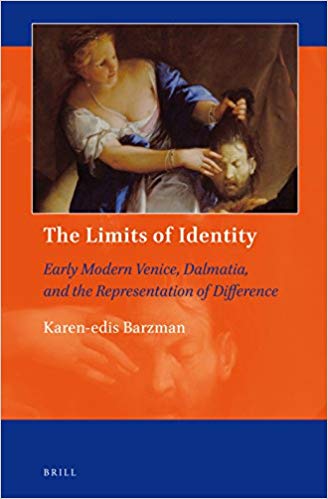

The Limits of Identity: Early Modern Venice, Dalmatia, and the Representation of Difference by Karen-edis Barzman

Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople, hosted at his court the Venetian painter Gentile Bellini, brother of the sublime master Giovanni Bellini. Gentile produced some fascinating paintings of Ottoman figures, including the beautiful watercolor painting of the “Seated Scribe” in the Isabella Steward Gardner Museum in Boston—writing with intense concentration—but, most importantly, the bearded and turbaned portrait of Mehmed himself in the National Gallery in London. Mehmed was keenly interested in the culture of the Italian Renaissance and glad to have Bellini visiting his court, while the Venetian Senate also sponsored the visit as a part of its Ottoman policy. According to a famous anecdote, when Bellini painted the decapitated head of John the Baptist, Mehmed was critical of the picture for its failure of verisimilitude: as a battle-hardened warrior he felt that the civilian Bellini was too unworldly to know what a decapitated head really looked. The sultan therefore—as the story goes—commanded the beheading of a slave in order to give the painter a visual template for future reference. “Se non è vero, è ben trovato,” the Italians say: “If it’s not true, it’s well-conceived.” That would certainly be the case for this unprovable anecdote: well-conceived inasmuch as Mehmed was a warrior, and had some experience of bloodshed, while Bellini, as a Renaissance painter, would have recognized anatomical verisimilitude as something worth striving for.

Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople, hosted at his court the Venetian painter Gentile Bellini, brother of the sublime master Giovanni Bellini. Gentile produced some fascinating paintings of Ottoman figures, including the beautiful watercolor painting of the “Seated Scribe” in the Isabella Steward Gardner Museum in Boston—writing with intense concentration—but, most importantly, the bearded and turbaned portrait of Mehmed himself in the National Gallery in London. Mehmed was keenly interested in the culture of the Italian Renaissance and glad to have Bellini visiting his court, while the Venetian Senate also sponsored the visit as a part of its Ottoman policy. According to a famous anecdote, when Bellini painted the decapitated head of John the Baptist, Mehmed was critical of the picture for its failure of verisimilitude: as a battle-hardened warrior he felt that the civilian Bellini was too unworldly to know what a decapitated head really looked. The sultan therefore—as the story goes—commanded the beheading of a slave in order to give the painter a visual template for future reference. “Se non è vero, è ben trovato,” the Italians say: “If it’s not true, it’s well-conceived.” That would certainly be the case for this unprovable anecdote: well-conceived inasmuch as Mehmed was a warrior, and had some experience of bloodshed, while Bellini, as a Renaissance painter, would have recognized anatomical verisimilitude as something worth striving for.

Decapitation played a part in the Venetian perspective on Mehmed dating back to the siege of Constantinople in 1453, for the Venetian envoy, or bailo, was beheaded after the Turks took the city. According to the Venetian account of Nicolo Barbaro, “while the massacre went on in the city, everyone was killed; but after that time they were all taken prisoner. Our bailo, Girolamo Minotto, had his head cut off by order of the Sultan; and this was the end of the capture of Constantinople.” The Turkish pursuit of decapitation was also reported as an aspect of the Ottoman invasion of southern Italy at Otranto in 1480-1481, the last year of Mehmed’s reign.

Karin-edis Barzman has taken the familiar story of Mehmed and Bellini and, very originally, has made it into the starting point for an exploration of the broader significance of decapitation in the early modern Venetian-Ottoman encounter, as considered in her new book The Limits of Loyalty: Early Modern Venice, Dalmatia, and the Representation of Difference. Barzman explores the ways that both literary and artistic images of beheading served to dramatize for Venetians especially—and for Christian Europeans more generally—the supposed cruelty and barbarism of the Ottoman Turks. At the same time, however, decapitation persisted as a criminal penalty in Venice itself, and more widely in Europe, as an act of justice, and so the boundary of cultural separation was not absolute. Indeed, “porous” boundaries form a part of the framework for Barzman’s study— with reference to Benedict Anderson’s formulation of the unclearly delineated borders of early modern empires—and she focuses particularly on Venetian imperial identity, “venezianità as measured against the perceived alterity of the Ottoman Turk.” (4)

The Venetian republic and the Ottoman Empire, while frequently at war during the early modern centuries, also enjoyed extended periods of closely coordinated diplomatic and commercial relations. Barzman cites the important research that emerged from the Central European University’s “Triplex Confinium” project of the 1990s, considering the ways in which the highly militarized Ottoman-Habsburg-Venetian triple border fostered not only hostilities, but also unexpected correspondences, resemblances, and exchanges. Beginning with the story of Bellini and Mehmed in her first chapter, Barzman’s final chapter follows the history of decapitation into the Venetian ranks, as undertaken by the irregular troops of Morlacchi, the nomadic South Slavs of the border region, who shifted from Otoman to Venetian sovereignty and service, and could not be restrained from beheading the Turkish enemy soldiers encountered in battle.

Bellini was in Istanbul in 1479 and 1480, but the story of his anatomy lesson with the sultan was not published until 1648 with Carlo Ridolfi’s art history of the lives of Venetian painters. Barzman nicely observes that Ridolfi’s publication coincided with the beginning of the Venetian-Ottoman war over Crete, which would ultimately conclude with the Turkish conquest of Venetian Crete in 1669. The anecdote of Mehmed’s sanguinary demonstration thus emerged at a moment of military engagement when Ottoman bloodshed would have carried a contemporary significance. The Cretan war in the Mediterranean was accompanied by Ottoman-Venetian warfare on the Bosnian-Dalmatia border in southeastern Europe, and an Ottoman assault on the Venetian fortress at Novigrad, near Zadar, in 1646 was supposed to have resulted in the mass decapitation of Venetian soldiers—the news reaching Venice just as Ridolfi would have been writing about Bellini in Istanbul. While contemporary Venetians were anxiously convinced of the Ottoman appetite for beheadings, Barzman, correspondingly, observes “an appetite in Venice for narratives of decapitation.” (50) It was also in 1648, the year of Ridolfi’s art history, that Alessandro Vernino published in Venice a history of the contemporary Venetian war against the Turks in Dalmatia.

Barzman thus pays keen chronological attention to the overlapping of events and publications in the 1640s, and in her final chapter on the Morlacchi she returns to 1648, the year of Ridolfi and Vernino, which was also the year that Venice deployed Morlacchi troops against the Ottoman fortress at Klis in Dalmatia, near Split. The Venetian Provveditore Generale, the governor of Dalmatia, Leonardo Foscolo, reported on the lack of discipline of the Morlacchi in battle, their “reckless courage (temerario corraggio) when massively outnumbered,” but also observed their extreme violence on the battlefield against the Turks “taking the heads of nine who had been left for dead on the battlefield.” (245-46) At this point, the decapitators were fighting on the Venetian side, though their bloodthirstiness was partly explained by the fact that the Morlacchi were formerly in Turkish military service. The image plates include a beautiful series of pen and ink drawings, from the Biblioteca Marciana, representing the assault on Klis, with little Morlacchi figures engaged in the maneuver, and in one image actually decapitating the Turkish enemy. In a sixteenth-century Latin humanist source the Morlacchi were characterized as “bestial rather than human in aspect” (ferinum potius quam humanum aspectum) (236), while a seventeenth-century Italian source described them having “cut to pieces” (tagliato a pezzi) a Bosnian Ottoman official and his family, then “removing the heart” (levandoli il cuore)—as if practicing a sort of Aztec ritual barbarism.

In the eighteenth century, the Venetian Provveditori Generali in Dalmatia would become deeply preoccupied with exercising administrative “discipline” over the Morlacchi residents of the province, while in Foscolo’s seventeenth-century account of the taking of Klis the military management of the Morlacchi was already a major issue. In a dispatch to the Venetian Senate, he described his efforts “to urge the Morlacchi to bring in a greater number of slaves”—that is, to take Turkish prisoners as galley slaves rather than Turkish heads as trophies—but “they would prefer to cut off their heads to vindicate themselves rather than makes prisoners of them to a useful [end].” (251) Barzman’s study thus illuminates a certain economy of decapitation in which the practice of ostentatious violence—“the spectacle of horror,” according to another Venetian report by Girolamo Brusoni—was supposed to be tempered by practical considerations. Brusoni suggested a different economy of decapitation from the Ottoman perspective, when an officer had his captured slaves, probably Morlacchi, beheaded: “He presented the Pasha [of Ottoman Bosnia] with six banners and forty heads. The Pasha welcomed him with gestures of courtesy, giving him 6 Reali per banner and five for each head.” (61) Thus, the Ottoman-Venetian encounter, as mediated by the proverbially violent Morlacchi, involved divergent valuations of live slaves and severed heads, with those values actually measurable in cash equivalents. In 1683, at the time of the war of the Holy League that defeated the Ottoman siege of Vienna, there was a massacre of Ottoman subjects carried out by the Morlacchi on the borders of Venetian Dalmatia, and in this case the Ottoman government was reported to have requested that Venice deliver a comparable number of Venetian subjects for what Barzman characterizes as “compensatory beheading” (61) — the proposed equivalency again reflecting a sort of economic balance of violence. The Venetians rejected the proposal.

While decapitation appeared in Venice as a mark of Ottoman barbarism and Morlacchi primitivism—indeed an emblem of inhumanity in both cases—Barzman demonstrates that there also existed a positive Venetian valuation of decapitation as focalized in the figure of the biblical Hebrew Judith who cut off the head of the enemy general Holofernes, and this act of decapitation was frequently represented in Italian Renaissance and Baroque art. In these works—including the most famous example by Caravaggio— the violence of Judith was celebrated as an act of justice, and in Venetian culture, including Titian’s treatment of the subject, the figure of Judith was assimilated to the allegorical female figure of Justice, while the biblical Holofernes was associated with the contemporary Ottoman enemy. The most clear-cut instance of this association was not in art, but in music, when Antonio Vivaldi composed his oratorio Juditha triumphans at the time of the seventh Ottoman-Venetian war of 1714-1718. One fascinating image included in Barzman’s plates is a woodcut—German not Venetian—from the 1570s, the decade of the Christian naval victory over the Turks at Lepanto, showing a Turkish pasha splendidly dressed in an ornate robe and a plumed turban, standing alongside a miniature image of his own severed head, also wearing the same plumed turban. (Plate 36) In this image the proud pasha appears not in the least barbaric and stands beside his severed head with the utmost human dignity.

Barzman’s striking focus on the imagery and signification of beheading helps to bring together her chapters which read as somewhat loosely related articles about different aspects of the Venetian-Ottoman encounter. The chapter on images of Judith, for instance, is followed by another on the Venetian publications of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, the epic Renaissance poem about the medieval crusades, which, Barzman suggests, became in Venice a kind of commentary on the contemporary struggle against the Ottomans, with illustrations that put the medieval Muslims in Ottoman costumes. The general title of Barzman’s book The Limits of Identity gives only a very vague idea of what the book is about, while the subtitle, invoking Dalmatia, also fits oddly, for Dalmatia is important only in the first and last chapters. Strangely, the Ottoman Turks are not even mentioned in the title, though they are fundamental to every part of the study. At the same time, the book is oddly theorized, with a puzzling proposal of the relevance of Roland Barthes’ S/Z (“the nothingness of the castrated body, the falsity of a counterfeit sex’) for explicating the subject (11), and Barzman also argues for the importance of “trauma” for understanding Venetian-Ottoman relations: “We might say that the Morlacchis’ habitual recourse to decapitation signaled an inability to ‘work through’ the trauma they had experienced while Ottoman subjects.”(252) While these reflections will not necessarily engage all readers, the book is truly original in its cultural insights into the expression and representation of extreme violence—as summed up in the act of decapitation—in the long historical encounter between Venice and the Ottoman empire.

Historians will read this work with great interest for its relevance to the border studies that were opened up in the 1990s with Wendy Bracewell’s now classic work The Uskoks of Senj, and also the “Triplex Confinium” project that originated at the Central European University in Budapest. The range of studies on Venice and the Ottomans over the last generation has proceeded from Lucette Valensi’s celebrated essay on The Birth of the Despot: Venice and the Sublime Porte, dating back to the 1980s, and including the more recent work of Eric Dursteler on Venetians in Constantinople. The great Ottoman historian Leslie Peirce has just published a brilliant new biography of Roxelana or Hürrem Sultan—Empress of the East—the favorite of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, and Barzman offers a wonderful pictorial complement, showing how a sixteenth-century woodcut “Favorita del Turco” featured a tall cap associated with Roxelana (Figure 39), also used in the Titian portrait “La Sultana Rossa” (Plate 42), and finally transposed as Clorinda’s headdress for a seventeenth-century illustrated addition of Tasso (Figure 35). With a sensitive eye for visual detail, Barzman complicates our understanding of the graphic aspects—from headpieces to beheadings—of the early modern Ottoman-Venetian encounter.

Reviewed by Larry Wolff, New York University

The Limits of Identity: Early Modern Venice, Dalmatia, and the Representation of Difference

By Karen-edis Barzman

Publisher: Brill

Hardcover / 315 pages / 2017

ISBN: 978-9004331501

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on July, 2 2018.