significantly. In Poland and Hungary, right-wing governments have even pushed through constitutional changes that damage democratic principles fundamentally. Especially in view of such developments, scientific analysis and systematic research are indispensable to understand and to confront political tendencies that undermine democracy and human rights. For this reason, our special issue on Radicalism and Violence is heavily—though not exclusively—focused on radical right-wing radicalism.

In this special issue, artists and authors take up these issues in a series of feature essays and works, short opinion pieces, and research reports, examining questions of radicalism and violence, prevention and intervention, and radicalization and de-radicalization across Europe and other parts of the world. The authors examine cases from Germany, France, Hungary, the U.K. and beyond, looking at social media, school-based interventions, the use of history by far groups, the role of public intellectuals, and more.

In one of the feature essays, Aude Jehan-Robert analyzes the rise of populism and violent extremism in France over the past several decades, tracing tensions in identity politics and the impact of long-term feelings of marginalization among France’s Muslim communities, which represent the largest Muslim population in Europe. Describing trends including political leaders’ declarations of multiculturalism’s failure, state polices banning headscarves, growing anti-immigrant and anti-Islam sentiment among the general public, and the impact of the Paris 2015 terror attacks on recorded acts of racism and Islamophobia, Jehan-Robert explains the underlying developments that have contributed to voters’ frustration, anger, and criticism of traditional French political parties and the rise in support for Marine Le Pen and the far right more broadly. In the second half of her essay, Jehan-Robert describes President Macron’s new strategy to counter radicalization and fight terrorism, called “Prevent to Protect.”

Raymond G. Slot, Frans Van Assche, Sergio Vieira, and Joanna Vieira dos Santos’ research report showcases the results of their research examining the effects of an European Commission-funded, school-based radicationalization prevention initiative focused on transcendental meditation (TM), which aims to support young people’s social inclusion and develop psychological traits that counter terrorist characteristics. Slot et. al. studied five schools in Sweden, The Netherlands, and Portugal who had introduced Quiet Time (a TM program) into their curriculum by adding 30 minutes per day of student silent meditation. Findings showed that students who practiced TM experienced reduced anxiety, increased cooperation with others, higher flexibility and improved ability to express feelings and eneds. Results also showed positive effects for teachers who practiced TM, with reduced emotional exhaustion, lower anxiety and stress, and higher enthusiasm and psychological well-being. TM, the authors argue, may be an effective early intervention to build resilience among young people and prevent radicalization toward extremism and terrorism

Tom Pettinger’s feature essay examines the controversial Prevent program in Great Britain, focusing in particular on the Channel program within Prevent, which provide mentoring and intervention to referred individuals deemed most at risk for violence. Since 2015, public officials such as teachers, physicians, social workers and nurses are legally obligated to report students or clients who they feel are at risk of radicalization. The “most purportedly dangerous” of these referrals move into the Channel program. Despite Channel interventions being lauded in public narratives as “helping to save lives,” Pettinger argues that the Channel cases have little to do with national security and are, by and large, banal and not linked to true threats. The securitization of dangerous opinions, this essay argues, lacks both scientific rigor and external oversight, and is aimed at population management rather than protection.

Julian Göpffarth’s essay turns to the recent case of the new far right in Dresden, Germany, examining compelling questions about the role of local and global intellectuals in shaping the public’s understandings of nationalist and universalist ideas, views on immigration and migration, and assumptions about belonging. The new German right, Göpffarth compellingly shows, has strategically developed not only national but also local intellectuals who play a significant role in shaping public debate and ideas about pressing social issues in ways that help radicalize the mainstream. These local intellectuals include bookshop owners, local businessmen and academics who aim to provide what Göpffarth calls a new right “counter-culture” and intellectual legitimation for far right ideas.

Sam Jackson looks at how far right groups and parties use national history as a specific tactic to help them recruit, mobilize and radicalize supporters: talking about national history. Historical heroes and national myths help far right leaders establish extreme ideas as politically and morally legitimate, Jackson argues. Framing contemporary conflicts as similar to historical ones is thus a strategic choice that helps far right actors achieve their goals. Thus, the U.S. far right Oath Keepers frame contemporary political conflicts as an extension of the revolutionary struggle for American independence, arguing that resisting the federal government is an act of patriotism even if it leads to war and violence. However, Jackson points out, this rhetorical strategy does not work for far right groups in all countries. Moreover, only selected parts of any given nation’s past are effective sources for the far right to draw on—with the German case a clear example of how the far right draws on some aspects of the German past but not others. Finally, Jackson argues, the success of the strategy relies in great part on understandings of national history among the populace more broadly.

The six short opinion essays by Chris Allen, Bernhard Forchtner, Katherine Kondor, Barbara Manthe, Rob May, and Lella Nouri take up a range of issues including the rise of the Reichsbürger movement in Germany—a sovereign citizen movement involving over 16,000 German citizens who reject the legitimacy of the federal German government; the ways that far right groups in the U.K. draw on mainstream language about liberty, ‘Enlightenment values’ and free speech; the ongoing popularity of hate music and white power music; radical and far right perspectives on environmental issues; the landscape of the radical right in Hungary; and how Facebook’s banning of the far right group Britain First has affected its popularity in the social media space.

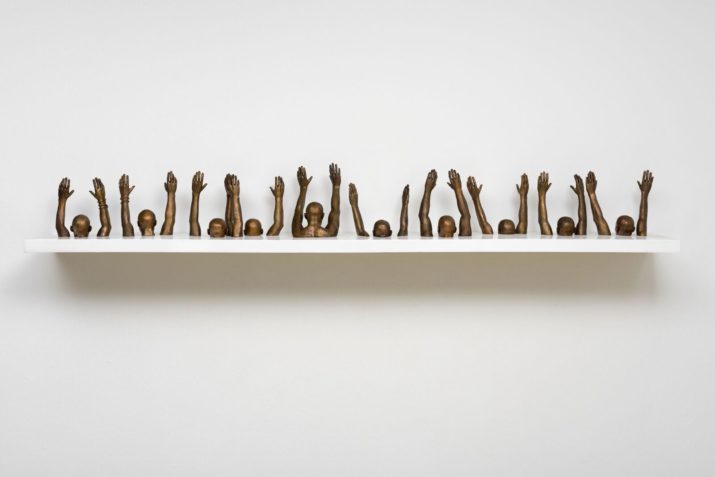

Lastly, the artists in our visual art feature “(G)UNSAFE,” Hank Willis Thomas and Yosman Botero, use their personal experiences with racial inequality and terror, as well as issues of gun violence, to call awareness to racism and police brutality. In 2000, Thomas’ best friend and cousin was murdered for a piece of jewelry outside a Philadelphia night club. The fact “that someone could be killed over a tiny commodity” did not let Thomas rest, and he felt determined to challenge our commodity culture and its resulting greed juxtaposed against the promise of a Mastercard slogan.Yosman Botero depicts the violence in his birthplace, Cúcuta, a Colombian city situated on the border to Venezuela, that has been a hub for a multitude of criminal activities: a transshipment point for drugs, contraband smuggling, arms trafficking and illegal mining.

The overall situation and dynamic in the many different countries across Europe are not shaped by identical factors. Some countries are better off economically than others, and some have a longer history of immigration, for example. But it is clear that elections campaigns for the European parliament end of May 2019 will bring one of the next important challenges to hedge in radical right and anti-immigrant forces all over Europe. It is our hope that the insights offered through the essays in this special issue of Radicalism and Violence will contribute to informed debate and discussion about the varied issues motivating the rise of radical and violent groups and parties across Europe.

Cynthia Miller-Idriss is Professor of Education and Sociology in the College of Arts and Sciences and Director of the International Training and Education Program in the School of Education at American University. Professor Miller-Idriss earned her bachelor’s degree from Cornell University, and an MA in Sociology, an MPP in Public Policy, and a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Michigan. Her current research follows two main trajectories, focused on the internationalization of higher education in the U.S., and education and far right wing youth culture in Germany.

Nicole Shea is the Director of the Council for European Studies at Columbia University and the Executive Editor of EuropeNow.

Fabian Virchow is Professor of Social Theory and Theories of Political Action at the University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf where he also directs the Research Unit on Right Wing Extremism. He has published numerous books and articles on worldview, strategy and political action of the far right.

Research

– “‘We Are Patriots’: Uses of National History in Legitimizing Extremism” by Sam Jackson

– “Everyday Securitization: Prevention and Preemption in British Counter-Terrorism” by Pettinger

Commentary

– “Britain First: Banned on Facebook but not Solved” by Lella Nouri

– “Protecting the Natural Environment? A Look at the Radical Right” by Bernhard Forchtner

– “Mapping the Radical Right in Hungary” by Katherine Kondor

– “Defending Free Speech: A New Front for Resisting Islamifcation” by Chris Allen

– “Just Harmless Lunatics? The Reichsburger Movement in Germany” by Barbara Manthe

– “Hearing Hate: White Power Musi” by Rob May

Review

– The Extreme Gone Mainstream, reviewed by Bart Bonikowski

Campus Spotlight: American University

– “Syllabus: Terrorism, Extremism, and Education” by Cynthia Miller-Idriss

– “The Radical Right in the Global Context” by Cynthia Miller-Idriss

Visual Art

– “(G)UNSAFE,” an art series curated by Nicole Shea

Photo: Raise Up, 2014 © Hank Willis Thomas. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Published on October 2, 2018.